The ruin of Aleppo. A desperate flight of refugees across the Mediterranean. Children in battle zones, covered in dust and blood. A handful of images starkly capture the tragedy of the Syrian civil war.

But even before Syria unraveled, other photos showed a slower-moving disaster — one that’s harder to parse, but perhaps more ominous. Parched earth, fallow fields and refugee families huddled near ramshackle tents in the desert told the story of a severe drought that had ravaged the region for three years beginning in the winter of 2006–07. And drought, too often, is a prelude to war.

Prolonged fighting has led to the destruction of many important religious and cultural sites in Syria. In 2013 the famed Great Mosque of Aleppo become one of them.

CREDIT: TASNIM NEWS AGENCY/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

It wasn’t that this drought directly caused the fighting that erupted in Syria in 2011. But it followed on the heels of two other multiyear droughts, in the late 1980s and 1990s. And it worsened conditions already ripe for conflict, such as overcrowded cities where rampant unemployment left large numbers of people idle and with a growing list of grievances.

In turn, humanity’s interference with the global climate, chiefly through the burning of fossil fuels, made it two to three times more likely that a drought as severe as the one that preceded the civil war would occur in the region, researchers concluded in a 2015 study. “The timing was very telling,” says the study’s lead author, Colin Kelley, a climate researcher at Columbia University. “There seemed to be a very clear sequence of events.”

Concerns over a rapidly warming world are spurring scientists to look closely at how climate change might fuel civil conflict, even as foreign policy experts, humanitarian groups and others increasingly worry about regions destabilized by persistent strife — the Middle East being just one. By studying this connection, researchers say they can better predict future risks of collective violence as well as better understand the complex series of events that spawn it. And that may inform efforts to keep the peace.

A canal stemming from the Euphrates river brings water into this dry region of eastern Syria. By 2010, years of drought had wiped out most of the livestock in the region and played a role in driving half a million people to leave the area.

CREDIT: KHALED AL HARIRI

Some climate-strife connections are easy to see: Environmental stressors such as drought can destabilize societies by putting access to water or food at risk, for example, as seen with East Africa’s struggles with famine. But more often, the link between climate and conflict is less direct. Instead, researchers, policymakers and national security experts consider climate change and other environmental disruptions as serious “threat multipliers” — amplifying other forces that lead to large-scale violence, such as armed conflict, genocide and gang warfare.

Scholarship on the relationship between regional climate changes and violent conflict, be they contemporary cases or historical ones, is not of one voice. Every conflict has its own particulars, defying broad-brush conclusions. Yet even with their divergent opinions and case histories, most researchers agree that a warming planet, and the environmental shifts that accompany it, can set the stage for unrest.

Changes ahead

The planet is getting warmer. Average surface temperatures on Earth in 2016 were the warmest since record-keeping began in 1880. Most of the warming seen over the past century has occurred since about 1980; 16 of the 17 warmest years on record have occurred since 2001. As the century progresses and average global temperatures continue to rise, people can expect more hot days and nights, more rain in some areas and more drought in others, and higher sea levels almost everywhere, according to the latest projections from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Infectious diseases carried by insects will spread. The risk of extreme weather events will increase.

The IPCC has asserted that climate change can indirectly increase the risk of violent conflict around the world, echoing military and international relations experts in the United States and abroad. One scenario might go something like this: A drought depletes a region’s water and devastates domestic agriculture, and the life-threatening scarcity of resources leads to violent conflict between nations, or between political factions within a nation.

But proving that has been challenging for researchers trying to disentangle the consequences of climate change — drought, sea level rise, extreme weather — from other factors that can lead to conflict, such as the actions or neglect of an oppressive regime, deep-seated ethnic tensions and longstanding border disputes, says Jonathan Patz, an environmental health scientist at the University of Wisconsin who has studied the health impacts of climate change for more than 20 years.

Looking around the globe at how environmental change affects human relations, Patz cites North Korea’s famine in the late 1990s as just one example of how challenging it can be to connect the dots between cause and effect. “When famine struck North Korea, the question arose of which was most to blame for those who died from malnutrition: the extreme drought conditions or the inflexibility of the government to work with international aid,” Patz says.

