The killing of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis shook the nation and set off massive protests around the world over the last few months — putting unprecedented attention on racial bias in law enforcement. For Phillip Atiba Goff, a social psychologist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, the tragedy hit especially close to home.

A Black man in a historically white field, Goff has been using every tool at his disposal — research, data and personal persuasion — for well over a decade now, to prevent unequal and unjust treatment of minorities at the hands of police. He has personally worked with police departments in dozens of US cities, including Minneapolis. The knee on Floyd’s neck and the acts of police violence in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and elsewhere served as sobering reminders that his work was far from over. “This is what I do with my life,” he says. “The goal is fewer dead Black people and fewer Black folks in the hospital.”

Goff is the cofounder and CEO of the Center for Policing Equity (CPE), a national coalition of criminal justice scholars, law professors and former police officers. Part research hub, part advocacy organization and part boots-on-the-ground reform squad, the CPE is in the middle of one of society’s most pressing issues. By some estimates, police kill about 1,000 people annually, and those deaths aren’t evenly distributed. Black men are about 2.5 times more likely than white men to die at the hands of the police, according to a 2019 analysis in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Phillip Atiba Goff, CEO and cofounder of the Center for Policing Equity, works to reduce police mistreatment of minorities.

CREDIT: CENTER FOR POLICING EQUITY

To understand police behavior, Goff and his colleagues combine real-world data with insights from the fields of social psychology and criminal justice. The CPE, founded in Los Angeles and now based at Yale, has worked directly with more than 60 police departments across the country to help them evaluate — and in some cases, radically adjust — their treatment of African Americans and other people of color. Invariably, its investigations show room for improvement. A 2016 CPE report on combined findings from 12 departments around the country found that Black citizens were more than 3.5 times more likely than white citizens to be subjected to police force, ranging from bodily contact to pepper spray to shootings.

“I tell chiefs we’re going to find disparities no matter what they’re doing because disparities exist in everything we do in this country,” says Krista Dunn, a former deputy police chief in Salt Lake City who is now the CPE’s senior director of law enforcement relations. “They have to be able to accept that if they want to work with us. The science is the science.”

A few police chiefs have given Goff a nickname: “Dr. Racism.” For him, it’s a badge of honor. He was one of the first scholars to acknowledge that the unequal treatment of minorities at the hands of police was a problem worth studying. “We have people who have spent their entire lives studying policing and crime,” he says. “When you ask them about race, they say, ‘I don’t have anything interesting to say about race.’ That’s not just an indictment of the data. That’s an indictment of the field and the people in it.”

Goff brought something new to the study of criminal justice partly because he himself was something new, says Kevin Drakulich, a criminal justice researcher at Northeastern University in Boston. “There’s a real benefit to a diversity of perspectives that expands the kinds of questions we ask.”

Growing up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, Goff says he learned quickly that some cops seemed to have it in for Black people. “I figured there were some good cops and some bigots,” he says. As a scholar, he looks beyond those simple descriptions to explore the root causes of excessive force against minorities. As he and his coauthors describe in the Annual Review of Law and Social Science, cops who are inexperienced, under-trained, unsupervised and stressed out are the most likely to lash out at vulnerable people.

Goff’s embrace of data and research undoubtedly changed policing, says David Harris, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh and the author of A City Divided: Race, Fear and the Law in Police Confrontations (Anthem Press, 2020). “The Center for Policing Equity has been one of the most impactful organizations for police reform,” he says. “The sheer force of [Goff’s] charisma and personality, along with [CPE cofounder] Tracie Keesee, got a whole bunch of police departments to sign up for their approach.” The police, Harris says, deserve some of the credit. “A generation of leaders coming to the top are saying, ‘We see we have problems. Maybe we should allow researchers to work with us.’”

Indeed, Goff doesn’t have to file lawsuits or otherwise push to investigate police departments. Chiefs invite him to investigate their departments’ arrest records, use of force and overall engagement with minorities. Some chiefs, Goff says, are already aware that they have serious issues within their ranks. “They tell me behind closed doors that they have some bigoted officers,” he says. “And they have new officers who never should have made it out of the academy. They want me to solve the problem.”

But Goff says his focus isn’t on erasing racist attitudes. Instead, he tries to understand the law enforcement culture, policies and practices that can turn bias into action. “I really don’t care what kind of internal attitude you’ve got, as long as it never becomes a behavior,” he says. Besides, he adds, accusations of racism can backfire. A 2019 survey of 784 police officers conducted by Goff and colleagues found that cops who were concerned about being labeled racist or having their legitimacy questioned were also more likely to endorse violence and coercion against civilians. The authors concluded that officers who feel negatively stereotyped are apt to use violence to regain a sense of control.

The CPE has addressed a variety of policing issues at departments across the United States, including these notable examples.

