Kevin Lafferty gets more than his share of intimate disclosures from strangers about their anatomy and bodily functions.

Graphic details and pictures arrive steadily via email, from people all over the world — a prison inmate in Florida, a social psychologist in Romania, a Californian afraid he picked up a nasty worm in Vietnam — begging for help, often after explaining that doctors will no longer listen. Do I have bugs burrowing into my brain? Insects poking around under my skin? Creatures inching through my intestines?

Lafferty has learned to open letters and packages carefully. On occasion, they contain skin or other suspect samples in alcohol-filled vials.

“Sorry to hear about your health troubles,” Lafferty wrote recently to one man who asked him to help identify a worm found wriggling in the toilet bowl. “Undercooked fish (and squid) can expose you to many different types of larval parasites that … can accidentally infect humans, sometimes making people sick.”

“The photo that you sent does not look like a tapeworm (or a parasite) to me, but it is not sufficient quality for identification,” he gently informed another, whose email included extreme close-up pictures of a white, bumpy tongue and noted that emergency hospitals keep referring the stricken man to “psychiatry.”

Lafferty is not a medical doctor — he’s a PhD ecologist who studies parasites, mostly in fish and other marine creatures, a fact he’s always careful to explain to his correspondents. He’s sympathetic to these desperate people, even if what ails them is more imagined than real. Parasites, after all, have wormed into every corner of the tapestry of life, including hooking up with human beings in the most unpleasant of ways.

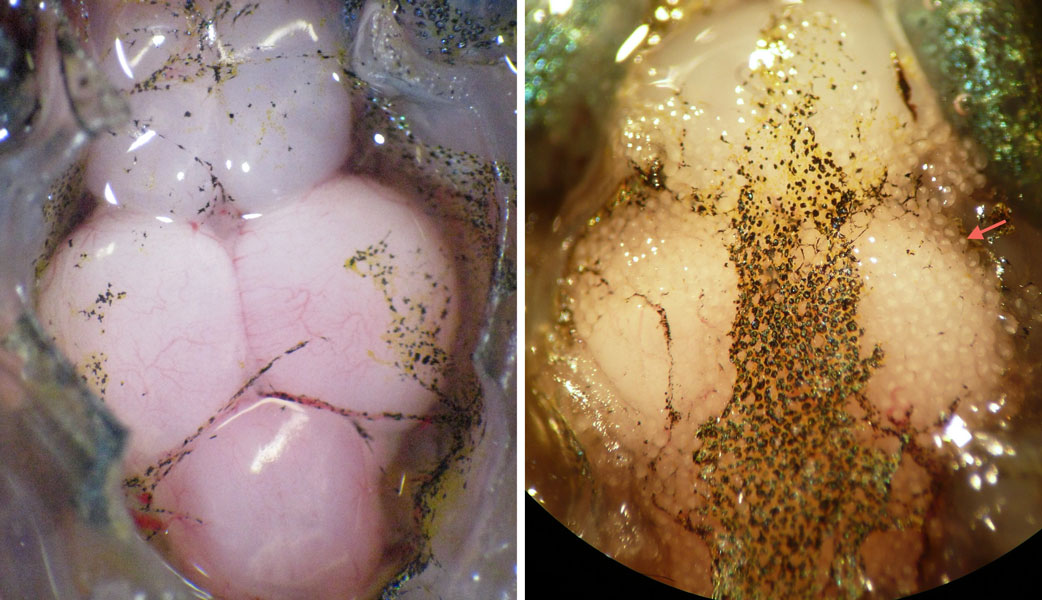

It’s dissection day in the lab at UCSB. Kevin Lafferty examines a slide of a parasitic copepod found in the gills of a horn shark. The copepod had its own parasitic worm attached to an egg sac. “That’s beautiful,” Lafferty says, complimenting PhD student Dana Morton (not pictured), who found the parasites and prepared the slide. “There are not a lot of illustrations of parasites on parasites.” Technician Ronny Young and PhD student Marisa Morse look on from the background.

