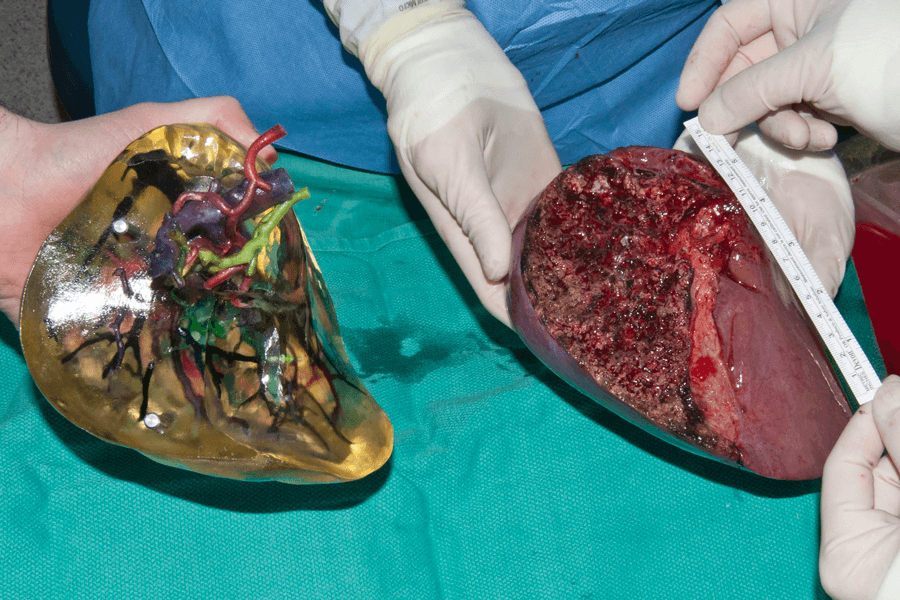

3-D-printed body organs like this liver lobe, shown next to the flesh-and-blood lobe, can help physicians plan and practice surgeries such as transplants.

CREDIT: N.N. ZEIN ET AL / LIVER TRANSPLANTATION 2013

What you see in the image above is a lobe of a liver, times two — on the right, a flesh-and-blood one, removed from a transplant donor, and on the left, one created from plastic to represent bile ducts, arteries and veins, laid down, layer by layer, by a 3-D printer. The goal of such technology: to help surgeons plan and practice complex procedures and train new surgeons with simulators that respond as a patient would.

Surgeons navigate complex anatomical terrain as they manipulate scalpel and suture to cut and stitch precisely and quickly. Their job is made harder by the fact that human anatomy is far from uniform. To properly prepare, they routinely use two-dimensional images from computerized tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to plan.

But increasingly they are turning to realistic 3-D models that are specific for individual patients.

Such models are already used to educate patients, to do general training and to plan and practice especially difficult procedures. But in the future, 3-D models, be they physical or virtual, could become routine tools for training surgeons or mapping procedures in advance.

From 2-D to 3-D

To 3-D-print, researchers first combine the many successive digital 2-D slices from CT or MRI scans into a topographic map that highlights the complex structures at different levels of the organ. The printers then build the models, layer by layer — sometimes using an inkjet to deposit droplets of resin that are fixed into place by shining UV light, or by extruding polymer ribbons that harden once they’re released.

The technology was first developed in the 1980s, when such printers were expensive and temperamental and materials were limited. But in the last few years, advances have made it affordable even for home users, and improvements in software and printing methods have enabled scientists and engineers to print complex mixtures of colors and textures with high accuracy, thus creating far more accurate and realistic organ models, as outlined in an overview in the 2018 Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry.

