Customs officials in Singapore made a grisly discovery last April at a port on the island’s southern coast. Inside shipping containers supposedly transporting frozen beef from Nigeria to Vietnam, they found bloodstained sacks stuffed with 14 tons of scales stripped illegally from pangolins — scaly anteaters endemic to Africa and Asia. The seizure, worth about $38.7 million, is thought to be the largest bust of pangolin products globally in recent years.

People hunt pangolins for their meat, considered a delicacy in Asia, and for their scales, which are used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat ills such as arthritis. Eight species are now vulnerable or endangered and, in 2016, more than 180 nations banned most cross-border commercial trade in them. They did so under a major international agreement called the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, commonly referred to as CITES. Trade bans on endangered species are the most severe restriction under CITES, which also limits trade in species that are at risk of overexploitation but not yet endangered, requiring permits for their export.

Conservation organizations hailed the pangolin ban as a big win in the war against the multibillion-dollar wildlife trade. But some scientists and wildlife trade experts worry that CITES bans — in this case and others — may be backfiring, by encouraging rather than suppressing trade in a species. “As products become rarer, prices and demand increase. You just hit species all the way into extinction,” says Brett Scheffers, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Florida. Poorly policed trade controls can allow illegal trade to flourish, adds Michael ‘t Sas-Rolfes, a sustainability economist specializing in the wildlife trade at the University of Oxford.

In 1977, for example, an international trade ban on the black rhino led to a tenfold increase in the price of rhino horn over a two-year period, spurring poaching and driving populations to extinction in some areas. And trade restrictions that began in 2013 on species of rosewood helped to make the precious timber the most trafficked group of endangered species in the world.

It’s too soon to know if the same kind of thing is happening with pangolins, but there are troubling signs, says Dan Challender, a conservation scientist specializing in pangolins and wildlife trade policy who works with ‘t Sas-Rolfes at Oxford: Seizures of pangolin parts in high volumes appear to be on the uptick.

There’s no disagreement among researchers that the wildlife trade is a major contributor to the loss of biodiversity worldwide. Where they disagree is over what the countries that are signed up to CITES should do about it.

Many conservation groups say that CITES is one of the best tools they have — enabling signatory nations to ban international trade for species that are already endangered and set limits on trade for species at risk due to trade. But trade experts like Sabri Zain, director of policy for TRAFFIC, a nonprofit group working to make the wildlife trade more sustainable, say that CITES rests too heavily on bans when instead it is meant to help ensure that the wildlife trade meets people’s needs while also safeguarding nature.

“When you talk to people about CITES, the first thing that comes to their mind is trade bans. But the real heart of CITES is sustainability,” Zain says.

Critics also argue that countries don’t adequately apply science to assess whether CITES bans and quotas will work the way they’re intended or make matters worse by sparking illegal trade. All these difficulties have left CITES gasping for breath, says ‘t Sas-Rolfes. “CITES,” he says, “is a terminally ill patient that is in need of serious attention.”

Safeguarding species

CITES was born in the mid-1970s out of public concern that countries were not adequately protecting rare and threatened species. The aim was to encourage governments to restrict imports from nations that lacked protections for plants and animals that are on the “red list” of threatened species as identified by the International Union of Nature Conservation, the globe’s leading authority on the state of the natural world. Today, CITES is a voluntary agreement among 182 states as well as the European Union that protects more than 38,000 species of plants and animals to varying degrees.

To safeguard a species under CITES, a country makes its case for protection — to either ban or limit trade — at the CITES meeting held every two to three years. If two-thirds of member nations vote to approve the proposal, each country then creates laws and systems to implement it. If trade is restricted rather than banned, countries will dole out a limited number of trade permits at levels deemed sustainable for safeguarding a species. Typically, trade restrictions are applied first but if they fail to help populations recover, countries can propose bans.

Legal trade in Asian pangolins dropped to near-zero in the 13 years after a CITES agreement to not export wild-caught pangolins from their native countries, a move that effectively banned international trade. But trade continued — illegally.

