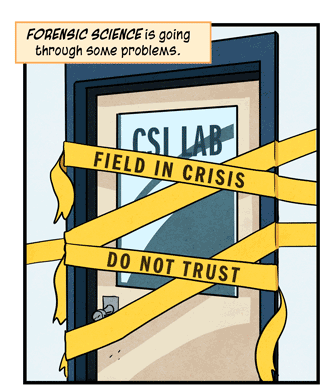

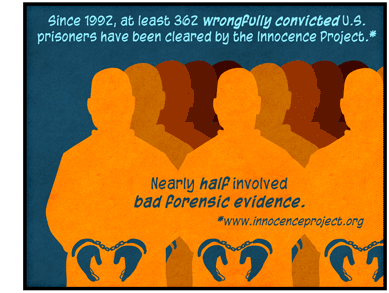

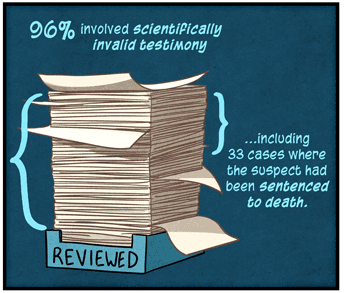

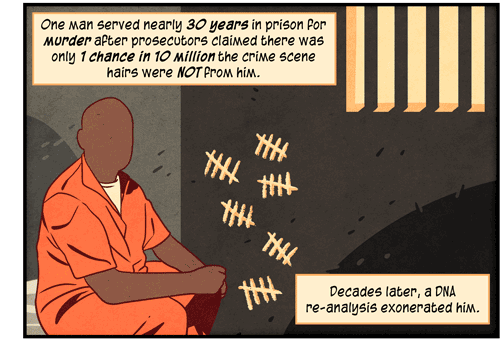

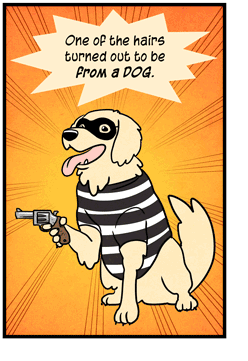

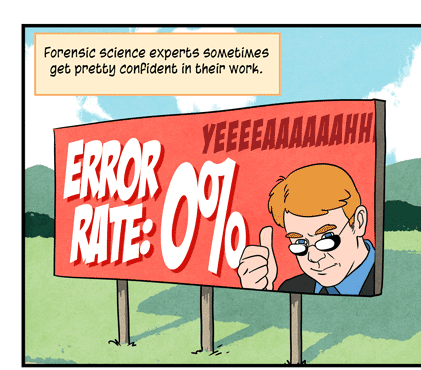

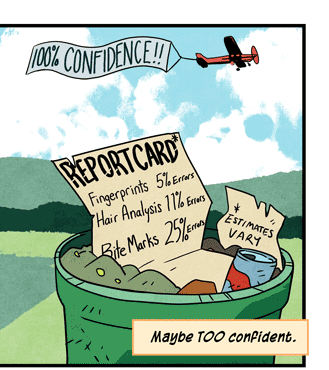

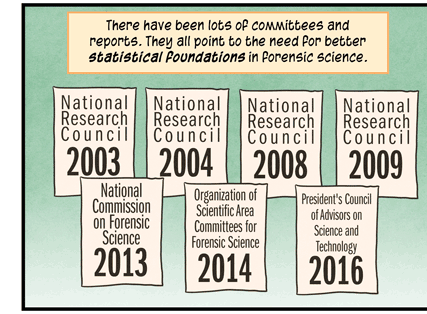

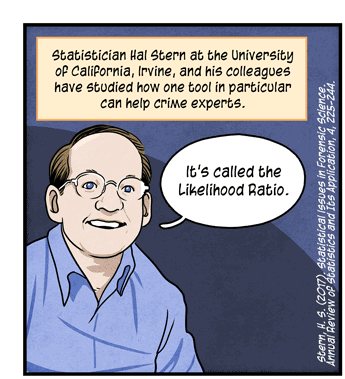

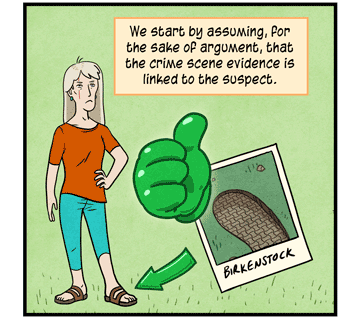

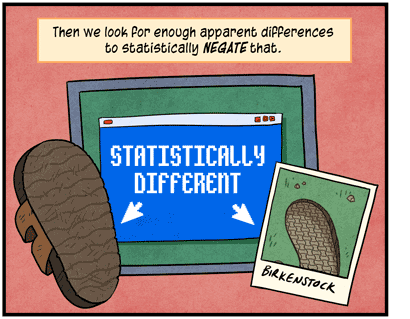

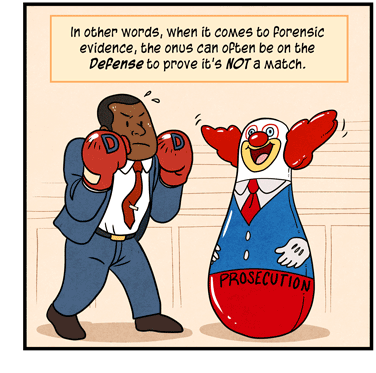

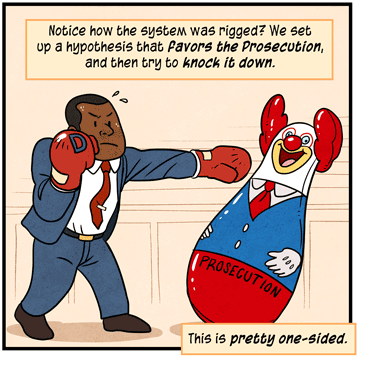

