For some cities, problems with flooding began at the beginning.

When European settlers arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, in the late 17th century, about half of the peninsula there was salt marsh or creek. So for generations, Charlestonians used low places as trash dumps and added dirt or fill to wetlands and waterways to create new land.

But water, which buffets the city’s downtown on three sides, is now reclaiming many of those same places during high tides and storm surges. More and more often, the city must close flooded districts to traffic. Stubborn motorists still try to drive through hip-deep floods, stalling engines and leaving vehicles stranded.

When my wife and I moved to Charleston 33 years ago, floods happened several times a year. Since 2014, flooding has occurred more than 40 times each year, with a spike of 89 times in 2019, overwhelming drainage systems. Broadcasters announce high tides and heavy rains like road accident reports. In November 2021, one of the peninsula’s largest and oldest employers, Roper St. Francis Healthcare, revealed a $500 million plan to move its flagship hospital from downtown, citing flooding costs. City officials say that the price tag to address flooding and sea level rise in Charleston is $3 billion.

Flooding has become an existential crisis for many US coastal cities as climate change drives global average sea levels higher, strengthens tropical cyclones and other storms, and creates more dangerous surges. The question today is not whether coastal cities will build stronger flood protections — they will — but instead where, when and what kind, and how to pay for them.

Coastal urban centers won’t close up shop and move inland. Large-scale retreat is not a feasible political or economic option — yet. Instead, Charleston and at least seven other Gulf and East Coast urbanized regions — from Galveston, Texas, to Boston — are partnering with the US Army Corps of Engineers, the federal agency responsible for storm surge protection, to explore or plan massive seawalls and other defensive structures.

Politicians have always preferred “gray” infrastructure for controlling water: seawalls, levees and dikes, sewers and stormwater pipes, water pumps, and other hardened systems often involving concrete or steel. Gray systems are big, visible and promoted as highly reliable, though some have notoriously failed, including New Orleans’s defenses during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

But even seawall proponents acknowledge that they are expensive and require a decade or more to plan and build. Giant walls can block views and harm habitat quality and biodiversity. They can channel destructive flooding to unprotected sites in the same bay or estuary, as a 2021 study of San Francisco Bay showed.

Meanwhile, evidence is accruing that natural systems such as salt marshes, oyster reefs and mangroves can often function as effective shoreline buffers, blunting waves and other impacts of coastal storms. Human-engineered designs, such as artificial wetlands and parks, can store stormwater and help to filter and cleanse it.

And so, as they forge their plans, governments and other stakeholders are turning to traditional remedies — the seawalls, dikes, levees and other hardened protections — but increasingly, are also considering complementary green or nature-based techniques. The Corps, which has historically resisted certain green flood protection options as insufficiently tested for urban storm protection, has also begun embracing them in some locations.