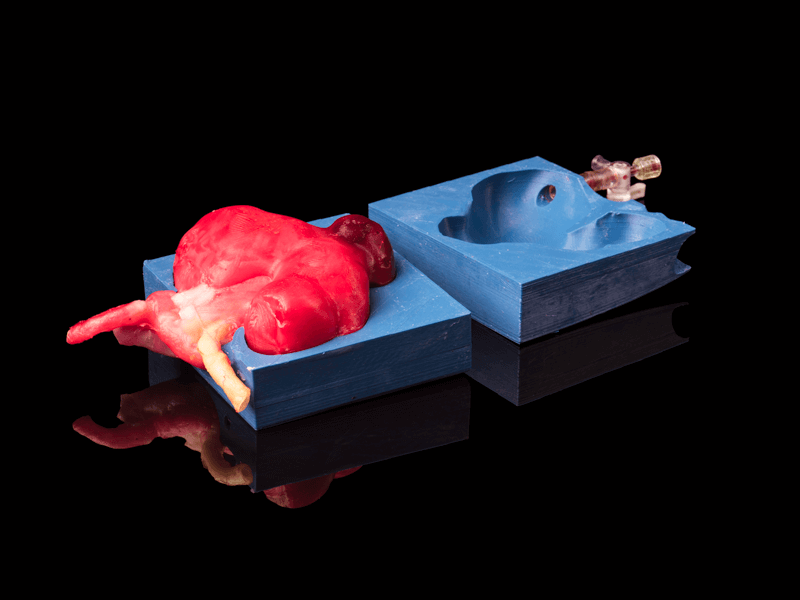

This artificial kidney with a tumor was created in a 3-D-printed mold. Jiggly hydrogels poured into the mold give the resulting organ realistic properties of muscle, fat or other tissues.

CREDIT: ADAM FENSTER, UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER

Cleveland Clinic gastroenterologist Nizar Zein first considered the idea of printing organ models in 2012 after reading about people constructing houses with 3-D printers and the technology’s potential uses in space exploration. He wondered if the method could make liver transplants from living donors safer.

Each liver has a unique, complex web of arteries, veins and bile ducts, and a misplaced cut can lead to complications, even death, in donor or recipient. So Zein assembled a team of clinicians, imaging experts, engineers and software designers to produce a patient-specific printed liver from resin to guide the surgical process.

The first prototype was crude — “really like a child playing with Play-Doh,” Zein recalls. Less than three-quarters life size, it wasn’t fully transparent and lacked color codes for different tissue types. But it was promising enough to show to surgical colleagues as they discussed a high-profile case where a liver donor suffered a dangerous complication on the operating table. One of those surgeons, Zein recalls, said that such a model might have saved the donor.

Zein refined the model, and in 2013 started studying how a life-size 3-D liver model, in addition to 2-D scans, would change how surgeons planned operations. An initial small study showed that their models matched the live organs in both anatomy and shape. Zein and his team’s models have been used in more than 20 surgeries. In many cases, looking at the model caused surgeons to change how they cut into the organ, Zein says, and in one case led the surgeons to conclude that the donor wasn’t suitable.

Zein’s team has gone on to print 3-D models of complex liver tumors to understand how they are connected to the organ, and thus inform surgical planning. “The more we know in advance about the patient’s anatomy and structures, the better off the surgery would be,” Zein says.

