Grandma’s picture books had colored ink. Dad’s had pop-outs and fun textures.

Today kids’ books can feature videos in place of illustrations, define words aloud and have characters that walk across the page.

As traditional books evolve and mingle with portable device technology, parents, educators and developmental psychologists want to know what the consequences may be. Are so many bells and whistles in children’s early reading material helpful, benign or maybe even harmful?

Proponents of digital storybooks say that the interactive features increase child and parent engagement, accelerating children’s grasp on reading and language. Critics say the format is distracting and impedes focus and comprehension of the content. “On both sides, there are studies saying that e-books are detrimental and studies saying that there’s no difference,” says education and learning researcher Brenna Hassinger-Das of Pace University in New York City, who coauthored an overview of young children and digital media in the 2020 Annual Review of Developmental Psychology. “E-books are constantly changing, too, which is the other piece … and we’re trying to keep up with all the developments.”

The answers are important, Hassinger-Das adds, because e-books are becoming ever more interactive and popular. Since the 2010s, when use of products like smartphones and the iPad were becoming widespread, e-book–compatible devices have become more common in the home; libraries continue to expand their e-book collections; and schools increasingly include them in their curricula. As reading time and screen time become one and the same, parents of young children find it harder to draw the line between time well spent and time wasted.

Though the science is far from settled, themes are emerging: that less is more when it comes to fancy features, and that parent involvement is key — in most cases, anyway. As artificial intelligence and interactive reading apps continue to develop, some educators and researchers see equalizing potential for situations where parents, for whatever reason, don’t or can’t read to their young children.

Adventures in childhood literacy

Children’s literacy tools were in use long before societies considered reading a necessary part of every child’s development. “Children’s books have always wanted to help make the best possible child, the happiest child, the child who knows things, who understands the world, understands themselves,” says Kim Reynolds, a historian of children’s literature at Newcastle University in the UK.

The children of nobles in ancient Rome read stories handwritten on scrolls, but it wasn’t until the 1400s, after invention of the printing press, that children’s reading material (and literacy) became more widespread. Hornbooks — typically wooden paddles with a single sheet of vellum or paper overlaid with protective, transparent horn — became popular, though they were hardly books in the modern sense. They contained only what adults considered essential: the alphabet, numbers and the Lord’s Prayer. “The idea of what the best possible child is has changed a lot,” Reynolds says.

Hornbooks, named for the thin layer of transparent horn used to protect their inscriptions, were a popular early education tool in Europe and elsewhere for hundreds of years, beginning around the 1400s. These paddles typically included numbers, letters and the Lord’s Prayer or other Bible verses.

CREDIT: A.W. TUER, HISTORY OF THE HORN-BOOK / PUBLIC DOMAIN (LEFT); CHRIS DEVERS / FLICKR (RIGHT)

In 1744, John Newbery published A Little Pretty Pocket Book, widely considered to be the first kids’ book created purely for enjoyment, with games, funny stories and illustrations. By the 19th century, authors began to recognize that children, like adults, have their own internal conflicts, proclivities and fantasies. Fairy tales and fantastical stories such as The King of the Golden River and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland grew in popularity.

With the advent of radio, film, television and video games, children’s literature interacted with each new medium, providing fodder for story lines on the one hand and, say, adopting popular TV characters on the other. By the early 1990s, printed books began to offer buttons to trigger sounds. And in 1999, kids’ books took a big jump toward digital when the toy company LeapFrog released the LeapPad, a plastic, electronic holder for spiral-bound books that responded with sound effects, word definitions and stories when a child pressed “pen” to page.

E-book technology and options have massively expanded since Amazon’s 2007 release of the Kindle, followed by the development of the tablet and smartphone; their use in homes, schools and libraries is flourishing. To be sure, traditional books still predominate, but e-book use is on the rise and especially so among some demographic groups. A nationally representative survey on children ages zero to 8 conducted by the nonprofit organization Common Sense Media found that Black and lower-income families are using e-books as a greater percentage of their reading time than white or wealthy families are.

