Nature interrupted: Impact of the US-Mexico border wall on wildlife

Scientists on both sides of the border are working to understand how the barrier is affecting the area’s biodiversity. Meanwhile, communities try to save animals left without access to water.

Support sound science and smart stories

Help us make scientific knowledge accessible to all

Donate today

In a vast stretch of the Sonoran Desert, between the towns of San Luis Río Colorado and Sonoyta in northern Mexico, sits a modest building of cement, galvanized sheet metal and wood — the only stop along 125 miles of inhospitable landscape dominated by thorny ocotillo shrubs and towering saguaro cactuses up to 50 feet high. It’s a fonda — a small restaurant — called La Liebre del Desierto (The Desert Hare), and for more than 20 years, owner Elsa Ortiz Ramos has welcomed and nourished weary travelers taking a break from the adjacent highway that runs through the arid Pinacate and Grand Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve.

A report released by the US Government Accountability Office states that the construction of the wall on the US-Mexico border during President Donald Trump’s administration caused the destruction in Arizona of numerous saguaros, giant cacti like the one in the photo that can grow up to 50 feet tall and live more than 150 years.

CREDIT: IVÁN CARRILLO

But the dedication and care of this petite woman go beyond her simple menu. Every two weeks, she pays out of pocket for a 5,000-gallon tank of water to distribute to a network of water troughs strategically placed in the area. By doing so, she relieves the thirst of bighorn sheep, ocelots, pronghorn, coyotes, deer and even bats that have been deprived of access to their natural water sources.

“The crows come to the house and scream to warn us that there is no more water ... it’s our alarm,” says Ortiz Ramos in her distinct northern Mexico accent. Her words sound straight from an Aesop’s fable, but they take on stark realism in this spot. Covering large parts of Arizona, California and the Mexican states of Baja California and Sonora, the Sonoran Desert — along with the Lut Desert in Iran — was catalogued in 2023 as having the hottest surface temperature on the planet, at 80.8 degrees Celsius (177 degrees Fahrenheit).

Through narrow steel bollards 3.5 inches apart, I observe lush vegetation surrounding the Quitobaquito spring on the other side of the border. “This vital source supplies both humans and animals over an area of more than 1 million hectares,” Federico Godínez Leal, an agronomist from the University of Guadalajara, explains to me. But now this crucial water source is restricted to the US side due to the construction of the border wall, and I have come with him here to understand the consequences. Godínez Leal and his team have been documenting the stark difference between each side: Their poignant photographs show skeletons of wild boar, deer and bighorn sheep lying on Mexican soil.

Federico Godínez Leal, who coordinates the Maggol Foundation’s rescue work to help wildlife in the Mexican Sonoran Desert, inspects the remains of a bighorn sheep that probably died from lack of water.

CREDIT: ÓSCAR FEDERICO GODÍNEZ N.

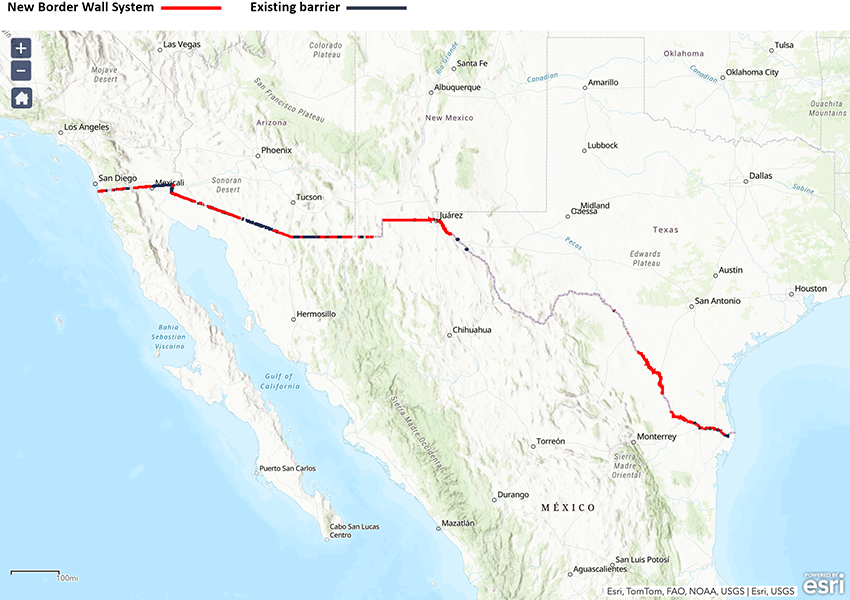

Between 2017 and 2021, the US government installed more than 450 miles of border barriers — steel structures between 18 and 29 feet high, spaced less than 4 inches apart — in the western end of the more than 1,900 miles of border between Mexico and the United States, stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. Of these 450 miles, 81 percent were replacements of existing vehicular or pedestrian barriers — but which, due to their design, allowed some passage of animals across the border. The rest were new barriers.

