UPDATE, June 5, 2019: On June 3, California regulators decided against requiring carcinogenic labelling on coffee in the state. According to an Associated Press report, the Office of Administrative Law granted coffee an exemption after determining that no studies linked coffee to increased cancer risk. The FDA and IARC had recently weighed in on the potential rulemaking decision.

Most of us think of coffee as a morning essential, not a cancer-causing hazard. So the nation got a jolt after a California judge made a final ruling in May that Starbucks and other coffee sellers must inform customers about carcinogenic chemicals in their brews.

The ruling stemmed from a court case invoking Proposition 65, a state law that requires warnings if products or places contain certain types of hazardous chemicals. But the implications reach far beyond the Golden State. California has the sixth-largest economy in the world, so manufacturers of consumer goods worldwide try to abide by Prop. 65 regulations.

Here’s a primer on how hazardous chemicals get listed and regulated, the ongoing coffee case — yes, it’s still not over — and what might be labeled or litigated next.

Why will there be signs next to Starbucks registers warning that coffee contains chemicals that cause cancer and birth defects?

In late March, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge ruled that cups of coffee sold to consumers would fall under the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act — Prop. 65 — which was passed by a ballot vote of California residents in 1986. The judge made a final ruling May 7.

A Proposition 65 sign in a San Francisco Starbucks warns of acrylamide in coffee and baked goods. It is located by the sugar and creamer; Starbucks was sued to place the warning at the point of sale.

CREDIT: ROBERT ALEXANDER / GETTY IMAGES

The law applies because roasted coffee beans — and beverages brewed from them — contain acrylamide, which is on Prop. 65’s state-regulated list of chemicals “known” to cause cancer, birth defects or reproductive harm. If a product contains any of the list’s approximately 900 chemicals, it must be labeled to warn consumers, or the chemical must be removed or reduced to levels that Prop. 65 regulators consider safe.

In April 2010, an organization called the Council for Education and Research on Toxics (CERT), which is located at the same address as the Long Beach law firm that represented it and that specializes in litigating such cases, sued about 160 companies, including Starbucks Corp. and the convenience store 7-Eleven, to force them to label their coffee with Prop. 65 warnings. The Los Angeles judge ruled that companies failed to demonstrate that the health benefits of coffee outweighed the risks posed by acrylamide, which include cancer and developmental and reproductive harm. 7-Eleven and some other companies have already settled out of court, agreeing to pay fines and place warning signs at the point of sale.

What does a Prop. 65 warning say and mean?

Up till now, generally words along the lines of: “WARNING: This product/area contains chemicals known to the State of California to cause cancer and birth defects or other reproductive harm. For more information go to www.P65Warnings.ca.gov.”

Proposition 65 warnings, like this one at Disneyland, have generally been very vague. New laws will require that the warnings name specific chemicals and their sources.

CREDIT: PATRICK PELLETIER / WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Such signs on a product, or in a restaurant, workplace, living space or parking garage, mean that the product or environment contains a chemical on the Prop. 65 list. A business must give “clear and reasonable warning” if knowingly exposing anyone, unless it can show the exposure falls under “safe harbor” levels: amounts determined by the state to pose no significant risk. (California set acrylamide’s safe harbor levels for cancer risk at 0.2 micrograms per day — its estimation of a dose that would risk cancer developing in 1 in 100,000 people, based on laboratory rat data. It set the level for reproductive risk at 140 micrograms per day.)

How does acrylamide end up in foods?

