Teddy Roosevelt called the Grand Canyon one of the great sights that every American should see. And 100 years ago, on February 26, 1919, Congress underscored Roosevelt’s travel recommendation by designating the Arizona canyon a national park.

But the history of the 277-mile-long canyon runs much deeper. Humans first encountered it some 12,000 years ago, as the earliest Americans spread across the continent. By the 16th century a few Spanish explorers began passing through. And in May 1869 the one-armed Civil War veteran John Wesley Powell — future head of the US Geological Survey — led nine men on an unprecedented boating expedition down the Colorado River. His report from that trip, and a second two years later, helped cement the Grand Canyon’s reputation as a national icon and natural wonder.

Today the Grand Canyon hosts 6 million visitors a year, making it the second-most visited US national park after the much more accessible Great Smoky Mountains. Tourists flock to marvel at the canyon’s jaw-dropping immensity, and the sheer spectacle of how the Colorado River carved through layer after layer of rock to expose an ombre of reds, browns, pinks, purples and more.

With 2019 marking the centennial of the national park and the 150th anniversary of Powell’s first expedition, “it’s a good time to look both back and forward,” says Karl Karlstrom, a geologist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque who has studied the canyon for most of his career. “It’s funny — you’d think everything is already discovered in the Grand Canyon because people have been working there for so long. And yet we’re still dramatically changing our understanding.”

Among the new discoveries are updated ages of one of the most important rock layers in the canyon, a finding that shifts key points in its geologic history. Researchers also continue to debate the age of the canyon itself — even as they explore what its future might hold in an era of climate change.

Here, Knowable takes a look at significant milestones in the canyon’s evolution, viewed at a few select moments past, present and future.

More than 1 billion years ago: The foundations are laid

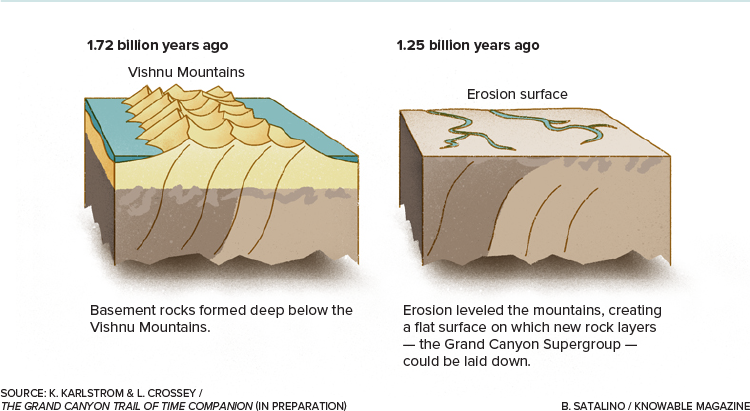

The Grand Canyon’s story began nearly 2 billion years ago, when two plates of Earth’s crust collided. As they came together, rows of volcanic islands smashed together and merged. Under extreme heat and pressure, their rocks transformed into the dark-colored “basement” rocks seen near the bottom of the canyon today — including 1.84-billion-year-old rocks called the Elves Chasm gneiss, the oldest known in the canyon.

For a period after that, between around 1.75 billion and 1.25 billion years ago, the Grand Canyon’s geological history is missing. Erosion erased rocks from that period like chapters ripped out of a history book. The story picks up again between 1.25 billion and 730 million years ago, when new layers of rock, known as the Grand Canyon Supergroup, intermittently formed.

Sediments drifted to the bottom of prehistoric seas and hardened there, forming layers that include a 1.25-billion-year-old limestone studded with fossils of algae, the earliest life recorded in the canyon.

More than 100 million years ago: The upper rock layers settle into place

Geological forces eventually broke the supergroup layers into chunks and tilted them at an angle. Erosion scoured them, and another sea formed atop them. New sediment began settling out at the bottom of the sea — and that is the step that recently surprised Karlstrom and his colleagues.

They decided to analyze mineral fragments from one of the rock layers, known as the Sixtymile Formation. It had never been accurately dated before but was thought to be around 650 million years old. But the mineral study showed it to be just 508 million years old, the team wrote last year in Nature Geoscience. That means that the Sixtymile Formation is not part of the older Grand Canyon Supergroup, but part of the younger group of rocks that formed as sea level rose and waters washed back and forth across the region. Now Karlstrom’s team can use those new dates to better understand how quickly that flooding happened and how rapidly other rock layers formed atop the Sixtymile Formation.

Over the next few hundreds of millions of years, ocean-fed sediments continued to pile up. The rocks that form the upper two-thirds of the canyon walls — the limestones and shales and sandstones of different shimmering colors — belong to this period, between about 508 million and 270 million years ago. John Strong Newberry, who in 1857 became the first geologist to explore the canyon, called them “the most splendid exposure of stratified rocks that there is in the world.” Capping everything, at the canyon’s rim, sits the cream-colored Kaibab limestone which is a relatively sprightly 270 million years old.

Geologists studying the deep history of the Grand Canyon have revealed the complex layers of rock that underlie the giant chasm.