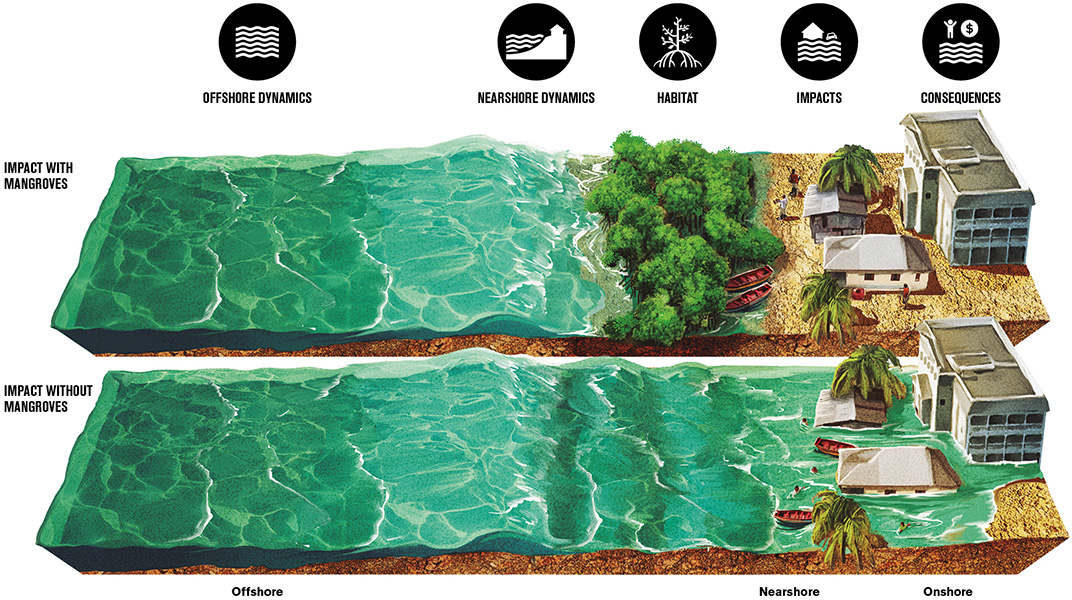

Mangroves can protect structures behind them by reducing the height of a storm surge onto land. The plants’ roots also stabilize sediments, lessening erosion. Studies have confirmed that economic losses from storms hitting the US coast have been reduced by mangroves — except in spots where structures are built between mangroves and the shore (in those cases, property damage increases).

CREDIT: M.W. BECK ET AL / WORLD BANK 2019

A major influence in this sea change has been the Netherlands, a lowland country with centuries of experience in reclaiming land and holding back the sea. As nations confront rising sea levels, the Dutch have emerged as global leaders in managing water by integrating engineered and natural systems. A key part of their current strategy is to work with — not just fight — rising tides and increased flooding from coastal rivers.

Recent activity stands to feed a US shift toward green flood protection. In 2020, Congress directed the Corps to consider nature-based systems in flood protection planning, and in January 2021, President Biden issued an executive order aimed at tackling the climate crisis and encouraging green solutions.

Meanwhile, there’s a surge of money pegged for flood control: In November 2021, Biden signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which provides $2.55 billion to the Corps to protect coasts and other shorelines and reduce flood risks and damage.

It’s not a matter of one or the other — green or gray — for coastal protection, says Todd Bridges, who heads the Corps’ Engineering with Nature initiative; in 2021, it published a 1,000-page atlas of international guidelines for nature-based systems, developed in partnership with the Netherlands and other countries. “In the majority of cases, there are going to be opportunities to find combinations,” he says. “And in some cases, the constraints will be that it’ll lean more towards one end of the spectrum than the other.”

A surge of concerns

Coastal cities are increasingly anxious to fix flooding because they are running out of time. Since 1920, the sea level has risen 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 centimeters) around the continental US.

This process is accelerating: More than one-third of that rise has occurred over just the last 25 years, according to a February 2022 report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Over the next 30 years, the US will experience another 10 to 12 inches of sea level rise, reaching up to 14 inches on the East Coast and 18 inches on the Gulf Coast because of sinking land and other factors.

In the 1970s, the city of Charleston experienced an average of two days of tidal flooding per year. By midcentury, the city says it expects 180 days of tidal flooding.

Many coastal cities were built on flat, low deltas or river floodplains. Water drains slowly off their streets and sometimes must be pumped out, and yesterday’s infrastructure isn’t up to the job. More intense “rain bombs” — extreme precipitation events — driven by climate change are filling up stormwater drainage outlets as sea levels and tides rise. Stormwater can’t escape street drainage, so it backs up, flooding streets. Rising groundwater levels, meanwhile, bubble up through soils, inundating yards and damaging home foundations and infrastructure.

This warrants a shift from just trying to keep water out, as the people of the Netherlands learned decades ago.

Wetlands like this salt marsh in Barnegat Bay, New Jersey, help to protect communities against flooding during storms. Like mangroves, the ecosystems reduce wave energy by providing resistance to the flow of water.

CREDIT: ISTOCK.COM / SONDRAP

Over centuries, the Dutch drained and filled marshes to create new dry land. Then, in 1953, a storm surge flooded the Netherlands, killing more than 1,800 people, destroying 4,300 homes and damaging 43,000 more. In response, the Dutch bolstered their flood protection with three new locks, six dams and five massive storm surge barriers.

