Many people have declared 2020 the worst year ever. While such a description may seem hopelessly subjective, according to one measure, it’s true.

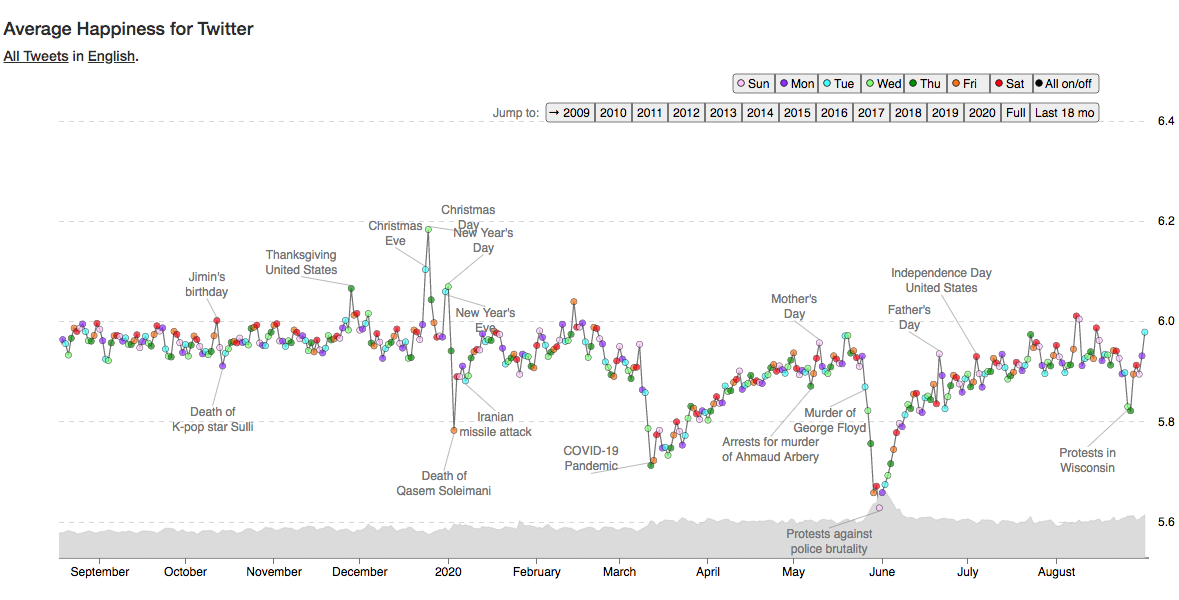

That yardstick is the Hedonometer, a computerized way of assessing both our happiness and our despair. It runs day in and day out on computers at the University of Vermont (UVM), where it scrapes some 50 million tweets per day off Twitter and then gives a quick-and-dirty read of the public’s mood. According to the Hedonometer, 2020 has been by far the most horrible year since it began keeping track in 2008.

The Hedonometer is a relatively recent incarnation of a task computer scientists have been working on for more than 50 years: using computers to assess words’ emotional tone. To build the Hedonometer, UVM computer scientist Chris Danforth had to teach a machine to understand the emotions behind those tweets — no human could possibly read them all. This process, called sentiment analysis, has made major advances in recent years and is finding more and more uses.

CREDIT: COMPUTATIONAL STORY LAB AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT

In addition to taking Twitter user’s emotional temperature, researchers are employing sentiment analysis to gauge people’s perceptions of climate change and to test conventional wisdom such as, in music, whether a minor chord is sadder than a major chord (and by how much). Businesses who covet information about customers’ feelings are harnessing sentiment analysis to assess reviews on platforms like Yelp. Some are using it to measure employees’ moods on the internal social networks at work. The technique might also have medical applications, such as identifying depressed people in need of help.

Sentiment analysis is allowing researchers to examine a deluge of data that was previously time-consuming and difficult to collect, let alone study, says Danforth. “In social science we tend to measure things that are easy, like gross domestic product. Happiness is an important thing that is hard to measure.”

Deconstructing the ‘word stew’

You might think the first step in sentiment analysis would be teaching the computer to understand what humans are saying. But that’s one thing that computer scientists cannot do; understanding language is one of the most notoriously difficult problems in artificial intelligence. Yet there are abundant clues to the emotions behind a written text, which computers can recognize even without understanding the meaning of the words.