Clearly, action is needed. Roughly a million species are threatened with extinction, according to a major international study published last year. And trade and personal use by people is the second leading driver behind habitat destruction, the researchers found.

The devasting impact on global diversity from the harvesting of wild animals and plants makes CITES “one of the most important available tools to address the extinction crisis,” said Mark Jones, head of policy at the conservation group Born Free, and Alice Stroud, director of Africa policy at Born Free USA, in a statement to Knowable Magazine. Once countries restrict or ban trade in a species, that species becomes a high priority for conservation in its native country, they wrote.

In a briefing note, the CITES Secretariat pointed to successes such as the recovery of the pirarucu, the world’s largest scaled freshwater fish at over 3 meters long and 220 kilograms in weight. Pirarucu populations plummeted in the Amazon basin in the late 1960s due to overfishing. Following CITES trade restrictions in 1975, community-led conservation and monitoring programs helped the giant fish bounce back in some areas.

Populations of the endangered pirarucu fish of the Amazon basin have experienced a comeback in some areas following CITES trade restrictions.

CREDIT: VLADIMIR WRANGEL / SHUTTERSTOCK

And at a meeting last August, CITES members agreed to relax a 50-year-old trade ban on an Argentine population of the delicately featured vicuña (Vicugna vicugna) — a cousin of the camel that is prized for its wool — after community-led conservation efforts had helped the species back on its feet. CITES members also agreed that American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) populations in Mexico had sufficiently recovered following conservation and captive breeding programs to allow some trade, which had been banned since 1975.

But bans and trade restrictions don’t always work as intended. For example, a 2010 trade ban on critically endangered European eels (Anguilla anguilla) — driven by culinary demand from China and Japan — hasn’t helped their chances of survival, recent findings show. In 2019, an international anti-trafficking operation announced that illegal fishing is now a major factor in European eel declines, with up to 350 million eels smuggled from Europe to Asia each year.

And legal trade in the tiny Kleinmann’s tortoise (Testudo kleinmanni) skyrocketed in 1994, the year before a ban took effect: Some 2,800 individuals were sold, representing half of the species’ total estimated adult population.

This video describes the problem with illegal trade in European eels, which are critically endangered. Brisk trade continues in spite of a 2010 CITES ban.

CREDIT: AL JAZEERA

Part of the problem, critics say, is that for many species, long-term data on populations are lacking, so that countries can only take a best guess at whether a species is in trouble and, if so, whether that is due to trade. What’s more, the critics add, countries and CITES administrators fail to thoroughly analyze how bans or restrictions might affect trade in the species. An analysis by Challender published April 2019 in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment found that proposals to ban trade under CITES commonly fail to examine markets for wildlife in detail. Of the 17 proposals that were scheduled for a vote at last August’s meeting, including ones for Brazil’s riverside swallowtail butterfly (Parides burchellanus) and the African elephant (Loxodonta africana), Challender found that all but one lacked detailed trade analyses.

The CITES Secretariat said in a statement that the treaty’s administrators do collect data from countries on legal imports and exports, and for some iconic animals they have established more elaborate monitoring systems. The most sophisticated of these tracks illegal killing of elephants and analyzes illegal trade. When wildlife rangers around the world find elephant carcasses, for example, they establish the cause of death and report the information to CITES’s program on monitoring the illegal killing of elephants (MIKE). The information is included in a database and analyzed to help keep an eye on poaching and trends in illegal trade.

But Challender argues that this is not enough. Decisions to tighten trade, he says, need a comprehensive assessment of the likely consequences of doing so — including information on market factors such as retail prices, sales volumes, consumer preferences and social and cultural attitudes to the consumption of wildlife. And when the data suggest that outright bans or severe trade restrictions will not work, those who would safeguard wildlife should look to other creative solutions. “A trade ban may feel intuitively positive but is difficult to predict the outcome for species,” he says.

The case for sustainable trade

Complicating matters are disagreements over how to balance the importance of wildlife for the livelihood of local people and how to best safeguard a species from extinction.

