Katherine Flegal wanted to be an archaeologist. But it was the 1960s, and Flegal, an anthropology major at the University of California, Berkeley, couldn’t see a clear path to this profession at a time when nearly all the summer archaeology field schools admitted only men. “The accepted wisdom among female archaeology students was that there was just one sure way for a woman to become an archaeologist: marry one,” Flegal wrote in a career retrospective published in the 2022 Annual Review of Nutrition.

And so Flegal set her archaeology aspirations aside and paved her own path, ultimately serving nearly 30 years as an epidemiologist at the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), part of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There, she spent decades crunching numbers to describe the health of the nation’s people, especially as it related to body size, until she retired from the agency in 2016. At the time of her retirement, her work had been cited in 143,000 books and articles.

In the 1990s, Flegal and her CDC colleagues published some of the first reports of a national increase in the proportion of people categorized as overweight based on body mass index (BMI), a ratio of weight and height. The upward trend in BMI alarmed public health officials and eventually came to be called the “obesity epidemic.” But when Flegal, along with other senior government scientists, published estimates on how BMI related to mortality — reporting that being overweight was associated with a lower death rate than having a “normal” BMI — she became the subject of intense criticism and attacks.

Flegal and her coauthors were not the first to publish this seemingly counterintuitive observation, but they were among the most prominent. Some researchers in the field, particularly from the Harvard School of Public Health, argued that the findings would detract from the public health message that excess body fat was hazardous, and they took issue with some of the study’s methods. Flegal’s group responded with several subsequent publications reporting that the suggested methodological adjustments didn’t change their findings.

The question of how BMI relates to mortality, and where on the BMI scale the lowest risk lies, has remained a subject of scientific debate, with additional analyses often being followed by multiple Letters to the Editor protesting the methods or interpretation. It’s clear that carrying excess fat can increase the risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes and some types of cancers, but Flegal’s work cautioned against tidy assumptions about the complex relationship between body size, health and mortality.

Katherine Flegal dreamed of becoming an archaeologist but saw few opportunities for women in the field. Instead, she studied nutrition and became an epidemiologist. Flegal (middle) works with fellow students at an archaeological dig site in Moravia, Czechoslovakia, in 1964.

CREDIT: COURTESY OF KATHERINE FLEGAL

Flegal spoke with Knowable Magazine about her career, including some of the difficulties she faced as a woman in science and as a researcher publishing results that ran counter to prevailing public health narratives. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

After finishing your undergraduate degree in 1967, one of your first jobs was as a computer programmer at the Alameda County Data Processing Center in California, where you handled data related to the food stamp program. What drew you to that job?

It’s kind of hard to even reconstruct those days. This was well before what I call the “toys for boys” era, when people had little computers in their houses, and you might learn how to write a program in BASIC or something. You didn’t learn how to program in school at all. Big places like banks had started using computers, but they didn’t have people who knew what to do with them. So they hired on the basis of aptitude tests, and then they trained you.

I realized if you could get a job as a trainee, they would teach you how to program, which was a pretty good deal. So I applied for a couple of these jobs and took my aptitude tests and scored very highly on them. I was hired as a programmer trainee, and they spent six months training us. It was not just like “press this button, press that button.” We really got a very thorough introduction.

At that time, there was gender equality in programming, because it was based just on aptitude. In my little cohort, there were two women and three men, and everybody did the same thing. It was very egalitarian. Nothing really mattered as long as you could carry out the functions and get everything right.

And that was different from some of the other jobs available at that time?

Yeah, there were “Help Wanted — Women” and “Help Wanted — Men” ads, and the “Help Wanted — Women” ads were secretarial or clerical or something like that. It was very clear that you weren’t supposed to be applying for these other jobs. There were the kinds of jobs that men got and the kinds of jobs that women got.

When Flegal first entered the job market, employment ads commonly specified whether they were hiring men or women, and opportunities for women were often limited.

CREDIT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

What else did you learn in that position as a programmer?