Before its construction, scientists on both sides of the border had warned about the impact that the wall could have on the animals of the area, and they are now working to understand the consequences. In turn, villagers in some spots on the Mexican side of the border have organized to try to alleviate the thirst of many animals that have been left without access to water.

The transformation of a border

The border between Mexico and the United States, defined after the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) in which Mexico lost more than half of its territory, is frequently in the news for the flow of migrants from the south and for criminal activities, especially in neighboring cities like Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez. But for more than a century, the border was a place of peaceful transit between the two nations, barely delineated by 258 concrete obelisks that still stand today, numbered chronologically from east to west and placed exclusively as a visual reference.

Between 2017 and 2021, the US government built over 450 miles (730 kilometers) of border barriers (marked in red on the map). Of those, 81 percent replaced preexisting vehicle and pedestrian barriers, which wildlife can more easily traverse.

CREDIT: US CUSTOMS AND BORDER PROTECTION

The situation changed drastically in 1994, when, citing increased illegal migration and drug trafficking, the US government implemented Operation Gatekeeper, installing the first barriers in urban areas.

That was the start of an escalation that would intensify during two key moments. First came the approval of the Secure Fence Act of 2006, and the construction of 700 miles of barriers by 2015. Some were pedestrian fences: panels of vertical bollards up to 18 feet high, made of concrete-filled steel, spaced 4 to 5 inches apart, designed to impede the passage of people on foot. Others were Normandy-type barriers: large steel beams intersecting and anchored to the ground in the shape of an X. At 3 feet high and with large gaps between the beams, they were intended to block the passage of vehicles but allowed the passage of people and small animals.

The most critical moment happened on January 25, 2017, just days after Donald Trump assumed the presidency of the United States. To materialize as soon as possible the border wall he had promised in his campaign in order to curb migration from the south, he issued Executive Order 13767, which initiated the wall’s planning and design, as well as the construction of several segments with funds available at the time.

Between 2006 and 2015, the US government erected pedestrian fences (top left) and Normandy-style fences (top right) along the northwest Mexican border. Between 2017 and 2021, a new type of taller and more compact infrastructure was built; these stretches were also reinforced with concrete levees, lighting systems and patrol roads.

CREDIT: UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTABILITY OFFICE (GAO)

Then the declaration of a national emergency due to the border crisis in February 2019 spurred large-scale construction and the use of significant Department of Defense funds and other federal resources. This allowed the project to circumvent critical environmental regulations such as detailed environmental impact analyses and consideration of less harmful alternatives to the proposed construction.

Construction went ahead despite scientists’ prior warnings about the impact on biodiversity. In an article in the journal Bioscience titled “Nature Divided, Scientists United: US–Mexico Border Wall Threatens Biodiversity and Binational Conservation,” scientists from both nations raised this alarm: The wall, along with its associated infrastructure, such as roads and lighting systems, would devastate vegetation and cause the death of animals directly or indirectly through loss of habitats and fragmented ecosystems. It also would induce erosion and modify hydrological processes and patterns of wildfire activity, they wrote.

Published in October 2018, the article estimated that constructing the border wall would affect 1,506 native animal and plant species along the border, including 62 that were in some category of risk or endangerment according to the IUCN Red List, a globally trusted inventory of species under threat.

