Last spring, things looked grim for Dora Herrera. Revenues at her family’s 44-year-old restaurant business, Yuca’s, had plummeted within a few short weeks as Covid-19 kept customers away from its two popular taco shacks, in Los Angeles and Pasadena, California.

The drop was precipitous. By late April things reached “a point where we were like, if we don’t get more customers or cash, we’re going to close on Monday,” she recalls.

A federal loan arrived in early May, providing enough money for eight weeks of payroll, she says. In the months that followed, additional loans and grants — and Yuca’s ability to adapt to pandemic restrictions — kept the business alive, though the stress remained.

“We always said, we’ll figure out how to pay that loan back later,” Herrera says. “It was, just stay alive. Just stay alive.”

America’s small businesses play a central role in the nation’s economy and culture. According to a fact sheet released in June by the US Small Business Administration, there were 31.7 million small businesses in the US in 2017, and they employed 60.6 million people — nearly half of American employees. Small businesses created 1.6 million additional jobs in 2019. They generated 32 percent of the nation’s exports in 2018.

It’s understandable, then, that business leaders, policymakers and regular folks have worried a lot about Covid’s impact on mom-and-pop businesses. But a surprising number of these outfits, like Yuca’s, seem to be hanging on. Thus far, it seems, Covid is packing a punch, not a knockout. Rather than wiping everyone out, the pandemic is creating winners and losers.

Definitively quantifying Covid’s impact is difficult: There’s no centralized way to track small-business failures in the US. Many researchers rely on survey data, from the Census Bureau and elsewhere — with findings that often aren’t clear.

Michael Powe, director of research for Main Street America, a Chicago-based nonprofit that works with local partners to revitalize downtown districts throughout the United States, conducted a survey of nearly 6,000 small businesses in late March and early April. It showed that almost 80 percent had closed for some period of time in the first weeks of the pandemic, and that entrepreneurs needed help. The data suggested that around 7.5 million American small businesses would close by the fall of 2020.

But that didn’t happen. Survey data that Powe collected in August showed that less than 10 percent of the businesses he expected to shut down reported having done so. Did things look rosy because owners of failed ventures weren’t inclined to answer surveys? Were stressed entrepreneurs leaning on savings, credit card debt and retirement accounts to avoid officially closing up shop?

Figuring out what might be going on is vital. Because small business is so important, its stumbles stoke the economic woes that Americans face today. Unemployment has reached record levels during Covid, and without federal government assistance, many expect a devastating drop in tax revenues in the spring — which is likely to result in cuts to public services and programs. A recent analysis by Moody’s Analytics calculated that US states might lose $434 billion from their budgets by 2022 because of Covid-related income and sales tax shortfalls.

The US Census Bureau is regularly polling small businesses to track Covid-19’s impact. Many firms report a “moderate negative effect.”

Why small is a big deal

Beyond dollars and cents, researchers and other experts say, small businesses cement communities. Local places like coffee shops become routine gathering places, say sociologists Martha Crowley of North Carolina State University and Kevin Stainback of Purdue University, who have collaborated on studies of local business impacts on towns. And local business creates a virtuous circle, plowing money and resources back into the community. A big-box store might shell out payments to accountants in Arkansas and lawyers in New York, but a small local shop is likely to patronize service providers in the neighborhood. Local businesspeople have a stake in community welfare.

