Among food allergies, peanut allergy is one of the most severe: A minuscule amount of peanut protein may lead to anaphylactic shock and even death. Surveys show an upswing in incidence in the United States over the past two decades; a study reported in 2017 estimated that nearly 2.5 percent of US children were allergic.

All that the families of affected kids can do is avoid peanut products, and keep antihistamines or epinephrine handy in case of a reaction. Avoidance of peanuts is not necessarily easy. Kids with peanut allergies often suffer anxiety about eating — especially away from home — and fear a bad reaction.

“This passive approach is really frustrating,” says Edwin Kim, director of the Food Allergy Initiative at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, lamenting the lack of treatments to directly combat the allergy. “It stinks.”

But recent studies indicate that it may be possible to diminish allergy risk by encouraging parents to feed babies peanut products (instead of avoiding them), and to treat the allergy in older children and adults with carefully controlled micro-exposures. New treatments in the form of powder or skin patches may soon hit the market. “We’re close,” says Kim.

Here’s our update on the state of the science.

The basics

Peanut allergy is caused by antibodies that mistakenly recognize a number of proteins from peanuts as potential foreign invaders. This sets up the body to release massive amounts of the molecule histamine when it encounters peanuts a second time. An allergic reaction usually occurs within minutes and may include hives, runny nose, wheezing, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. In more severe cases, anaphylaxis sets in, leading to trouble breathing, rapid heart rate, a dip in blood pressure and other dangerous symptoms.

Foods to watch

A variety of food allergies are on the rise. It’s not certain why. One idea is the “hygiene hypothesis” — that people in the hyper-sanitized developed world don’t encounter many disease-causing agents, and their immune systems develop toward allergic responses instead. Food allergies are most common in children, who have immature digestive and immune systems.

Problem with peanuts

Peanut allergy can cause more severe reactions than other common childhood food allergies, and is less likely to be outgrown. Although good numbers are difficult to come by, scientists agree that peanut allergies are increasing.

The allergic cascade

Upon the body’s first exposure to peanut protein, via the skin or gastrointestinal tract, there is no allergic reaction. But an allergy will emerge later if, at this step, certain white blood cells target a peanut protein, identifying it as foreign. As these cells mature, they can produce allergy-linked IgE antibodies that will bind to the peanut protein at the next encounter.

In an allergic person, these anti-peanut antibodies attach to another type of immune cell, called a mast cell, that hangs out in the nose, throat, gastrointestinal tract, lungs and skin. On the second and subsequent occasions when peanut protein comes along, the mast cells recognize it and start producing histamine and other immune compounds. These chemicals cause the symptoms of a reaction, both localized ones like hives and systemic reactions such as anaphylaxis.

Epinephrine is the first line of treatment; it can reverse all symptoms within minutes. Antihistamines can also help with milder symptoms, such as localized hives, but take half an hour or longer to act. An approach called immunotherapy encourages the immune system to produce IgG antibodies, instead of IgE ones, which tamps down the allergic response.

About the allergens

Peanut protein contains 11 allergens, Ara h 1 through Ara h 11, that help to activate an inappropriate immune response. Ara h 1, 2 and 3 are the most allergenic. Seed storage proteins, the Ara proteins function as reserves for carbon and other nutrients to fuel a developing plant. Like many other food allergens, the Ara proteins make up a high proportion of peanuts, dissolve in water and resist digestion. That means they’re likely to be visible to immune cells.

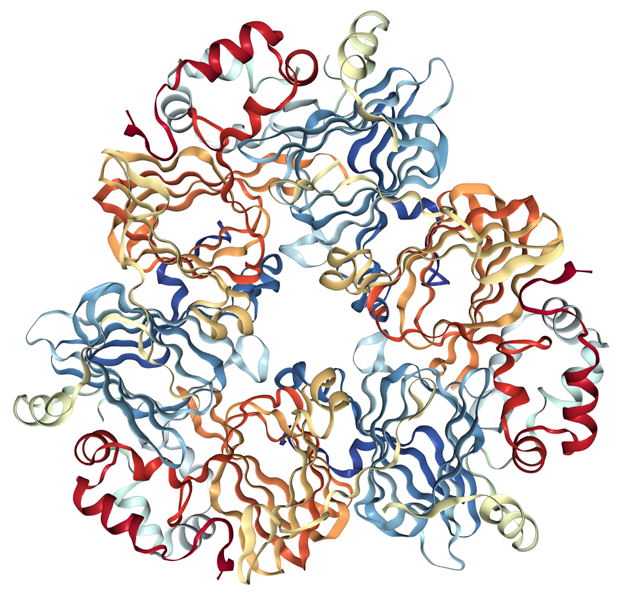

Eleven proteins in peanuts have been shown to be allergens, with three — Ara h 1 (shown), 2 and 3 — being the most potent. The Ara h proteins are plentiful in peanuts, dissolve in water and resist digestion, all factors that make them more likely to attract immune attention.