How can scholars be confident that collective violence in contemporary times can be attributed to climate change at all? By studying many events in a variety of places, Patz and others say. In the Annual Review of Public Health in 2017, Patz, along with colleagues Barry Levy of Tufts School of Medicine and Victor W. Sidel of Weill Cornell Medical College, review studies of country-specific conflicts as well as broader meta-analyses that look at such studies in aggregate. Overall, the bulk of the evidence supports the idea that climate change has been an important factor in a number of conflicts, they conclude. They also acknowledge, however, that some research has shown only a weak connection between climate change and conflict, including studies of East Africa, Afghanistan and the Sahel in West Africa.

One of the meta-analyses that Patz discusses is a 2014 study by Marshall Burke of Stanford University and UC Berkeley’s Solomon Hsiang and Edward Miguel. They examined 55 studies of climate change and conflict to better define the connection. In their working paper, Climate and Conflict, for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Burke, Hsiang and Miguel concluded that “deviations from moderate temperatures and precipitation patterns systematically increase the risk of conflict, often substantially.” Using the past as a guide, they estimated that warming on the African continent could increase the incidence of armed conflict there by 54 percent — resulting in 393,000 additional battle deaths by 2030.

Climate-conflict hot spots

In recent years, the academic literature has focused on numerous contemporary hot spots for conflict:

- In 2016, Nina von Uexkull from Uppsala University in Sweden and colleagues found that for people dependent on agriculture for subsistence, and for politically excluded groups in very poor countries, a local drought increases the likelihood of sustained violence.

- In 2014, Jean-François Maystadt and Olivier Ecker of the International Food Policy Research Institute concluded that drought in Somalia between 1997 and 2009 led to lower prices for livestock, which fueled conflict.

- In 2012, Francis Opiyo from the University of Nairobi and colleagues acknowledged the complex political, economic and cultural factors that drive violent conflicts in Kenya. But they found also that frequent drought intensified competition for diminished natural resources and helped lead to violent conflict.

A fleet of boats set out to fish around disputed islands in the East China Sea. Fish migrations spurred by a warming ocean could complicate relations in the already heavily contested waters here and in the nearby South China Sea.

CREDIT: PICHI CHUANG/REUTERS PHOTOS

Francesco Femia, cofounder and president of the Center for Climate and Security in Washington, DC, a nonpartisan security and foreign policy institute, adds other trouble spots to the list. He sees the potential for conflicts within fragile states that are vulnerable to climate changes, as well as among individual nations competing for natural resources and territory.

Pakistan, a country grappling with the consequences of climate change, falls in the first group. It is highly dependent on fresh water from glaciers, and this source is diminishing. Meanwhile, the government does not have full control over the country, terrorist groups contribute to instability and a longstanding conflict with India over Kashmir remains unresolved.

Femia sees the South China Sea as another potential trouble spot. As ocean waters warm, fish stocks on which Vietnam depends are migrating northward into contested waters with China. It’s not inconceivable that a conflict between the two nations could draw in the United States.

In the Arctic, where sea ice is diminishing and new sea lanes are opening, tensions between the United States and Russia could begin to play out at the top of the world.

The Syrian disaster

Desperate to escape worsening violence, millions of Syrians have fled since 2011. Thousands of refugees have died trying to get out.

CREDIT: GGIA/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Perhaps no contemporary conflict has evoked such widespread horror as the civil war in Syria. Since it began in 2011, an estimated 400,000 men, women and children have been killed, nearly 5.4 million have fled the country and millions more remain displaced within Syria, according to the United Nations — fueling a refugee crisis on a scale not seen since the Second World War.

Colin Kelley is not the first researcher to examine the connection between drought and the war in Syria, but his 2015 paper clearly explains how environmental change contributed to the onset of war.

Droughts come and go in the Eastern Mediterranean’s Levant region, which encompasses Syria and many of its neighbors. But the 2007–10 drought in Syria was part of an overall drying of the Levant between 1998 and 2012 that was anything but ordinary. Yet it should not have come as a surprise. The climatic changes seen in the region since the mid-2000s in particular fall very much in line with what computer models predict there as humans continue to pump greenhouse gases into the global atmosphere.