After floods in 1993 and 1995, the Netherlands adapted again, creating a “Room for the River” program. It bought out flood-prone homes and farms. It opened up the floodplain and planted willow trees and reeds as natural wave-reduction systems, and then let floods in. The restored floodplain became a safety valve, temporarily holding and filtering water.

Today, the Dutch do not rely on one type of protection but on many different green and gray methods in redundant, complementary layers. They built hard barriers and renourished sandy shorelines to blunt storm waves from the North Sea. Behind the first line of protection, they restored oyster reefs, salt marshes and freshwater wetlands to buffer or store floodwaters, and improved dikes and other hardened systems as further protective barriers.

They also added new water management systems inside their cities: green roofs and “water plazas” that provide temporary water storage and thus buffer communities against flooding. It’s a much more comprehensive approach, says Dale Morris, Charleston’s chief resilience officer, who worked for many years in the Netherlands Embassy in Washington, DC.

Morris and New Orleans architect and urban designer David Waggonner were largely responsible for introducing Dutch water-management principles to local policymakers and community leaders in the United States. After Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005, they cofounded the Dutch Dialogues process, which offers water-planning workshops to flood-prone American cities. “We have brought the Dutch approach and anchored it in the American landscape,” says Morris.

The discussions are having an influence.

In devising a proposal to protect Greater New Orleans against future flooding, planners turned to the experience of the Dutch. A key principle is to design in a way that can manage a temporary influx of water rather than try to keep the water out altogether.

CREDIT: GREATER NEW ORLEANS URBAN WATER PLAN, WAGGONNER & BALL ARCHITECTURE / ENVIRONMENT

In 2008, a Dutch Dialogues workshop in New Orleans brought together urban designers, planners, engineers and policymakers to find localized solutions to the flooding there. At the time, Morris says, there was a strong push for the federal government to rebuild and strengthen the existing perimeter protection system — a mix of gray and green elements that were aimed at keeping water out of the city.

But the Dutch Dialogues team wanted resilience inside the city as well. The resulting Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, published in 2013, shows how New Orleans should integrate green and gray infrastructure inside of the city’s flood-protection perimeter. The plan, which is not mandated by any government, has influenced local and state flood-protection policies. But it calls for additional local taxes to strengthen levees further and improve water management inside of them — and that’s a difficult political challenge, Waggoner says.

The Dutch Dialogues also inspired a resilient design effort after Superstorm Sandy blasted the East Coast in 2012, causing more than $60 billion in reported damage. In 2012, the Obama administration authorized a rebuilding task force, which launched the Rebuild by Design competition to support innovative flood-proofing plans, providing $930 million in federal funding for the winners.

Among those winners was the city of Hoboken, New Jersey. Sandy caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage to private property and the transit system, leaving waist-deep water across much of the low-lying city for days because of drainage problems. The city is building a five-acre Northwest Resiliency Park with lowland gardens and trees to soak up as much as one million gallons of urban stormwater during flood events. A below-ground tank with a filtration system will store another one million gallons.

A family walks through the flooded streets of Hoboken, New Jersey, in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, which wrought devastation in 2012.

CREDIT: REUTERS / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

“These are the sorts of things that we need to include more of — more open spaces, even within cities, where the wetlands serve as a sponge,” says Michael Beck, a marine scientist with the University of California, Santa Cruz, who coauthored an overview of returning nature to oceans and coasts in the 2021 Annual Review of Marine Science. “It’s not just seawater coming in; it’s rainwater coming to meet it at the same time” — overwhelming urban stormwater systems and causing flooding.

It’s politically and economically challenging, of course, for cities to take land parcels worth multiple millions of dollars off local tax rolls and convert them to green flood control. But urban leaders will be driven more and more to act, predicts Beck. “As the scope of the problem increases, you’re going to also see the number of options increasing as well,” he says.

Preserving wetland benefits

Research is amassing in support of saving existing green flood protections. In a 2020 study, for example, researchers assessed property damage caused by tropical storms and hurricanes hitting the US Atlantic and Gulf coasts between 1996 and 2016. They found that counties with fewer wetland acres experienced significantly more damage. In Florida, the researchers calculated that wetland losses in 19 coastal counties over that that 20 years contributed $430 million in additional property damage from Hurricane Irma in 2017.

