Getting along with grizzly bears

In rural Alaskan and Canadian communities, reducing conflict between people and their wild neighbors means both species must change their behavior

Support sound science and smart stories

Help us make scientific knowledge accessible to all

Donate today

Treading carefully through yellowing aspen forest in southeastern British Columbia, wildlife scientist Clayton Lamb parts undergrowth with his arms as he looks for a sturdy tree to tether his bear trap to. A tantalizing scent trail has been laid to lure an animal that can range over a thousand square kilometers to this precise spot, outside of the town of Fernie. Lamb’s colleague, wildlife technician Laura Smit, drizzles rotten cow blood through the woods from a red plastic gas can. To human noses, the stench is revolting. To a grizzly bear on a mission to fatten up for winter, it is tantalizing.

A researcher at the University of British Columbia Okanagan, Lamb has spent days with Smit driving up and down this valley in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, selecting sites, creating scent trails and constantly checking remote cameras for alerts that a trap has been triggered. Night passes. No bears. Most of the next night passes uneventfully, too, until 4:31 a.m., when one camera detects activity. Lamb texts: “Got a grizz.”

As sunrise bathes the valley in orange-gold light, Lamb and Smit turn onto a dirt road and climb switchbacks to where a small female grizzly has been drowsily dozing against its tether tree, one foot secured in the trap, a smooth-edged harness looped around its leg like a handcuff. One well-placed shot from Lamb’s dart gun out the truck window delivers a dose of xylazine and Telazol tranquilizer. A few minutes later, the bear is slumped in a drugged stupor.

Lamb and Smit approach with their gear, check vitals and begin measuring, sampling and hoisting the grizzly’s anesthetized body into the air in a sling winched to a tree. Weighing 87 kilograms (192 pounds), typical for a grizzly female that is not fully grown, she is estimated at 4 years old.

As part of their study of bear behavior, scientists Clayton Lamb and Laura Smit work in the Canadian Rocky Mountains near Fernie, British Columbia, to measure and place a tracking collar on a roughly 4-year-old female grizzly, tagged as EVGF129, and nicknamed Lesley.

CREDIT: LESLEY EVANS OGDEN

Reaching age 4 in this landscape is a remarkable achievement. The habitat is crisscrossed by roads, railways, coal mines, ski resorts, farms, rural properties and small towns. “This isn’t a national park,” Lamb says. But as biologists study how bears can coexist with people here and elsewhere, they are learning that coexistence is a two-way street: Bears change their behavior in order to survive, but to share this habitat harmoniously, the people living here must be willing to change, too. Surprisingly straightforward and relatively inexpensive measures, researchers are learning, can make a huge difference in reducing conflict and saving bear lives and human grief.