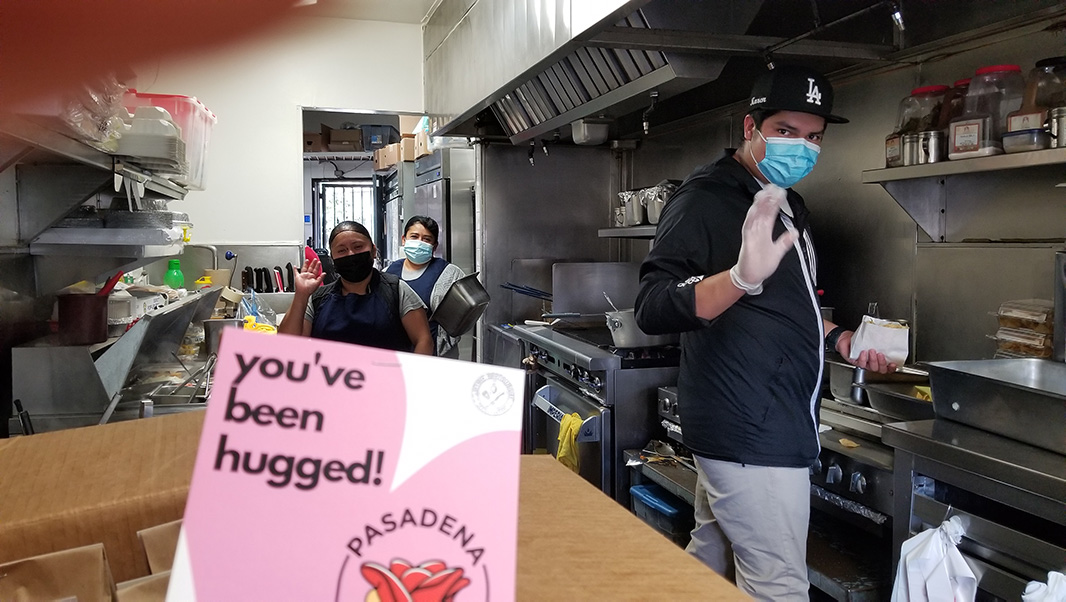

Herrera says that Yuca’s has always been “very community-oriented” — a place where neighbors would walk by and give her mother (who started the business, along with Herrera’s father) “a hundred hugs a day.” When Covid hit, Herrera tried to do her bit to support local business, ordering in from other nearby restaurants and posting about it on social media. She’s doing a lot of networking, and helped to feed essential workers in Pasadena. “A rising tide raises all boats. We’re trying to help ourselves and help others too,” she says.

Such behavior is typical, says Thomas M. Sullivan, a small-business policy expert at the US Chamber of Commerce, which advocates for small businesses. “You will find without exception that the person who is the head of the PTA, the person who is running Girl Scouts, those are all small-business owners,” he says.

That makes small businesses’ struggles a multifaceted reason for worry, as the pandemic drags on and their prospects dim. “Widespread business closure has social costs that extend beyond the obvious losses to owners and workers,” says Charles Tolbert, a sociologist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

CREDIT: DORA HERRERA

Crowley and Stainback explored why in a 2019 review in the Annual Review of Sociology that looked at studies of outcomes in American communities after big-box retailers — and particularly, Walmart, which is more widely studied than other firms — swooped in and wiped out smaller competition. In many places, wages and jobs fell. One study documented “greater increases (or smaller decreases) in family-poverty rates” after Walmarts came to town during the late 1980s and much of the 1990s; another suggested that drops in presidential voting rates, nonprofit activity and church adherence may have also been linked to the demise of local businesses.

When big box stores wiped out mom-and-pop grocers, people began buying less healthy foods, including fewer fruits and vegetables, and obesity rates climbed. Crime rates increased, too — perhaps as a function of neighbors losing walkable main streets, and larger swaths of shoppers flocking instead to vast and often-sparsely-patrolled parking lots.

Losing small businesses rips away at a neighborhood’s fabric, Crowley and Stainback said in an interview with Knowable. And while it took decades for big box stores to wreak havoc on American towns, Stainback notes, Covid-19 may have a similar impact in a matter of months.

Sullivan says that dozens of small business leaders he’s spoken with during the pandemic are intensely worried about their employees’ economic, physical and emotional well-being. They have much cause to worry, says Rachel Doern, a management scholar at Goldsmiths, University of London, who studies how entrepreneurs cope in adverse situations. She fears that small-business closures will amplify “an ever-increasing mental health crisis.” The small-business owners Doern has interviewed in London — her new paper “Knocked down but not out and fighting to go the distance” describes their adjustments in the first months of lockdown — spend a great deal of time dealing with Covid-related employee distress, sometimes to their own detriment.

“Small-business entrepreneurs already do so much, wear so many hats,” she says. “A crisis can double the workload.” If vulnerable small businesses fail, she adds, deprivation and social isolation are likely to increase.