CREDIT: KENNETH R. WEISS

Yet his own view of parasites is more expansive than that of veterinarians, physicians and public health researchers, who tend to vilify these freeloading worms, bugs and protozoans as nasty culprits behind outbreaks of disease. Lafferty reminds us that parasites are not lesser life forms hell-bent on exploiting the weak and degraded, but rather an overlooked, misunderstood and even glorious part of nature. He celebrates them.

“Don’t get me wrong, I don’t want to be parasitized and I wouldn’t wish it on others,” he says in his laboratory at the University of California, Santa Barbara. But over three decades of studying parasites he has grown to admire their ingenious and complex lifestyles as they hitch rides on hosts that swim, run, crawl, climb or fly around the globe. He cut his scientific teeth studying parasitic worms that castrate their hosts (and thus, from an evolutionary standpoint, transform them into the living dead). In recent years, he’s become enthralled by tiny parasites that brainwash those they infect, turning them into zombies or pushing the hosts to engage in crazy, life-threatening behavior.

“Many of them are fabulous examples of evolution,” he says, “and sometimes incredibly beautiful in terms of the things they do to make a living on this planet.”

Parasites have an underappreciated importance, he adds — as indicators and shapers of healthy ecosystems. They thrive where nature remains robust, their richness and abundance keeping pace with biodiversity. They can serve important roles in maintaining ecosystem equilibrium. For all these reasons and others, he urges fellow scientists to take a more neutral view of them and adopt well-established theoretical approaches for studying diseases on land to better understand how marine parasites operate. If scientists want to better predict when infections and infestations will recede, remain innocuous or spiral out of control, he says, they need to start thinking like parasites.

An animated video explains the importance of including parasites in food webs.

Up from the mud

On a cold winter day, Lafferty is wading in the black muck of the Carpinteria Salt Marsh, about a 20-minute drive down the coast from his Santa Barbara home and laboratory. Despite the frigid air that has dipped into California, he is wearing his typical uniform: surfer board shorts, flip-flops and a light gray hoodie sweatshirt emblazoned with the logo of the US Geological Survey (USGS), his employer of two decades. Introduced by mutual friends years ago, I’ve gotten to know Lafferty as a friend at dinner parties and as a fellow surfer.

He picks up a handful of horn snails from the sucking mud. Lafferty began collecting these small mud snails three decades ago, and found that about half are chockablock with parasitic flatworms called trematodes, which eat the snail’s gonad and transform the mollusk into a neutered, hard-shelled meat wagon. They ride around inside for the rest of the snail’s natural life — a dozen years or more — feeding on the infertile gastropod while pumping out trematode larvae into brackish waters. The snails in Lafferty’s hands are likely infected with one of 20 different trematode species, he says: “For the host horn snail, it’s a bad outcome, a fate worse than death. For the parasite, it’s an awesome and sophisticated strategy.”

Lafferty collects California horn snails at Carpinteria Salt Marsh, where he has spent decades studying the roles that parasites play in marine ecology.

CREDIT: KENNETH R. WEISS

The flatworms in these snails may not be destined for a lowly existence in the mud, though: Their future holds an opportunity to swim, and even fly. Larvae of the most common species go on to penetrate the gills of a California killifish, then attach themselves by the hundreds to the fish’s brain, manipulating the new host to dart to the surface or roll on its side and flash its silvery belly.

That conspicuous behavior makes the infected fish 10 to 30 times more likely to be eaten by a predatory heron or egret. And it’s in that bird’s intestine that the trematode finally matures, excreting eggs that are dispersed with guano all over the salt marsh or in other estuaries — before being picked up, again, by horn snails.