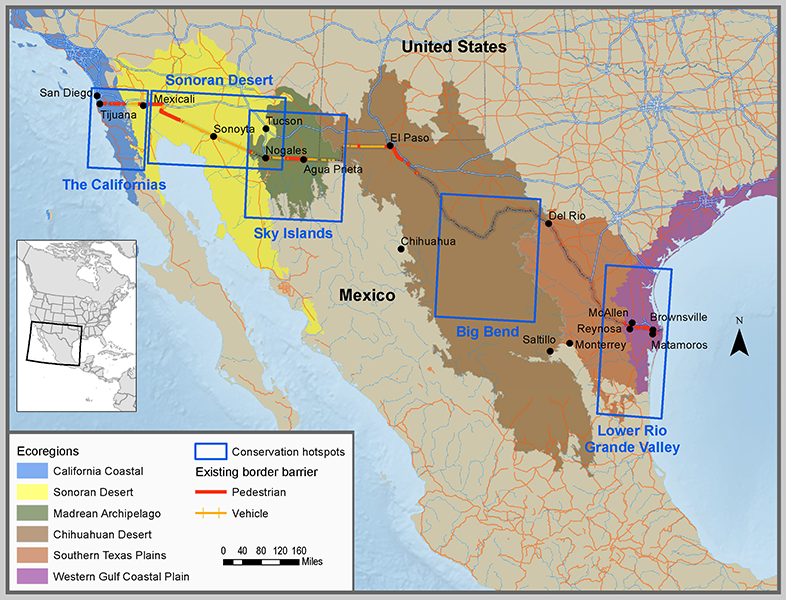

The US-Mexico border includes six ecoregions — geographic areas that share characteristics in terms of climate, geology, hydrology, flora and fauna. Within them are key conservation hotspots (indicated by blue rectangles on the map) such as the Sonoran Desert, the Madrean Archipelago and the Chihuahuan Desert.

CREDIT: R. PETERS ET AL / BIOSCIENCE 2018

Nevertheless, construction companies advanced along the border through urban, rural and remote areas, dividing ecoregions along the way: slicing through the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts as well as the Madrean Archipelago, known for its sky islands — mountains isolated by deserts that are home to numerous endemic species. The new wall also disconnected parks and nature reserves (the border is home to 25 national protected areas on the US side and eight on the Mexican side, in addition to several private reserves).

The wall also split communities. “On both sides of the border, people have made a living from cattle ranching, some for generations,” writes Rurik List, a biologist at the Autonomous Metropolitan University of Mexico. “Before the wall, they attended the parties and meetings of the neighbors on the other side, crossing through the gates they maintained to return the cattle of the neighbor who had crossed the fence.” The wall also divided in two the historic lands of the Tohono O’odham people, who have long lived along the border between Mexico and the United States. One of its leaders, Verlon M. Jose, expressed to media the pain that the split had caused him: “It feels like if someone got a knife and dragged it across my heart.”

At the start of the following US administration, in 2021, President Joe Biden halted the national emergency and thus construction of the wall. That left many of the sections unfinished. Of the 456 miles of barriers installed, only 69 miles included all the required components, such as sensors and patrol paths. It also stopped restoration work and erosion control measures, including sections that lack gates that can open during heavy rains to let water to pass through and prevent flooding in regions along the border.

In October 2023, the construction of an additional 20 miles of wall was authorized, as its funding had been approved during Trump’s presidency.

That same year, a report by the US Government Accountability Office detailed the erosion caused by contractors disturbing extensive mountainous areas for barrier installation and construction of access roads, leaving slopes unstable and susceptible to collapse.

The impact of the wall on biodiversity

For nearly three years, Ganesh Marin Mendez, an ecologist at the University of Arizona, has been leading a study that seeks to understand how the presence of the fence affects the mammal population. His work focuses on the biodiversity around the Cajón Bonito stream (located 51 miles east of the town of Agua Prieta, Sonora) and evaluates whether mammals around the Arizona-Mexico boundary cross the border wall and the busiest highway in the area, Federal Route 2. Through camera traps, infrasound recorders and the study of environmental DNA in the creek, the team has identified the presence of 52 species of mammals, including jaguars, ocelots, bats, porcupines, and beavers. The investigation is in process, but the preliminary results, he says, show that there has been a notable decrease in the presence of animals in the areas near the wall and the highway.

Ganesh Marin Mendez and his team at the University of Arizona installed 100 camera traps and low frequency recorders to monitor animals at the Cajon Bonito stream, the border wall and Federal Route 2, in the frontier between Sonora and Arizona. The video shows a mountain lion and the border wall in the background.

CREDIT: BORDERLANDS ECOLOGY & APPLIED RESEARCH / BEAR PROJECT

It is clear that the wall has divided populations of animals that used to inhabit a transboundary territory. A study published in 2010 in Conservation Biology anticipated as much. The research focused on the genetic diversity and population movements of two species in the Arizona-Sonora border region whose existence in the area may depend on transboundary movements: ferruginous pygmy owls (Glaucidium brasilianum) and desert bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis mexicana). Data were collected between 2002 and 2005, before there was a border fence in the area studied.

