Scientist John Harris doesn’t like to say the word “cure.” But after his discovery last year of a new strategy to alleviate a skin condition known as vitiligo, he now talks of a future in which long-term relief may be possible for the millions of people who have it.

Excited to share the results with non-scientists, Harris wrote about his findings in July 2018 for an online publication called The Conversation. He expected enthusiasm. Instead, he was blindsided by a wave of online hostility. “It was ‘F you. F you. You don’t even have vitiligo. What do you know?” recalls Harris, director of the Vitiligo Clinic and Research Center at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester.

The backlash stemmed from Harris’s choice of language: In his article, he had twice referred to vitiligo as “disfiguring,” once in the headline and again in the first sentence. Many people did not read past that word. “That just totally triggered people,” says Alicia Roufs, head of the Minnesota chapter of VITFriends, a national support group for those with vitiligo.

“I am losing my pigment. This does not classify as a disfigurement,” wrote one of the moderators of Vitiligo Pride, a Facebook group that counts around 6,000 members. If her dermatologist used such terms, she wrote in response to Harris’s article, she would tell the doctor to “stick it” and walk out.

In vitiligo, a faulty immune reaction kills off pigment cells called melanocytes and leaves patches of white skin. Considered an autoimmune disorder, vitiligo often emerges in adolescence or later, occurring in an estimated 1 percent of the world’s population and affecting all ethnic groups equally — although the depigmentation is more obvious on darker skin and carries greater social stigma in certain cultures. More than 50 separate gene changes have been linked to a greater risk of developing vitiligo, but what actually triggers it is unclear. (Some areas of the body, such as the face, are more likely to be affected, as are areas of the skin that have had trauma.)

In some small percentage of people, the patches clear up spontaneously, but most linger for life. That can take a psychological and emotional toll: Surveys show that the majority of people with vitiligo experience shame and insecurity; for some such feelings can bloom into clinical depression. And as with other kinds of immune activity gone awry, it can be hard on other parts of the body as well.

Studies suggest between 15 percent and 25 percent of those with vitiligo have at least one additional autoimmune disorder, including thyroid disease, inflammatory bowel disease and lupus. And because melanocytes also populate the inner ear, various tissues of the eyeball and even a layer of the brain’s protective coating, individuals with vitiligo can experience hearing loss, vision impairments and occasional neurological abnormalities.

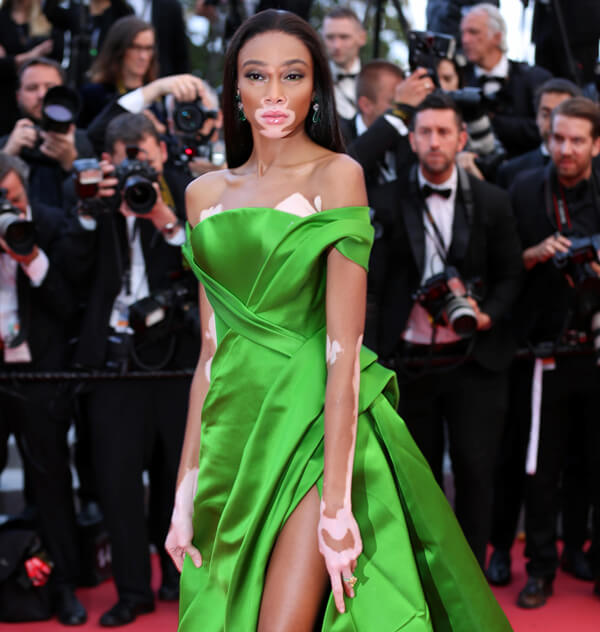

Yet because the changes wrought by vitiligo are mostly cosmetic, some in the vitiligo community have been working, with some success, to push back against defining it as a disease. In news reports, the face of vitiligo is Winnie Harlow, a supermodel who thrives with dappled skin. The online conversation is now dominated by social media influencers who promote messages of inclusivity and diversity on Instagram, Facebook and elsewhere. There, vitiligo is portrayed as beautiful, a skin-deep condition worth embracing, not fixing.

The public face of vitiligo: fashion model Winnie Harlow on the red carpet.

CREDIT: MICKAEL CHAVET / PROJECT DAYBREAK / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

But while Harris and other physicians say that they share the goal of decreasing the stigma associated with vitiligo, they have, just as this message of empowerment is going viral, found what could be antidotes. Based on a better understanding of how the immune system attacks pigment cells, they have devised a number of potential ways to stop it. Some remedies show promising results in mice; others are already being tested in people, with more on the way.