CREDIT: PROTEIN DATA BANK ID 3S7I, From M. Chruszcz ET AL/Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011

But there are things scientists don’t yet understand. Peanuts are legumes, and on the genetic level, the allergenic proteins in peanuts appear similar to proteins found in other legumes and plants. Ara h 1, the first peanut allergen identified, is quite similar to a seed storage proteinfound in peas and lentils, for example. Ara h 2 resembles a seed storage protein in legumes, almonds and sesame seeds. Despite these similarities, most people with peanut allergies do not have allergic reactions to other legumes. That suggests there’s something different about the peanut versions. And although tree nuts like walnuts and cashews are not legumes and not closely related to peanuts, about one-third of people with peanut allergy react to those nuts too.

The method of cooking peanuts can also influence the chances these proteins will be allergenic: Compared with boiling or frying, roasting peanuts seems to make the Ara h 1, 2 and 3 proteins more allergenic. Heating Ara h 2 in the presence of sugars makes it more likely to bind IgE antibodies. This may help explain why peanut allergies are more common in Western countries, where the nuts are often roasted (part of the process of making peanut butter), compared with Asian nations where raw or boiled peanuts are more common.

Staving off allergy

Scientists don’t know exactly why some people develop allergies and others don’t. Peanut allergy seems to result from a combination of genetics and the timing and route of a baby’s exposure to peanuts.

One puzzle is that some infants seem to have an allergic reaction the very first time they’re fed peanuts, before they ought to be sensitized to them. A possible explanation comes from the fact that babies with eczema — inflamed or irritated skin — are more likely to develop the allergy. Scientists suspect that sometimes the first exposure to peanuts happens through that inflamed skin, via peanut dust in the environment, and sensitizes the infant to peanuts.

Peanut dust is surprisingly widespread. Researchers at King’s College London, the US Department of Agriculture and elsewhere found that peanut protein sticks to hands for up to three hours after a person’s eaten peanut products, and persists on furniture and pillows even after they’ve been cleaned. Moreover, infants at high risk of allergy, due to a mutation in a gene for their skin barrier, are more likely to become allergic if their homes contain high levels of peanut dust.

And scientists from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, found Ara h 2 on restaurant tables, library tables and frozen yogurt shop counters. It also showed up on the tray tables of airplanes, even when peanuts were not served.

In contrast to dust exposure, eating peanuts may promote tolerance. Pediatricians used to recommend that parents avoid giving infants allergenic foods such as peanuts. A hint that this wasn’t the right approach came from a 2008 study comparing young children in the United Kingdom, where babies didn’t eat peanut products, and Israel, where they did. Peanut allergies were more than 10 times as common in the British children.

To find out if peanut exposure prevents allergy, researchers recruited the families of 640 infants considered at high risk for peanut allergy because they already had eczema, egg allergy, or both. They assigned some to eat peanut products and others to avoid them. When the kids were 5 years old, those who had avoided peanuts were more than five times as likely to be allergic.

The findings prompted the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to issue new guidelines, recommending that babies receive peanut products. The guidelines say that those babies with severe eczema or egg allergy, indicating high risk, should see a specialist for testing and discussion of a safe plan to introduce peanut products.

Peanut therapy

Immunotherapy creates tolerance by repeatedly dosing a person with tiny amounts of the allergen. This causes the immune system to stop making so many allergy-inducing IgE antibodies, and switch to another type of antibodies, called IgG, that don’t trigger the release of histamine. Allergy shots, for allergies like pollen or bee stings, are a form of immunotherapy. For food allergies, an oral version of immunotherapy has been used for a variety of foods such as eggs and milk. Immunotherapy is also available for peanuts in some parts of the world, and in some US clinics, but no commercial treatment has yet been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy, now undergoing testing and perhaps hitting the market soon, likely won’t allow someone with an allergy to eat peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches but could lessen the danger from trace amounts encountered accidentally.

In February, DBV Technologies of Montrouge, France, published its latest trial results from a 356-person study of its immunotherapy patch, Viaskin Peanut, which contains peanut protein. Of children on the patch for 12 months, 35 percent responded to the treatment. From an average tolerance of less than one peanut-equivalent before treatment, the amount rose to more than three peanuts afterwards. The results weren’t quite as good as the company was hoping for, but they still plan to file for a license from the FDA.

Aimmune Therapeutics in Brisbane, California, is testing peanut protein powder that patients mix into foods to get their daily dose. The company recently tried out the regimen in 496 children and teens. In February, they announced that after a year of treatment, two-thirds of the 372 kids who received the peanut protein (as opposed to a placebo) were able to tolerate the equivalent of at least two peanuts. Of 20 adults who completed the treatment regimen, 85 percent could tolerate two peanuts. The company plans to submit a license application.

In more preliminary studies, researchers are looking at liquid drops that people could take under the tongue. In a study of the drops reported in 2017, 32 out of 37 allergic children were able to eat the equivalent of one or more peanuts following treatment. Larger studies are needed before the drops can move closer to the clinic.