Grizzly death trap

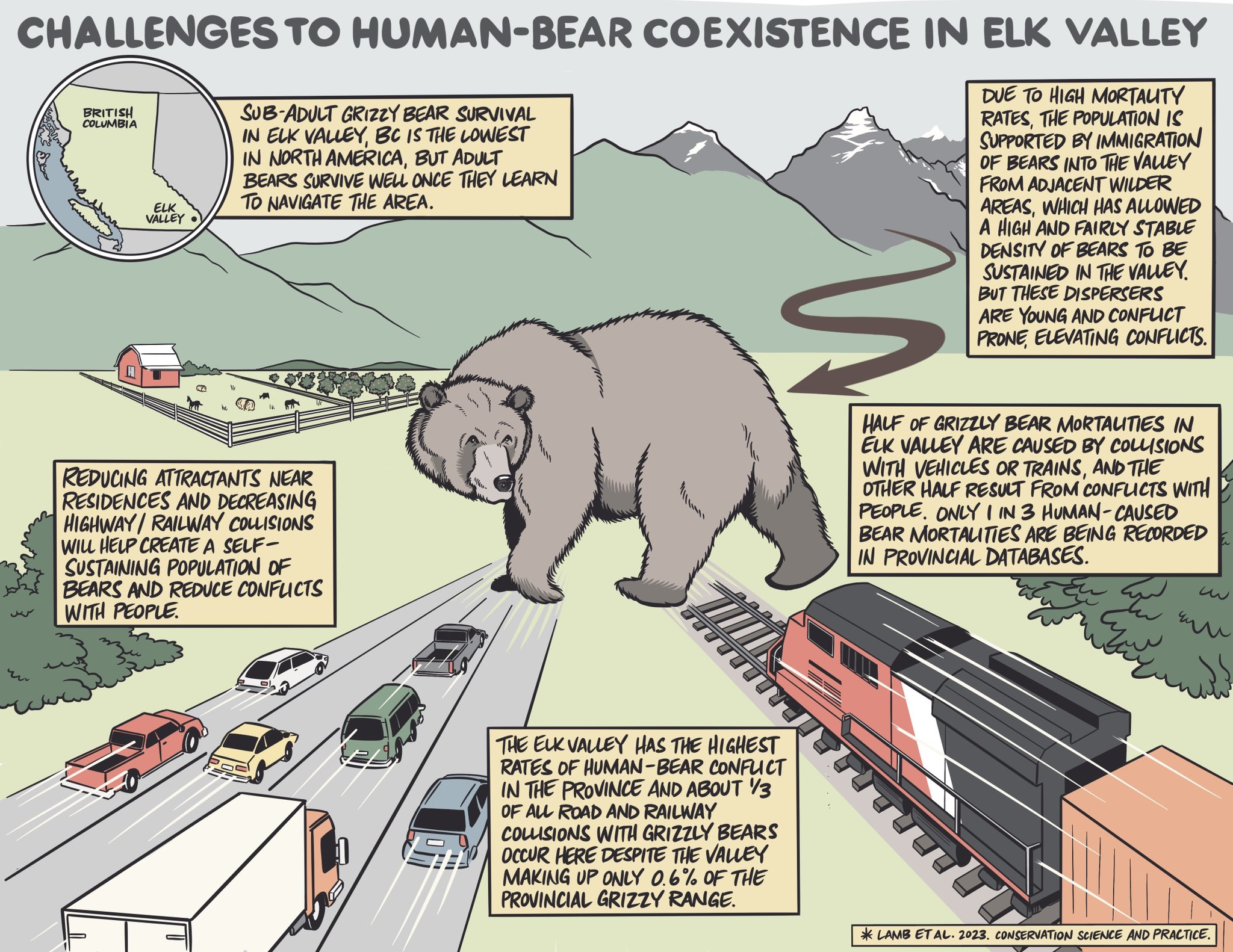

The female, newly recorded as EVGF129, has already beaten the odds. Almost three-quarters of all young females that grow up in the Elk Valley die younger. In fact, after GPS-collaring 70 bears between 2016 and 2022, Lamb and colleagues found that survival rates for young grizzlies in the Elk Valley are the lowest recorded in North America and an order of magnitude lower than elsewhere in BC.

Of the 14 collared bears that died during that study, just one died of natural causes. Conflict with people caused six deaths, perhaps seven. Collisions with road vehicles or trains killed another six; one cause of death remains a mystery. The level of conflict in the Elk Valley is 10 times higher than the average for the province. It’s “a death trap for young bears,” says Lamb.

And it’s one not fully reflected in government reports. Were it not for Lamb’s GPS collars, the deaths of more than half of the grizzlies he tracked would have gone undetected. The implication is that there are many unreported deaths among uncollared bears, too.

Paradoxically, despite the high death rate in the Elk Valley, the number of grizzly bears in the region is stable. Although deaths exceed births here, an average of seven grizzlies per year wander in from neighboring regions in search of the same things that draw people to the valley — space to live and food for their families.

Intense pressure on young bears in this dangerous landscape means a steep learning curve and necessary changes to their behavior. To survive, many adopt a key strategy — becoming significantly more nocturnal to avoid human encounters. Nocturnality, Lamb and colleagues found, increased this population’s annual survivorship by 2 to 3 percent. Only bears in human-bear coexistence landscapes showed this nocturnal shift. Bears in wilderness areas did not.