Parasites have altered the way Lafferty sees the salt marsh and beyond. A great egret flies by, flashing its brilliant, white wings. Sure, it’s gorgeous, but it’s a lightweight in this neighborhood compared to the parasites. Lafferty and colleagues once determined that the collective weight — or biomass — of trematodes in this salt marsh and two others in Baja California, Mexico, is greater than the collective weight of all the birds that live in the same three estuaries.

Hundreds of larvae from the parasitic trematode Euhaplorchis californiensis can latch onto the brain of the California killifish. Collectively, they manipulate this intermediate host in West Coast estuaries to dart to the surface and flash its silvery belly, making the killifish far more likely to be eaten by a predatory bird. The larvae mature in the intestines of the bird, their final host, before releasing eggs to be dispersed with guano into the estuaries and picked up again by horn snails. The brain on the left is uninfected; the one on the right is infected. A red arrow points to one of the many parasite cysts.

CREDIT: KELLY WEINERSMITH

Lafferty spots an osprey in the distance, and trains his spotting scope to watch as the fishing hawk rips apart and bolts down chunks of a mullet held in its talons. “We’re watching a transmission event,” he says. “That mullet had hundreds of larval trematodes in it. It’s like eating a bad piece of sushi.”

By some estimates, nearly half of the species in the animal kingdom are parasites. Most of them remain largely out of sight because they are small, even microscopic. Their ancestors didn’t always start with a parasitic lifestyle: Researchers have so far found 223 incidents where parasitic insects, worms, mollusks or protozoans evolved from non-parasitic predecessors. Some ate dead things. Others killed their prey and consumed it. Then their life strategy evolved because they proved more successful if they kept their prey alive, kept their victims close — so they could feed on them longer. It’s a strategy distinct from those of parasitoids, which outright kill their hosts, Lafferty explains, a glint of mischief in his eye. “Think about the movie Alien. Remember when the alien sock puppet bursts its head out of John Hurt’s chest? That’s a classic parasitoid.”

Lafferty revels in such parasite talk, enjoying the reaction from lecture audiences or gatherings of friends. From personal experience, I can attest that he’s not beyond rolling a pre-dinner video for surf buddies in which one moment he’s landing a five-foot wahoo in the tropical Pacific — and in the next, he’s in the lab extracting thumb-sized, blood-engorged parasitic worms from the fish’s intestines. He squeezes the dark, congealed blood from the worms, fries them up with a little garlic and butter, pops one in his mouth and then, with a smirk, holds out the skillet and dares a grad student to give it a try.

He is also a serious marine ecologist who holds passionately that parasites are worthy of study for how they influence ecological systems and how ecosystems influence them. For years, it was a fairly lonely position to take: “Ecologists have built hundreds of food webs and they haven’t put parasites in them. And what we’ve lost from that is the ability to even think about parasites and their role in ecology,” Lafferty says. Ecology conferences used to struggle with where to place Lafferty’s talks in their schedules, but nowadays the meetings have dedicated sessions on wildlife infectious diseases. And ecologists, especially younger ones, are starting to recognize that they are missing part of the story if the food webs they model don’t include parasites that can influence predator-prey relationships and competition for resources. As illustrated by the trematode in the killifish, Lafferty says, “parasites are determining who lives and who dies in a way that benefits them.”

Moreover, parasites are a useful way to explore broader ecological questions: How does energy flow through those food webs? What forces maintain ecological stability and keep one species from overrunning all others? What are the implications of robust and healthy biodiversity on human health? Ecologists debate all sorts of competing theories, Lafferty says. What’s clear to him and other like-minded parasitologists: “We cannot answer these questions if we are going to ignore the parasite part of the equation.”

But first, a scientist needs to overcome the ick factor — just as Lafferty did 30 years ago. He calls himself an “accidental parasitologist” to this day.

The making of a model surfer

Born in Glendale, California, in 1963, Kevin Dale Lafferty was raised in nearby La Cañada, the son of a mother who wrote a book and taught classes on earthquake preparedness and a father who was an aeronautical engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He fell in love with the ocean during boyhood vacations in nearby Newport Beach and Laguna Beach.