Scientifically, it’s an exciting time in vitiligo — even investors are beginning to see the promise. Last month, after securing funding from a British venture capital firm, Harris launched Villaris Therapeutics, the first fully-funded biotech startup to focus primarily on vitiligo drug development.

Which makes for strange days: Those who have committed their careers to studying and treating the autoimmune problem now find themselves caught between two competing narratives. To secure research money from funding agencies and to convince drug companies that vitiligo treatments are worth pursuing — even just to get insurance coverage for their patients’ medicines — they must emphasize the serious nature of the condition. But doing so risks alienating the very people they aim to help.

“It’s something we all have to navigate very carefully,” says Prashiela Manga, a pigment cell biologist at New York University.

A problem in the skin

Harris never set out to become a world-leading expert on vitiligo. His grandmother and great uncle had it, but he realized that only recently, and vitiligo was not on his radar in the late 1990s when he entered an MD-PhD program in Worcester, less than an hour’s drive from his hometown in rural Massachusetts.

Research dermatologist John Harris at the World Vitiligo Day Conference he hosted in 2018 in Worcester, Massachusetts.

CREDIT: MARK SKALNY PHOTOGRAPHY

A general interest in autoimmunity took Harris to a diabetes lab, where he focused on how the body trains its immune cells not to attack its own tissues, a problem in type 1 diabetes and all other autoimmune diseases. Harris didn’t want to specialize in diabetes, though. He was floundering for an academic direction when late one night he met a patient who would offer him professional clarity.

The young woman had landed in intensive care after simultaneously developing four new autoimmune disorder: diabetes, thyroiditis, pernicious anemia and vitiligo — a rare, but not entirely unheard of, occurrence. As Harris examined the woman, placing his stethoscope over a large milky-white patch of skin on her back, he thought to himself: “I can actually get the skin and study that.” He decided then and there to become a dermatologist, and to focus his research on vitiligo and devising new ways to correct the immune problems that robbed the skin of pigment.

Currently, the only FDA-approved drug for vitiligo — called monobenzone or Benoquin — actually worsens it, stripping the body of all remaining pigment cells to give the skin a more uniform tone. To restore skin color — which is to say, to treat vitiligo — the most effective therapy involves ultraviolet light. Zaps of UV radiation promote the regrowth of pigment-producing melanocytes and may help establish a healthier immune balance in the skin, as researchers describe in the 2019 Annual Review of Pathology. Doctors also commonly prescribe steroids and other drugs to further tamp down the immune assault and preserve melanocyte function.

None of these treatments is a cure-all, though. Light therapy, for example, demands frequent clinic visits over many months, and even then only a minority of patients experience marked improvements in skin color. Making matters worse for some are the complications beyond the skin — mental health struggles chief among them.“The psychosocial impact of vitiligo is profound, and it’s really not to be underestimated,” says Nada Elbuluk, director of the University of Southern California’s Skin of Color Center and Pigmentary Disorders Clinic.

When Harris began studying vitiligo in 2008, he looked for an existing animal model that might let him test new ways to counter the self-directed immune attack involved. There was a breed of chicken that lost its feather pigmentation, and a mouse with black fur that turned white. Yet despite having immune cells that targeted pigment-producing cells, neither animal showed signs of skin lightening, the hallmark of the condition in humans. So Harris set out to engineer an animal model that did.