The earliest approach to sentiment analysis is word-counting. The idea is simple enough: Count the number of positive words and subtract the number of negative words. An even better measure can be obtained by weighting words: “Excellent,” for example, conveys a stronger sentiment than “good.” These weights are typically assigned by human experts and are part of creating the word-to-emotion dictionaries, called lexicons, that sentiment analyses often use.

But word-counting has inherent problems. One is that it ignores word order, treating a sentence as a sort of word stew. And word-counting can miss context-specific cues. Consider this product review: “I’m so happy that my iPhone is nothing like my old ugly Droid.” The sentence has three negative words (“nothing,” “old,” “ugly”) and only one positive (“happy”). While a human recognizes immediately that “old” and “ugly” refer to a different phone, to the computer, it looks negative. And comparisons present additional difficulties: What does “nothing like” mean? Does it mean the speaker is not comparing the iPhone with the Android? The English language can be so confusing.

To address such issues, computer scientists have increasingly turned to more sophisticated approaches that take humans out of the loop entirely. They are using machine learning algorithms that teach a computer program to recognize patterns, such as meaningful relationships between words. For example, the computer can learn that pairs of words such as “bank” and “river” often occur together. These associations can give clues to meaning or to sentiment. If “bank” and “money” are in the same sentence, it is probably a different kind of bank.

A major step in such methods came in 2013, when Tomas Mikolov of Google Brain applied machine learning to construct a tool called word embeddings. These convert each word into a list of 50 to 300 numbers, called a vector. The numbers are like a fingerprint that describes a word, and particularly the other words it tends to hang out with.

To obtain these descriptors, Mikolov’s program looked at millions of words in newspaper articles and tried to predict the next word of text, given the previous words. Mikolov’s embeddings recognize synonyms: Words like “money” and “cash” have very similar vectors. More subtly, word embeddings capture elementary analogies — that king is to queen as boy is to girl, for example — even though it cannot define those words (a remarkable feat given that such analogies were part of how SAT exams assessed performance).

Mikolov’s word embeddings were generated by what’s called a neural network with one hidden layer. Neural networks, which are loosely modeled on the human brain, have enabled stunning advances in machine learning, including AlphaGo (which learned to play the game of Go better than the world champion). Mikolov’s network was a deliberately shallower network, so it could be a useful for a variety of tasks, such as translation and topic analysis.

Deeper neural networks, with more layers of “cortex,” can extract even more information about a word’s sentiment in the context of a particular sentence or document. A common reference task is for the computer to read a movie review on the Internet Movie Database and predict whether the reviewer gave it a thumbs up or thumbs down. The earliest lexicon methods achieved about 74 percent accuracy. The most sophisticated ones got up to 87 percent. The very first neural nets, in 2011, scored 89 percent. Today they perform with upwards of 94 percent accuracy — approaching that of a human. (Humor and sarcasm remain big stumbling blocks, because the written words may literally express the opposite of the intended sentiment.)

Despite the benefits of neural networks, lexicon-based methods are still popular; the Hedonometer, for instance, uses a lexicon, and Danforth has no intention to change it. While neural nets may be more accurate for some problems, they come at a cost. The training period alone is one of the most computationally intensive tasks you can ask a computer to do.

“Basically, you’re limited by how much electricity you have,” says the Wharton School’s Robert Stine, who covers the evolution of sentiment analysis in the 2019 Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application. “How much electricity did Google use to train AlphaGo? The joke I heard was, enough to boil the ocean,” Stine says.

In addition to the electricity needs, neural nets require expensive hardware and technical expertise, and there’s a lack of transparency because the computer is figuring out how to tackle the task, rather than following a programmer’s explicit instructions. “It’s easier to fix errors with a lexicon,” says Bing Liu of the University of Illinois at Chicago, one of the pioneers of sentiment analysis.

Measuring mental health

While sentiment analysis often falls under the purview of computer scientists, it has deep roots in psychology. In 1962, Harvard psychologist Philip Stone developed the General Inquirer, the first computerized general purpose text analysis program for use in psychology; in the 1990s, social psychologist James Pennebaker developed an early program for sentiment analysis (the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count) as a view into people’s psychological worlds. These earlier assessments revealed and confirmed patterns that experts had long-observed: Patients diagnosed with depression had distinct writing styles, such as using pronouns “I” and “me” more often. They used more words with negative affect, and sometimes more death-related words.

