The costs keep piling up: California’s 2018 fire season caused close to $150 billion in damages, and this year’s record-setting wildfires could prove just as dear. Rebuilding after Germany’s summer floods will probably cost more than 6 billion euros ($7.12 billion), the country’s finance minister says. And estimates place the damage from Hurricane Ida, which ripped from New Orleans to New York in August, at roughly $95 billion.

Fires, droughts, floods, storms, extreme heat: The uptick in natural disasters — a trend linked to global climate change with growing certainty — poses serious financial risks.

But the economic threats from climate change don’t end with cleanups and rising insurance premiums. As the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change observed in its latest report, such calamities will only accelerate unless nations achieve “deep reductions” in greenhouse gases in coming decades. The changes needed to slow warming are big enough that economies would have to adapt to make them happen. It may well mean upending many aspects of everyday life. Ultimately, many agree, it will require ditching fossil fuels for clean energy.

One of many forest fires burning in California in 2018, the Holy Fire sends embers above Lake Elsinore. The last five years have brought record-breaking fire seasons to the state and hundreds of billions in estimated damages. Climate change contributes to a rise in devastating natural disasters — including fires — which can carry huge price tags. But other financial risks accompany the shifts needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

CREDIT: KEVIN KEY / FLICKR

How nations could achieve this daunting shift, and how fast, is uncertain. For economists, uncertainty equals risk, and too much risk could jeopardize the stability of the financial system itself. Financial experts increasingly are discussing how to deal with one type of risk, called “transition risk,” that comes with a shift to a greener world.

Moving away from fossil fuels

Thus far, policymakers have been slow to enforce emissions limits, carbon taxes and other rules that would help reduce greenhouse gas emissions enough to achieve the oft-cited goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius. Carbon-dependent businesses, with no one pushing them to act, seem more than happy to kick the can down the road.

Companies in the S&P 500, for example — an index of large publicly traded firms that many investors track to get an idea of overall market health — need to reduce their carbon emissions from something like 14 gigatons of carbon dioxide per year down to zero, says Patrick Bolton, an economist at Columbia University. “How are you going to do that? At what pace? And at what cost?” he asks.

President Joe Biden speaks about climate change at an April 2021 virtual event for world leaders. That same month he set more ambitious targets for reducing emissions of greenhouse gases. Biden initiated efforts to study the US government’s climate-related financial risks and re-engaged in the Paris Climate Accords.

CREDIT: WHITE HOUSE PHOTO BY ADAM SCHULTZ

If climate goals are to be met, says Frederick van der Ploeg, an economist at the University of Oxford, it’s inevitable that large reserves of fossil fuels will have to remain in the ground unburned. As much as one-third of global oil reserves, half of gas reserves and 80 percent of coal reserves will have to be left unused to prevent temperature increases beyond 2 degrees, he and coauthor Armon Rezai of the Vienna University of Economics and Business noted in a 2020 review in the Annual Review of Resource Economics, citing 2015 work by Christophe McGlade and Paul Ekins. (An updated analysis, published in Nature in September, bolsters the earlier findings.)

This represents an enormous problem for oil and gas companies and their investors — and by extension, for all kinds of businesses that rely on fossil fuels to operate. At some point, all would have to make the leap from a carbon-intensive present to a green future. But that future hasn’t quite been worked out.

Maybe the companies will be able to get out ahead of the shift, and successfully redirect their holdings and operations on their own schedules. But if uncertainty persists, they’ll be left holding the bag when governments eventually do tighten emissions rules, or when a technology breakthrough makes green energy very cheap (van der Ploeg likens it to a game of musical chairs). Their formerly profitable reserves will become “stranded assets” — essentially, worthless. And that could have ripple effects across the global economy.

A large portion of “transition risk” comes from making the shift to renewable sources of energy, such as wind and solar, and away from fossil fuels — a move that will impact oil and gas holdings as well as other carbon-intensive industries and investments. One analysis that looked at a sampling of large banks’ holdings identified $500 billion of potential exposure to this kind of climate risk.