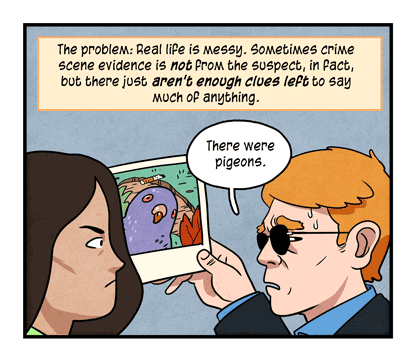

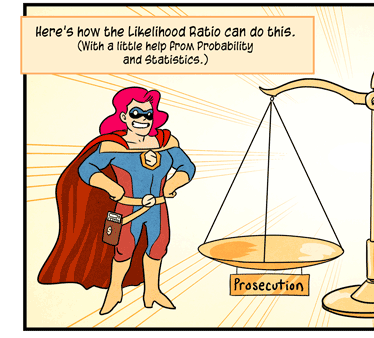

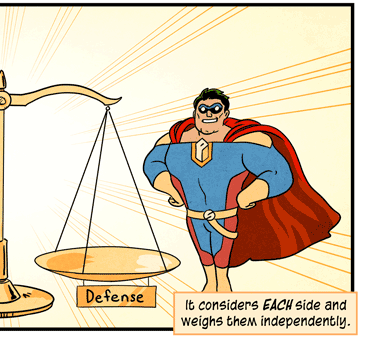

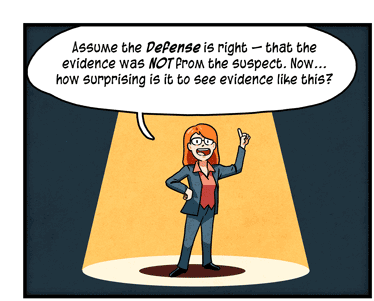

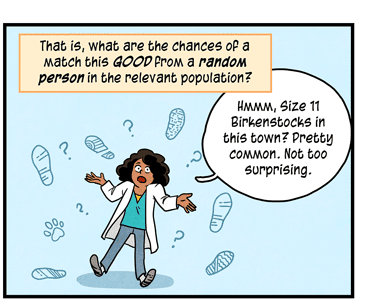

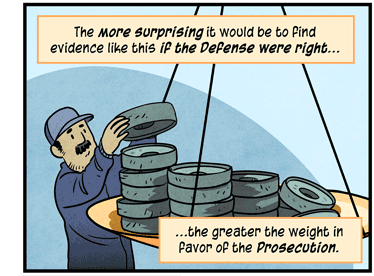

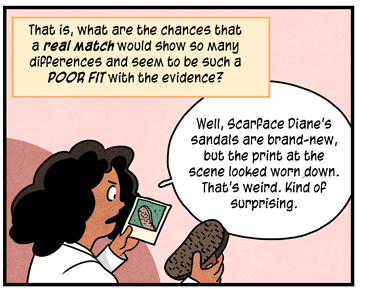

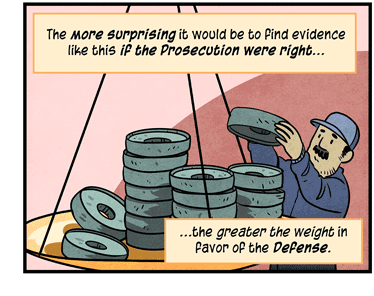

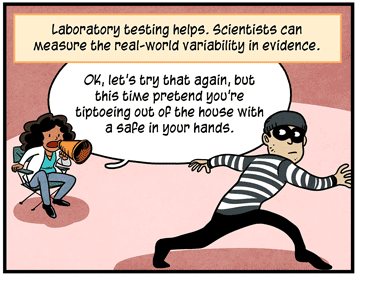

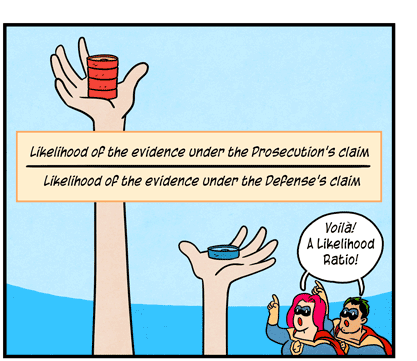

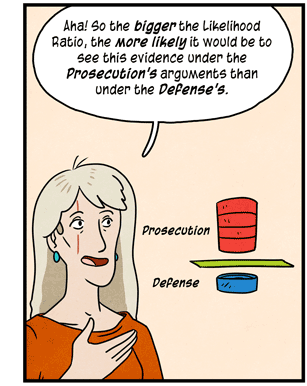

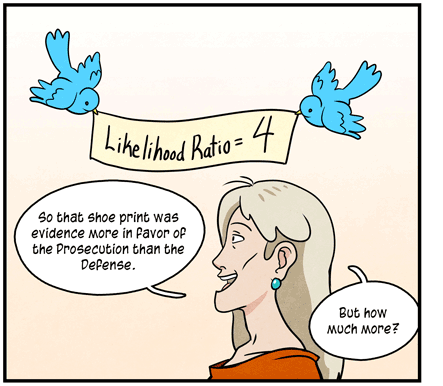

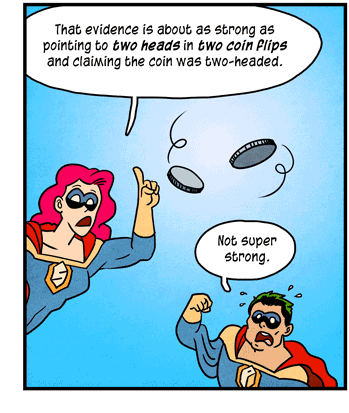