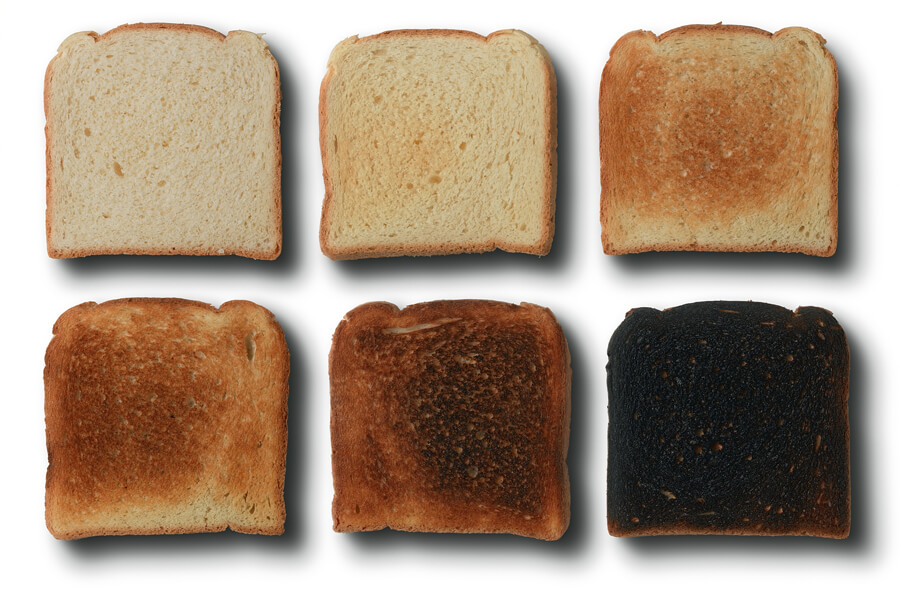

The chemical naturally forms in items such as baked goods, cereals, potato products and coffee during the Maillard, or browning, reaction, when the amino acid asparagine and a sugar combine in the presence of heat higher than 120 degrees Celsius (248°F).

“Any time you heat-process a food — toast a piece of bread, fry potatoes, bake a crust — sugars react with amino acids to form a whole catalog of chemicals. Acrylamide happens to be one of those chemicals,” says James Coughlin, a chemist in Aliso Viejo, California, and an independent consultant for the food industry. (Coughlin has consulted for the National Coffee Association and Starbucks in the past but is not currently working for any companies in the California court case.)

Acrylamide forms when bread is toasted and the amino acid asparagine reacts with sugars at high heat.

CREDIT: MILOS LUZANIN / SHUTTERSTOCK

When green coffee beans are roasted (typically at 180° to 240°C for about 15 minutes), more than 1,000 chemical compounds result as different sugars and amino acids combine and break down. “Coffee is the best example of the browning reaction gone wild,” Coughlin says. That swirl of chemicals gives coffee its complex tastes and aromas.

What is the evidence that acrylamide causes cancer or reproductive harm?

Acrylamide is used in industry and research to make polymers and is a neurotoxin at very high doses. It was found to be present in starchy, browned foods in 2002.

For cancer studies in 1986 and 1995, researchers fed rats high doses of acrylamide in their drinking water throughout their two-year lifetime. The highest doses increased rates of thyroid, testicular and breast tumors. In 2012, the US government’s National Toxicology Program (NTP), which tests environmental chemicals for potentially hazardous health effects, found similar increases in rats and mice. In male rats, the rate of thyroid tumors rose from 6 percent in rats fed no acrylamide to 25 percent in those fed the highest dose, for example. In females, the rate of a breast tumor rose from 33 percent without acrylamide to 65 percent for the highest dose.

(The NTP also assessed for reproductive harm in 2005 and found that while acrylamide causes slight increases in the incidence of low birth weight and less effective sperm in mice and rats fed high doses, there was no evidence that acrylamide exposure in people results in adverse reproductive effects.)

But experts say that the carcinogenicity of acrylamide in people is still up for debate. For one thing, says Coughlin, doses fed to rodents in these studies were extremely high — the equivalent of a 150-pound person drinking 11,000 to 136,500 eight-ounce cups of coffee per day. For another, population studies of workplace exposure to acrylamide have not found dose-related increases in any specific cancer or in overall cancer mortality.

An analysis of 25 epidemiology studies, encompassing 39,476 people, found no increased risk for 15 types of cancer when comparing people with average dietary intakes of acrylamide to those with daily intakes 10 micrograms higher (the amount in five eight-ounce cups of coffee). The authors concluded that dietary levels of acrylamide do not pose an increased risk of most types of cancer.

How do chemicals get on the Prop. 65 list?

In four ways. A chemical is automatically added if listed as a carcinogen or a developmental or reproductive toxicant by any of five authoritative bodies — the National Toxicology Program and three other US agencies, or the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). It only takes one agency to spark a listing; in the case of acrylamide, all five agencies list it as a probable human carcinogen.

A chemical may also be added if the California Labor Code deems it a cancer or reproductive risk, or if another agency requires a label. And it can be added if California-appointed State Qualified Experts — committees of researchers who specialize in cancer or developmental and reproductive biology — review the science and declare a chemical harmful by a majority vote.

Processed meats such as sausages were listed in 2015 by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as “carcinogenic to humans,” based on population studies that reported slightly increased rates of colorectal cancer in people who consumed the meats. Some speculate that processed meats will soon be added to Proposition 65's list of chemicals.