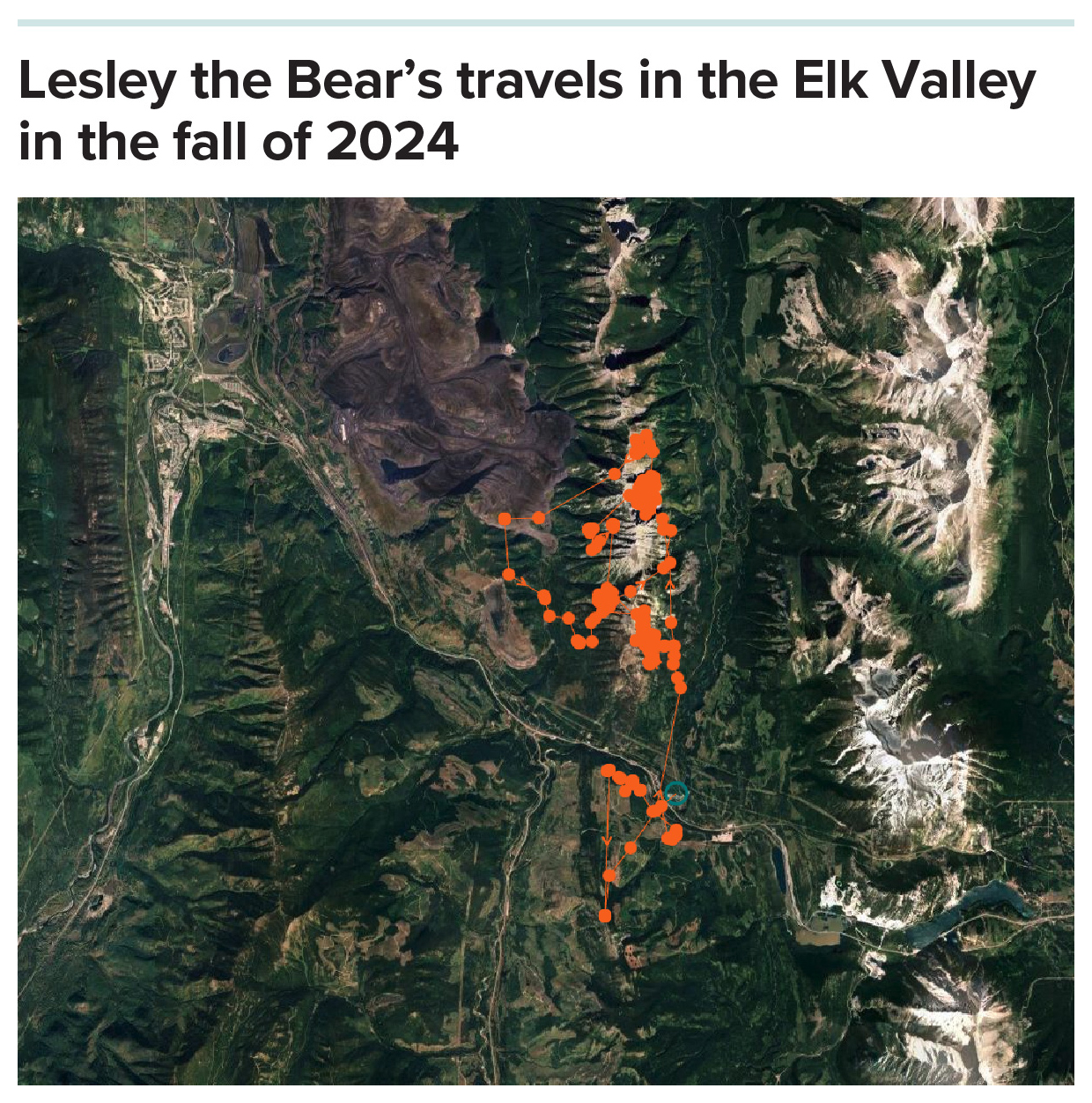

This map of Elk Valley shows where Lesley (Bear EVGF129) wandered in the autumn of 2024 before she settled down to den for the winter on November 1. Though her tracks show she is mainly a mountain bear and hasn’t yet been involved in human conflicts, she exists in a landscape crisscrossed by hazards like roads, railways, farms and small towns. The orange dots show Lesley’s locations as determined from her tracking collar.

CREDIT: COURTESY OF CLAYTON LAMB

But for grizzly bears and people to coexist in the long run, it’s not just the bears that need to alter their behavior. Historically, grizzlies were shot, trapped and poisoned across much of the continent, reducing them to just 45 percent of their former North American range by the 1970s, with the remnants almost entirely in Canada and Alaska. Today, attitudes are shifting from human domination of nature toward mutualism — and that means learning to get along with our neighbors.