Vitiligo supermodel

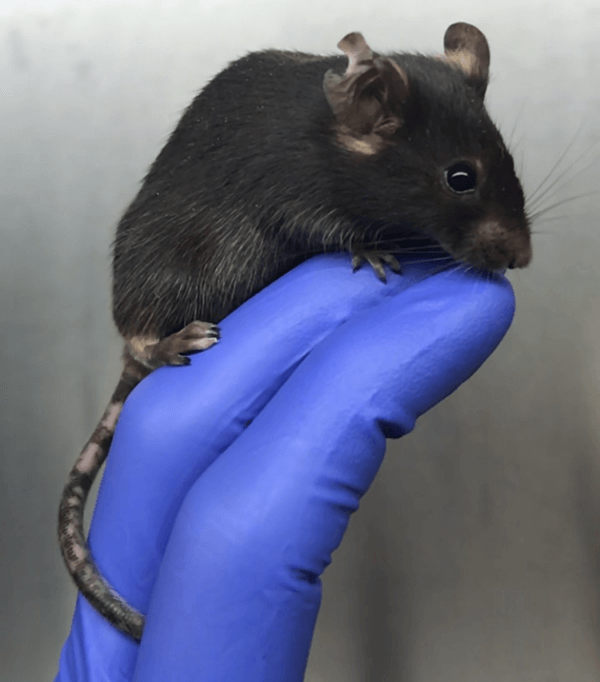

First, he needed a mouse with dark skin — the blackness of the “Black 6” strain typically used in lab studies only goes fur-deep. Harris found one: a colony of mice engineered to make melanocytes throughout their skin. He added a vitiligo-inducing immunity flaw into the mice, and white spots appeared on their ears, noses, feet and tails a month or so later.

Harris unveiled the new animal model in 2012. Using those mice, he managed to identify an immune-modulating drug that could protect pigment cells from an immune attack and prevent the skin from mottling.

Depigmentation is clearly visible on tail and ears of John Harris's mouse model of vitiligo.

CREDIT: VINCENT AZZOLINO / HARRIS LAB

While it’s still unclear what initially triggers vitiligo, scientists have made a lot of progress on understanding the molecular events that ultimately kill the pigment-producing cells. A large fraction of the genes linked to vitiligo are important in the immune system, notes Richard Spritz, a pediatrician and geneticist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora. It suggests that “vitiligo may be part of a normal immune surveillance in the skin … that’s gone wild a little bit.” And in people, it’s clear that a person’s own T cells, mistakenly targeting the self, spearhead the destruction.

Gearing up as if to deal with a foreign invader — or a tumor — the T cells produce an immune-stimulating molecule called interferon-gamma. Hearing the alarm, skin cells called keratinocytes amplify the call, instigating a biochemical cascade that attracts more misguided T cells to the skin. There, the immune cells besiege the melanocytes. Compounding the problem, the ranks of T cells produce even more interferon-gamma, resulting in a vicious cycle of destruction and depigmentation.

The drug Harris found could quell this pernicious feedback loop by inhibiting interferon-gamma. Stopping the T cells from flocking to the skin seemed to give pigment cells a chance to thrive again. But blocking interferon-gamma is not a good strategy for treating vitiligo — the body needs the immune molecule to fight infections. The only approved drug that targets interferon-gamma comes with severe side effects and is used to treat a rare, life-threatening blood disease. So Harris and his lab group looked for alternative drug targets.

Circulating T cells normally guard the skin against viruses, bacteria and other threats. But in someone with vitiligo the T cells destroy melanocytes. The attack involves a cycle of cellular destruction and depigmentation, in which the T cells release immune signaling molecules that activate certain skin cells. These skin cells signal for more T cells to arrive, and leads to more attacks on melanocytes. Drugs developed to treat rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases, called JAK inhibitors, can block this signaling to help promote melanocyte regrowth. But stopping the drugs can bring back the attack because of the presence of resident memory T cells in the skin, which are influenced by interleukin-15. One promising new strategy seeks to block IL-15 and kill the memory T cells.

They had some initial success, identifying two different immune signaling molecules that, when blocked, could prevent color loss and even restore pigmentation in mice. But the work didn’t persuade drug companies to invest in the approach. Instead, most industry research on vitiligo centers on repurposing a class of drugs already approved for treating a handful of autoimmune diseases.

Healing in the light

Known as JAK inhibitors, these agents block a different family of immune molecules, called the Janus kinase or JAK proteins, which also rev up the body’s T cell attacks on itself. These drugs arrived on the vitiligo scene after Brett King, a dermatologist at Yale University, published a case report in 2015 describing his off-label use of tofacitinib, a JAK-blocking agent from Pfizer. Although the drug was proven then to work only for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, King showed that it also helped to repigment the face, hands and arms of a middle-aged woman with widespread vitiligo.

King noticed, however, that the woman’s pigment wasn’t returning to skin concealed by her clothes. That prompted him to refer the patient to Harris, who took samples of her skin — applying gentle suction to create pus-filled blisters that he sucked dry with a syringe — so they could take a closer look. Together, the researchers showed that, on a molecular level, one needs light exposure, either natural sunlight or UV phototherapy, to produce a noticeable response to the drug.

To study the factors that influence vitiligo in people, John Harris takes suction blister biopsies from healthy and diseased skin.