This was a governmental operation, with legal requirements and money involved. It was our job to track everything and test every program very, very carefully. If later you found an error lurking in a program, you had to go back and rerun everything. We were taught to do everything just right — period. And that was a pretty valuable lesson to learn.

It was very well-paid, but we had valuable skills, and we had to work a lot of overtime. They would call you up in the middle of the night if something was flagged in your program. I got to be quite a good programmer, and that really stood me in good stead.

Why did you decide to go to graduate school to study nutrition?

My job was OK, but I didn’t have a lot of autonomy, and I think I didn’t like that very much. I thought it would be interesting to study nutrition. I think unconsciously I was selecting something that was more girly in some way.

After completing your PhD and a postdoc, you struggled to find a secure university job. You wrote about how you think that the “Matilda Effect” — a term coined by science historian Margaret Rossiter to describe the systematic under-recognition of women in science — contributed to your being overlooked for academic jobs. Can you tell us more about that?

Women don’t get recognized and are much more likely to just be ignored. I didn’t think this was going to be an issue, but looking back, I realized that gender played much more of a role in my career than I had thought.

You can’t really put your finger on it, but I think you just are not viewed or treated in the same way. I put this anecdote at the beginning of my Annual Review article: My husband and I are at the holiday party for the University of Michigan biostatistics department that I work in. There’s a professor there who has no idea who I am, although this is a very small department and I walk by his office all the time. He sees my husband, who looks reasonably professional, and asks the department chair who he is. When he’s told, “That’s Katherine Flegal’s husband,” he responds, “Who’s Katherine Flegal?” It was like I was just part of the furniture, but my husband was noticed.

How did you end up working as an epidemiologist at the CDC?

A CDC scientist came to Michigan and was recruiting. She encouraged me and other people — I wasn’t the only one by a long shot — to apply for these various jobs. I applied and then kind of forgot about the whole thing, but then this offer came through. It wasn’t really what I had in mind, but it was an offer, so I accepted it.

It sounds like you didn’t expect that to turn into a 30-year career in the federal government.

I certainly didn’t.

Since the early 1960s, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey has collected data about body size and health from a nationally representative sample of people in the United States. Mobile trailers travel to study sites to collect data from participants.

CREDIT: CDC

What was different about working at the CDC compared with academia?

It has its good and bad aspects, like most things do. You work for an organization, and you have to do things to meet the organization’s needs or requirements, and that can be frustrating. We didn’t have to apply for grants, so that was good in one way and bad in another. There was no ability to get staff or more resources. You just had to figure out what to do on your own.

The advantage was that it was a really secure job, and we produced a lot of data. NCHS, the part of CDC that I worked in, is a statistical agency. It’s not agenda-driven, which was good.

On the other hand, what you write has to be reviewed internally, within the CDC, and it’s a tight review. If the reviewers say, “I don’t like this,” you either have to convince them it’s OK, or do what they say. You cannot submit your article for publication until you satisfy the reviewers.

What kinds of projects did you work on at the CDC?

