After a year and a half of lost sleep, stubborn sinus infections and one failed treatment after another, a CT scan finally revealed the source of Ashley Tacey’s misery. There, glowing gray in the image of her skull and clinging tightly to the walls of her swollen sinuses, was a layer of mucus so thick that nasal sprays, steroids and antibiotics failed to penetrate it. Tacey’s diagnosis: chronic sinusitis.

A subset of those diagnosed with chronic sinusitis are plagued by what Robert Schleimer, an immunopharmacologist at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, describes as copious quantities of “peanut butter mucin.” Though symptoms and triggers of chronic sinusitis are myriad, it’s not uncommon to see sinuses sealed completely by mucus that resembles the nutty spread in both thickness and color. “It can be one of the cardinal symptoms of the disease,” says Schleimer, “and it can be very bad.”

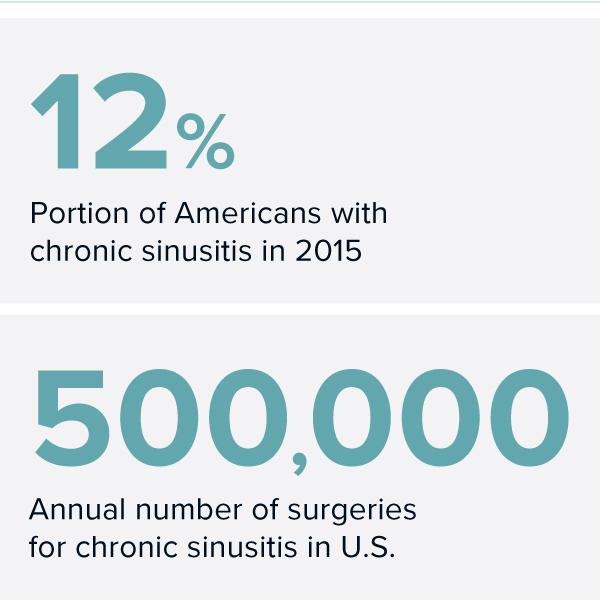

Roughly 12 percent of the adult US population was diagnosed with chronic sinusitis in 2015, and approximately $8 billion is spent annually on managing the disease. If you consider all forms of sinusitis (acute and chronic), it is the number one reason doctors prescribe antibiotics, according to Schleimer.

Despite its ubiquity, researchers are still working to understand exactly how a regular sinus infection morphs into a long-term problem. They have many unresolved questions, and even debate how and why the cavities behind our faces evolved in the first place. But research is now expanding to examine the role of genetic and immune-system players in the condition, as well as the possible contribution of our microbiome, the host of bacteria and viruses that live in and on our bodies. A number of new biological therapies now being tested in clinical trials have the potential to give physicians the first new treatment options in decades.

What is sinusitis, anyway?

Put simply, chronic sinusitis develops from perpetually inflamed sinuses. A number of inflammatory agents, from bacteria to fungi, find their way up the nose and into the membranous pockets embedded within our skulls. There they trigger immune responses that eventually run haywire. Beyond stuffed sinuses, sinusitis sufferers endure a constellation of symptoms, from disturbed sleep and fatigue to dizziness, coughing, popping ears, tooth pain and a lost sense of smell.

Most people experience acute sinusitis, in which the sinus tissues become briefly inflamed, perhaps from a cold or allergies. Usually, symptoms fade as the body’s immune players retreat. But for some, that initial infection or inflammation swells the sinus walls, sealing off all exits to the nose and throat. This traps mucus, bacteria and pus inside, which perpetuates the immune response and sinusitis symptoms. If conditions persist past three months, it’s considered chronic.

Doctors split people with the disease into two types: those with nasal polyps and those without. The symptoms of polypoid patients tend to be more persistent. The exact percentage of polypoid sufferers remains unclear, but Schleimer, writing in the 2017 Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, estimates that as many as a quarter of all chronic sinusitis sufferers have polyps.

Peer through a doctor’s rhinoscope and up the nose of someone with polypoid sinusitis, and you’ll find a pink bouquet of fleshy, balloon-like structures blocking any meaningful airflow. These polyps form from inflamed nasal tissue, and they’re unfortunately unremitting — steroids and surgical removal are often the only options, and the polyps frequently grow back. A fifth of all sinusitis surgeries are revision operations, Schleimer notes, and it’s not uncommon for those with severe nasal polyposis to have more than 10 surgeries.

Physician Tanya Laidlaw at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston says that the lion’s share of her own patients have polyps. “They really are the most miserable of my patients.”

In its most extreme forms, chronic sinusitis can move far past the inconvenience of a bad cold. “A lot of patients tell us they haven’t smelled anything in a decade, and therefore haven’t tasted anything in a decade,” Laidlaw says. “Aside from the obvious loss of quality of life and pleasure of being able to smell the flowers and taste food, there are times when this disease is actually quite dangerous.”

Laidlaw’s patients have told her that they’ve failed to notice smoke in their kitchen, that their children’s food has spoiled, and even that their house has filled with flammable gas. One patient, perpetually appearing to be sick, lost work in the food service industry, though sinusitis doesn’t necessarily imply contagion.

Dealing with sinusitis can mean toting Kleenex wherever you go — Laidlaw says that many of her patients need to blow their noses every 10 to 15 minutes. Many use rinses and hot showers to loosen the mucus. Others opt for surgery.