Soft models that bleed

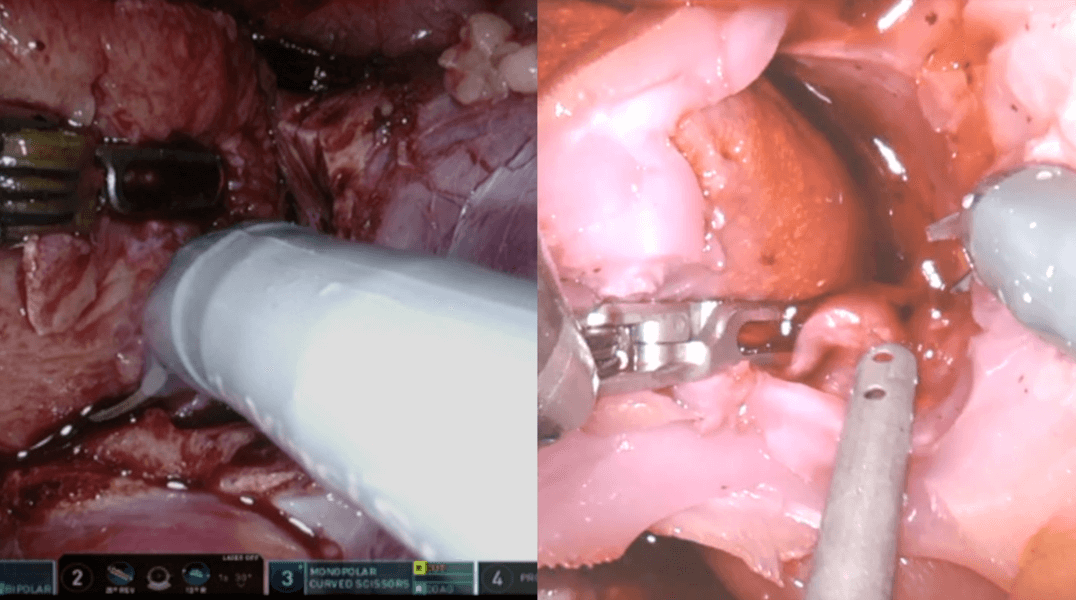

Organ models can also help train doctors. Urologist Ahmed Ghazi of the University of Rochester was inspired to build realistic kidney models that would provide an immersive way to simulate surgeries. “I just wanted something that looks like a kidney that bleeds,” he says. Kidney surgeons are often faced with removing tumors from an organ riddled with blood vessels, and may have just 30 minutes to complete their work before kidney tissue, clamped off from circulating blood, starts to die.

Some artificial organ models (right) are constructed so that they “bleed,” as the real organ would during surgery (left). This operation was to remove a kidney tumor.

CREDIT: AHMED GHAZI

To build a kidney model, Ghazi’s team layers simulated fat, intestines and other tissues in an abdomen-like cavity, just as they would be situated within a patient. “The surgeon is able to do the procedure from the beginning to the very end,” Ghazi says. He and his colleagues have made general models for teaching as well as ones from scans of individual patients for simulating specific surgeries. Ghazi has tested this system with five expert and ten novice surgeons on a common but challenging procedure for breaking up large kidney stones. Experts found the model very realistic, and the novices unanimously agreed that it would help to practice with these models before surgery.

Biomedical imaging expert Nicole Wake, now at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, also has looked at how kidney models affect surgery planning. In a 2017 study, she and her colleagues asked three experienced surgeons to review ten different complex kidney surgeries. They first reviewed 2-D images from the patients and described their surgical plan. A week or more later, they repeated the exercise with a 3-D model. In all cases, at least one of the surgeons then altered their strategy — changing how they would access or clamp the organ, for example — and reported greater confidence in their plan.

Materials make the model

In building 3-D organ models, the choice of material depends on its intended use, Zein says. Hard plastic is cheaper and adequate for simple 3-D visualization where clinicians want to zero in on visual features — a tumor’s shape, say, or the curving paths of blood vessels or ducts.

But spongier, more flexible materials including silicones, soft plastics and hydrogels are more realistic. Their springiness can mimic the mechanical properties of living tissue, providing a practice organ that surgeons may slice open, gauging width and depth of the necessary cuts to clear out tumors and guide repairs. Softer models can also incorporate other features, such as pressure sensors, that give surgeons more information as they prepare.

Ghazi and colleagues have created a range of tissue-textured models. Instead of printing them directly, the team uses the 3-D printer to create a series of detailed molds. They then inject specialized hydrogels — jiggly plastics that in their recipe consist of 70 percent water — that they tune to respond like muscle, fat or blood vessels. They even incorporate fluids so that slicing blood vessels or other ducts makes the organs bleed or seep as they would in an actual operation.