Groups such as Born Free, which prioritizes animal welfare, doubt that wildlife trade could ever be sustainable and thus helpful to conservation. Legal trade creates opportunities to launder specimens obtained illegally, say Jones and Stroud. Ivory products from legal and illegal sources were sold side by side in China prior to the country’s domestic ban on ivory trade in 2017, for example.

But some wildlife trade analysts note that sustainable trade provides a livelihood for people in many communities and constitutes big business in countries like China. Banning or restricting trade when there is little evidence to suggest that tighter controls may help a species, they say, can harm local communities and shift countries’ limited conservation funds away from neglected species.

“From our perspective, a [trade ban] is more a sign of conservation failure rather than a goal to strive for,” Zain adds — because, he says, a ban shows that previous efforts to restrict trade through limited export permits failed to help populations recover.

Zain wants to see more effort put into making trade restrictions work for species by, for example, better assessing species’ populations and how much trade a given population can handle. If these additional efforts fail, countries could then consider a ban.

The CITES spokespeople acknowledged that legal wildlife trade is essential for the livelihoods of many local people but that the extensive data collection advocated by Challender would be too time-consuming and expensive if done for every species under threat. Still, they added, the convention has made improvements. Since 2017, it requires countries to report data on illegal trade garnered from seizures and other violations. Member countries have contracted the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime to develop a database of countries’ illegal trade to make data analysis easier; the office has produced two detailed global reports, the most recent in July of this year.

Beyond CITES

Many experts believe that CITES has a key role to play, but they fear that the wildlife trade is too big and complex for CITES to manage alone. And the international marketplace in wildlife — legal and illicit — stands to grow in the future, Scheffers says. Currently, more than 7,600 species of birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles are traded globally, and Scheffers predicts that another 4,000 or more could be traded in the future. It’s not clear that CITES alone can cope with the scale of the problem.

The wildlife trade is widespread across species in all four groups of vertebrate land animals, with more birds and mammals traded compared to reptiles and amphibians.

So what is the answer? In a paper in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources, ‘t Sas-Rolfes discusses a range of measures beyond CITES that he thinks could make the treaty more effective.

One key tool is local detection of illegal activity, courtesy of new geospatial technologies, in order to catch more poachers. An example is the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool, developed in 2011 by six conservation organizations and now in use in more than 60 countries in Africa, Asia, South America and the Caribbean. Rangers input data onto handheld devices as they patrol. The software takes data on areas surveyed, snares removed and arrests made, and converts them into maps. It also allows rangers to take photos for evidence and identification that the software tags with time and place stamps.

Data are updated in real time, helping to connect rangers in the field to command centers elsewhere, aiding operations as they happen. And knowing where poaching and smuggling has occurred can help rangers better plan patrols and so improve enforcement, the technology’s creators say. They report that the software has saved rangers time and helped operations run more smoothly. That has reportedly contributed to a 67 percent increase in patrols at protected areas in Nigeria managed by the Wildlife Conservation Society, one of the nine groups — and a 71 percent reduction in gorilla hunting there.

A more novel strategy is the development of “synthetic” alternatives to illicitly traded animal products, such as rhino horn and pangolin scales. Introducing cheaper substitutes for wildlife products can drive down prices and reduce illegal harvesting, studies suggest. Researchers have had some success making biofabricated horn from horsehair that is reportedly identical to the wild rhino horn, but the product is not yet on the market and its acceptance — and thus, any conservation benefits — remains to be seen.