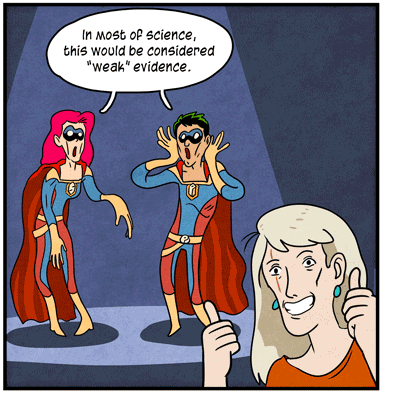

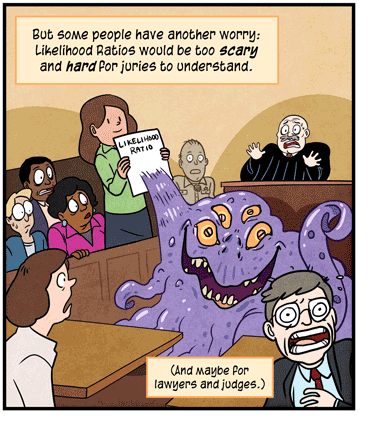

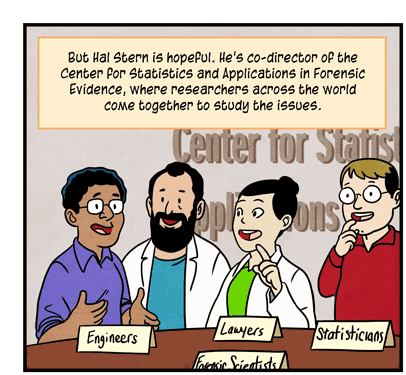

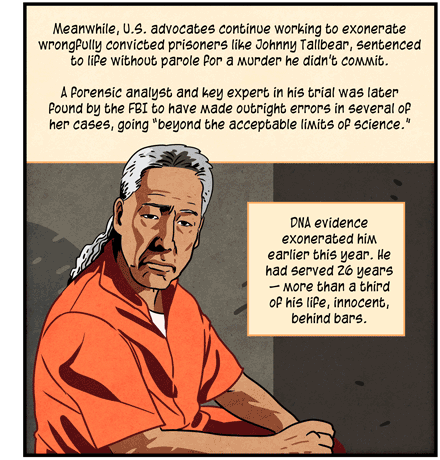

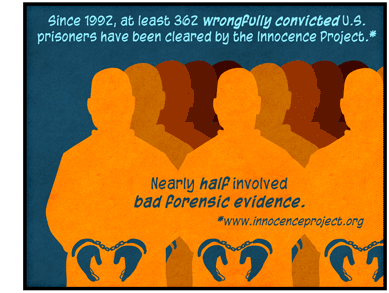

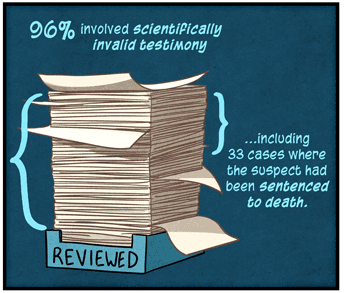

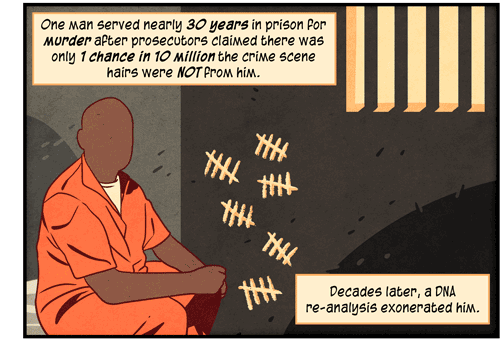

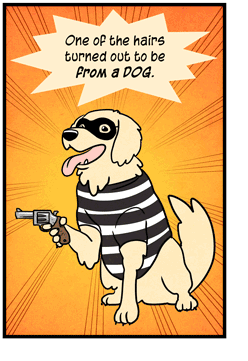

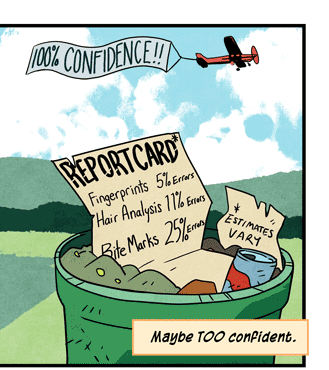

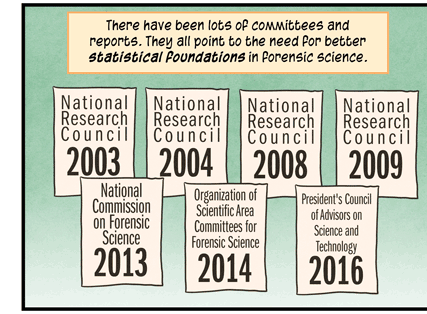

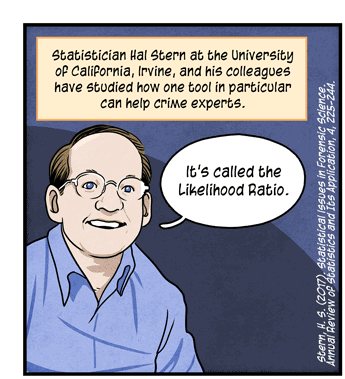

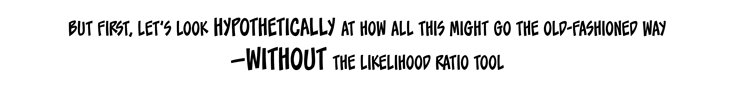

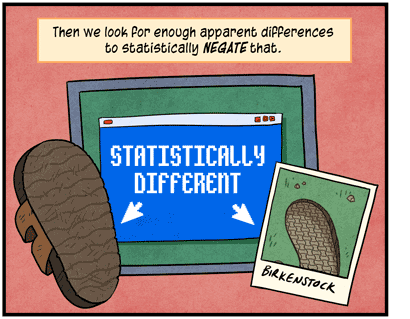