Addressing the human side of human-wildlife conflict might seem like a no-brainer. But across the history of conservation science, human behavior change has been tremendously under-researched and under-resourced, notes Diogo Veríssimo, of the University of Oxford, England, who heads the International Union for Conservation of Nature Behaviour Change Task Force.

Since all the major threats to biodiversity stem from human activity, it will be impossible to prevent extinctions without changing our own behavior, says Veríssimo, a conservation marketer who coauthored a look at human-wildlife coexistence in the 2024 Annual Review of Environment and Resources. “Coexistence is fundamentally about the relationships between people and less about the animals,” he says.

That’s why Lamb and partners such as the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, a cross-border program aimed at connecting landscapes to boost biodiversity across a broad reach of Western Canada and the US, have been spearheading a community coexistence plan for the Elk Valley since April 2024.

In Canada’s Elk Valley, Clayton Lamb and colleagues found that survival rates for young grizzlies are the lowest recorded in North America and an order of magnitude lower than elsewhere in British Columbia. This is predominantly due to human conflicts.

CREDIT: RUSH STUDIOS

Fence bears out

With snow still clinging to mountainsides and bears still asleep, some 30 people have shown up in a converted Fernie railway station to discuss grizzly bear coexistence. Lamb is one of several scientists here. Also at the meeting are representatives from the Ktunaxa Nation, government and industry, as well as retired park rangers, city planners, conservation groups, a wildlife technology company and residents. All share an interest in the gnarly problem of how to live alongside North America’s second-largest land predator (exceeded in size only by the polar bear).

Coexistence consultant Gillian Sanders has traveled to this meeting too. She works around the town of Meadow Creek, five hours’ drive northwest. When she first moved to the area and started studying Meadow Creek’s relationship with grizzly bears, she also brought her honeybees. Realizing that honey was a major bear temptation, she installed an electric fence to protect her hives. When that proved effective, she realized it would also work around apple trees, chicken coops, livestock pens and any other attractant. So over time, the use of electric fencing, and the expertise needed to install and maintain it, has spread through her community and the surrounding region, with 535 electric fences installed to date.

Solutions are poorly researched and studying them has been much less of a priority than research on bear movements, demographics and behavior, but an international review of published studies suggests that this straightforward move — installing electric fencing — reduces damage to infrastructure by 80 to 100 percent. It was the most effective of all of the interventions evaluated, including chemical and acoustic deterrents, translocation of bears, isolation of attractants like food and garbage, vegetation care and lethal control (shooting).

Before Sanders moved to Meadow Creek, getting along with the bear neighbors had been a challenge. Tracy Remple, who runs a small farm there, notes that in times past, bruin thieves would brazenly swipe ripe apples off trees, rip carrots from vegetable gardens, raid bird feeders, prey on farm animals and break garage doors to steal trash. Decades ago, trash at the local landfill was an even bigger problem. Remple remembers taking town visitors to the dump where, for entertainment, they would watch grizzlies chow down on diapers and soaker mats from meat trays.

Raised in a Mennonite family, as a kid Remple watched her dad shoot grizzlies from their front porch. As a young adult, Remple left for city life, but 10 years later, returned. “I wanted a homestead. I wanted fruit trees. I wanted chickens. I wanted goats. I wanted all of the things that bears love to eat.” And she wanted it without shooting bears. “What could possibly go wrong?” she laughs.

On one occasion, things did go badly wrong. Late one night a grizzly tried to steal her prize ram. Caught in the act, the bear fled, leaving the dead ram dangling atop the farm fence, and leaving Remple shaken. In recent years, however, thanks in large part to Sanders’s work and the work of the not-for-profit charity WildSafeBC, the idea of human-bear coexistence has taken hold. Remple now has electric fencing surrounding her livestock paddock.

Around town, there are now electric fences around apple trees, chicken coops, livestock paddocks, beehives, vegetable gardens, composts, and sections of the government-run kokanee salmon spawning channel so that bears can fish and humans can monitor kokanee in safety. Even Remple’s father, who once shot every bear he saw, eventually put electric fencing around his chicken coop.

