Public health activities stretch way back to antiquity, when people began living in larger groups and their garbage and waste attracted disease-spreading rodents and insects. Later, when the bubonic plague spread across Europe in the 14th century, the practice of quarantine emerged to protect coastal cities. Ships sailing from infected ports were made to sit at anchor for 40 days before docking in places like Venice and Milan.

Here are key moments that led to the US public health system as we know it today.

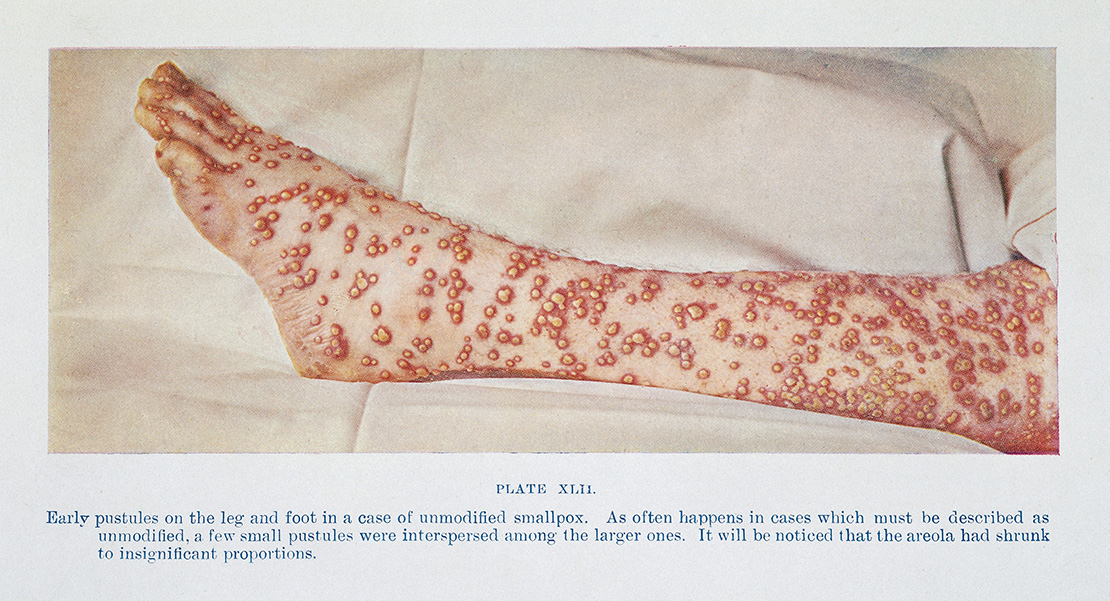

CREDIT: WELLCOME COLLECTION

1701: Massachusetts mandated isolation of smallpox patients. Permanent councils were established to enforce quarantine and isolation rules in Philadelphia, New York and other cities by the end of the 18th century.

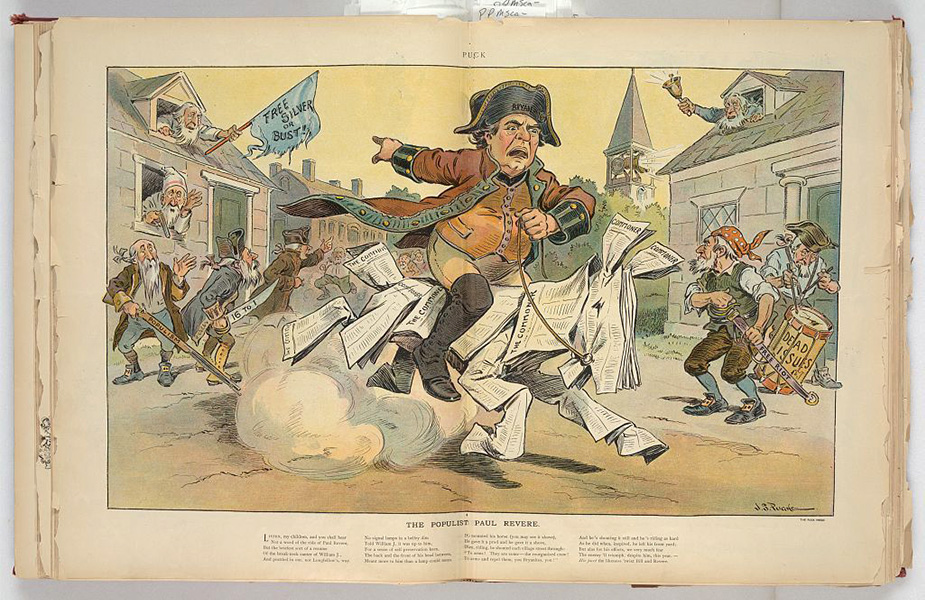

CREDIT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

1799: Boston established the nation’s first board of health and health department to address a potential cholera outbreak. Paul Revere was the first health officer.