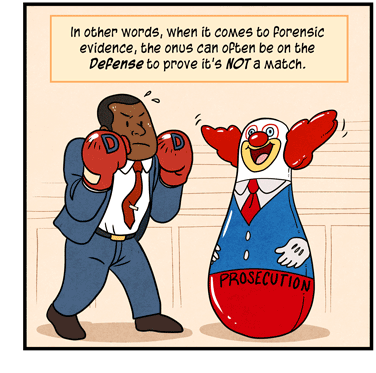

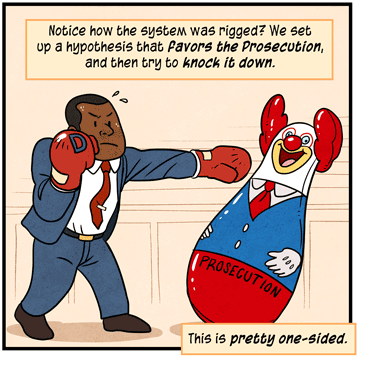

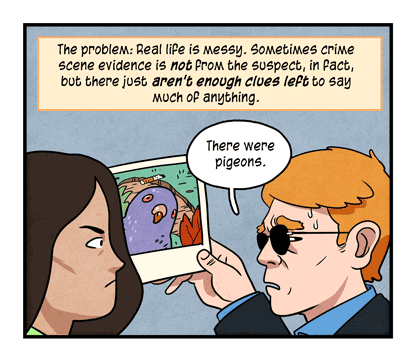

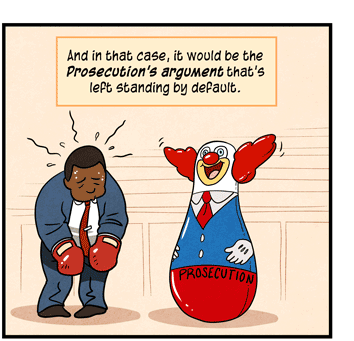

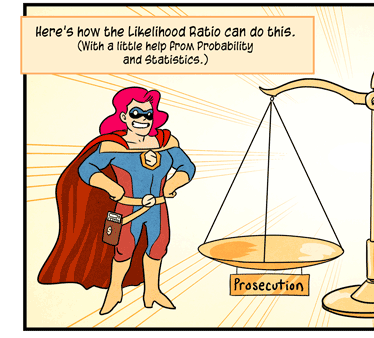

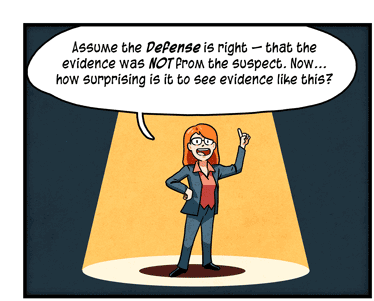

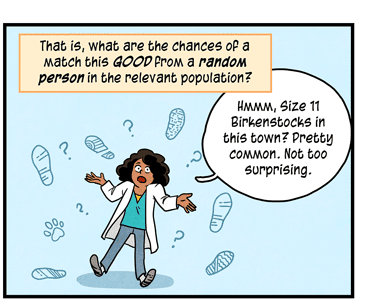

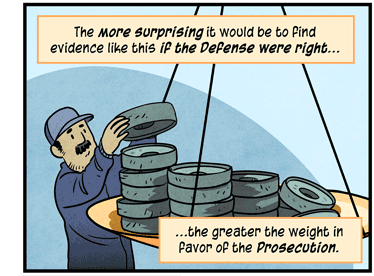

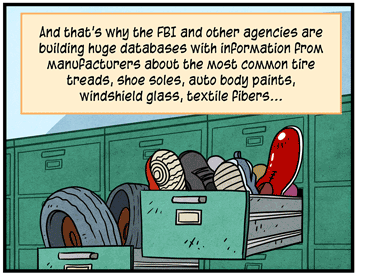

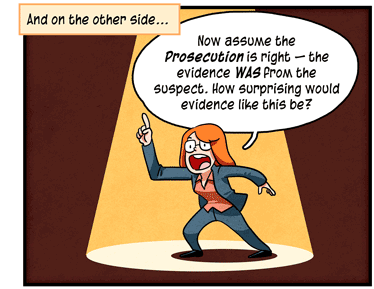

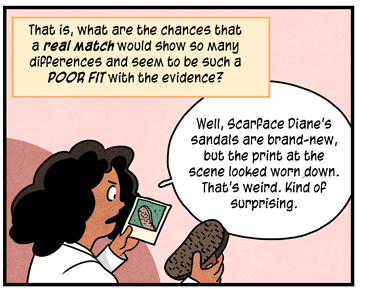

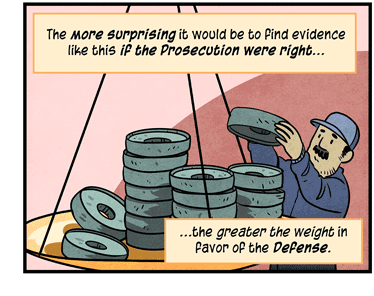

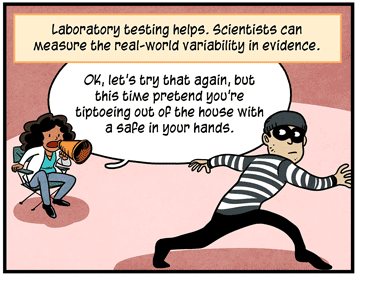