CREDIT: ALSEENRODELAP.NL – ELCO / SHUTTERSTOCK

Steven Rothstein, managing director of the Ceres Accelerator for Sustainable Capital Markets, an advocacy organization in Boston, cites an example. In 2020, he says, oil companies “wrote off” $145 billion from their ledgers, essentially abandoning investments in pipes and pumps and delivery equipment that they didn’t expect to need any longer as demand for oil and gas drilling and production falls off. “They’re saying, ‘I’m never going to get this money back because the price of the alternatives — solar and wind — has come down, and because of reputational risk,’” Rothstein says.

Their investors, including pension funds and other institutional investors who manage money for everyday folks, take the hit along with them. This was what happened to banks and firms that poured money into bundled subprime mortgages in the 2000s. They got into trouble when the housing bubble burst and it became clear the loans were never going to be paid back (and were therefore, like unusable oil, worthless). In a 2020 analysis of large banks’ exposure to climate transition risk, Rothstein and colleagues identified $500 billion of potential climate risk — and that was when they focused on just a portion of holdings, among a portion of banks. The real number is likely to be far larger.

“If you’re a bank regulator, and your job is to think about the safety and soundness of the banks, you have to care about this,” Rothstein says. “Unfortunately, financial actors haven’t been properly planning for climate risk.”

Getting to net zero carbon

The United States lags the field. The European Union, Japan, South Korea and other countries have promised to reach net zero carbon emissions — balancing emissions of greenhouse gases with active removal — by 2050; China has pledged to do so by 2060. But until very recently the US had not followed suit. Politicization of climate policy has slowed proactive efforts; Rothstein says that as recently as a year ago, he still came across government officials who questioned whether climate change was real.

In 2017, then-President Donald Trump withdrew the country from the landmark Paris Agreement; President Biden reversed this on his first day in office, enabling the US to rejoin earlier this year. In April, Biden also set new greenhouse gas reduction targets, pledging to reduce emissions by 50 percent to 52 percent from 2005 levels by 2030.

Biden’s executive order on climate and financial risk directs federal agencies to report in coming months how climate will change their work and what they plan to do about it. Federal employees may have options to invest their pension funds in green businesses. Vendors who sell goods and services to the federal government could be required to disclose emissions; the Securities and Exchange Commission may require companies listed on the stock exchanges to do the same.

More visibility into emissions data would allow financial markets to take climate risks into account in terms of pricing and investment. That, experts say, might reduce the chance of a financial crisis akin to the one that crashed the economy in 2008.

CREDIT: RICHARD LEVINE / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Reporting carbon emissions is crucial, says Bolton, to push policy in the right direction — and to stabilize economies as new environmental policies are put in place. “The broad reason why you want disclosure — and disclosure that gets audited — is that you get more accurate, granular information about where emissions are, who has to make the most adjustments, and who is at the most risk in the transition,” he says.

With greater access to emissions and other climate data, the thinking goes, companies and investors can make more rational decisions for the future — accurately pricing their assets, goods and services with climate financial risks in mind, making the transition process more “orderly” and avoiding shocks in situations like Rothstein’s oil company write-off example.

“You don’t want to invest in crops that are not heat-resistant, or in buildings that are not flood-resistant. You may be building in the wrong parts of the world. You might be too close to the coast, rather than five yards up the hill,” says van der Ploeg. “Now is the time to make the decision about the changes that we know will be inevitable. It’s not whether, it’s when.”

Making the transition transparent

The sooner the process gets going, experts say, the better. “The longer companies wait to close down their carbon-intensive assets, the more risk will be put in the system, and the more individual investors will be exposed,” says Irene Monasterolo, a climate economist at the Vienna University of Economics and Business and author of a 2020 review of climate change and finance research in the Annual Review of Resource Economics.

Better disclosures and procedures around climate risk may also fuel innovation and mitigation, says economist Andrew Lo, of the Sloan School of Management at MIT. “Financial markets play a central role, not just in dealing with climate change, but in dealing with all big challenges. No matter what the challenge is, no matter how we deal with it, there’s a common denominator. You need money. And when you need money, you need finance.”

Efficient financial markets, fueled by good information, could steer resources to technologies and companies that can speed the low-carbon transition. Markets can also function as a “sort of crystal ball,” Lo sys. “If there is a problem that is looming, you’ll see it first in the stock market. It is the canary in the coal mine.” Investors may demand a premium — a lower stock price — to purchase shares in firms with big exposure to climate risk.

