In 2017, Hennie Thomson checked herself into a hospital for six weeks of in-patient treatment for anorexia nervosa. She was compulsively over-exercising — running, spinning or cross-training three to four hours daily. She ate only one meal each day of the same four foods. And she felt she had hit the bottom of a deep depression.

In the hospital, she would be observed around the clock and her meals would be communal and strictly monitored by health-care staff. She could do no exercise, and would even have an escort to the bathroom.

“It was very overwhelming; I hated losing control and I cried for the first couple of weeks,” recalls Thomson, 27, who works as a portfolio manager in scientific publishing in Oxford, UK. “But I knew I needed it if I was going to ever feel better and recover.”

Thomson’s regimen might appear drastic, but eating disorders, which affect millions of people globally, are some of the most stubborn mental health disorders to treat. Anorexia, in particular, can be deadly. Thomson’s disorder followed a familiar pattern: As is common, it developed when she was an adolescent, and though she had some successes with treatments during high school and university, she suffered a relapse after a major life change — in her case, a move to a new job with unpredictable routines.

She experienced the shame and denial familiar to people with eating disorders, whose biological and psychological urges conspire against them, stopping many from ever seeking treatment at all. Those who do reach out for help have limited and imperfect options: Only psychological interventions are available, and these specialized therapy treatments work only in about half of patients who have access to them.

But in recent years, scientists have made inroads. They know more about which psychological treatments work best, and are hoping to devise new types of therapies by exploring how genetic or neurological causes might underlie some of the disorders.

Meanwhile, an unexpected silver lining to the Covid-19 pandemic was that pivoting to delivering treatments remotely through video calls was largely successful, reports find. This raises the hope that effective telehealth might broaden therapy access to more people, especially those in rural areas.

What is an eating disorder?

While it’s a myth that eating disorders affect only thin, affluent, young white women, it is true that women are diagnosed at numbers much higher than men. Low rates of reporting and treatment make it difficult to know how many people actually are affected, but estimates suggest 13 percent of women and 3 percent of men, representing half a billion women and more than a hundred million men.

The three most common eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. Anorexia is characterized by severely restricted eating and/or over-exercising. It also has the highest mortality rate — up to 20 percent if left untreated — of any psychiatric illness.

Bulimia shows a pattern of binge eating followed by compensating behaviors, such as vomiting or using laxatives. And binge-eating disorder is defined as recurrent episodes of overeating without compensating behaviors. These three disorders share similar psychological patterns — such as a preoccupation with weight and shape — that lead to a loss of control around eating. Although they have different behaviors and physical symptoms, they are treated in therapy in similar ways.

The causes of eating disorders are complex and are usually ascribed to a blend of biological, psychological and cultural influences unique to each individual. As such, general risk factors are hard to nail down. Studies that followed thousands of people before and during the development of an eating disorder while tracking dozens of potential risk factors found that the only consistent, universal risk factor for people with bulimia was a history of dieting. For anorexia, the only clear risk factor was being already thin, with a low body mass index — a measurement of body fat relative to height and weight. (Scientists do not yet know whether this is a sign of sub-clinical anorexia or a factor that predisposes people to developing the disorder.) The studies did not find any consistent risk factors for binge-eating disorder.

More generally, people with anorexia tend to have high levels of anxiety, strong perfectionistic tendencies and commonly have experienced trauma, says anorexia researcher Andrea Phillipou of Swinburne University of Technology in Australia. Therapists report that other common risk factors include having close relatives with an eating disorder and going through stressful major life events, such as going to high school or college, changing jobs or menopause, says Elizabeth Wassenaar, regional medical director for the Eating Recovery Center in Denver.

Only an estimated 25 percent of people with an eating disorder in the US receive treatment. There are many reasons at play, says Cara Bohon, a psychologist at Stanford University School of Medicine. “There is a lot of denial, guilt, shame and hiding of the problem. And there is still stigma around getting treatment.”