He bodysurfed. He snorkeled. He caught mackerel off the pier and pried mussels and crabs off its pilings — matching his discoveries to those described in Ed “Doc” Ricketts’ classic guidebook, Between Pacific Tides. At 13, he knew his destiny: become a marine biologist. At 15, he learned to scuba dive and, while in high school, built underwater camera housings out of Plexiglas.

Once enrolled in aquatic biology at UCSB, he learned he could walk from the dorms with a board under his arm to surf. Tanned and fit, he modeled bathing suits (“It was a good way to meet girls”) and wasn’t a particularly serious student until he reached the more interesting upper-division courses in marine ecology.

A rare giant sea bass surprised Lafferty while he was collecting fish to look for parasites in waters off Santa Cruz Island in the Channel Islands National Park. Lafferty says the close encounter with this protected giant fish made this one of his Top 10 dives.

CREDIT: DAVID KUSHNER / NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

His youthful passions most certainly did not involve parasites. But while on a student field trip to nearby mudflats, he met UCSB parasitologist Armand Kuris. Kuris was so impressed with Lafferty’s smarts and their easy flow of conversation that he tracked Lafferty down on campus and recruited him to join his lab as a PhD student. Lafferty agreed on one condition: He would study marine ecology, but not parasites. “I found them disgusting.”

The Santa Barbara campus, situated on a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean, has a powerful allure to marine scientists, beach lovers and surfers. It has three premier surf breaks, substantial waves in the fall and winter, and glorious weather nearly year-round. It also has a laid-back style that makes even the most hard-charging professors more collaborative than cutthroat.

Graduate students, particularly those in the marine sciences who surf, never want to leave. Those who manage a rewarding surf-adjacent career can be the targets of considerable envy. When Lafferty’s work, years after his student days, was featured in the Canadian television series The Nature of Things, video images showed him catching and riding a wave with a classic surf rock song, “California Baby,” filling the soundtrack. Show host David Suzuki introduced him this way: “Kevin Lafferty… has a rough life.”

Lafferty holds a California horn snail, Cerithideopsis californica, which has an even chance of being infected with one of 20 species of parasitic flatworms called trematodes. As parasitic castrators, these trematodes consume the snail’s gonad and then ride around in the host for the rest of its natural life.

CREDIT: KENNETH R. WEISS

Suzuki didn’t know the half of it. Not only did Lafferty manage to stay at UCSB after grad school (by snagging a job with the USGS that permitted him to work from the university), but he ultimately took up residence in the only home on a 170-acre protected area next to campus, the Coal Oil Point Natural Reserve. And it just happens to have an unobstructed view of 30 miles of coastline and unrivaled access to the surf he loves so much (he self-published a guidebook, The Essentials of Surfing, in 2013). “It looks like he has it all, but he did it piece by piece,” says Kuris, who has now collaborated with Lafferty for nearly three decades. “You only do that if you have a high level of self-confidence. Kevin was committed to his geography. I knew he was serious when he gave up a two-year postdoc in Cambridge.”

One critical life piece fell into place soon after Lafferty joined Kuris’s lab to pursue his PhD. It so happened that the only job available to fund his graduate work was as a teaching assistant in the parasitology class, the topic that so revolted him. As he was learning about parasites so he could teach the course, he realized that all of the marine creatures he thought he knew so well — ever since his boyhood curled up with Between Pacific Tides — were full of parasites. And in many cases, the parasites were having their way with his beloved abalone, sea stars and sand crabs.

It hit him that here was an opportunity to break new ground. “Although lots of people had studied parasites for their own sake, or as problems to be solved, it seemed like an open playing field to start asking how parasites fit into natural ecosystems,” he says. He spent the next two years cracking horn snails with a hammer to collect trematodes in estuaries from San Francisco to Baja. His work solidified how the parasites were affecting the snails’ abundance and evolution — finding, for example, that snails in areas with high infection rates have evolved to mature and reproduce early, before they get castrated.