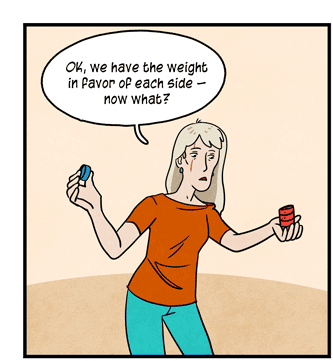

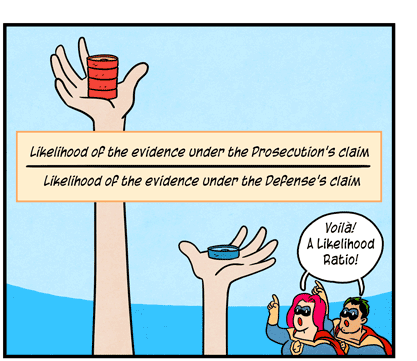

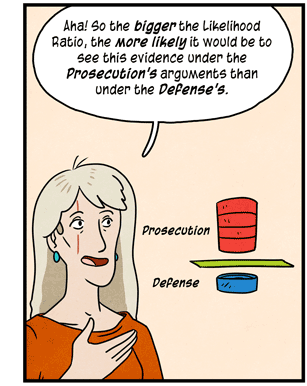

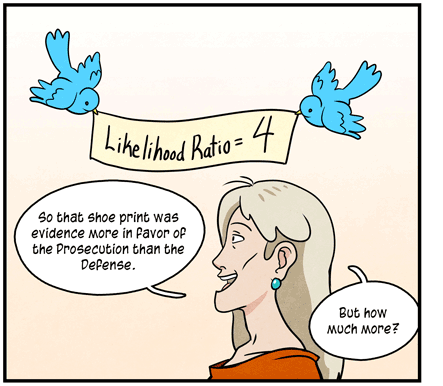

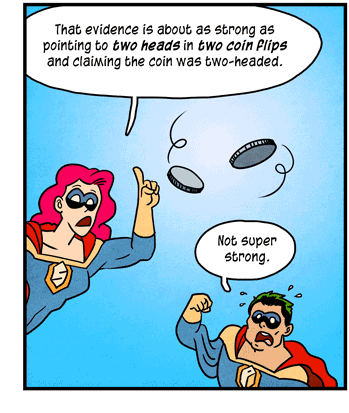

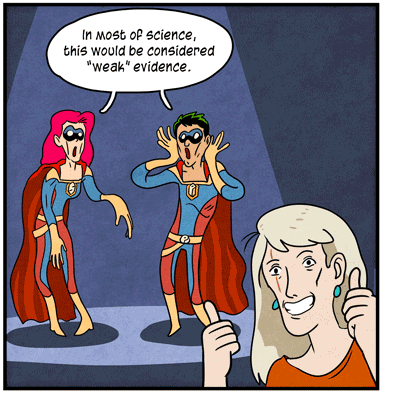

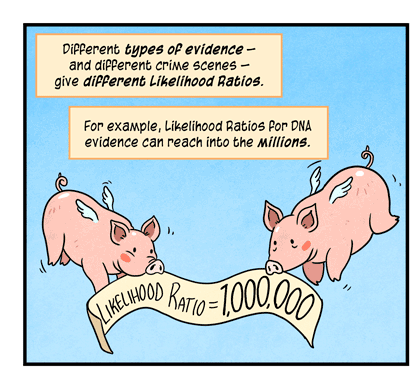

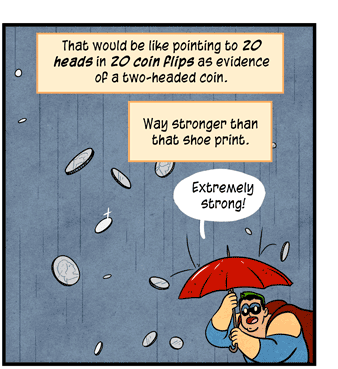

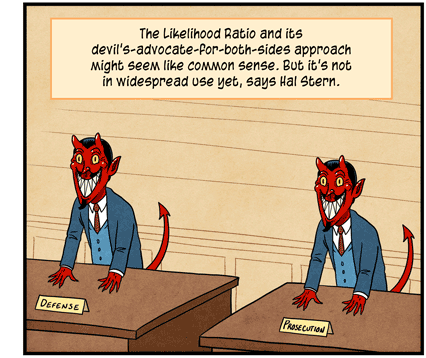

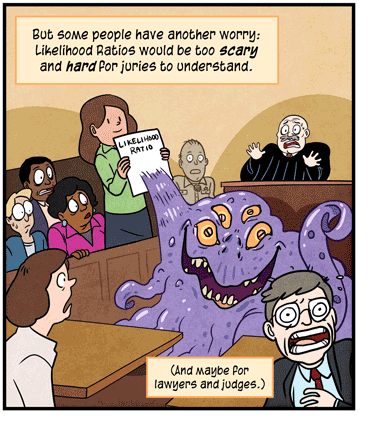

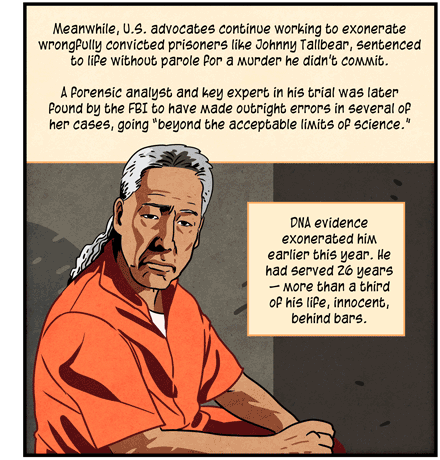

COMIC: Bite marks, shoe prints, crime-scene fibers: Matches to suspects are often far shakier than courtroom experts claim. Better statistical methods — among them, a little beast known as the “likelihood ratio” — can cut down on wrong convictions.

Support sound science and smart stories

Help us make scientific knowledge accessible to all

Donate today

10.1146/knowable-101118-4

Maki Naro is an award-winning feral cartoonist and science communicator. You can reliably find him online, where he tweets from the handle @sciencecomic

TAKE A DEEPER DIVE | Explore Related Scholarly Articles

A free email course on the science of adolescent brain development

Thank you for your interest in republishing! This HTML is pre-formatted to adhere to our guidelines, which include: Crediting both the author and Knowable Magazine; preserving all hyperlinks; including the canonical link to the original article in the article metadata. Article text (including the headline) may not be edited without prior permission from Knowable Magazine staff. Photographs and illustrations are not included in this license. Please see our full guidelines for more information.