A behind-the-scenes tour of your face

If you peeled back skin and muscle on either side of your nose, you’d find the sinus system: a series of air pockets lined with pink, mucus-producing nasal tissue. Most people have four pairs, though some are born without any. Moving from the forehead down, the sinuses split into the frontal sinuses (just above the eyebrows), the ethmoid sinuses (a cluster of honeycomb-style pockets inside the corner of each eye), the smaller sphenoid sinuses (deeper inside the face, just behind your nose) and the maxillary sinuses (inside the cheek bones).

Beneath the pink sinus tissue are submucosal glands, which resemble clustered grapes and produce two types of secretions: serous and mucus. Serous refers to the watery snot that dribbles from eyes and nostrils on a cold morning; mucus is composed of sticky, glue-like proteins called mucin.

Working with microscopic hairs called cilia, mucus helps block harmful substances from passing into the tissue and damaging our bodies. When an irritant makes its way into the nasal passage, be it pollen or particulate matter, mucus engulfs it and cilia oscillate in unison to carry the contents back out of the nose or into the throat for digestion. Mucus contains enzymes, antibodies and antimicrobial peptides that help defend the body.

Many disease pathways can lead to sinusitis. Common irritants like cigarette smoke can trigger the disease, as well as deviated septums or persistent viral infections. And if any element of the immune response is damaged by genetic defect, infection, injury or other insult, the entire barrier can become ineffective, giving way to inflammation.

The high rate of sinus problems leads some scientists to wonder if there’s something wrong with the equipment — or ask why we have sinus cavities at all. The answer remains unclear.

“The sinuses in humans are a bit weird,” says biological anthropologist and anatomist Lauren Butaric of Des Moines University, who specializes in the structures. “There’s been a lot of debate in the literature over the centuries about what they’re for, and we’re only just starting to understand what they do. The best answer is that we have them because our ancestors had them.”

Some researchers have proposed that sinuses add resonance to our voices or that they help with balance. But there’s little evidence. One reason the sinuses so often fail us, Butaric says, is that our drainage is so poor, an effect of the inconvenient shape of our faces. Because we lack a snout, she says, our sinus system empties less effectively.

Humans versus horses: Though our sinus systems are anatomically similar, as shown in the illustration above, a horse’s elongated muzzle better allows gravity to assist in draining mucus. Human sinus cavities are more compact and easily clog when their openings swell shut from inflammation.

CREDIT: NICOLLE RAGER FULLER

In horses, cows and other long-muzzled mammals, the sinuses drain down a conveniently long face, like a waterslide powered by good old gravity. But the exit hole in our own maxillary sinuses is small, not quite as big as a fruit fly. That exit sits inconveniently toward the top of the sinus cavity where, whenever we stand erect, fluids can’t reach it. When the tissue that lines the opening swells, all exits close, trapping the mucus at the bottom of our maxillary sinuses. Centuries-old skulls can bear signs of untreated sinusitis, and Butaric has seen evidence of the condition — bubbly outgrowths or small pits on bone where nasal tissue rests — in past populations whose members spent considerable amounts of time inside huts with smoky fires.

From baby shampoo to antibodies

Given the perpetual discomfort associated with sinusitis, some patients try curious home remedies to relieve their symptoms. They squirt fruit- and honey-infused nasal rinses up their noses, or try dietary restrictions. One questionable strategy, Schleimer says, entails rinsing the nasal cavities with diluted baby shampoo, which eventually causes loss of the sense of smell. Nasal rinses should be saline, he says, as straight water can draw salt out of the sinuses and dry the sensitive tissue. Staying hydrated and putting a humidifier in the bedroom can help to thin mucus.

Because sinusitis has multiple triggers, trusted treatment options vary. Antiviral medications are effective against viral infections and, of course, anti-fungal treatments help to neutralize rarer fungal infections, though Laidlaw notes that these anti-fungal medications are relatively toxic. In allergy-driven sinusitis, she works with patients to identify the allergen and limit exposure, while also treating them with antihistamines, nasal steroids and occasionally allergy shots.

Antibiotics are commonly — and sometimes ineffectively — used to treat sinusitis. If Laidlaw can capture, culture and identify a strain of irritant bacteria in a sample of her patient’s mucus, she will prescribe antibiotics. But other physicians sometimes use the medication to treat fungal or viral infections, likely contributing to antibiotics’ common misuse. Schleimer estimates that roughly 10 percent of all antibiotics are prescribed for sinus diseases. Other studies suggest the number may be twice as high for adults.

New, promising treatments based on antibodies are on the horizon, Schleimer says, though they’re not yet approved for widespread use (and are likely to be pricey when they are). “Many of them are quite effective in reversing the symptoms, causing the nasal polyps to shrink, increasing the ability for patients to breathe air through the nose, restoring the sense of smell and reducing some of the objective measures of inflammation,” he says.

But as things stand today, sometimes surgery is the only way to bring relief. It can clear mucus buildup, remove inflamed tissue and polyps, and physically widen the tiny sinus openings — or even add new holes.

Tacey found reprieve in such surgery. She recalls tugging the last, sticky remnant from her nose after the operation: It measured 2.5 inches long. And then, she says, she breathed easily for the first time in over a year. “Everything opened back up again.”