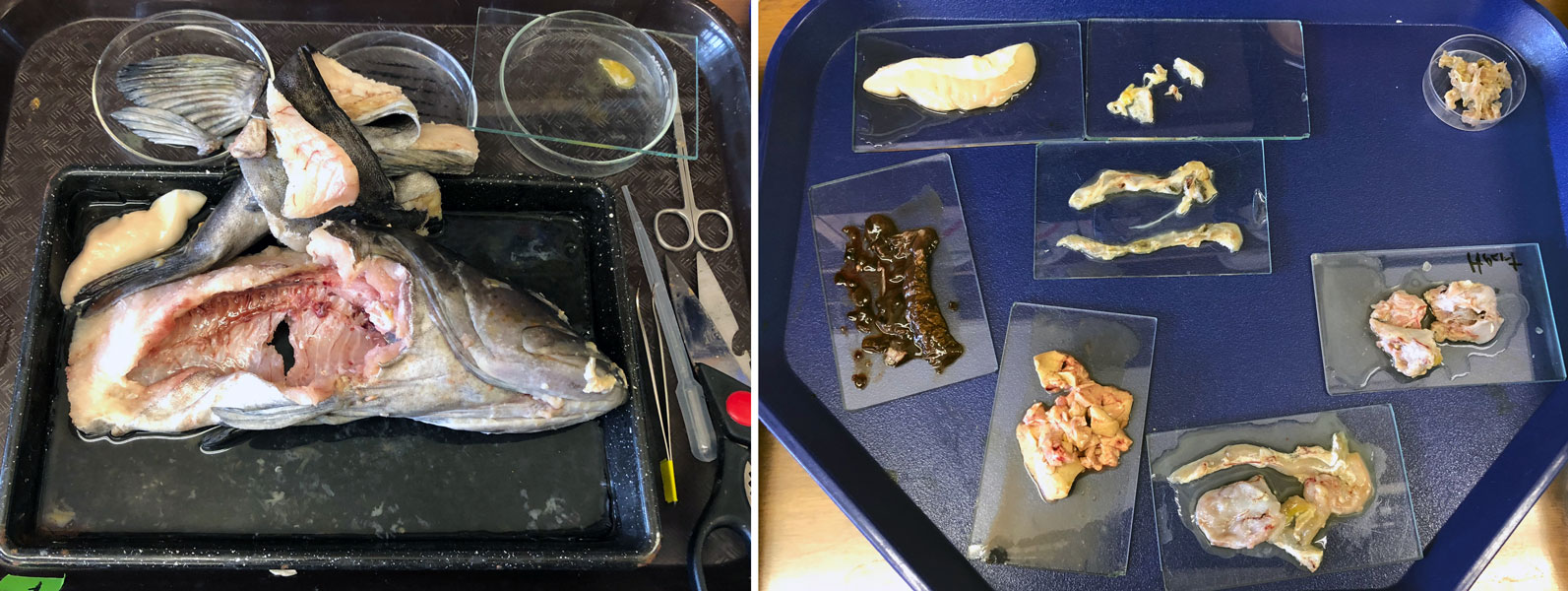

Pursuing parasites in the lab: Step One — discard the filet from this ling cod. Step Two — place the gills, gonad, liver, intestines and other organs on glass plates to be squashed for examination under the microscope. Parasites are ubiquitous in nature; many of these freeloaders hitch a ride without seriously impairing their host.

CREDIT: KENNETH R. WEISS

Another life piece emerged in his second year of grad school, when a new PhD student arrived from Brazil. She’d recently completed a master’s on social spiders that cooperate to weave webs the size of volleyball nets. Cristina Sandoval moved into the office across the corridor in Noble Hall, which housed the usual assortment of beach-casual grad students studying ecology and evolutionary biology. She showed up every day wearing high heels, stockings, gloves and pillbox hats. “No one knew what to make of her,” Lafferty recalls. She needed help to learn English. He volunteered.