Some of the research adapts the same computer models that the insurance industry uses to assess the drivers of disaster costs. This allows researchers to quantify the economic value of wetlands and other natural coastal systems in storm defense, providing cost-benefit fodder for states and localities in their flood mitigation planning.

In one such study, Beck and colleagues modeled storm surges with and without coastal wetlands in 12 coastal states along the northeastern US. They estimated that the wetlands prevented $625 million in flood-damage costs overall during Hurricane Sandy. The report dug more deeply into a local area and reported that the presence of coastal marshes in a bay in Ocean County, New Jersey, reduced flood damage by an average of 16 percent annually.

Wetlands do not have to be right next to communities to help protect them. In this example, scientists estimated that inland Hamilton Township, New Jersey, had significant reductions in property damage during 2012’s Hurricane Sandy due to the wave-taming effect of downstream wetlands, even though the township has very few wetlands itself. (In the chart, colors indicate the percentage of savings (positive percentages) or losses (negative percentages) due to wetlands.)

Using similar methods, Beck and colleagues found that coastal mangroves reduced flood damage by 25.5 percent annually in Collier County, Florida. During Hurricane Irma, the scientists estimated, mangroves reduced property damage by $1.5 billion in Florida — a 25 percent saving for those counties with mangroves — and protected 626,000 Floridians from flooding.

Mangroves, dense forests that stabilize shoreline sediments and lower the height of waves during storm surges, are especially effective at storm protection. If mangroves were lost, it’s estimated that 15 million more people would be affected by flooding annually across the world.

But green is not always easy, and that goes for my hometown. Many coastal urban centers, Charleston among them, don’t have a lot of unused space in their harbors, bays and estuaries to build nature-based buffers or enhance existing ones. At the confluence of three rivers, Charleston Harbor is crowded by competing interests: recreational, national security and commercial, including a major global port with container ship traffic.

A nature-based system must be large and in a prime location to do the work of buffering storm surges: Existing coastal wetland might need to be twice its current size to have a measurable benefit as storm protection, says Bridges. Doubling the size of a wetland buffer in, say, an urban harbor would introduce more environmental and regulatory complexities and conflicts with other users, adding more time to a project’s planning phases and raising its cost, Bridges says.

In September 2021, the Corps proposed a $1.1 billion project to build a 12-foot storm surge wall along the perimeter of the Charleston peninsula. In the plan’s nod to green, the Corps would create oyster-based living shoreline structures to shield remnant salt marshes from currents and pounding waves along some of the proposed wall.

The city of Charleston recognizes that building new, large-scale green infrastructure for urban surge protection would not be realistic, says Morris. “It’s hard infrastructure that deals with a hurricane surge event,” he says. “Green infrastructure isn’t effective unless you already have miles of salt marshes or mangroves” or other natural protections.

Hard infrastructure will also be used to capture floodwaters within city walls. The city has already cobbled together tens of millions of dollars to build underground water-storage tunnels and pumps and other measures, but it will need billions more.

In 2019, the Dutch Dialogues team collaborated with Charleston officials and other partners to think more strategically about the city’s flooding challenges. The result was a recommendation that Charleston create a water plan to guide spending on flood control. “You would look at all of your flood risks,” says Morris. “That includes storm surge, tidal inundations, stormwater, groundwater levels, riverine flooding and sea level rise. You would look at all of these things together and try to make the most effective investments.”

Morris and other Charleston officials are looking at underdeveloped sites that might be converted to freshwater wetlands in park-like settings, providing recreation and internal water storage during floods — managing the water like the Netherlands’ “Room for the River,” instead of just trying to keep it out.

“We are working towards a mindset,” Morris says, “of not excluding water but respecting it.”

But some Charlestonians have tired of ever-increasing threats from floods, storms and sea level rise. It’s one of the reasons that later this summer, after 26 years in our home two blocks from Charleston harbor, my wife and I plan to sell and move inland. We hope to leave before peak hurricane season and let someone else experience the benefits — and risks — of living near the sea.