The silver lining

Not all small businesses will fail — for some, Covid presents an opportunity. “Just as some people have succumbed to Covid and others hardly feel ill at all,” says Scott Omelianuk, editor of small-business-focused Inc. magazine, “that applies to the economy as well.”

The pandemic shifts resources from some players to others. Surcharges and tips that used to wind up in the pockets of restaurant servers now go to delivery workers. Retail and other high-touch service businesses like boutiques and hair salons struggle. Tech businesses seem to thrive.

Experts have been surprised by the scope and speed of some firms’ success. Sullivan, of the US Chamber of Commerce, points to data from the Economic Innovation Group, a Washington-based think tank, that suggest the formation of new businesses that are likely to hire employees throughout the second half of 2020 outpaced similar activity in 2019. After the 2008 recession, it took years for this type of hiring activity to resume — the speed this time around, he believes, is a sign that businesses are successfully pivoting and innovating. In a December survey, Powe’s organization found that many communities — particularly in rural areas — reported net increases in businesses. “If we take our survey respondents to be typical of our network of communities, we’re talking about 5,300 business closures and 5,900 business starts over the course of the pandemic thus far,” he estimates.

Entrepreneurs are innovating. Herrera, who used to teach a Christmastime tamale-making class at Yuca’s, moved the lesson online and enrolled 40 people from as far away as Mexico, New York and London. She’s planning another online cooking event that should also attract new customers, she says.

But Sullivan cautions that rather than a “V-shaped recovery,” in which the economy bounces back as quickly as it fell, the US is likely facing a “K-shaped recovery,” where some people and institutions rebound while others suffer ongoing decline. (The shapes of the letters reflect the trendlines.)

Businesspeople and policymakers hope for a “V-shaped” economic recovery, where growth bounces back as quickly as it fell, across the board. The post-pandemic recovery may be “K-shaped” — with some businesses thriving while others fail.

“There’s some cause for optimism, but it’s not productive to say to struggling small business owners, ‘You’re going to go bankrupt, but look at all of these new innovators that are kicking butt!’” he says. “Congress has to take action to address the K.”

Securing aid for struggling businesses has been difficult throughout the Covid crisis. In late March, Congress passed the $2.2 trillion CARES Act, which authorized $659 billion for Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans to help small businesses meet payroll and other expenses. The $900 billion stimulus package passed in December extended the PPP program and other benefits, and the incoming Biden administration proposed billions more for small business in its $1.9 trillion stimulus proposal floated in January. Some states have offered loans and tax rebates to keep companies afloat, but they lack the deep pockets of the federal government.

Society may have to grapple with many kinds of broad change once the Covid economy’s winners and losers become clear. Omelianuk rejects the notion that the pandemic will kill off big cities, but if managers and workers decide they want to stick with remote workplace setups, some are beginning to wonder if it is time to convert Manhattan’s corporate office space into apartments.

How such a shift would play out on the more modest streets and neighborhoods where America’s small businesses call the shots worries Powe. He is heartened that, with the exception of his kids’ beloved local toy store, most places in his Seattle neighborhood seem to still be in business. Work has shifted online; delivery service has replaced in-store shopping.

Still, he says he is “befuddled” by some of the more optimistic data he’s seen thus far. Things seem very quiet when he walks down his street.

“The nightmare scenario is that Amazon and Walmart and Target are the three retailers that do most of the retail trade across the country,” he says, adding that he doubts anyone in small towns — or big cities — wants to hand all commerce to a handful of giant companies and lose local flavor. “This could be really dramatic in terms of what it can do for place identity and feel of communities.”

Herrera, for her part, is trying to figure out if Yuca’s will need another federal loan, but she expects to stay in business — and believes that some of the changes Covid has wrought, such as Zoom networking events and meetings, have only brought her closer to her neighbors, and to other restaurateurs in LA.

“We’re all in this, and we’re doing it together,” she says.

A version of this article appeared earlier in the Los Angeles Times.

This article is part of Reset: The Science of Crisis & Recovery, an ongoing series exploring how the world is navigating the coronavirus pandemic, its consequences and the way forward. Reset is supported by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.