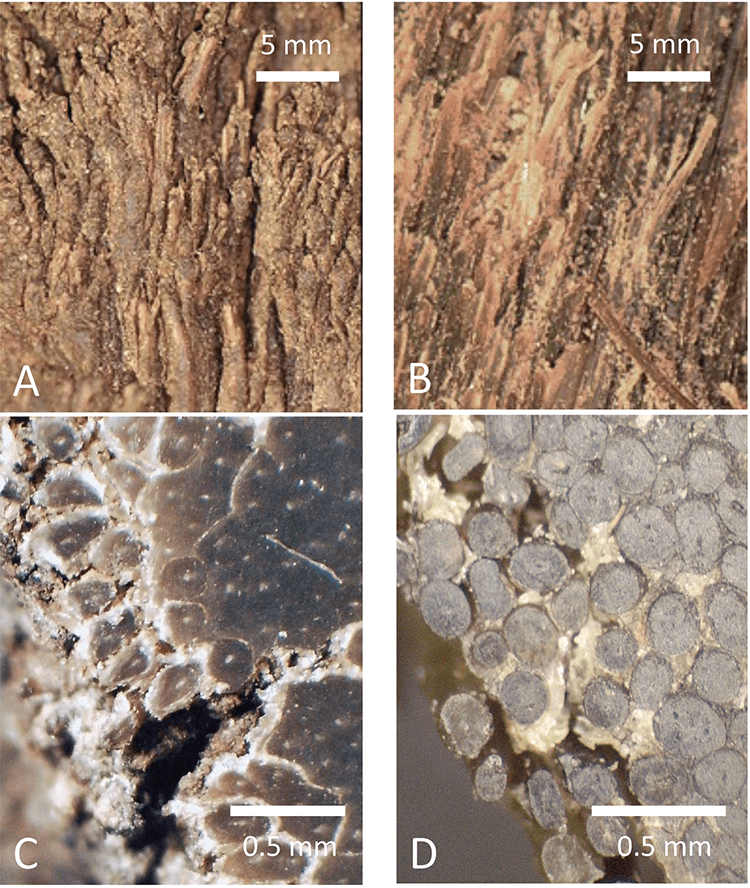

Researchers are working on creating synthetic substitutes for products harvested from endangered species, such as rhino horn and pangolin scales, in an effort to curtail illicit trade. The images on the right (B,D) show a rhino horn substitute made from horsehair that has very similar properties to real rhino horn on the left (A,C) — both are made from the keratin and have fibers of comparable widths, for example. It’s not yet clear how readily consumers will accept such synthetic products.

CREDIT: R. MI ET AL / SCIENTIFIC REPORTS 2019

In a similar vein, Conservation X Labs, a technology company in Washington, DC, that works on solutions to conservation challenges, hopes to develop synthetic pangolin scales as a substitute for the wild-caught product. Alex Dehgan, the company’s cofounder and chief executive, says the project is still in very early stages.

Another, controversial, approach is to raise animals such as lions and bears in captivity to help satisfy consumer demand for wildlife products while protecting wild populations. Such wildlife farming initiatives have had mixed results. South Africa, for example, has legally exported farmed lion parts to Southeast Asia and China to replace the use of wild large cats for tiger wines and health tonics, research reports.

But the program has also been widely criticized for poor animal welfare standards, and wildlife conservation organizations argue that the practice provides cover for illegal trade. “A legal trade removes the stigma attached to wildlife products consumption and increases demand,” Jones and Stroud say.

CITES would also have more teeth if its efforts were linked with other international conservation agreements, Scheffers says — he suggests partnership with the United Nations Program on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation. This would help to foster initiatives that support forest-dwelling people who depend on the wildlife trade for their livelihoods. Local people who are directly affected by CITES rules struggle to get their views and experiences heard in CITES decision-making, Scheffers says; for him and some other experts, this is among the convention’s biggest flaws.

Indeed, ‘t Sas-Rolfes says, for conservation efforts to be effective, they need to involve “the people who have skin in the game on the ground.” Early findings from one of his research projects suggest that governments that encourage participation from local communities are more successful in conserving wildlife and biodiversity. More governments should encourage participation from local communities at CITES meetings, he says, and the meetings should give local people more time and space to express their views. CITES will also struggle to achieve its goals unless it gets better data, Scheffers says.

Still, although CITES has its problems, even its critics aren’t ready to abandon it just yet.

“With all its flaws and faults,” Zain says, “it’s really the only tool out there.”