One marriage, two children and three decades later, they live in a blufftop doublewide trailer in the Coal Oil Point reserve. Sandoval, a PhD evolutionary biologist, has spent more than 20 years as the reserve’s director, managing a small army of docents and volunteers who protect the shoreline, dunes, estuary and the western snowy plover, a fluffy little shorebird threatened with extinction. She’s celebrated for innovative approaches, such as grabbing marauding skunks by the tail before they can eat plover eggs. Once hoisted aloft, skunks are incapable of spraying. Or so she says.

In addition to the USGS job, Lafferty codirects the Parasite Ecology Group at UCSB, which provides him an office and lab space. Although he doesn’t teach regularly, he mentors a half-dozen PhD students and a couple of post-doctoral researchers. The USGS, which once tolerated his parasitology work, now embraces it because of its value in managing natural resources, including rare and threatened species such as abalone, sea otters and island foxes in the nearby Channel Islands National Park.

Lafferty’s day begins at dawn as he walks the family dog, Hubble, and checks the surf from the bluff. Forget that image of the slacker surfer: Lafferty is as disciplined with his surfing as he is with his science. At age 55, he surfs more than he did when he was 40. He knows this because he tracks every surf session, as well as every session in the gym, and every pound of weight he’s carrying, in an Excel spreadsheet. Pie charts and fever graphs reveal, through an elaborate point system, if he has met his goal for the week, the month, the year. He refuses desserts with sugar. Beer gets banished any time he tips the scale above 160 pounds. His wife finds his discipline a bit strange; his colleagues find it enviable, an extension of his intense work focus.

Lafferty catches a wave near Santa Barbara, California, where he lives and works studying marine creatures from microscopic parasites to great white sharks.

CREDIT: KENNETH R. WEISS

Colleagues point to how Lafferty can quickly size up the science, map out the fieldwork and then plow ahead without distraction. “I’ve worked with finishers before, but he’s quite remarkable,” says Peter Hudson, a wildlife disease ecologist at Pennsylvania State University. “He does it. He finishes it and he publishes it. He’s a machine.”

All told, Lafferty has published more than 200 articles in Science, Nature, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and other peer-reviewed journals. Much of his work focuses on parasitology. He and colleagues worked out how to halt an epidemic of schistosomiasis in Senegal by reintroducing freshwater river prawns that eat the intermediate host of the blood fluke that causes the disease. He discovered how the eradication of rats on Palmyra Atoll in the Central Pacific had a second benefit: the local extinction of the Asian tiger mosquito, a vector for the dengue and Zika viruses. His work often veers into other topics of marine ecology and conservation biology, such as recently detecting the presence of white sharks near Santa Barbara by collecting seawater samples with telltale environmental DNA.

Hudson and other collaborators say that Lafferty is an astute naturalist as well as a solid scientist who understands theory and how to design an experiment that will yield the data needed to test a hypothesis.

“He’s one of the top people in both areas, and that is rare,” says Andrew P. Dobson, an infectious disease ecologist at Princeton University. “We have had tremendous fun together. It’s as much fun writing down equations on a blackboard as it is digging through the mud looking for creatures.”

Lafferty also is one of the few federal researchers to be promoted to senior scientist in the USGS, with a rank and pay grade similar to that of a brigadier general in the Army. “He’s unusual as a federal scientist,” says James Estes, a former USGS researcher and emeritus ecologist at UC Santa Cruz. “There are not many as creative and productive. He’s a top scientist by any metric.”

Although he comes across as even-keeled and dispassionate, Lafferty’s not afraid of calling out a faulty scientific argument, or sticking up for the lowly parasite. Many marine-disease experts come from veterinarian or wildlife-welfare backgrounds. Their mission, as they see it, is to minimize the impact of parasites on wildlife. Lafferty, as an ecologist, views parasites as part of nature, not a scourge to be wiped off the planet.