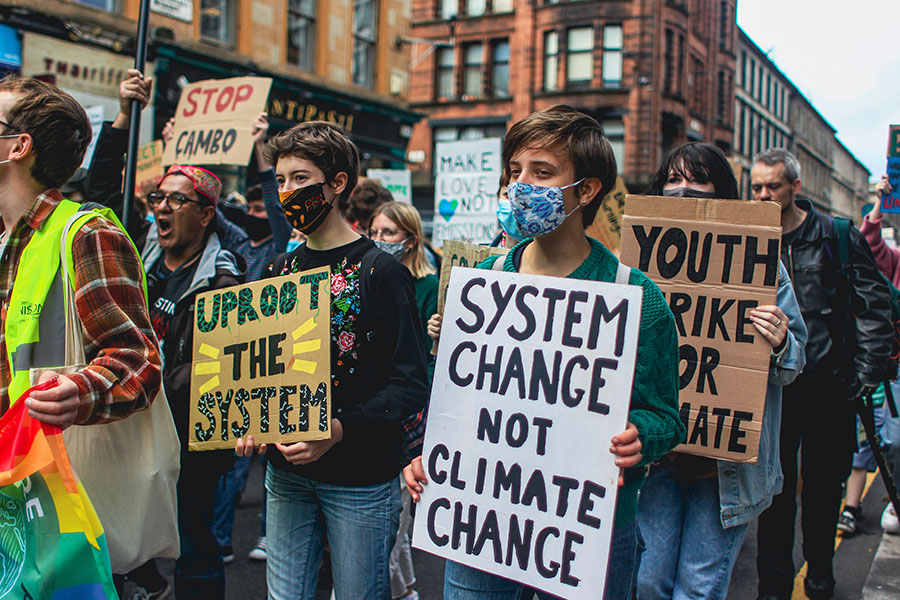

In advance of the United Nations global climate meeting to be held in Glasgow this fall, young protesters marched through the city calling for rapid action on emission reduction goals as part of an international youth movement. The U.N. summit will have many challenges to address, not least how to prepare for the financial implications of climate change.

CREDIT: PHOTO BY EWAN BOOTMAN / NURPHOTO VIA AP

Monasterolo works to develop “climate stress test” models that incorporate climate change and policies into financial risk assessments that can point the way ahead for financial authorities and investors managing climate-related financial risk. “Many existing climate economic models do not account for the role of finance and its complexity in mitigation trajectories,” she says. “Neglecting investors’ expectations toward climate policies and risks can give a false sense of security about the possibility of making the transition, and what is needed in terms of policies to achieve the Paris Agreement.”

When investors start to assess climate risks in their portfolios, she adds, companies feel the pressure to make changes. (In May, Monasterolo and coauthors published a study in Science that attempted to tease out “the interdependence between investors’ perception of future climate risk … and the allocation of investments in the economy.”)

Recent research by Bolton suggests that investors are already taking carbon emissions into account when they price stocks, finding that companies with more emissions garnered lower prices and thus higher returns. That’s a sign that the market may already be exerting influence on companies and climate outcomes.

But much work remains to be done. Bolton says that Biden’s executive order on climate-related financial risk is not enough to bring about all the needed changes. Congress may have to act to bring about a more ambitious climate policy that severely limits or taxes carbon emissions.

“Executive orders are a step in the right direction, but there’s only so much you can do with an executive order,” he says. “It can help set the agenda for regulatory agencies. You can prod them, but you can’t force them.”

The rest of the world hasn’t really figured out disclosures either, Bolton adds; he notes that financial disclosures are expected to be a major topic of conversation at the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow this fall, where countries will assemble to try to advance the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Van der Ploeg says there’s “momentum” heading into the meeting, but he doubts the discussions will dwell on the painstaking planning and financing it will take to make things happen. “The question is,” he says, “how do you translate it into real policies?”

Disclosure: Andrew Lo serves on the Board of Trustees of Annual Reviews, which publishes Knowable Magazine.

Editor's Note: This article was updated October 4, 2021, to correct the name of the MIT school where Andrew Lo is on faculty. It is the MIT Sloan School of Management, not the Sloan School of Business.