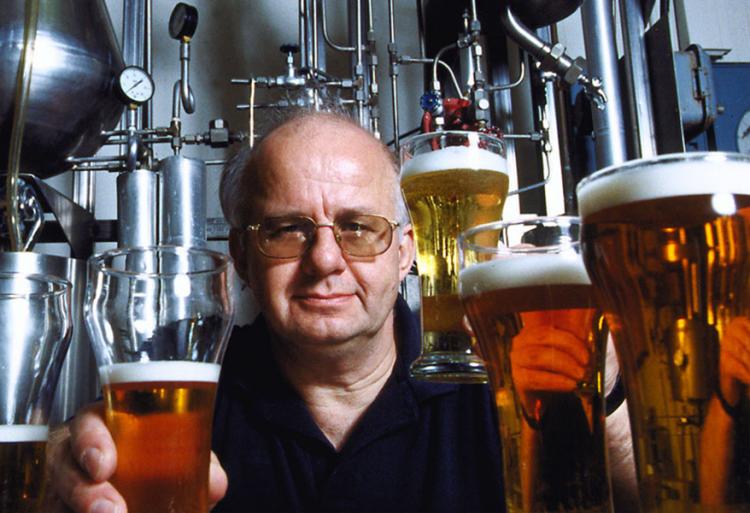

Brewing professor Charlie Bamforth in the former UC Davis campus brewery.

CREDIT: UC DAVIS

After 40 years of brewing research, Charlie Bamforth is retiring. His decades spent in the pursuit of quality beer “have been good to me, but now it’s time to relax,” he says. From his start as an enzymologist at the Brewing Research Foundation in England to his waning research days at the University of California, Davis, Bamforth has seen brewing research grow, shrink and adapt as technology and beer tastes propelled the field forward.

Hailed as the “Pope of Foam” by some beer enthusiasts, and author of such books as Beer Is Proof God Loves Us, Bamforth describes himself as a “hoary, crusty old Englishman” — an astute assessment, given his strongly voiced opinions on all things beer. He holds forth from his UC Davis office, a beer-friendly bastion tucked into a corner of a building filled largely with wine researchers.

On how enjoyment is in the mouth of the drinker: Bamforth laments how judgmental some beer drinkers — and brewers — have become. Some self-appointed arbiters of good taste deride mass-produced commercial brews as “fizzy, yellow liquid,” implying that these beverages aren’t proper beer.

But as long as it’s made with care, there’s no such thing as a universally bad beer, Bamforth argues. “There are millions of people in the United States who prefer to drink Bud and Coors and Miller,” he says, preferences that are perfectly acceptable.

He sees a growing lack of tolerance in the beer world — a feeling of superiority he feels should not exist. “There are different beers for different times, and different beers for different people.” And that’s OK.

Why the term “craft beer” is nonsense: “I hate the word craft,” Bamforth says. “All brewers are craftspersons. It doesn’t matter how big or how small you are.” With the right focus on technique, quality and consistency, anyone who brews can turn out a solid beer, he says. “There are some large brewing companies who, to me, epitomize everything about the concept of craft — great companies who believe in doing it right.”

One example, he says, is Sierra Nevada, a company founded by self-taught brewer Ken Grossman. (Along with other companies, Sierra Nevada has helped support research done in the UC Davis beer program.) “He wouldn’t put the beer into the market until he was happy that it was good and he could do it time and time again,” Bamforth says. “That’s the attitude you’ve got to have.”

On beer’s superiority over wine: “I’ve got to be quiet,” Bamforth murmurs, leaning in. “There are a lot of wine people around here.” But that doesn’t stop him from saying that wine’s reputation is unearned. “Wine has achieved this perception of being more sophisticated: ‘It’s better for food, it’s better for your health, it’s harder to do.’ The truth is the exact opposite of all that.”

Beer, with its near limitless improvisations, is more interesting, Bamforth argues. Beer is also a better accompaniment to food, he says, before going on to describe an incredible pairing between a sour beer and a rich, buttery cheese. And while wine inconsistencies can be celebrated as varietal quirks, beer gets no such leniency. “Wine guys get to throw up their hands and say, ‘Oh, it’s the vintage,’” he says. “Brewers don’t get to do that.”