Disorders also often go undiagnosed in men or non-white people due to bias of health-care providers who think these disorders arise only in white women. Access to the kind of specialized therapies that can help some sufferers is limited and expensive. Waits to see therapists can be long in the US and other countries, and eating disorder specific therapy is not available at all in many others. During the pandemic, treatment delays often stretched into many months or, in some places, as long as a year-and-a-half. That’s a huge concern for an illness in which earlier treatment is associated with a greater chance of recovery.

How cognitive behavioral therapy helps

In contrast to other mental health disorders, eating disorders have no drug treatments, only psychological therapies and, for anorexia, medical interventions to re-nourish the body. Since 2003, many therapists have adopted the idea that although these three eating disorders manifest in different ways, the same psychological processes contribute to all three. Therefore, therapies designed to block harmful thought patterns should work for all of them.

Controlled studies have shown cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to be the most effective treatment for adults with bulimia and binge-eating disorder. For anorexia, the picture is more complicated and fewer controlled studies have been done, but in those studies, CBT was equally effective as other therapies. Even so, CBT has long-lasting success only for an estimated 30 percent to 60 percent of people, depending on their exact disorder and its severity.

Other forms of psychotherapy, also known as “talk therapy” — such as interpersonal therapy and psychodynamic therapy, which both focus on relationships — can also be effective at treating eating disorders. And for adolescents with anorexia, family-based therapy is the gold standard.

Therapists say that many people struggling with any one of these three disorders find relief in the rigor of CBT, in which therapists literally follow a manual’s protocol. At the same time, CBT is highly collaborative between the therapist and patient, who together come up with “homework assignments” meant to get the person to recognize and interrupt the daily thoughts and behaviors that drive their eating disorder.

“That helps them to see that it’s really them making changes, rather than the therapist prescribing changes,” says psychiatrist Stewart Agras of Stanford University. For example, the person might be asked to monitor all events around eating — not just what they ate and when, but the location, whether it was with others, and the emotions before, during and after. Another assignment might be to take notice of what activities triggered body-checking in mirrors or negative body image thoughts.

One of the core signatures of eating disorders is a constant assessment of eating, body shape and weight. “The person feels in control when dieting and this is why they continue these behaviors despite the damaging consequences to their health and relationships,” says Riccardo Dalle Grave, director of eating and weight disorders at the Villa Garda Hospital in Garda, Italy.

Because CBT attacks head-on the thoughts and behaviors common to eating disorders, Agras says, some people feel they are making progress right away.

Denise Detrick, a psychotherapist who specializes in eating disorders in her private practice in Boulder, Colorado, says she finds it most helpful to use CBT in conjunction with other psychotherapies that are geared toward getting at the root causes of an individual’s eating disorder. She likens CBT to a cast for a treating a broken arm: “CBT helps combat the negative thoughts, and you need that cast, but you’re going to keep breaking your arm over and over again if we don’t understand the cause.”

New insights into the biology of eating disorders

But for all of the evidence behind CBT, it leads to recovery in only about 60 percent of those treated for binge-eating disorder and 40 percent of those treated for bulimia. For anorexia, all treatment methods combined result in recovery for just 20 percent to 30 percent of people treated. That’s clearly not good enough, says Cynthia Bulik, who is looking for more effective treatment possibilities by studying the genetics that underlie eating disorders.

“There is a large genetic component to eating disorders, especially in anorexia and bulimia, where about 50 to 60 percent of the risk of developing the disorder is due to genetic factors,” says Bulik, a clinical psychologist and founding director of the Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. In binge-eating disorder, that genetic influence is around 45 percent, she says.

In other words, inherited gene variants — likely many hundreds — influence about half of the risk a person has of developing an eating disorder. Not everyone with a particular suite of gene variants will develop one, just as not everyone with a genetic predisposition will develop cancer. The other half of risk comes from environmental, cultural or psychological factors.

There are clear biological and metabolic mechanisms at play. “When most of us are in a negative energy balance — that is, spending more energy than we’re taking in — we get hungry and hangry,” Bulik says. “But people with anorexia find a negative energy balance to be calming. They feel less anxious when they are starving.”