“It was a natural drought that occurred, but it was made much worse by climate change,” Kelley says.

Climate scientist Colin Kelley speaks on climate's influence on collective violence.

CREDIT: COURTESY OF C. KELLEY

In 2016, a separate study examining tree-ring records and led by Benjamin Cook of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies concluded that a more expansive drought from 1998 to 2012 in the Levant was the most extreme drying in the past 900 years.

Syria suffered massive losses in agriculture and a spike in food prices, Kelley says. By February 2010, the price of livestock feed had increased 75 percent and nearly all the nation’s herds had died. This was followed by a mass migration of people from rural farming areas to the outskirts of cities, and compounded by a wave of refugees from Iraq. In 2002, 8.9 million people lived in cities in Syria; by the end of 2010 nearly 14 million people did. These overcrowded settlements, lacking infrastructure and plagued with high unemployment and crime, became the heart of unrest in the country.

But that’s not the whole story. The Syrian government’s agriculture policies made Syria more vulnerable to drought than it needed to be, Kelley concludes. Between 1971 and 2000, the government of President Hafez al-Assad took steps to increase agricultural production that included redistributing land, supporting new irrigation projects and setting quotas — all to secure the support of rural residents. But these initiatives “endangered Syria’s water security by exploiting limited land and water resources without regard for sustainability,” Kelley writes.

Over decades Syria depleted its groundwater. The government in 2005 passed a law intended to control the extraction of groundwater, but the law wasn’t enforced. When the drought began in the winter of 2006-07, agriculture in Syria’s breadbasket in the northeast collapsed.

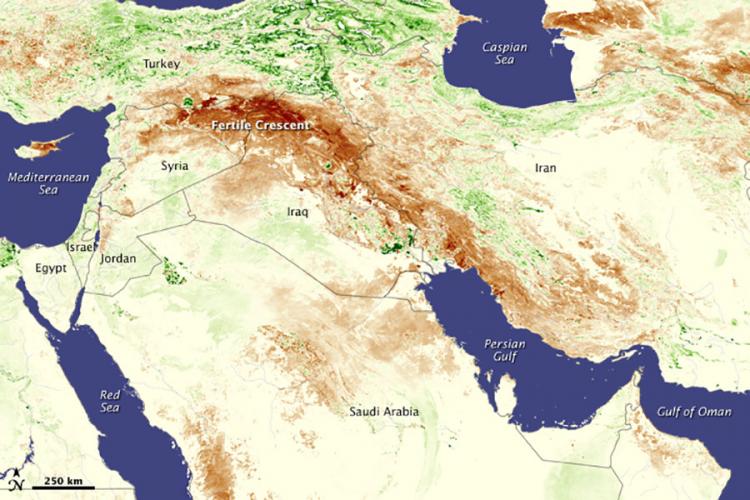

Taken in 2008, this satellite image reveals drought’s toll on agriculture in the Fertile Crescent. Colors reflect differences in plant growth between a drought year and the regional averages, with brown indicating less-than-average vegetation growth; green highlights regions with more vegetation, mostly reflecting irrigated farmland.

CREDIT: NASA

Bashar al-Assad, who succeeded his father in 2000, had cut fuel and food subsidies that Syrians had depended on under the prior regime. Despite the drought, he continued the cuts.

“Syria was actually highly vulnerable at the time that they encountered this drought, much more vulnerable than I think a lot of people realized,” Kelley says.

A world on notice

On June 1, President Donald Trump announced that the United States would abandon the 2015 Paris Agreement, a 195-nation pact to reduce greenhouse gas emissions worldwide and combat climate change. But military leaders and foreign policy experts have long recognized the risks that climate change poses to global security, naval ports and other defense infrastructure, military operations around the globe and stability at home. Among them is Defense Secretary James Mattis. For years the Defense Department has considered the impacts of climate change in planning documents such as its Quadrennial Defense Review.