CREDIT: JAMES STRASSNER AND MAGGI AHMED / HARRIS LAB

David Rosmarin, a dermatologist at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, independently came to much the same conclusion after one of his patients on a different JAK inhibitor, Incyte’s ruxolitinib, experienced repigmentation on all areas of his face except for the forehead, which was shielded from the sun by a baseball cap the man wore every day. “The treatment is really a two-part process,” Rosmarin says: It appears that the JAK inhibitor largely helps suppress the normal immune activation, and the light then stimulates the pigment cells to come back.

Since King’s initial report, many vitiligo specialists around the world have begun writing off-label prescriptions for tofacitinib or ruxolitinib — either in pill form, as manufactured, or as topical creams prepared by specialty compounding pharmacies. Although no large randomized studies are yet complete, other drug makers have also taken notice and started positioning their own experimental JAK-targeted agents as treatments for vitiligo as well.

“There’s a prevalence and a need in this space,” says Neal Walker, CEO of Aclaris Therapeutics, a dermatology-focused startup outside of Philadelphia with a JAK-blocking ointment now in clinical development for vitiligo. “Some of the most devastating conditions for patients are viewed as cosmetic,” he adds, and just because vitiligo is not life-threatening “doesn’t mean it’s not very important to the patient.”

Rosmarin is currently leading a trial, funded by Incyte, comparing ruxolitinib cream to a placebo ointment in more than 150 people with vitiligo. (Harris is a site investigator for both the Incyte and Aclaris trials.) In early testing, the topical treatment produced dramatic responses for some patients, especially on the face, with only minor side effects such as skin reddening and acne flare-ups. Trials to date have focused on adults, but given that half of all vitiligo patients are diagnosed before they turn 21, Rosmarin says he is optimistic that future trials will include children and teenagers.

Most vitiligo experts describe JAK inhibitors as the most promising new treatments in clinical testing for vitiligo. But they’re not a cure: “When you stop the drugs, the disease recurs rapidly,” notes Julien Seneschal, a dermatologist at the University of Bordeaux in France.

This tendency to relapse can be blamed on a unique type of skin-dwelling immune cell. After an infection by a virus or other pathogen, those cells — known as resident memory T cells — take root in the skin and operate as watchdogs, barking up a molecular storm (via interferon-gamma signaling) should they detect those pathogens again. Normally, this offers a frontline defense against future infections. In vitiligo, the cells misfire and flag melanocytes as intruders instead.

JAK inhibitors and other drugs can dampen the activity of those forget-me-not T cells, Seneschal says. “But they are not able to remove them.”

Recent research has pointed to a role for resident memory T cells in a variety of immune-related disorders, including vitiligo.

Forcing cells to forget

The importance of resident memory T cells in vitiligo emerged two years ago in reports from Seneschal’s team and an independent group led by Liv Eidsmo from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. But it was Harris and his colleagues who showed that the memory T cells were to blame for the persistence of vitiligo after stopping treatment. They also discovered a way to encourage the immune system to forget.

Reporting last year in Science Translational Medicine — and described in Harris’s piece for The Conversation — his team showed that the memory T cells found within skin patches of people with vitiligo had unusually high levels of a particular receptor, one that engages an important immune-signaling molecule called interleukin-15. In mice treated for two weeks with an antibody that blocked the receptor, and thus the interleukin-15 signals to the all-important T cells, the unwanted memory cells disappeared and there were lasting improvements in skin color.

“The tail and the ear repigmented very well,” says Jillian Richmond, an immunologist in Harris’s lab, “and the skin actually continued to improve because the melanocytes were regenerating and the memory T cells were not there to keep attacking.” The researchers euthanized the mice eight weeks after stopping treatment, but Richmond suspects that the benefit would have continued had they kept the animals alive longer.

Developed by JN Biosciences in California, the antibody therapy used in the mouse study has not been tested in humans, only monkeys. But another drug that blocks the same receptor (called CD122) has been, though not for vitiligo. The CD122 blocker was evaluated in small clinical trials as a potential remedy for a few different illnesses, including leukemia and celiac disease.

Through Villaris, Harris now hopes to license or discover a CD122 inhibitor and launch clinical trials for vitiligo within the next year or two. “We don’t have any treatments in dermatology that you can give for three months and the patients are better for years,” he says. “I think that could happen with this.” According to Villaris CEO Andrea Epperly, the company raised $18 million in its initial financing round — enough to fund the first-in-human safety studies and a follow-up trial to test for effectiveness.