This could be important. Developmental psychologists, educators and literacy advocates have long known that reading to young children can improve their later reading proficiency and promote cognitive skills such as close listening, creative thinking and focusing for extended lengths of time. And the benefits accrue early, according to a study of 250 pairs of 6-month-old infants and their mothers presented at a 2017 Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. Both the amount of shared book-reading (numbers of books in the home and days spent reading) and its quality (the amount and nature of parent-child interaction) predicted better vocabulary, language and reading skills four years later.

Another study estimated that a child who is read to daily will hear an average of 1.4 million more words before the age of 5 than a child who is not, based on an analysis of 60 commonly read children’s books in the US.

Co-reading with traditional books involves interpreting illustrations together, turning pages or perhaps using a finger to follow along with the text. For e-books, the possible interactive features are far greater. Give the tablet a shake and the animated characters bobble their heads. Tap the screen and hear the cow say “Moo.” Help a character find her toy by dragging the illustrations around. How might these attractions (or distractions) affect the nature and benefits of co-reading?

To try and tease this apart, researchers at Temple University in Philadelphia and colleagues videotaped 92 pairs of parents and children age 3 or 5 co-reading traditional books or e-books for five minutes, then coded the spoken words and behaviors. The 2013 study found that when parent-child pairs read stories on a touch-sensitive, spiral-bound e-book console, they often took more than the allotted time to finish the books. That’s because “children wanted to activate every possible sound effect on each page before moving to the next page,” the authors wrote. Discussion centered more on behavior (“Stop pressing the button”) and less on connecting the story to the child’s life (“Remember when we went to the doctor, like Caillou?”).

In a follow-up study, 3-year-olds under both conditions were equally adept at easy things like identifying characters and events. But the traditional book group scored 15 percentage points higher, on average, for questions that asked them to recall more complex aspects of a story, such as sequence of events. This suggests that interactive features can distract early readers and reduce their overall learning and comprehension.

The PowerTouch learning console, pictured here, reads and spells words aloud and flashes lights when the child touches a finger to the page.

CREDIT: J. PARISH-MORRIS ET AL / MIND, BRAIN, AND EDUCATION 2013

A 2016 study by Hassinger-Das and colleagues found differently, though. In this case, 86 parent-child pairs (again 3- or 5-year-olds) were randomly assigned to read or listen to one of four types of books: a plain, noninteractive e-book, a “read to me” e-book with audio, an e-book with hot spots — such as a button that plays a video related to the story — or a traditional book. The participants were instructed to read “as you normally would” and their words and behaviors were coded. Then the researchers asked the children a series of story comprehension questions.

The researchers found no comprehension differences based on book type. But they did find a difference based on how the parents read with kids. Kids did better, no matter what kind of book they were being read, if the parents used a style known as dialogic reading, in which the adult poses questions and prompts the child to relate the story to their own life.

“Pointing out something on the page, like if there’s a bear or other animal, and saying, ‘Oh, remember when we went to the zoo and we saw a bear there and you liked it and you learned about it?’ Tying it in like that helps make it more meaningful for kids,” says Hassinger-Das. “They’re going to remember information when they connect it to their real life.”

Beyond that, she says, “If you have a paper book and an e-book and you are reading them in the same way, there’s not going to be any difference, in my mind.”

Assessing interactivity

Studies do suggest that interactive e-books could aid learning in situations where a parent isn’t available. In a 2020 study on 36 1-year-olds in Tokyo, the babies could learn the association between an on-screen object and a made-up word — as measured by their gaze — when, during the teaching phase, an animated character gestured towards the objects and responded to the infants’ gaze with “eye contact” and a smile. In trials where the character did not respond in humanlike ways, the infants did not learn these new word-object associations.