The results revealed that the ferruginous owl, which flies at an average height of 4.6 feet above the ground, could be severely limited by fences taller than 13 feet, which is the maximum height that only some of the birds can reach — the current wall exceeds 16 feet. Although these birds are common on the Mexican side of the border, the Arizona population is at risk of extinction and depends on migration from the south for its recovery and survival.

The study also reported potential effects on bighorn sheep populations. These animals live in small groups in mountainous areas separated by valleys, but there is contact between the groups. Through genetic analysis, the researchers determined that nine populations living in the mountains of Sonora are related to groups in Arizona. They warned that the construction of an impermeable fence could cut off contact between groups, significantly reducing gene flow. Such isolation could lead to rapid genetic divergence and loss of diversity, making recolonization after local extinctions difficult.

Other species such as the Sonoran pronghorn (Antilocapra americana sonoriensis), jaguar (Panthera onca), desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii), mountain lion (Puma concolor) and black bear (Ursus americanus), which need large open areas to roam, as well as contact between populations to maintain genetic diversity, would also be affected, the study warned.

Movement through habitat is essential for the survival of many species, such as the black bear, Sonoran pronghorn, mountain lion and desert tortoise, which live in the Sonoran Desert. The border wall prevents these and other animals from moving freely.

CREDITS, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: BOB THOMSON, ROBERTO GONZÁLEZ, COUGARMAGIC, JOHNK39 / iNATURALIST

This type of impact could extend to key species such as the Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), a top predator whose survival is an indicator of ecosystem health. With binational conservation efforts underway after its near extinction due to livestock expansion, the free population in Mexico — reintroduced in the last two decades — is only about 40 individuals. These wolves must connect with the wolf population in the United States to ensure the necessary genetic variability, researchers say. List says that there has been at least one documented case of a wolf attempting to cross from the United States into Mexico being stopped by the wall in Janos, Chihuahua.

The wall is not only fragmenting transboundary animal populations, it also will hinder some species from moving to adapt to climate change. A 2021 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences projects that by 2070, under a scenario in which carbon dioxide emissions remain high, 35 percent of mammals and 29 percent of birds will see half of their suitable climate habitat move to countries where their species aren’t currently found. The necessary movements for such species to relocate to their ideal climatic niches will be hindered by border barriers, the authors warn.

In the case of the US-Mexico border wall, the study found, affected species include the Sonoran pronghorn, jaguar, mountain lion, ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) as well as the Montezuma quail (Cyrtonyx montezumae), the Tarahumara frog (Lithobates tarahumarae) and the desert tortoise. In this context, the ability to work on conservation across political borders takes on greater importance, the authors note. “Safeguarding the Earth’s biodiversity under climate change will require far greater transboundary collaboration of local communities, conservation organizations and national governments than is currently needed,” they write.

Species diversity is sustained by a variety of processes, many of which depend on the ability of animals to move freely across the landscape. Examples include the Tarahumara frog, which once inhabited southern Arizona but is now found only in Mexico, and the Montezuma's quail, whose northern populations often migrate to the Mexican side during the winter.

CREDITS: TOM KENNEDY (LEFT), SALVADOR JAUREGUI (RIGHT) / iNATURALIST

On this note, Charles Chester, a specialist in global environmental policy at Brandeis University, flags a little-discussed impact of the border wall: its symbolic value. The coauthor of an article on the importance of environmental and conservation policies for species that cross borders in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources, Chester notes that the wall represents not only a physical barrier but also a symbolic obstacle that negatively affects relations and joint work between conservationists from both countries. It hinders conservation initiatives that were previously carried out with smoother collaboration.

Among these initiatives is the Duck Stamp program, implemented in the US since 1934, which funds the conservation of migratory waterfowl habitat through the sale of wetland hunting licenses in the US, Canada and Mexico. Also included are joint efforts to protect the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus), which makes an annual journey of more than 4,900 miles between Canada and Mexico, or the Brazilian free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), which plays a crucial role in pest control for cotton crops in the United States and depends on conservation areas in Mexico for its reproduction.