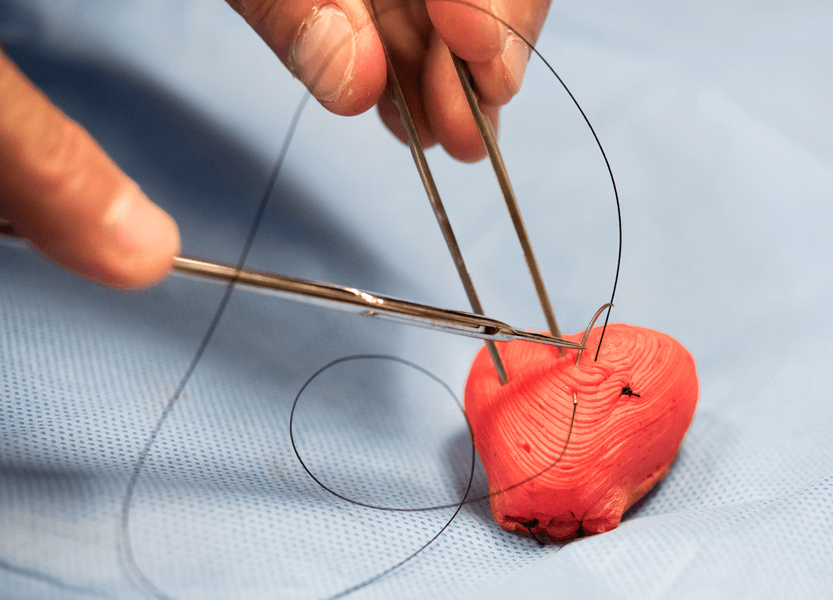

Mechanical engineer Michael McAlpine of the University of Minnesota has produced organ models of prostates that mimic the tissue’s mechanical properties, as training tools for surgeons. His team used samples of prostates removed from cancer patients to test properties such as firmness and flexibility. They replicated these features by adjusting the silicone ink’s chemical components to change how many links the polymers make between chains, rendering the models softer or stiffer.

They’ve even outfitted the prostate models with printed, pressure-sensitive sensors made from hydrogels and rubbery silicone. The sensors can measure the force applied by endoscopes or surgical scissors, providing doctors with useful information before they enter the operating room.

This 3-D-printed prostate can be equipped with pressure sensors that allow surgeons to practice on material with a lifelike feel as they rehearse procedures.

CREDIT: K. QIU ET AL / ADVANCED MATERIALS TECHNOLOGIES 2018

From physical to virtual

It’s unclear how many US hospitals are printing 3-D organ models. “I suspect most medium to large hospitals are at least trying it out,” says William Weadock, a University of Michigan radiologist and chair of the Radiological Society of North America’s 3-D printing special interest group. Medical centers with the equipment and expertise can now print some types of organ models for no more than a few hundred dollars for a hard plastic model. And companies such as Lazarus 3D and Materialise now offer to produce organ models from imaging data.

But regulatory agencies and health insurance companies are still catching up with this technology. Just one software package, produced by Materialise, is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for constructing the printing files for diagnosis in patients, and insurance doesn’t pay for such patient-specific models.

Printed organ models might turn out to be a stepping-stone toward immersive computer-based models that use augmented reality wherein surgeons use headsets and other tools to observe and manipulate 3-D representations. Originally, Ghazi had wanted to start his work this way, but he soon moved to physical models: It’s not yet possible to cut something virtually with the right “feel,” or to know how much an organ might bleed if cut in one spot or another. For now he is working with virtual reality companies — offering physical models as realistic tools for developing programming software for virtual surgeries.

In time, practice surgeries using 3-D imaging — be it augmented reality or printed, physical models — could become the norm rather than the exception, McAlpine says. “I think that will become extremely routine.”