If e-books can provide meaningful, albeit artificial, social interaction that helps children absorb and retain information, “there are kids that I think would really benefit from that,” Hassinger-Das says. “Kids who are learning a second language, for example, and don’t have a parent who can read with them in that language.”

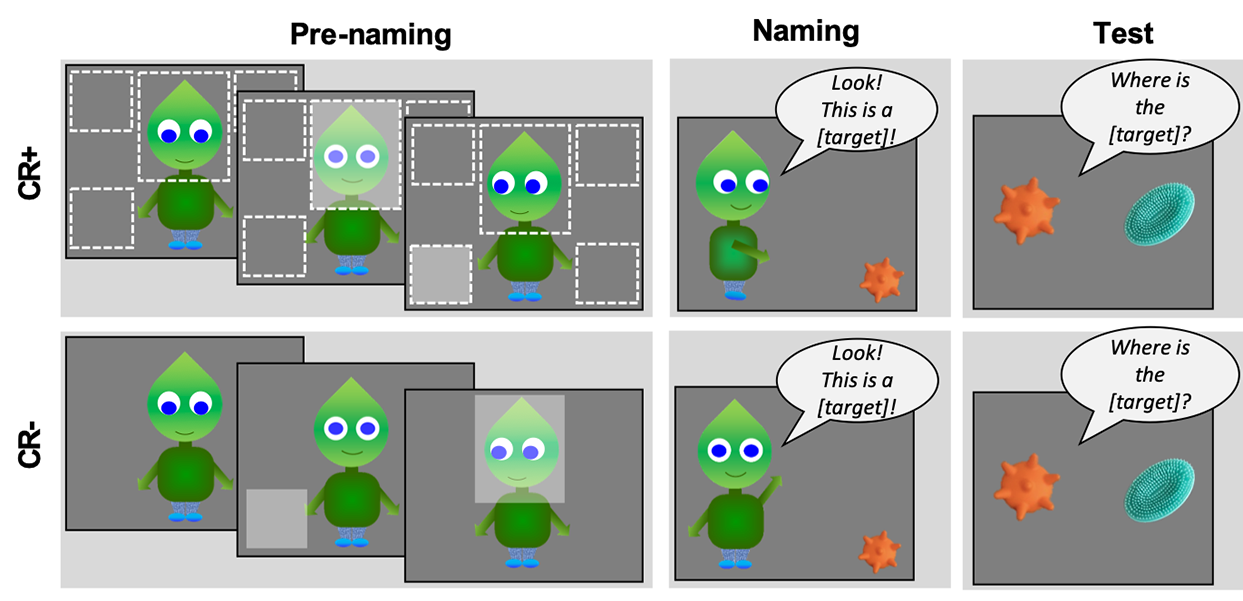

In an experiment, researchers placed one-year-old infants in front of a screen and tracked their gaze through three phases: “prenaming,” “naming” and “test.” In one group (labeled CR+, top), the green character smiled and made eye contact when the child looked at the character’s face. (The shaded boxes are spots where the infants looked during a particular trial.) In the other group (CR-, bottom), the timing of the character’s eyes and smile were preprogrammed and did not respond to the infants’ gaze.

For both groups, the prenaming phase allowed the child to become familiar with the character. The naming phase introduced a novel object paired with a simple, made-up word. During this phase, for the CR+ group the character turned, looked and pointed at the object, which gently inflated and deflated if the child looked at it too. For the CR- group, the character and object movements were preprogrammed.

During the test phase, two objects were presented, and the character asked the infant where the previously named object was. Infants in the CR+ group looked at the correct object a greater proportion of the time than infants in the CR- group — indicating that the interactive features helped the child to learn.

CREDIT: S. TSUJI ET AL / JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL CHILD PSYCHOLOGY 2020

E-books also might be particularly helpful for kids with learning challenges such as dyslexia, or for those who don’t have access to schools or other educational materials, says Maryanne Wolf, a cognitive neuroscientist at UCLA and cofounder of the nonprofit Curious Learning, which endeavors to bring e-books and reading apps to children around the world in such situations. “There are good uses for e-books — it’s not an either-or binary situation,” she says.