Back to Quitobaquito

Quitobaquito, those waters I saw through steel borders when I visited with Godínez Leal of the University of Guadalajara, is not just a spring: It is a vital connection to the past and an essential oasis for wildlife in this vast desert. Seen from the air with a drone camera, it has the shape of an arrowhead, about 20 meters longer than an Olympic-size swimming pool at its maximum length. The oasis is on what was historically called El Camino del Diablo (the Devil’s Highway) and its waters have quenched the thirst of people and animals for millennia. But now the territorial division has cut off the Mexican side.

The Quitobaquito spring, a main source of water for the fauna in the Sonoran Desert, has been continuously occupied by people for approximately 16,000 years. Ancient cultures traveled through this region to obtain salt, obsidian, seashells and other goods from the salt flats of Sonora, Mexico. The spring is also part of the historic lands of the Tohono O’odham people.

CREDIT: NPS PHOTO

Godínez Leal says this has imperiled the fauna of the Pinacate and Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve, which he directed between 2004 and 2017 and was named a World Heritage Site in 2013. Animals that historically migrated in search of sustenance now find their passage cut off. Water availability is particularly reduced, forcing wildlife on the Mexican side to rely exclusively on rainwater in two brief and increasingly uncertain annual seasons. There is less vegetation and less food, triggering a domino effect on the entire food chain.

The dire situation prompted Godínez Leal and leaders from the Toboyori and Vicente Guerrero cooperative farms called ejidos, which make up about 90 miles of the reserve’s border with the US, to take matters into their own hands. They created the Maggol Foundation to monitor the impacts of the fence on biodiversity and initiate an emergency program.

The job of hauling water to the desert, done by volunteers such as Elsa Ortiz Ramos, the owner of the desert fonda, is monumental. The water must be transported from Sonoyta or from San Luis Río Colorado, towns some 60 miles away in opposite directions, through remote rocky territories and distributed in troughs that have been built or repaired. It would be easy to get discouraged, says Héctor Quiroz Orozco, the ejidatario — holder of a share in common lands — and Maggol Foundation volunteer. He laments the decreasing presence of animals. “You don’t find tracks anymore, you don’t hear the animals anymore,” he says. “It seems that no one cares.” And there is urgency: Godínez Leal warns that the region’s major fauna could disappear within four or five years.

Elsa Ortíz Ramos is a volunteer for the Maggol Foundation. Every two weeks, she drives her truck through the Mexican Sonoran Desert to bring water to the watering troughs and try to avoid that the animals in the area die of thirst.

CREDIT: IVÁN CARRILLO

After completing a grueling day of filling water troughs in the desert, Ortiz Ramos takes a portable loudspeaker from her truck, along with some candles and a glass of water. She reverently arranges the candles in the shape of a cross and places the glass of water at its center.

Then she cranks the speaker to top volume and presses play. A recorded voice resounds through the vastness of desert, reciting the Lord’s Prayer, “Our Father.” Ortiz Ramos closes her eyes and begins to pray, forming crosses with her fingers. This act, she explains, is a ritual of thanksgiving for life and a tribute to the souls who have perished in their arduous journey through the desert.

In September 2023, the UNESCO World Heritage Convention requested the two nations collaborate on an urgent action plan to assess and mitigate the impacts of the wall and restore connectivity in the ecosystem. The delegation that visited the area in February 2024 seeks to motivate action to prevent the Pinacate and Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve from becoming a World Heritage Site in Danger.

A few meters from where we are, we can see food wrappers and empty water bottles next to the remains of an improvised campfire. One would think that in the face of this wall, human migration would have been banished from the area. “On the contrary, it has increased,” says Godínez Leal. “They have found different ways to overcome the wall, either going underneath or over it.”

In the current US presidential campaign, Donald Trump is again promising strict anti-immigration measures — among them, to finish building the border wall. It’s an infrastructure whose effectiveness can be questioned with a single figure: In December 2023, the US Border Patrol apprehended nearly 250,000 migrants crossing into the United States from Mexico, the highest monthly total on record.

The border wall seems to have stopped everything but human beings.

Article translated by Debbie Ponchner

Editor’s note: This story was updated on June 28, 2024, to clarify the references to how the border wall has affected the Tohono O’odham people.

This article is part of Knowable Magazine’s series exploring the work of Latino scientists and emerging research affecting the US Latino community, presented in English and Spanish, and supported by the Science and Educational Media Group at HHMI. Iván Carrillo is currently a fellow of the Earth Journalism Network. This story was produced as part of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network’s 2024 Reporting Fellowship.

10.1146/knowable-062724-2

TAKE A DEEPER DIVE | Explore Related Scholarly Articles