An antibody drug that blocks the action of the immune signaling protein interleukin-15 (via the CD122 receptor) helped to dramatically repigment the tail of a mouse with vitiligo, compared with an untreated control, in experiments in John Harris’s lab.

CREDIT: JOHN HARRIS, CC BY-SA

Harris is clearly bullish on the prospects for a vitiligo therapy. Before founding Villaris, he also persuaded the NIH to fund a vitiligo trial, expected to launch later this year, that will test an antibody drug targeting the interleukin-15 signaling molecule itself, rather than the receptor. (Harris later recused himself from participating because of competing commercial interests.) Others are uncertain if the story is that simple and are waiting to see if Harris’s findings can be validated in patients.

“The potential is there for long-term remission,” says Iltefat Hamzavi, a dermatologist at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. But targeting memory T cells might not be enough. “This assumes that everything is immune-based,” he says, “and there may be some melanocyte defects that also cause the problem.”

There also could be unintended consequences of wiping out this vigilant immune population from the skin, notes Mary Jo Turk, a tumor immunologist at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine in New Hampshire. In mice with vitiligo, Turk showed that memory T cells are critical in fending off melanoma. A team from Australia reported earlier this year that mice lacking these cells in the skin were more susceptible to developing cancer. “There’s always a fine line between treating autoimmunity and releasing control against cancer,” Turk says.

Only clinical trials will show whether these new approaches work safely in patients. Such trials are expensive, though — and despite Harris’s promising mouse data, many would-be financial backers had trouble seeing past the social media discussions about acceptance and empowerment. It was only after numerous rejections, Harris says, that he found a funder that recognized the medical need and market opportunity for a vitiligo treatment.

Tale of two narratives

The strength of the fight against stigma in the vitiligo community was well illustrated by the swift — and overwhelmingly negative — reaction that Harris received in 2018. And it didn’t help that his story landed a week after Aerie, a lingerie brand, launched a marketing campaign featuring young women that news reports described as having “visible disabilities” and “chronic illnesses.”

Alongside a wheelchair user, a Paralympian with Down syndrome, a bald cancer survivor, a woman wearing an insulin pump and another with an ostomy pouch — all in their skivvies — was an aspiring model with vitiligo, the white spots on her chest, arms and face clearly visible against her darker natural skin tone. The insinuation in some readers’ minds: Vitiligo is just another disabling disease.

“That’s the kind of thing that pisses me off,” Jasmine Abena Colgan, a contemporary artist with vitiligo whose work focuses on labor and pigmentation, told Knowable. “Calling us diseased and ill and sick, it’s really close-minded,” she says. “It’s not a disease. I can’t stress that enough.”

If that outlook works for Colgan, all the power to her, say Harris and others. But some worry that the strong voices of people like Colgan may drown out the whispers of those who are suffering — desperately self-conscious teenagers, say, who avoid wearing shorts so that no one will ask about the white spots on their knees. And “if patients are not seen asking for better treatments, then it’s hard to justify to companies that this is going to be a worthwhile investment,” says Vaneeta Sheth, a dermatologist at the Lahey Hospital and Medical Center outside Boston.

That concern, already widely shared across the medical community, is beginning to ripple out to some vitiligo-focused forums such as Living Dappled, a prominent vitiligo blog. “We have these two conflicting narratives, and it’s alarming to me to see the one outweighing the other,” says Erika Page, editor in chief of the site. “The acceptance one is the one that’s splashy and all over the media, but that doesn’t make that the truth. There is still another truth, and we need to balance the narrative.”

For Harris, the effect of the movement became evident during a conversation last year with a representative of a major pharmaceutical firm. The company was just months away from launching a large and expensive drug trial for vitiligo and, as Harris tells it, “he came up and said, ‘It seems like people don’t mind their vitiligo. They actually like it, John. Do we really need to spend time creating a drug for this?’” (Harris managed to convince the man otherwise, and the company’s trial went ahead late last year.)

“It’s an interesting time that we’re in,” muses Victor Huang, a vitiligo specialist at the University of California, Davis. “At the same time as we are better understanding the impact on people’s lives — and we’re able to measure rates of suicide, depression, mood disorders, developmental issues as well as other autoimmune conditions that go along with vitiligo and would strongly argue for this being a medical condition — there is also a cultural shift that is happening.” People are embracing their appearance, vitiligo and all.

“It is a tightrope to walk,” Huang says. “But both perspectives are valid and necessary.”