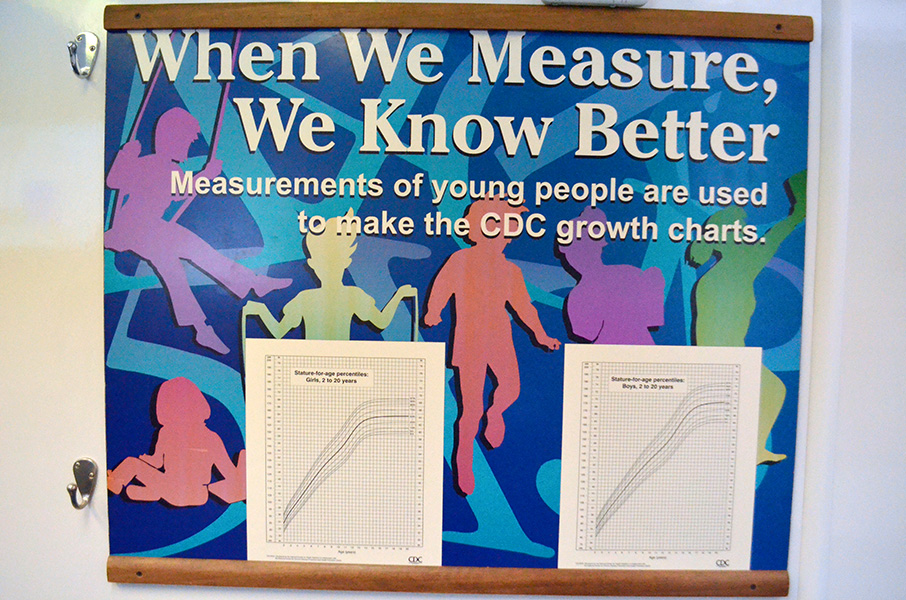

I worked for the NHANES program, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. I would think of different projects to analyze and make sense of the survey data. But if somebody wanted me to do something else, I had to do something else. For example, I got assigned to deal with digitizing X-rays endlessly for several years. And I worked on updating the childhood growth charts used to monitor the growth of children in pediatricians’ offices, which turned out to be surprisingly controversial.

A poster displayed in an NHANES mobile trailer shows the CDC’s growth charts, which are used by pediatricians, nurses and parents to monitor the growth of children.

CREDIT: CDC FOUNDATION

Can you tell us more about what NHANES is, and why it’s important?

NHANES is an examination survey, so there are mobile units that go around the country and collect very detailed information from people; it’s like a four-hour examination. When you read about things like the average blood cholesterol in the United States, that kind of information almost always comes from NHANES, because it’s a carefully planned, nationally representative study of the US population. It started in the early 1960s, and it’s still running today.

One of the things that distinguishes NHANES from other data sources is that it directly measures things like height and weight, rather than just asking people about their body size. Why does that matter?

People don’t necessarily report their weight and height correctly for a variety of reasons, not all of which are fully understood. There’s a tendency to overestimate height; there’s kind of a social desirability aspect probably involved in this. And there’s a tendency for people, especially women, to underreport their weight a little bit. Maybe they’re thinking “I’m going to lose five pounds,” or “This is my aspirational weight,” or they don’t really know, because they don’t weigh themselves.

That can make a difference — not huge, but enough to make quite a difference in some studies. And what you don’t know is whether the factors that are causing the misreporting are the same factors that are affecting the outcome. That’s very important and overlooked. It’s a risky business to just use self-reported data.

One of the first studies you coauthored related to obesity was published in JAMA in 1994 and described an increase in BMI among adults in the US.

Right. I was the one who said that we at NCHS needed to publish this, because we produced the data. We were really astonished to get the results, which showed that the prevalence of overweight BMI was going up, which is not what anybody expected, including us.

Flegal and her colleagues at the CDC were among the first to publish data showing a national increase in the percentage of people in the US who were overweight, beginning in the 1980s. This graph is adapted from their 1994 paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Did you face pushback from within the CDC for some of the things that you were publishing?

Yes. This really started in 2005, when we wrote an article estimating deaths associated with obesity. The CDC itself had just published a similar article the year before with the CDC director as an author, which is fairly unusual. That paper said that obesity was associated with almost 500,000 deaths in the US and was poised to overtake smoking as a major cause of death, so it got a lot of attention.

In our paper, we used better statistical methods and better data, because we had nationally representative data from the NHANES, and my two coauthors from the National Cancer Institute were really high-level statisticians. We found that the numbers of deaths related to obesity — that’s a BMI of 30 or above — were nothing as high as they found. But we also found that the overweight BMI category, which is a BMI of 25 up to 29.9, was associated with lower mortality, not higher mortality.

We had this wildly different estimate from what CDC itself had put out the year before, so this was an awkward situation for the agency. The CDC was forced by the press to make a decision about this, and they kind of had to choose our estimates, because they couldn’t defend the previous estimates or find anything wrong with ours. The CDC started using them, but they were tucked away. It was really played down.