Bulik and others are conducting what are known as genome-wide association studies to catalog the genes that are different in people with eating disorders. The scientists are part of the Eating Disorders Genetic Initiative, which aims to gather genetic and environmental data from 100,000 people with the three common eating disorders from 10 countries in Europe, North America, Asia and Oceania.

The goal is to identify the most common and most influential gene variations, and drill down on what those genes control in the body. That might open the door to discovering medical treatments that could, for example, adjust the affected brain signals in someone with anorexia back to “hungry” when energy runs low.

Phillipou takes another biological approach to eating disorders at her lab at Swinburne University. Her research, on anorexia, explores the connections between specific eye movements and the brain circuits that control them. Interestingly, these eye movements, called square wave jerks, show up much more frequently not only in people in treatment for anorexia and those who have recovered from it, but also in their sisters who have never had an eating disorder.

The area of the brain that controls these eye movements, called the superior colliculus, is involved in integrating information from multiple senses. Phillipou’s group has found that people with anorexia have less connectivity between their superior colliculus and other brain regions. “Potentially, this could mean that people with anorexia are not integrating what they are seeing and feeling about their own bodies properly,” she says.

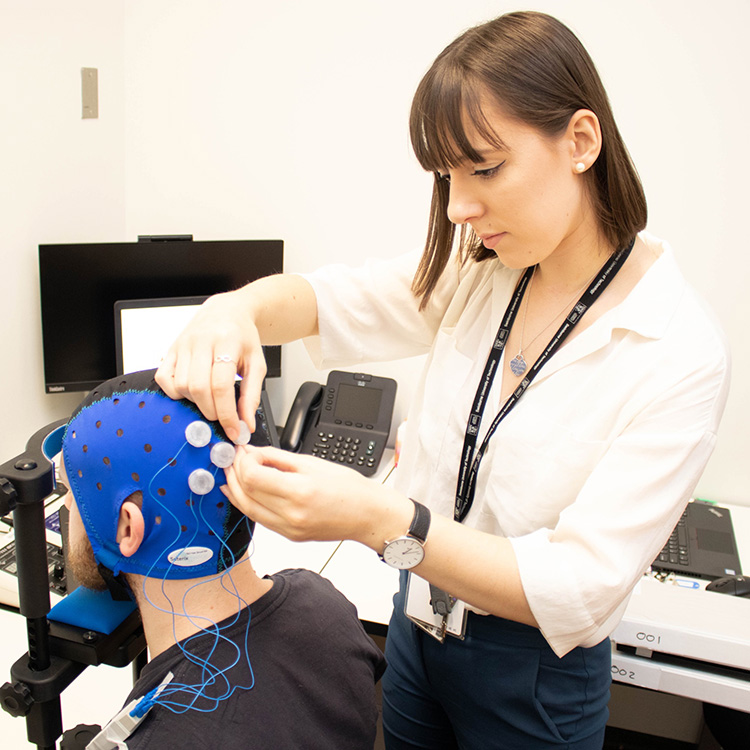

Research assistant Stephanie Miles adjusts a volunteer’s electric current stimulation cap for a pilot study of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) at the Anorexia Nervosa Research Group at Swinburne University in Australia.

CREDIT: COURTESY OF ANDREA PHILLIPOU

Her group is testing whether small electric currents delivered through the skull to one of the areas contacted by the superior colliculus, the inferior parietal lobe, can improve the symptoms of anorexia by encouraging more active firing of neurons. (Similar treatments targeting different brain areas are approved in the US for treating depression.)

Another avenue for treating symptoms of anorexia that researchers are exploring is using psilocybin, the psychedelic ingredient found in mushrooms. Psilocybin acts on the same receptors in the brain as the neurotransmitter serotonin, a key molecule for regulating mood and feelings of wellbeing. People with anorexia have less serotonin signaling in certain brain regions compared with people without anorexia.

Dealing with an eating disorder during the pandemic

The pandemic has thrown a dramatic spotlight on just how acute the need for effective treatments has become. “Eating disorders don’t get better in isolation, they get worse,” says Wassenaar of Denver’s Eating Recovery Center.