The best way to prevent the racist behavior of police officers is to avoid the type of situations that can bring them to light in the first place, Goff and his colleagues say. The CPE’s investigations have found that potential triggers can vary from place to place: too many high-adrenaline foot pursuits in Las Vegas, too many encounters with mentally ill people in Seattle, too much immigration enforcement in Salt Lake City. “American policing is hyper-local,” Harris says. “You can’t expect the Department of Justice to just tell all the police departments to take one approach.” In his view, the CPE’s city-by-city method is the best — though not a perfect — way to understand and address the issues.

Police chiefs who reach out to the CPE are eager to understand what’s going on in their own departments, Dunn says. “They always tell me that they can’t fix what they don’t know.” The data are often scattershot and shoddy, but CPE’s experts can still spot important trends. A 2016 review of the Austin Police Department in Texas, for example, found that Black drivers were about four times more likely than white drivers to be pulled over and arrested. Officers used force against Black people at a rate roughly three times higher than Hispanics and six times higher than whites. (A spokesperson for the department declined to comment.)

In California, the Berkeley Police Department invited the CPE to investigate its force in 2015. “We had years of data but no robust analysis,” says Berkeley Police Chief Andrew Greenwood, who was a captain at the time. “CPE has always been interested in looking at science and data to understand what’s going on and how best to police. It’s a big task.”

The CPE’s Berkeley report, published in 2018, found that Black drivers were 6.5 times more likely than white drivers to be pulled over by the police. Once stopped, Black drivers were four times more likely to be searched. However, once police search a vehicle, white drivers were about twice as likely as Black drivers to be arrested, suggesting that the bar was lower for pulling over Blacks than whites. “There’s something going on there,” Dunn says. “But we don’t know why they were stopped. It warrants further investigation.”

In a study by the Center for Policing Equity, Black and Hispanic drivers in Berkeley were more likely than white drivers to be pulled over. (Rates were calculated based on Berkeley Census data; the demographics of people driving through the city may differ, the report noted.)

The report caused a bit of a stir in Berkeley, but there are no hard feelings. “Goff is a good dude,” Greenwood says. “He reached out to me with some nice encouraging words the night of the George Floyd riots.” The respect between the CPE and the Berkeley department goes both ways. Greenwood is the “cream of the crop,” says Dunn, who led the CPE’s Berkeley investigation. “He has been 100 percent committed since Day One.” The relationship continues, and the CPE plans to complete a new report on Berkeley next year.

Greenwood does have some quibbles with the 2018 report: He notes that the calculations were based on Census data for Berkeley itself, which is less diverse than the surrounding area and the tens of thousands of people who pass through each day. Still, he took the results seriously. He says that the Berkeley Police Department is ramping up efforts to better understand racial disparities, including the outsized rates of pulling over Black drivers. Among other things, the department plans to start collecting data on the perceived race of a driver before a stop.

The CPE report on the Berkeley department found relatively few instances of force used against anyone of any race: There were 14 documented blasts of pepper spray and 28 swings of a baton from 2012 to 2016. Notably, until one event in July, Berkeley police hadn’t fired a single shot at a suspect since 2012. (No one was injured in the recent shooting.) “Their use of force is really low,” Dunn says. “It’s a testament to their training, their policies and their culture.”

The department has high standards: It requires new officers to have at least two years’ worth of college coursework in police science, psychology or a related field. Once hired, officers undergo crisis-intervention training that teaches how to de-escalate situations before they get too heated. As an extra layer of supervision, Greenwood says he reviews all body-cam footage after any use of force.

Body cameras and cell phone videos have definitely brought some bad behaviors to light, Goff says. But videos have their limits, as the CPE and others have found. A 2019 randomized control study involving more than 2,200 police offers in Washington, DC, reported that wearing a body camera didn’t meaningfully change behavior, including the use of force, over seven months or more. And a 2015 survey of Black Baltimore residents by members of CPE found that body cameras did little to improve trust in the police. Many residents felt traumatized after seeing video of encounters that ended in death and violence, the report found, especially when police were never punished.

De-escalation training, patience and supervision — the practices and approaches that seem to be working in Berkeley — could go a long way toward improving the cultures of police departments across the country, Goff says. “When we can direct behaviors, we’re removing discretion, and we’re reducing the number of decisions you have to make.” The goal, he adds, “is to create human management systems that short-circuit or interrupt the risk factors for engaging in discriminatory behaviors.”

Any attempt to rid a person — or a department — of bias would likely fail, says Kimberly Kahn, a social psychologist at Portland State University who has collaborated with Goff on several studies. She notes that racial-sensitivity training programs, popular with departments throughout the country, have never been shown to change behavior dramatically. “It’s a good step, but there’s no training that magically takes away these biases,” she says. “They are so ingrained.” (Anyone can explore their own implicit biases with this online test developed by Harvard researchers.)