In a 2005 study, Flegal and coauthors reported that in several nationally representative NHANES surveys, a BMI classified as overweight (BMI of 25 to less than 30) was associated with fewer deaths relative to normal BMI (18.5 to less than 25). Both underweight (BMI less than 18.5) and obesity (BMI more than 30) correlated with greater mortality. The result ran counter to public health messaging and led to intense criticism of Flegal’s work.

That study generated a lot of media attention and criticism from other researchers. Was that a surprise to you?

Yes, that was completely a surprise. There was so much media attention immediately. I had to have a separate phone line just for calls from journalists. And almost immediately, the Harvard School of Public Health had a symposium about our work, and they invited me, but they didn’t offer to pay my way. CDC said that they didn’t want me to go, so that was the end of that. But the final lineup they had was other people saying how our findings didn’t agree with theirs, so this whole symposium was basically an attack on our work.

You and coauthors also published a meta-analysis of 97 studies in 2013 that found that being overweight or mildly obese wasn’t associated with a greater risk of mortality. Did you face a similar response to that article?

We embarked on a systematic review and found that these results pretty much agreed with what we had already found. We published that, and there was a lot of criticism, another symposium at Harvard, and just a lot of attacks. The chair of Harvard’s nutrition department, Walter Willett, went on NPR and said that our paper was so bad that nobody should ever read it, which is a pretty unusual thing for a scientist to be saying.

That must have been difficult to have your work attacked so publicly.

It was really awful, to be honest. I don’t usually admit that. It was extremely stressful. And I didn’t have much support from anywhere. A lot of people thought what we had done was fine, but those people were not writing letters and holding symposia and speaking out in favor of us.

I know my coauthors were a little startled by the way in which I was treated, and they always said, maybe if I had been a man I would not have been treated quite so badly. That could be true, but I don’t have any way of knowing.

Was anyone able to identify anything incorrect about your analysis?

Well, they certainly didn’t identify any specific errors. There was no evidence that we had done anything wrong, and no one has ever found anything specifically that would have made a difference to our results.

There’s a whole school of thought that there are all these confounding factors like smoking and illness. For example, maybe people are sick, and they lose weight because they’re sick, and that will affect your results, so you have to remove those people from your analyses. People raised all these criticisms, and we looked at all of them and published a whole report looking at it every which way. But we didn’t find that these factors made much of a difference to our results.

There are many, many studies of BMI and mortality that tried all these things, like eliminating smokers and people who might have been sick, and it doesn’t make any difference. This is not an uncommon finding.

Among her achievements, Katherine Flegal received the Director’s Award from National Center for Health Statistics, presented by center director Edward Sondik, in 1996.

CREDIT: COURTESY OF KATHERINE FLEGAL

One of the critiques of this research was that it would confuse people or compromise public health messaging. How do you respond to that?

Well, I don’t think it makes sense. I think that when you find a result that you don’t expect, the interesting thing ought to be, how can we look into this in a different way? Not just to say that this is giving the wrong message so it should be suppressed. Because that’s not really science, in my opinion.

Is part of the issue that BMI is not a great proxy for body fatness? Or that the BMI categories are kind of arbitrarily drawn?

Well, they are very arbitrary categories. I think the whole subject is much more poorly understood than people recognize. I mean, what is the definition of obesity? It ended up being defined by BMI, which everybody knows is not a good measure of body fat.

And there’s other research that suggests body fat is not really the issue; maybe it’s your lean body mass, your muscle mass and your fitness in other ways. That could be the case, too. I don’t really know, but that’s an interesting idea. BMI is just so entrenched at this point; it’s like an article of faith.

When you look at how much your work has been cited, and how much influence it had, it seems you had quite an impact.

I think I did, but it really wasn’t what I expected or set out to do. I got into this controversial area pretty much by accident. It caused all this brouhaha, but I don’t back down.

We were all senior government scientists who had already been promoted to the highest level. In a way, it was kind of lucky that I was working for CDC. Writing those articles, it was a career-ending move. If I had had anything that could have been destroyed, somebody would have destroyed it. I think I wouldn’t have gotten any grants. I would have become disgraced.

But this stuff is serious. It’s not easy, and everybody has to decide for themselves: What are they going to stand up for?