While in “profound rest,” bees’ antennae gradually droop down and slowly sway back and forth, a 1988 study of bees found.

C. HELFRICH-FÖRSTER / AR ENTOMOLOGY 2018 (MODIFIED FROM Walter Kaiser / Journal of Comparative Physiology A 1988)

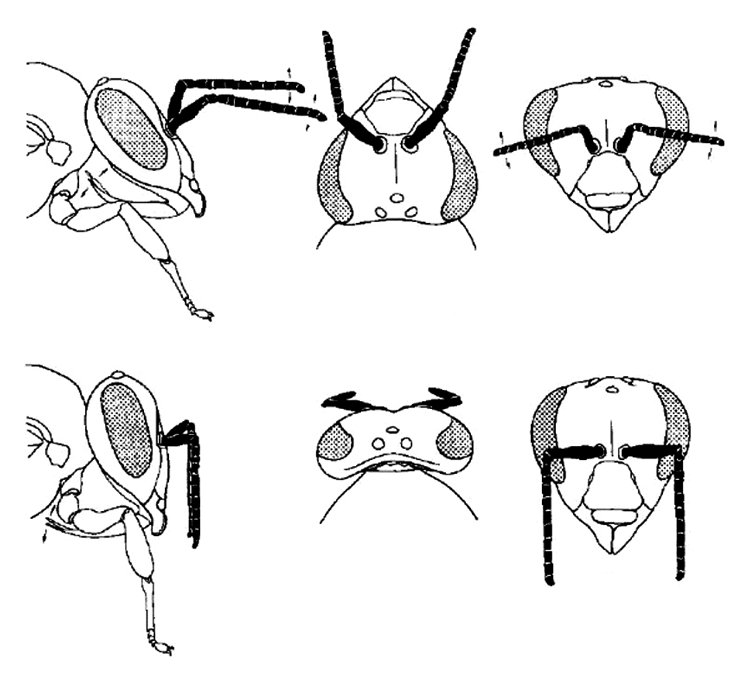

If you watch an exhausted baby carefully, you may be able to see gravity tug heavy eyelids down. Likewise, a sleeping honeybee’s usually perky antennae droop (as illustrated here, the top row shows various views of a honeybee awake, the bottom row shows the insect at rest).

This adorable sign of insect repose may seem unremarkable. But studying insect slumber may ultimately help solve some of sleep’s greatest mysteries, Charlotte Helfrich-Förster of the University of Würzburg in Germany argues in a 2017 review in Annual Review of Entomology. “Because the insect brain is simpler than a mammal’s brain, the study of sleep in insects promises new insights into its neuronal basis and functional role,” she writes. Experiments on the fruit fly, the easily-manipulated lab darling, could be particularly helpful in unraveling the precise brain areas that work together to control sleep, Helfrich-Förster adds.

When entomologist Barrett Klein talks to people about his research on honeybee sleep, the conversations follow a predictable script: “People almost invariably start with the shocker, ‘Insects sleep?’” Then comes a flurry of follow-up questions: “What does it mean to sleep? How do you identify sleep in an insect? Is it related to human sleep?”

To get the preliminaries out of the way, insects do sleep — sort of — says Klein, of the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse. “It depends on how you define sleep,” he says. “Honestly, we still don’t have a firm grasp on what sleep is, in every respect.”

Sleep’s definition is particularly hard to pin down for insects. Clues about whether an insect is sleeping are subtle. Honeybees’ droopy antennae, cockroaches’ crouches and fruit flies’ long periods of stillness may all indicate sleep. But such outward signs aren’t foolproof. A motionless fruit fly might be sleeping or might just be resting.

Methods that measure the brain’s electrical activity may identify sleep, but those techniques aren’t foolproof, either (not to mention that they’re tricky to implement in tiny insects). Other sleep indicators, such as how hard it is to make an insect respond to an external cue, or whether the need for catch-up sleep after an all-nighter exists, might prove to be useful indicators of insect sleep, Klein says.

Definitions aside, more detailed studies on resting insects’ brains reveal parallels to human sleep. Studies of the fruit fly brain have revealed the rhythmic production of proteins that form the basis of the circadian clock. Many of the same proteins are also at work in people and other mammals. Other research on fruit flies has turned up sleep-related jobs for chemical messengers (neurotransmitters) including dopamine, acetylcholine, GABA and others. Mucking with these systems can change fruit flies’ activity and rest cycles, writes Helfrich-Förster.

And just as in people, interrupting insects’ sleep can harm brain performance and change behavior, Klein and others have found. Honeybees perform intricate dances to tell each other where to find flowers. But after being kept awake with an evil lab contraption called the “insominator,” honeybees’ dances grew sloppy, Klein and colleagues reported in 2010 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Unanswered questions about sleep — in insects and in people — abound. “We’re spending so much of our time doing this, and not just closing our eyes or turning off the lights, but really shutting down,” Klein says. And yet, no one knows why. Perhaps insects, which Klein describes as “marvelously diverse, exquisite, behaviorally compelling,” might someday help reveal the answer.