The loss of control over certain aspects of life that many have felt during the pandemic has been particularly difficult for people with eating disorders, experts say. At Denver Health’s ACUTE Center for Eating Disorders and Severe Malnutrition, a national intensive care unit, the percentage of new, severely ill patients arriving by air ambulance jumped nearly four-fold in April to June 2020 compared with pre-pandemic levels.

In surveys about the pandemic, both people with and without eating disorders reported an uptick in disordered eating, with such behaviors as restricting certain foods, dieting, binging or purging, and increased depression and anxiety. These trends held true for everyone but were stronger for people with eating disorders. And early in the pandemic, more people with eating disorders said that they were worried or very worried about the pandemic’s effects on their mental health versus their physical health (76 percent versus 45 percent).

“That really jumped out at me,” says Bulik, who ran one of the surveys with colleagues from the Netherlands. “All of a sudden, social supports and structure disappeared from our lives.”

The pandemic has also been terrible for adolescents coping with an eating disorder, Wassenaar says. In Michigan, the numbers of adolescents admitted to a children’s hospital for eating disorders was more than double in the year from April 2020 to March 2021 compared with the average of the previous three years. During adolescence, children need to venture out from the home, connect with friends and gain some sense of control and invincibility, Wassenaar says, but the pandemic took away many of those activities. “Teens are experiencing the world as an unsafe place.”

Lockdowns also forced nearly all therapy sessions to switch to video calls. But this shift may help those who previously were unable to get therapy from a practitioner experienced in treating eating disorders. Even before the pandemic, studies had shown telehealth CBT to be equally effective as face-to-face CBT for a variety of mental illnesses, including bulimia. Many people appreciate the convenience of doing sessions from home. The virtual sessions also cut down on driving time and missed appointments and, therapists hope, could help to expand access to rural areas.

“I see this kind of therapy becoming a norm,” says Agras, who has studied eating disorders for more than 60 years.

Creative coping during Covid

For those like Thomson going through recovery in isolation, creative coping mechanisms become important, experts say. That’s because “getting out of your head and away from the tail-chasing mental thoughts becomes much harder,” says Bulik.

Therapists have had to suggest ways to create structure out of nothing, using sticky-note reminders, doing different activities in different rooms, and not working in or near the kitchen. For example, to help her stick to her weekly meal plans, Thomson packs herself a lunchbox and stores it in the fridge each day even though she is still working from home.

At some points during the pandemic, she also forced herself to pair up with another household, so that she would have to eat dinner with others twice a week. “The friend was a really big foodie who loves to cook, and I had to be okay with that,” Thomson says. Although people with eating disorders often don’t like eating in front of others, experts say that they find the accountability of it and the distracting conversation helpful.

Eric Dorsa, who is also in recovery for anorexia, found ways to build connections and distractions back into their pandemic routines. Dorsa, a 33-year-old eating-disorder and mental health advocate in New York City, rebuilt social connections via FaceTime conversations with friends and runs a virtual support group for LGBTQ+ people in eating-disorder recovery. They also hosted a pandemic-coping miniseries on Facebook Live for the recovery community, called “Quaran-Tea.”

“I had to get a therapist for the first time in six years,” via telehealth, Dorsa says. With the uptick in food fears and news stories of people hoarding food from grocery stores, all of their insecurities around food came flooding back. “I knew I needed help.”

Given that recovery, even with the best therapy, is far from guaranteed and science cannot yet predict who is most at risk for relapse, Bulik and other therapists warn people to keep an eye out for likely triggers — a big move, work travel or schedule changes, loss of a loved one or emotional stress.

Bulik also sees another easy way to help more people with eating disorders: “When physicians take a new patient’s history, there’s no box to check for having a past eating disorder. There should be.”

If you or someone you know is struggling with an eating disorder, the Eating Disorders Review website includes resources, helplines and hotlines.

For help with specific disorders, more information may be found through these US organizations:

National Eating Disorders Association Helpline 1-800-931-2237 (M-Th, 11 am to 9 pm, Eastern US Time; F, 11 am to 5 pm, ET)

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders Helpline 630-577-1330 (M-F, 9 am to 5 pm, Central US Time)