He doesn’t mind ruffling feathers. In 2015, he wrote a paper, “Sea Otter Health: Challenging a Pet Hypothesis,” that questioned a well-publicized scientific theory that polluted urban runoff carrying domestic cat feces was infecting the adorable, button-nosed otters with toxoplasmosis. The data showed the opposite was true: More otters were infected with toxoplasmosis along the lightly populated Big Sur coast than near the city of Monterey. “I expect,” Lafferty admonished, “that future directions in sea otter health research will continue this recognition that marine diseases are part of nature, and that sea otter parasites might, ironically, indicate wilderness, not a dirty ocean.”

Lafferty has a particular affinity for Toxoplasma gondii, the single-celled protozoan behind toxoplasmosis. It’s his favorite, he says, among the hundreds of parasites known to hijack the brains of their hosts. T. gondii tricks rats into being unafraid and even aroused by the smell of cat urine, which seems to make them more likely to get eaten by a cat. This phenomenon, dubbed “feline fatal attraction,” allows the protozoan to reach its primary host, where it can reproduce and complete its lifecycle.

T. gondii infects warm-blooded animals of all kinds, including as many as two-thirds of the human population in some countries, and nearly no one in others. In the United States, about one in eight is infected. It encysts in the human brain and, although it can cause serious eye and brain damage in a human fetus, is mostly asymptomatic in adults with healthy immune systems.

Or is it? Some studies have suggested that the parasite may have subtle, mind-manipulating effects on unintended human hosts — on traits such as guilt or impulsiveness. Other studies have noted slower reaction times or diminished ability to focus, suggesting these may be why infected people have a nearly threefold higher chance of being involved in a car accident. Lafferty has run with this idea to ask if parasite-triggered personality traits might explain differences in cultures around the globe. He concludes, for example, that T. gondii might explain a third of the variation of neuroticism among different countries.

Lafferty explored these ideas in a TEDx Talk, “A Parasite's Perspective,” delivered in California’s Sonoma County in 2016. He ended with a personal note that his blood test was negative for T. gondii, but that about 100 members of the audience were likely infected. How would they react if they were? “You’ve just learned that in your brain is a parasite that would like nothing better than for you to be eaten by a cat,” he deadpanned. “How do you feel about that shared personality?”

In his UCSB office, Lafferty holds a plush-toy anglerfish knitted by former post-doctoral researcher Julia Buck. The toy is sufficiently anatomically correct to show how the tiny parasitic male anglerfish, colored red, implants himself into the female’s body. The male feeds off his mate’s circulatory system while supplying sperm.

CREDIT: KENNETH R. WEISS

Off the stage, Lafferty says he recognizes that these can be considered wild ideas but he finds them a good way help people think about the role parasites play in the broad ecological picture. He has a healthy skepticism about extrapolating effects in rodent brains to humans, and well understands that correlation between parasites and behaviors does not equal causation. “It’s hard to prove,” he says. But what if there were something to the car crash data? “If that’s true, that’s a big deal. We are talking about thousands of deaths around the world.”

Fair play for parasites

Lafferty is acutely aware that he has a privileged, wealthy worldview of parasites, making it too easy to enjoy such thought experiments or view them as cute little study subjects. “I’ve never lost a child to a parasitic infection or suffered a debilitating illness because of one,” he says, horrible circumstances that occur too often in poor countries.

Still, he hopes that, at least in scientific circles, attitudes toward parasites will evolve the way they have for other threatening creatures such as sharks, wolves and mountain lions — ones that, until recently, we rushed out to exterminate without considering the ramifications.

In an “us versus them” view of the natural world, parasites will usually be put on the other team, he says. But that’s not the only way to think about it. “The key to doing science is you don’t want to be rooting for a team, because it takes the objectivity away,” he says.

“That’s how we are going to understand them: by not taking a side.”