A report earlier this year from the German think tank adelphi, Insurgency, Terrorism and Organized Crime in a Warming Climate, found that terrorist groups are increasingly using natural resources such as water as weapons of war. “This dynamic might be exacerbated as climate change increases the scarcity of natural resources in certain regions of the world: the scarcer resources become, the more power is given to those who control them,” wrote the report’s authors, Katharina Nett and Lukas Rüttinger.

Despite political changes in Washington, the Defense Department is expected to continue planning for the risks posed by continued climate change around the globe, says Femia of the Center for Climate Change and Security. “No matter what comes out of the White House, the Department of Defense is going to have to continue to adapt its infrastructure, to adapt its fighting force, to adapt its strategy to a changing geostrategic landscape in the face of a changing climate,” he says.

A cautionary tale

Those hoping to better prepare for climate changes over the next decades might gain a sense of urgency by looking at how past humans coped with great shifts in climate.

The collapse of the Classic Maya civilization in the ninth century offers a cautionary tale. The Maya inhabited present-day southeastern Mexico and the Yucatan peninsula for more than 2,000 years, building large cities with monumental architecture and developing a rich culture with a complex written language, a sophisticated calendar system and an expansive knowledge of astronomy. At the foundation of this thriving culture was an agricultural system based on maize.

Research examining the collapse of ancient civilizations has found that a number overlapped with deviations in climate.

CREDIT: S. HSIANG ET AL/SCIENCE 2O13

After about 350 CE, however, the Maya experienced three prolonged periods of warming that spiked summer temperatures, depressing crop yields and leading to repeated convulsions of conflict as ruling elites resorted to war to retain power. This was the conclusion of a May 2017 study in Quaternary Science Reviews by researchers at Simon Fraser University in Canada and the University of Aberdeen in the UK.

Increases in the number of violent conflicts between the years 350 and 900 were dramatic: There were zero to three such conflicts every 25 years in the first two centuries, but an average of 24 every 25 years toward the end of the period. For their study, the researchers analyzed 144 “unique conflict events” inscribed on Classic Maya monuments and described in dozens of scholarly works.

Researchers propose that warmer average temperatures at first led to greater crop yields and a subsequent rise in urban populations. But as temperatures continued to rise, the region experienced more days at or above 86 degrees Fahrenheit, crop shortfalls occurred more frequently and “the recently expanded population experienced longer, more frequent periods of food shortage, leading to increased levels of conflict.”

Climatic change may not have directly led to conflict for the Maya. But it seems to have paralleled a state of constant collective violence that ultimately exhausted one of history’s great civilizations. By the ninth century, after hundreds of years of repeated internecine warfare, the Classic Maya civilization had collapsed.

Climate’s civilizing influence

Climate shifts have always shaped the course of human history. Warm periods have given way to cold periods, times of drought to times of deluge. But human civilization, built on the domestication of agriculture and the rise of cities and nation-states, has coincided with a relatively stable period in Earth’s long history. The last ice age ended 11,700 years ago. The hothouse climate of the dinosaurs hasn’t come around in 65 million years.

By the end of the twenty-first century, however, the stable period people have enjoyed for millennia may come to an end. The concentration of heat-trapping carbon dioxide in the atmosphere reached a global average of 405.27 parts per million in July, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Earth hasn’t seen that concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide in about 4.5 million years, the geologic record shows. The consequences of this increase are apparent particularly in the Arctic, which is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet — resulting in the rapid melting of sea ice and land glaciers and a subsequent rise in sea levels around the globe.

As the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continues to rise, global temperature records are repeatedly being broken. The last 16 years make up 16 of the 17 hottest on record.

CREDIT: ANTTI LIPPONEN/FINNISH METEOROLOGICAL INSTITUTE

If the burning of fossil fuels continues unabated, by mid-century global CO2 could reach levels not seen in 50 million years, according to a study published in Nature Communications in April 2017 by Gavin Foster of the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom. Back then, during a previous geologic epoch known as the Eocene, mean global temperatures were about 86 degrees Fahrenheit, with little variation from pole to pole. It rained a lot, and the world was essentially ice-free. “If CO2 continues to rise further into the twenty-third century,” Foster and his colleagues wrote in their study, “then the associated large increase in radiative forcing, and how the Earth system would respond, would likely be without geological precedent in the last half a billion years.”