In 2012, for example, Curious Learning researchers conducted a pilot study in which they gave tablets preloaded with early literacy apps and e-books to 40 Ethiopian children ages 4 to 11 who had no school access and whose parents could not read. With no instructions given for using the devices, nine months later the children had taught themselves basic reading skills. Some could perform as well as American kindergartners on English vocabulary, letter sounds and reading tests. According to Curious Learning, four years later a handful of children who had continued to use the tablets were reading at a US first- or second-grade level in Oromo, their native language

A similar pilot study was conducted by Google before it released a free app called Read Along, which uses AI and speech recognition technology to help kids expand their reading skills. The ad-free program comes with some 500 stories and a “reading buddy” named Diya who recognizes and responds with visual and auditory cues when a child is struggling to read aloud or pronounce words.

Diya also gives positive feedback, “just as a parent or teacher would,” the Google developers say. In a 2019 summary describing reading proficiency after three months in some 1,500 children from rural villages in India, Google reported that 64 percent of the children who used Read Along improved their reading level, compared with just 40 percent of children who didn’t receive the app.

Such tech could, if used well, serve as an opportunity equalizer, Wolf says — by offering a lot of the benefits of co-reading to underserved children. But she is hesitant to turn to e-books as a reading tool for all early readers. Young children, she says, are too distractible. They can’t yet override the novelty, or orienting, reflex, an evolutionary response that causes us to automatically pay attention to new stimuli.

“All the bells and whistles that the digital materials bring to the child are actually overwhelming the attentional system,” Wolf says. “The child’s attention is going to be consistently, continuously distracted by all those extra things that the makers thought were very creative and exciting.”

Wolf advocates instead for a parallel use of print and digital media. Children could learn to read primarily from print materials for their first five to 10 years but be engaged with digital media for the development of other skills, such as learning how to use keyboards or the internet. “I believe, without a doubt, that this concept of a world steeped in both mediums is where we should go, but we should go there carefully,” she says.

Other researchers have deeper concerns about the physiological impacts of learning from screens. “There’s this myth that we’re going to invent a technology that’s better than the human experience,” says neuroscientist and pediatrician John Hutton of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, who studies early brain development. “We’re basically taking all this new technology and giving it to kids at younger and younger ages and expecting nothing bad to happen.”

“We, as a society, make children wait to do all kinds of things.... I would argue that very young children probably aren’t quite ready developmentally to use this technology yet.”

John HuttonIn 2019, Hutton and colleagues published a study in which they used magnetic resonance imaging to measure neural connectivity in the brains of 47 preschool-aged children from mostly middle- and upper-class families. The team looked at white matter, the bundles of nerve fibers that connect various regions of the brain and allow them to work in concert. In growing brains, Hutton says, the neural connections that are exercised often are physically reinforced, while those that are seldom used will weaken or eventually disappear. Speaking broadly, Hutton says, stronger connections mean more efficient signaling, which can result in quicker thinking and better memory.

Hutton’s study examined neural connections between several brain regions including Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, which are associated with language, speech and early literacy skills, and other regions related to executive function, such as staying on task and storing information. It compared scans of kids whose digital media use (as reported by parents) either exceeded, or didn’t exceed, limits advised by the American Academy of Pediatrics, including capping noneducational screen time at one hour per day.

As a group, kids exceeding those limits had weaker connections between some of these regions than kids whose screen time was lower, the study found. They also had lower reading and language skills, though household income level appeared to be a factor in those scores.

“When we published this study, the first thing a lot of news channels asked was, ‘Are you saying screen time causes brain damage, is it toxic?’” Hutton says. “And there’s really not a lot of evidence that it is.” The problem, he says, is more about activities that screen time is displacing — such as social interaction with family. Hutton says he is particularly concerned about the possible effects of screen time on early language development, because mastering language requires so much back and forth between adults and children.

