Coronavirus evolving: How mutations arise and new variants emerge

By Diana Kwon and Illustrated by Maki Naro COMIC: As it spreads throughout the world, the virus that causes Covid-19 has been changing. Scientists are tracking those changes, hoping to stay one step ahead of worrisome strains. Read more.

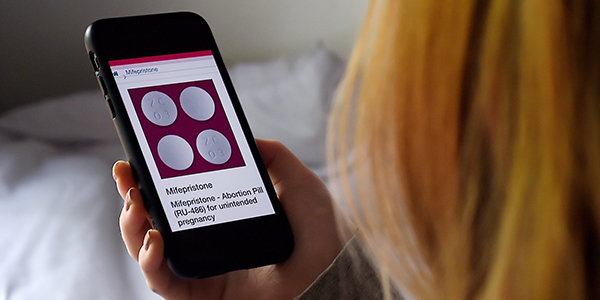

Abortions can happen safely — and entirely — at home

By Leah Coplon and Claire Brindis OPINION: The pandemic has taught us how we can deliver better care to patients who seek to terminate pregnancies. Now if only science could triumph over politics. Read more.

ICYMI: Last week’s online event

How has the pandemic influenced public attitudes toward science?

VIDEO: It’s not too late: Watch the conversation with Cary Funk, director of science and society research at the Pew Research Center, and Harvey Fineberg, president of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, about how understanding of and trust in science have changed in the past year. Watch now.

From the archives

Out of Antarctica, churnings of climate change

By Anil Ananthaswamy A system of Atlantic Ocean currents that includes the Gulf Stream is weakening, adding to concerns of sea levels rise on the US east coast, severe winters in Europe and more, Fiona Harvey reports in the Guardian. Brush up on the role of the ocean circulation in the present and future climate. Read more.

Expert take

Strictly speaking

When people are exposed to perceived threats, they see norm-violators in more of a negative light. So says Michele Gelfand, a psychologist at the University of Maryland. Back in 2011, Gelfand demonstrated this phenomenon in a quirky ad-hoc experiment: She got her research assistants to plant themselves outside local Washington, DC, movie theaters to catch movie-goers before and after watching the movie Contagion — in which a respiratory bat virus causes a global pandemic. When questioned, people rated norm-violating activities — such as cheating on taxes — as less justifiable after watching the movie.

Nine years later, when a pandemic threatened in real life, Gelfand figured that even fairly permissive Americans would start to lean toward upholding rules, just like the movie-goers. But by March, it was apparent this wasn’t the case — rather than Americans tightening up around Covid, the national response seemed like a disorganized mess. Concerned, Gelfand wrote an op-ed for the Boston Globe, urging readers to temporarily sacrifice liberty for stricter rules to save lives. And she told her grad students they’d be pivoting to studying how levels of cultural permissiveness in different countries played into Covid responses and how quickly they tightened up.

The newly published analysis of 57 countries found that looser, more permissive cultures tended to have higher Covid cases and deaths than stricter ones. But strict cultures aren’t better in all respects, Gelfand stresses: More permissive societies tend to be more creative and innovate more, for example — a positive characteristic that helps nations problem-solve and thrive. The trick, she adds, is figuring out how organizations, be they nations or companies or households, can develop what she calls “cultural ambidexterity” — the ability to tack more strict or less, as the wind changes.

Editor’s note: This text was updated on July 8, 2021 to correct the description of the Contagion study.

What we’re reading

Elemental woes “Save the (p)ee,” pleads a button worn by ecologist Jim Elser. Humanity could be facing a phosphorus crisis, and researchers such as Elser are looking at how to recapture the element from human and animal waste, writes Julia Rosen at the Atlantic. Phosphorus is essential to life, but industrial sewage processing has robbed crop fields of a once-reliable source, and phosphate mines may be running out. At the same time, phosphorus pollution is widespread, wasting the resource and endangering ecosystems. As one researcher puts it, “we have a too-little-too-much problem.”

Retro-viral As most of us know, Covid-19 is not the first disease to wreak global havoc. For a slideshow-like roundup of the 11 worst pandemics in history, read Michael S. Rosenwald’s infographic at the Washington Post. With stark white words on a black background, each of humanity’s major plagues is described in brief, from infamous killers like the Black Death to lesser-known foes like the H2N2 flu of the late 1950s.

Woof and wool Weaving blankets from the fur of man’s best friend sounds a bit like a folktale. But then zooarchaeologists in the Pacific Northwest probed buried bones and old Indigenous textiles for domestic dog DNA, writes Virginia Morell for Hakai Magazine. It turns out that small, white, woolly pups were part of the coastal communities for millennia and were likely selectively bred to bear bountiful coats.

Art & science

CREDIT: WELLCOME COLLECTION (CC BY 4.0)

Dressed for the plague By now, we’ve gotten used to masks and Plexiglas separating us from grocery store clerks, barbers, doctors and each other. While our constant brushes with PPE can feel sterile and draining, some might argue that contemporaries of pandemics past had it much worse. Consider the “plague doctor,” a foreboding and ubiquitous figure of 17th century Europe, contracted by towns trying to claw their way out of the grip of bubonic plague. Medical experts back then thought the illness was caused by poisoned air, or “miasma,” and the PPE they donned in hopes of protecting themselves was a thing of children’s nightmares.

“This fanciful-looking costume typically consisted of a head-to-toe leather or wax-canvas garment; large crystal glasses; and a long snout or bird beak, containing aromatic spices (such as camphor, mint, cloves, and myrrh), dried flowers (such as roses or carnations), or a vinegar sponge,” writes the Public Domain Review. The bubonic plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, and most of the plague doctors’ common prescriptions, like urine baths or inhaling “bottled wind,” undoubtedly did little to help the victims. The terrifying getup ultimately inspired theater, paintings, carnival outfits and some bizarre online cosplay popularized by Pandemic 2020. Browse a collection of plague doctor memorabilia from the 1700s onward.