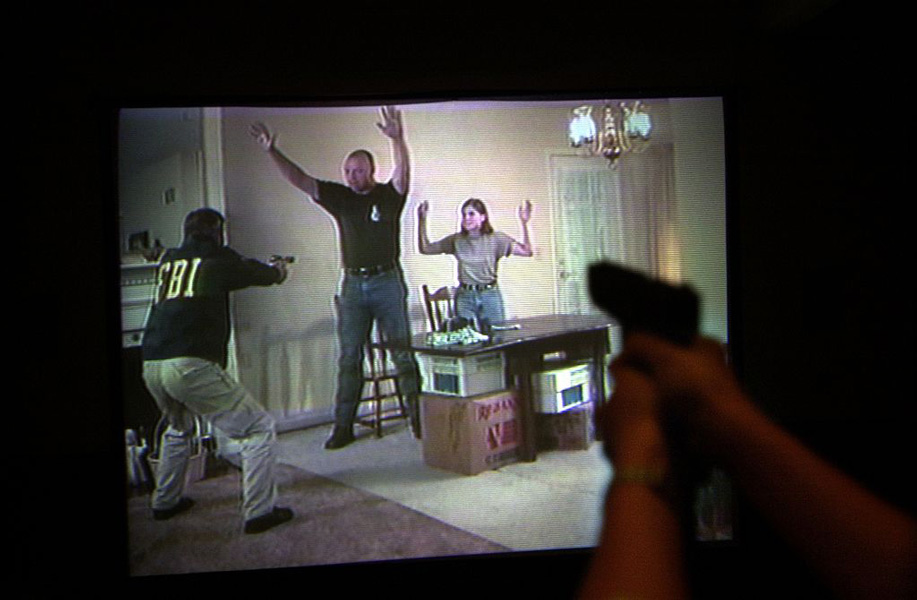

Over the years, Kahn and other researchers have conducted video-game-like shooting simulations that consistently show participants — both police officers and civilians — are generally quicker to pull the trigger when confronted with a Black face. They are, for example, more likely to mistake a wallet or a cellphone for a gun if it’s held by a Black man, and the darker the face, the greater the fear and the greater the chance for mistakes.

Though bias may run deep, biased actions can be minimized through practice and training, research suggests. A 2005 study of 50 police officers in Florida found that they were more likely to “shoot” unarmed Black men than white men in a simulation, but that bias faded after repeated practice with the program. Experienced cops also tend to show more restraint in the streets. A 2004 study of a police department in Southern California found that officers aged over 40 with more than five years of experience are less than half as likely as younger, relatively inexperienced cops to be investigated for excessive force.

In shooting simulations similar to this one used in an FBI training exercise, participants are generally quicker to pull the trigger on Black people, including those who are unarmed.

CREDIT: PHOTO BY DAVID MCNEW / GETTY IMAGES

To better understand the big picture, Goff and colleagues at the CPE are compiling statistics from their investigations into a National Justice Database. As more data come in, police departments could see how they stack up and where they need to improve. With no federal database that tracks use of force or even fatalities, such comparisons are now difficult. By showing chiefs the reality of racial disparities in their own ranks, the CPE is laying the groundwork for reform, Harris says. “When we look back in 10 or 20 years, we’ll see the center as one of those places where new thinking and new leadership began to take hold, even if there were some colossal failures along the way.”

After all of his work — the scholarly research, the data deep dives, the hours of conversation with police chiefs and officers — Goff said the death of George Floyd was a “gut punch.” The location, Minneapolis, only added to the pain. Goff and his team had visited the Minneapolis Police Department in 2015, and for a while it seemed like a success story. With input from the CPE, the city had provided more social workers to engage with the homeless and the mentally ill, leaving the police to other tasks. Goff discussed the Minneapolis experience in a 2019 TED Talk titled “How We Can Make Racism a Solvable Problem — and Improve Policing” that has been viewed more than 2 million times.

In Minneapolis, “we made real changes, not just in the policy and training but in the culture,” Goff says. That progress clearly wasn’t enough to save Floyd or erase bias-driven behavior in the department. A New York Times analysis found that, in the years since the CPE intervention in 2015, Minneapolis police were at least seven times more likely to use force during encounters with Black citizens than with white citizens. “Nobody who does this work ever feels that it’s sufficient to address the scale of the problem,” Goff says. “You have to fail every day, and you get up and try to do it better the next day.”

The days ahead look promising. In the wake of the Floyd killing, Dunn says that she has received a flurry of queries from police departments seeking help. And in recent months, the CPE has received several large donations to support its work, including $1 million each from YouTube and Reed Hastings, the founder of Netflix.

More important, Goff says the protests led by Black Lives Matter and other activist groups — over Floyd’s death and the shootings of other Black Americans like Breonna Taylor and Jacob Blake — have sharpened the focus on the racially problematic history of policing in the US, forcing departments everywhere to think about new approaches. And the CPE will be there to help show the way. “If there’s ever a new world where we can reimagine how public safety looks,” Goff says, “it will be because the protests made us do it.”

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story stated that Phillip Atiba Goff was affiliated with John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City, where the Center for Policing Equity was also based. Prior to the publication of this article, Goff left John Jay for a position at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Center for Policing Equity is now based there too.

Editor's note: The article has also been updated to note Goff’s formal title with the CPE: Goff is CEO, not director.