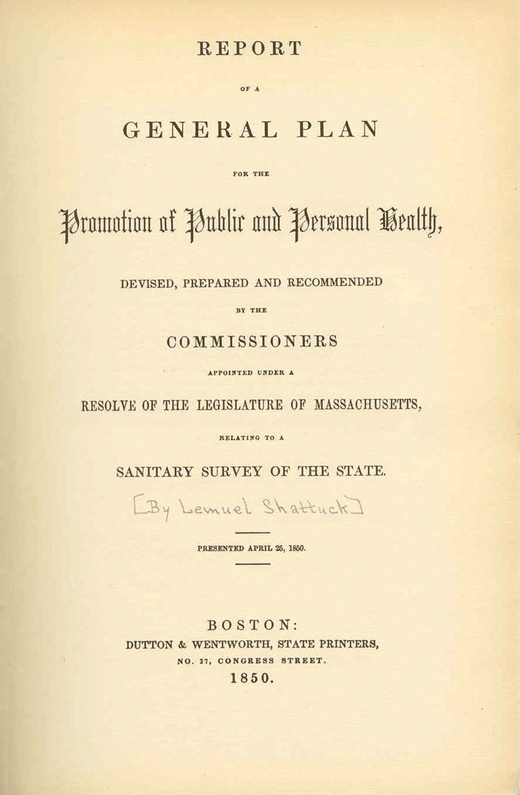

CREDIT: PUBLIC DOMAIN

1850: Lemuel Shattuck, a Massachusetts bookseller and statistician, published a Report of the Massachusetts Sanitary Commission, documenting death and illness rates around the state. He concluded that citizens who tried to maintain “clean and decent homes” caught diseases due to the behavior of others. His report was “one of the most farsighted and influential documents in the history of the American public health system,” a 1988 Institute of Medicine report said.

1872: The American Public Health Association was established, marking the professionalization of the emerging field. One of its first actions: a public health survey, sent to every town with more than 5,000 residents, to gather information about the water supply, sewer systems and other community health topics.

1899–1900: When a plague outbreak hit Honolulu, health officials used a “cordon sanitaire,” roping off 14 blocks of the city and isolating 10,000 people.

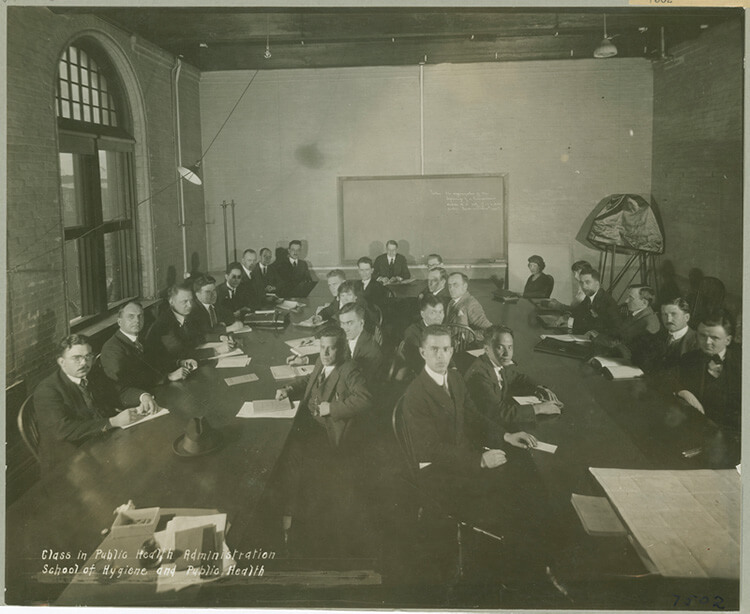

CREDIT: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

1910: The federal Public Health Service started investigating poor working conditions and their effect on workers’ health. Among other things, it revealed unsanitary conditions and high rates of tuberculosis in the garment-making industry.

CREDIT: PUBLISHERS PHOTO SERVICE / LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

1912: When malaria eradication became important, Public Health Service workers used drip cans containing oil and kerosene to eliminate mosquito-breeding areas.

CREDIT: COURTESY OF THE ROCKEFELLER ARCHIVE CENTER