Hutton thinks that e-books might have great potential as learning tools but sees reason to proceed with caution for young learners. The developing brain, he says, has sensitive periods for learning certain skills, and if a child doesn’t properly acquire a skill such as language during its associated critical period, they may never gain full proficiency. If excessive early e-book use means that children miss out on the benefits of co-reading with parents, there could be consequences, he says.

“We, as a society, make children wait to do all kinds of things,” he adds. “We make them wait to drive a car, to own a gun or cook on a stove. We do this because we don’t think they’re quite ready, and I would argue that very young children probably aren’t quite ready developmentally to use this technology yet.”

Early in a child’s life, there are some critical periods for brain development and for learning certain skills. Outside of these sensitive periods, learning the skills becomes less efficient, and full proficiency may never be achieved. For language-learning skills, the sensitive period peaks well before children start preschool.

Proceeding with caution

Many parents seem to be exercising caution. According to a 2014 survey of more than 1,500 American families, half of the parents of 2- to 10-year-olds who owned e-readers said their kids weren’t allowed to use them. About 45 percent said they preferred their child got the traditional book experience. Around 30 percent said they didn’t want e-books to add to the kids’ daily screen time, and 27 percent that they believed print books are better for children’s reading skills.

A similar survey, of 1,500 parents in the UK, found in 2016 that 35 percent of parents resisted interactive e-books out of concern that their children will lose interest in reading in print. Nearly two in three said they wanted more advice on using e-books in a way that will help their children learn, and nearly one in three said they felt confused about making the right choices about their children’s e-book use.

Parents who do use e-books surely want to make good choices. One tip, researchers say, is to turn to reviews and recommendations by Common Sense Media, which gauges the content of e-books and other media for educational worth as well as for teachable skills like integrity, self-direction and emotional development.

Another is to consider four principles or pillars of learning that developmental psychologists and early education specialists use to assess the quality of e-books and other media for children: that the content fosters active involvement, engages the child and is meaningful and socially interactive.

$[$PB_DROPZONE,id:knowable-newsletter-article-promo$]$

Jennifer Zosh, a human development researcher at Penn State Brandywine, says that the engagement pillar is especially difficult to perfect in children’s media because it’s easy for developers to get carried away with sound effects, little games and cool graphics. “Kids like it, it’s fun,” she says. “I think a lot of app developers do it to make the app entertaining, but it actually disrupts learning.”

Quality is a crucial consideration, say childhood learning advocates and researchers. They worry that poorer children are more likely to consume free content that often contains distracting ads or is designed to be entertaining rather than educational. “It’s hard work to figure out how educational something really is,” says Zosh, who coauthored a 2015 literature review on educational apps. “It’s so sad when you see kids playing with an alphabet learning app and then all of a sudden, here comes an advertisement for Candy Crush.”

And though many an e-book may boast that it’s “educational,” there are no universal standards around that term. “There are some really beautifully designed, well-researched e-book products and platforms, and there are also some really shoddy pieces put together with an eye toward making a buck off of a parent,” says child literacy advocate and author Lisa Guernsey, who directs the Teaching, Learning and Tech program at the think tank New America.

Well-designed e-books, Guernsey says, prioritize age-appropriate learning. Others — often the ones that attract the most customers — do too much. “There are some e-books that are trying to be very simple,” she says. “The sad thing is, I don’t think they’ve done very well in the marketplace.”

As books continue to develop and transmogrify into forms that our younger selves might barely recognize, disquieted parents can draw some comfort from considering the past, says Reynolds, the historian. “There was hostility to reading when reading first came in,” she reminds us. “And now we value reading and have hostility to other things that we think might be pulling children away from the values of the culture as we know it.

“I don’t think you need to be frightened of new media. Just wait and see how things cross-fertilize — and new things, new stories and new possibilities will come from them.”