More than 1 million years ago: The plateau rises, the river runs through it

It took eons, but by this point all the canyon’s rock layers had been built. They just needed to be made visible. And that part of the story began around 70 million years ago, as two plates of Earth’s crust crumpled together and began to push up the Rocky Mountains. What is now the Four Corners area of the southwestern US — more broadly known as the Colorado Plateau — began to rise, going from near sea level to thousands of feet high.

Sixty million years ago, the Rocky Mountains and the entire Colorado Plateau, which the Grand Canyon is part of, rose up from tectonic activity. After the top layers of rock (green) eroded away, the Colorado River grew powerful and began to cut its way through the ancient rock, leaving the stunning canyon we see today.

By around 6 million years ago, waters rushing off the Rockies had formed the mighty Colorado River. As the plateau rose, the river cut into it, carving the canyon over time. Smaller rivers eventually cut the side canyons, mesas and buttes that are so characteristic of the canyon today.

Not all geologists agree with the timing of this story. Some have argued, based on how long certain rock minerals appear to have been exposed at the surface in parts of the canyon, that the canyon is as much as 70 million years old. But Karlstrom says that while portions of the canyon might be older, the river system as a whole didn’t get connected and flowing until around 6 million years ago.

More than 10,000 years ago: Humans meet the canyon

As the geological story of the canyon wound to an end, the human story began. People first arrived in the Americas at the end of the last ice age, more than 12,000 years ago.

By around 10,000 years ago they were living in and around the canyon and hunting enormous, now-extinct beasts such as the Shasta sloth (Nothrotheriops). More recently, people living in the canyon made and left split-twig animal figurines that have been dated to about 4,000 years ago. A thousand years ago, people were growing crops along the canyon bottom and stashing their harvests in shelters hollowed from the walls, some still visible today.

During the last ice age, giant ground sloths such as this Shasta sloth roamed the American West (left). The large mammals, which went extinct, are thought to have coexisted with Native Americans who lived in and near the Grand Canyon more than 10,000 years ago. Ancient animal likenesses created from split twigs (right), some as old as 4,000 years, have been found throughout the canyon.

CREDIT: FUNKMONK / WIKIMEDIA COMMONS (LEFT); GRAND CANYON NPS (RIGHT)

100 years ago: The canyon becomes an American destination

Today there are at least 12 Native American tribes who live in or near the canyon, but their lives are dramatically different from times past. In 1882, for instance, the US government restricted the Havasupai to a small reservation at the canyon’s bottom. Instead of moving seasonally to where game was most abundant, the Havasupai were forced to eke out a difficult living in the canyon year-round.

People have used and lived in the Grand Canyon continuously for nearly 12,000 years, according to archaeological finds found within the national park. Here, granaries some 1,000 years old or so perch above Nankoweap, along the Colorado River in Marble Canyon.

CREDIT: NPS PHOTO BY MARK LELLOUCH

And then came the national park, and the attention of travelers far and wide.

Since then, the river’s ecosystem has also dramatically changed. Although environmentalists were able to keep the Colorado River from being dammed near the Grand Canyon itself, the government built a dam further upstream, at Glen Canyon, in 1963. Natural floods no longer replenished sediments on the riverbanks, and so sandbars and beaches began to erode. Invasive species such as the tamarisk tree (genus Tamarix) moved in and crowded out native species.

Eight times since 1996, most recently last November, officials have released controlled floods from the Glen Canyon Dam, to try to restore some of the sediment along the riverbanks downstream and reverse the ecological damage the dam has brought to the canyon and elsewhere.

100 years from now: Climate change threatens the park

The canyon’s geological and human stories collide when it comes to thinking about the future — especially about the role of water in the American West as climate changes. The Colorado River supplies water to millions of people in seven states as well as Mexico. Already it is overtaxed. Streamflow from the river’s headwaters has dropped by more than 16 percent over the past century, mostly because of warmer temperatures and reduced snowfall. As water managers decide how much water to keep behind Glen Canyon Dam and how much to release downstream, the river ecosystem in the Grand Canyon is but one of many competing users.

Another pressing issue for the park is how to supply enough water for the millions of tourists who drink, wash up, flush toilets and otherwise use water each year. Slaking the thirst of the visitor services on the heavily developed South Rim involves pumping 500,000 gallons of spring water daily across the canyon from underground springs on the North Rim. But the piping system dates to the 1960s and frequently breaks. And the hydrological plumbing that feeds the springs is complicated.

One of the most immediate concerns for geologists studying the Grand Canyon is how climate change might affect it. One worry is the sustainability of the water supply.

Climate models indicate that winter snowpack will diminish, and it’s not at all clear whether the springs on the North Rim will continue to be able to supply enough water. Already, springs in some other regions of the canyon have dried up in recent years. Visitor demand, nearby mining and climate change all threaten the canyon’s water supply, says Laura Crossey, a geochemist at the University of New Mexico.

The canyon, with roots dating back billions of years, might shrug off such changes, but water issues could soon pose a challenge for the humans who come to marvel at it. “Who knows," Karlstrom asks, "where we’ll be in 100 years?”