CREDIT: PIXABAY

That can be a tough call because the data are often imperfect, says toxicologist David Eastmond of the University of California, Riverside, a member of the Carcinogen Identification Committee. It bothers him that even if committees have reviewed a chemical and deemed it safe, another agency can override that work. “It’s not real often that you have differences,” he says. “But it makes you wonder, are you doing something consistent?”

Acrylamide was added to the Prop. 65 list in 1990 because both the IARC and the US Environmental Protection Agency (another of the triggering bodies) listed it as a carcinogen based on animal studies.

Are chemicals ever taken off the list?

Yes. Several have been delisted after studies showed them not to be carcinogens or reproductive toxins. (A reassessment can be triggered by State Qualified Experts, a state agency or petition by a member of the public.) One notable case is the artificial sweetener saccharin, which was listed as a carcinogen in 1989 because it caused bladder cancer in rodent studies, and was delisted in 2001. Decades of research showed that the way saccharin caused bladder cancer in male rats was not possible in humans.

Why are items listed when they might not be harmful to people?

The statute is designed to be precautionary and protective, says Claudia Polsky, director of the Environmental Law Clinic at UC Berkeley Law. “If it’s possible to decrease the levels of acrylamide in coffee, then people will have a lower exposure over their lifetime of a probable carcinogen,” she says. And the regulation, she adds, forces industry to innovate to find ways to remove or reduce harmful chemicals.

“Drinking coffee is still fine, and possibly even good for you,” she says. “But thanks to Prop. 65, coffee manufacturers might be able to make it even better.”

So is it safe to drink coffee or not?

The Food and Drug Administration, the European Food Safety Authority and Health Canada have all ruled coffee safe to drink, except for pregnant women, who should limit their intake.

A review of more than 100 epidemiology studies encompassing more than 21 million people found that coffee consumption has an overall health benefit, decreasing risks for a variety of diseases including cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, Parkinson’s disease and several cancers.

Coughlin says that roasted coffee beans or their grounds contain about 450 micrograms of acrylamide per kilogram, but brewed coffee contains only about 10 to 30 — a tiny dose compared to eating french fries or potato chips, which can contain acrylamide in the thousands of micrograms. The amount in an eight-ounce cup of coffee, 2 micrograms, is ten times the state’s safe harbor level of 0.2 micrograms a day. Acrylamide reacts with other proteins in the body as soon as it is absorbed, Coughlin adds, and is also detoxified by an enzyme called glutathione transferase.

Saccharin, found in products such as Sweet'N Low, was removed from Proposition 65’s list of risky chemicals in 2001. Decades of research showed it did not pose a cancer risk in people.

CREDIT: SIMON QIAO / FLICKR

“The bottom line for coffee is that while it does contain a small dose of acrylamide along with several other animal carcinogens, the overall beverage is loaded with antioxidants and has been shown to reduce the risk of several cancers,” he says.

Could it be made safer?

Maybe. After potato chip and french fry makers were sued by the California attorney general in 2005, they found ways to reduce acrylamide levels. Potatoes can be blanched to reduce sugar content, treated with an enzyme to remove much of the asparagine, or cooked for less time or at lower temperatures.

But coffee is trickier. Coffee company scientists say they have tried to reduce acrylamide levels by altering roasting times or steaming, but achieved only modest reductions and distorted the brew’s flavor and aroma.

Does Prop. 65 do a good job of protecting people from harmful chemicals?

Polsky and others who support the law point to Prop. 65’s successes: Coke and Pepsi removed 4-methylimidazole, a carcinogen in caramel coloring, from their sodas; companies have removed lead, a potent developmental toxin, from children’s jewelry, wine bottle caps and candy imported to the United States from Mexico. Target and CVS pharmacies have pledged to remove phthalates and formaldehyde from cosmetics and personal-care products due in part to pressure from the law.

But some worry that the sheer number of Prop. 65 warning signs seen in parking garages, auto mechanic shops, dentist’s and doctor’s offices and coffee shops erodes their clout. “Are you unduly frightening the public or are you posting warnings so often that people ignore them?” asks Eastmond. “Coffee and acrylamide might be one of those cases where we are warning someone about something that’s not really a serious health concern.”

Megan Schwarzman, an environmental health scientist and physician at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, agrees that the media spotlight on what looks like an absurd coffee warning could undermine the law’s effectiveness and overshadow cases where it has compelled large companies to remove or reduce truly dangerous chemicals.