Researchers are now probing mental health’s expression in speech and writing by analyzing social media posts. Danforth and Harvard psychologist Andrew Reece, for example, analyzed the Twitter posts of people with formal diagnoses of depression or post-traumatic stress disorder that were written prior to the diagnosis (with consent of participants). Signs of depression began to appear as many as nine months earlier. And Facebook has an algorithm to detect users who seem to be at risk of suicide; human experts review the cases and, if warranted, send the users prompts or helpline numbers.

Yet social network data is still a long way from being used in patient care. Privacy issues are of obvious concern. Plus, there’s still work to be done to show how useful these analyses are: Many studies assessing mental health fail to define their terms properly or don’t provide enough information to replicate the results, says Stevie Chancellor an expert in human-centered computing at Northwestern University, and coauthor of a recent review of 75 such studies. But she still believes that sentiment analysis could be useful for clinics, for example, when triaging a new patient. And even without personal data, sentiment analysis can identify trends such as the general stress level of college students during a pandemic, or the types of social media interactions that trigger relapses among people with eating disorders.

Reading the moods

Sentiment analysis is also addressing more lighthearted questions, such as weather’s effects on mood. In 2016, Nick Obradovich, now at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, analyzed some 2 billion posts from Facebook and 1 billion posts from Twitter. An inch of rain lowered people’s expressed happiness by about 1 percent. Below-freezing temperatures lowered it by about twice that amount. In a follow-up — and more disheartening — study, Obradovich and colleagues looked to Twitter to understand feelings about climate change. They found that after about five years of increased heat, Twitter users’ sense of “normal” changed and they no longer tweeted about a heat wave. Nevertheless, users’ sense of well-being was still affected, the data show. “It’s like boiling a frog,” Obradovich says. “That was one of the more troubling empirical findings of any paper I’ve ever done.”

Monday’s reputation as the worst day of the week was also ripe for investigation. Although “Monday” is the weekday name that elicits the most negative reactions, Tuesday was actually the day when people were saddest, an early analysis of tweets by Danforth’s Hedonometer found. Friday and Saturday, of course, were the happiest days. But the weekly pattern changed after the 2016 US presidential election. While there’s probably still a weekly signal, “Superimposed on it are events that capture our attention and are talked about more than the basics of life,” says Danforth. Translation: On Twitter, politics never stops. “Any day of the week can be the saddest,” he says.

Another truism put to the test is that in music, major chords are perceived as happier than minor chords. Yong-Yeol Ahn, an expert in computational social science at Indiana University, tested this notion by analyzing the sentiment of the lyrics that accompany each chord of 123,000 songs. Major chords indeed were associated with happier words, 6.3 compared with 6.2 for minor chords (on a 1-9 scale). Though the difference looks small, it is about half the difference in sentiment between Christmas and a normal weekday on the Hedonometer. Ahn also compared genres and found that 1960s rock was the happiest; heavy metal was the most negative.

Business acumen

The business world is also taking up the tool. Sentiment analysis is becoming widely used by companies, but many don’t talk about it so precisely gauging its popularity is hard. “Everyone is doing it: Microsoft, Google, Amazon, everyone. Some of them have multiple research groups,” Liu says. One readily accessible measure of interest is the sheer number of commercial and academic sentiment analysis software programs that are publicly available: A 2018 benchmark comparison detailed 28 such programs.

Some companies use sentiment analysis to understand what their customers are saying on social media. As a possibly apocryphal example, Expedia Canada ran a marketing campaign in 2013 that went viral in the wrong way, because people hated the screechy background violin music. Expedia quickly replaced the annoying commercial with new videos that made fun of the old one — for example, they invited a disgruntled Twitter user to smash the violin. It is frequently claimed that Expedia was alerted to the social media backlash by sentiment analysis. While this is hard to confirm, it is certainly the sort of thing that sentiment analysis could do.

Other companies use sentiment analysis to keep track of employee satisfaction, say, by monitoring intra-company social networks. IBM, for example, developed a program called Social Pulse that monitored the company’s intranet to see what employees were complaining about. For privacy reasons, the software only looked at posts that were shared with the entire company. Even so, this trend bothers Danforth, who says, “My concern would be the privacy of the employees not being commensurate with the bottom line of the company. It’s an ethically sketchy thing to be doing.”

It’s likely that ethics will continue to be an issue as sentiment analysis becomes more common. And companies, mental health professionals and any other field considering its use should keep in mind that while sentiment analysis is endlessly promising, delivering on that promise can still be fraught. The mathematics that underly the analyses is the easy part. The hard part is understanding humans. As Liu says, “We don’t even understand what is understanding.”