Remple has also adopted another simple behavior change: She carries bear spray when she’s out in her farmyard. A study in Alaska reported that bear spray stops “undesirable behavior” 92 percent of the time for grizzly bears, with 98 percent of people carrying sprays uninjured in close-range bear encounters. Defusing such close encounters can help reduce risk for humans — and for bears too, by reducing the need for government conservation officers to shoot bears deemed a public danger, a scenario that led to the death of 24 grizzly bears in BC in 2024.

Tracy Remple, a farm owner in Meadow Creek, British Columbia, wears bear spray on her hip in a holster as she points to her livestock paddock enclosed by an electric fence. Such fences help to minimize the potential for conflict between grizzly bears and people despite sharing similar needs for food, shelter and habitat.

CREDIT: LESLEY EVANS OGDEN

Shifting attitudes about coexistence

But changing local attitudes takes work, because not everyone is easily swayed toward a coexistence mindset. Conservation scientist Courtney Hughes, who studied human-bear coexistence for her doctorate at the University of Alberta and continues to work on human-wildlife conflict issues in Canada and Africa, suggests there’s often misunderstanding in the public realm about what “coexistence” means.

Her work studying public attitudes highlights that the participation of local and Indigenous communities in human-wildlife conflict produces better conservation outcomes than the “parachute scientist” coming in and telling locals what to do. “There’s a bit of ego in the Western scientific conservation mindset,” says Hughes. That can get people’s backs up.

Indeed, coexistence is more nuanced than applying hard science to a problem. It relies on relationship-building, patience and trust. In the predominantly Indigenous Kitasoo Xai’xais remote coastal community of Klemtu, BC, for example, ecotourists visit with the hope of seeing bears but locals also need to live harmoniously alongside them. Wildlife coexistence coordinator Sierra Hall says that in developing coexistence solutions, “we were starting from scratch because we didn’t really find anything off the shelf that made sense for a community like ours.”

In Meadow Creek, British Columbia, managing the coexistence of humans and grizzly bears requires a year-round effort, but especially when food sources like spawning salmon, fruit trees and livestock bring them into potential conflict. Here, signage tries to keep people away from places where grizzly bears commonly feed.

CREDIT: LESLEY EVANS OGDEN

In consultation with the community, including local elders, she has set up clearly signposted areas of bear-only, human-only and shared coexistence zones, improving waste management with bear-resistant bins and installing cleaning tables on the town dock. Freshly caught fish can be cleaned and gutted there, with their smelly entrails disposed of in deep water rather than attracting bears as they would if left on land.

Coexistence is catching on in the Elk Valley too. In a government-landowner cost-sharing scheme supported by conservation groups and industry, nine electric fences were erected in 2024. Lamb and BC wildlife biologist Sean O’Donovan show off one new electric-fenced yard in a former conflict hotspot a few miles outside Fernie. Now the landowner can watch their birdfeeder without fear of a grizzly feeding there too.

Just down the highway, not far from where Lamb collared Bear EVGF129, electric fencing has also secured another conflict hotspot. Tracking collared bears revealed that bears were being lured into traffic danger by a roadside pit where the Ministry of Transportation was dumping roadkill. Now all it takes is one zap, and bears usually don’t return. There hasn’t been a bear killed by vehicles near the pit since the fence was built, Lamb says.

Hughes notes that we don’t rigorously evaluate what’s working in coexistence programs. That needs to change. “There is just so much more to learn,” she says. “And we all need to listen more and actually hear what people are saying.”

As for Bear EVGF129, which Lamb and Smit have nicknamed Lesley, she has survived yet another winter in this dangerous place. Lamb’s GPS shows that while she’s crossed the road twice since being tagged, she’s mainly a mountain bear, favoring ridgetops.

She has developed the street smarts to survive as well as can be expected in her world fraught with human hazards. Now Lesley’s future depends not only on her own coexistence decisions but also on ours.

Editor’s note: This article was updated on May 22, 2025, to correct the figure for the decline of grizzly bears in North America. They declined to 45 percent of their original range, not 55 percent. This article was updated on May 7, 2025, to correct the credit for the graphic illustrating challenges to human-bear coexistence in the Elk Valley. It was created by Rush Studios.

10.1146/knowable-050625-1

TAKE A DEEPER DIVE | Explore Related Scholarly Articles