And Schwarzman, Coughlin and Eastmond all point to one major failing of the law: It does not take into account the doses that were used in toxicology studies when deciding to list a chemical. People drinking coffee — even large amounts daily — do not come remotely close to the concentrations that caused harm in animal tests.

There hasn’t been a scientific evaluation of the law’s effectiveness to date. But Schwarzman, Polsky and a team of researchers are taking the first systematic look at whether Proposition 65 has been effective in one particular arena: reducing exposure of Californians to chemicals associated with breast cancer, such as endocrine disruptors, phthalate plasticizers and diesel exhaust.

Could Prop. 65 be improved?

Experts agree that there’s room for improvement in the way the statute is written and enforced.

One major criticism is that Prop. 65 warnings are too generic to be useful. Until now, signs usually have not noted which chemicals are present or whether people are at risk from, say, just walking to and from a parked car in a garage. Nor do they distinguish between high, medium and low risks. Warnings, Schwarzman says, should “only exist for significant public health risks.”

New rules taking effect in August will require inclusion of names of specific chemicals and their source.

Another criticism is that the law has become a cash cow for law firms seeking to force companies into settlements. In 2015, $26 million was paid in Prop. 65 settlements, of which nearly $18 million, or 68 percent, went toward plaintiff attorney fees. In 2016, the California attorney general’s office, which enforces Prop. 65, changed how settlements could be made in Prop. 65 lawsuits brought by private plaintiffs. The aim was to limit the portion of settlements that could go to plaintiffs and ensure that the state got its fair share of civil penalties. There still is no limit on how much of a settlement can go toward paying plaintiff attorney fees.

In another ongoing Prop. 65 court case, a judge ruled that the herbicide chemical glyphosate did not have to be labeled. Why not?

Glyphosate is a chemical found in the widely popular herbicide Roundup, produced by the company Monsanto.

Glyphosate, found in Roundup herbicide, was added to the Prop. 65 list in 2017. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified it as a “probable human carcinogen” but four other agencies have concluded it is safe. Roundup’s maker, Monsanto, has sued to avoid Prop. 65 warning requirements.

CREDIT: LEON WERDINGER / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Of the five triggering agencies, only the World Health Organization’s IARC has classified the chemical as a “probable human carcinogen.” The other four say it has low toxicity and does not pose a risk. Glyphosate went on the Prop. 65 list in July 2017.

The IARC is the most precautionary of the five triggering agencies, and works only with published data. In situations where much of the research is proprietary, that can be an issue, Eastmond says. He says he has seen the extensive unpublished data on glyphosate toxicology in rats, and epidemiology in exposed farm workers, and believes that the IARC very likely would not have reached the conclusion it did if it had reviewed those data too.

Monsanto does not want glyphosate regulated under Prop. 65 and sued the state of California in federal court in November 2017 to prevent a labeling requirement. A judge ruled in February that since only one agency had found glyphosate a possible carcinogen, the company could not be compelled to label its product as “known to cause cancer”; that would be compelled speech and could mislead a reasonable consumer. Glyphosate remains on the Prop. 65 list, but the judge temporarily barred the state from enforcing the warning requirement.

Neither the coffee nor the glyphosate case is settled. Some of the coffee companies may appeal after the final judgment of the penalty phase of that case is decided this summer or later, and the glyphosate ruling is just a “preliminary injunction” as that case proceeds.

What lawsuits might come next?

Prop. 65 lawsuits are scattershot and hard to predict, but there are clues. In the first week of May alone, private citizens filed 29 notices of violation with the California attorney general’s office seeking to sue companies for Prop. 65 violations. The complaints target items like phthalates in cosmetics, acrylamide in almonds and lead in dietary supplements. The notified companies include CVS pharmacies, Trader Joe’s and Nordstrom.

What might be listed next?

Processed meats — such as bacon and hot dogs — were listed in 2015 by the IARC as “carcinogenic to humans.” The agency listed red meat as “probably carcinogenic to humans” (the same category as acrylamide) because the evidence was more limited. Both listings, finalized in March, were based on epidemiological studies of colorectal cancer, which showed slightly increased risks associated with processed meat and red-meat consumption.

Coughlin suspects that this will trigger California to add processed meats to the Prop. 65 list. Interestingly, after facing public uproar in 2015, the WHO released a statement that processed meats were still part of a healthy diet.