The most common strategy for a vaccination campaign is simple: “If we build it, they will come.” But what if millions of Americans won’t get vaccinated for Covid-19? A growing number of experts say that public health agencies have it backward. The strategy should be: “If we build it, we must take it to the people.”

In a January 2021 survey of Americans, more than 4 in 10 Black adults, about the same proportion of all young people (age 18 to 29), and nearly as many Hispanic adults said they would be hesitant about getting an FDA-approved vaccine when it is available. They would “wait and see” how a vaccine worked for other people. In the same survey, by the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation’s Covid-19 Vaccine Monitor, a third of Republicans said they definitely would not get an inoculation, or would get one only if required for work or school.

And that presents a problem: A high proportion of the US population — estimates range from 70 to 90 percent — must be vaccinated for Covid-19, or have gained antibodies following infection, for the country to achieve “herd immunity,” allowing life to return to more or less normal. Vaccine hesitancy could threaten chances of reaching that target.

The problem isn’t going away soon. Dangerous Covid-19 variants have emerged in the UK, South Africa and Brazil and have already reached the United States; these seem to spread more easily and quickly than the original. Other threatening variants could emerge — and populations that resist vaccinations not only will see high ongoing infection rates but will also present ripe breeding grounds for such hardier or more infectious strains, even if herd immunity is reached in many areas. And since Covid-19 might return seasonally, like influenza, new or more frequent vaccinations and boosters could be needed.

For all these reasons, social and behavioral scientists are calling on governments to change what they do on the ground to improve vaccination rates. They are pointing to lessons learned from rural West Africa, to villages in India, to urban neighborhoods of the US Midwest, where public health authorities are cultivating long-term, in-person relationships with local leaders and residents. A familiar face can go a long way to reducing vaccine hesitancy.

“Health officials need to listen to individuals and community organizations, providing local people with opportunities to be heard and have their concerns acted upon,” says Emily Brunson, a medical anthropologist at Texas State University. She and others call for “human-centered” public health interventions instead of today’s more common top-down strategies.

Survey data from the Pew Research Center show how people’s feelings about a Covid-19 vaccine have shifted over time in the US. Acceptance rates have climbed after dropping after May 2020, but a significant percentage of people still say they will probably or definitely not get a vaccine.

Vaccination campaigns, for instance, should give communities a greater voice in vaccine rollouts, including the locations where inoculations will be provided, Brunson says; making a vaccine difficult or uncomfortable to get only fuels reluctance. To reach some hesitant populations, Covid-19 vaccines could be delivered at houses of worship, barbershops and schools in addition to hospitals and public health centers. Vaccines should be as accessible as possible — which in some cases involves more factors than just location. Immigrants or undocumented persons, for example, could be wary of any vaccination site that is security focused, checking IDs, and this could prevent them from going there.

“It’s important to figure out who are the most marginalized people living in your area,” Brunson says. “How can you make the vaccine easy for them to get? That is what vaccine equity looks like.”

Influencers versus misinformation

The reasons for hesitancy differ from community to community and even within neighborhoods. Black Americans, for example, can have different reasons to be hesitant than recent-immigrant neighbors: Many face not just disparities in health and medical treatment, but also a history of medical neglect or abuse, including the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study and surgical experiments on enslaved women. “Among the Black community, concerns about human testing make trust in government right now very tenuous,” Brunson says.

In the United States and the United Kingdom, antivaccine misinformation has raced through certain groups, be they progressive wellness communities on social media or tightly knit traditional societies, including Somali immigrants, Orthodox Jews and the Amish. Many have been receptive to the spurious claim by disgraced former physician Andrew Wakefield that the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine increased the risk of autism. Although MMR vaccination rates have remained high overall for the US during the past decade, clusters of hesitancy continue, making certain communities vulnerable, according to a 2019 overview in the Annual Review of Virology.

By 2017, for example, the vaccination rate for two-year-olds in Minnesota’s 52,000-strong Somali community during the previous 10 years had dropped from one of highest in Hennepin County, which includes the city of Minneapolis, to one of the lowest. That year, a severe measles outbreak afflicted the community. Reaching its members by traditional means wasn’t going to work, says Patsy Stinchfield, an infectious-disease nurse practitioner and senior director of infection prevention and control with Children’s Minnesota, the largest pediatric hospital system in the region. “In an infectious disease outbreak, you’d typically use the news media, social media, posters in the clinic waiting rooms, and flyers to reach the entire population,” she says. “But none of those methods is effective for the Somali community, which relies on oral communication to deliver messages. Their most trusted people are religious leaders, the imams.”

So Stinchfield set out to change minds among the community’s influential oral messengers. She organized outreach panels for imams at mosques in the Twin Cities to explain how vaccine misinformation reduced local Somali inoculation rates, driving the measles epidemic. The most effective panels, she says, included not only herself as an expert from a large pediatric health system but also local Somali public health workers and clinicians.

The imams were almost universally receptive. “They talked among themselves, saying, ‘We have to go back and tell people what the science is and how to protect our children,’” Stinchfield says. “After we did a number of panels, the imams said, ‘We’ve got this now.’ You can think of it as a train-the-trainers model.”

The effort worked — to a point. Immunization rates for Somali two-year-old children increased from 42 percent from an April 2017 outbreak to 60 percent in August 2017. But Stinchfield says that in subsequent years inoculation rates fell again, a trend exacerbated by the Covid pandemic. And though rates are slowly climbing back, they are still far below the 95 percent level needed for community immunity for measles. “We are still working on hesitancy as we approach Somali families around Covid vaccines,” Stinchfield says.

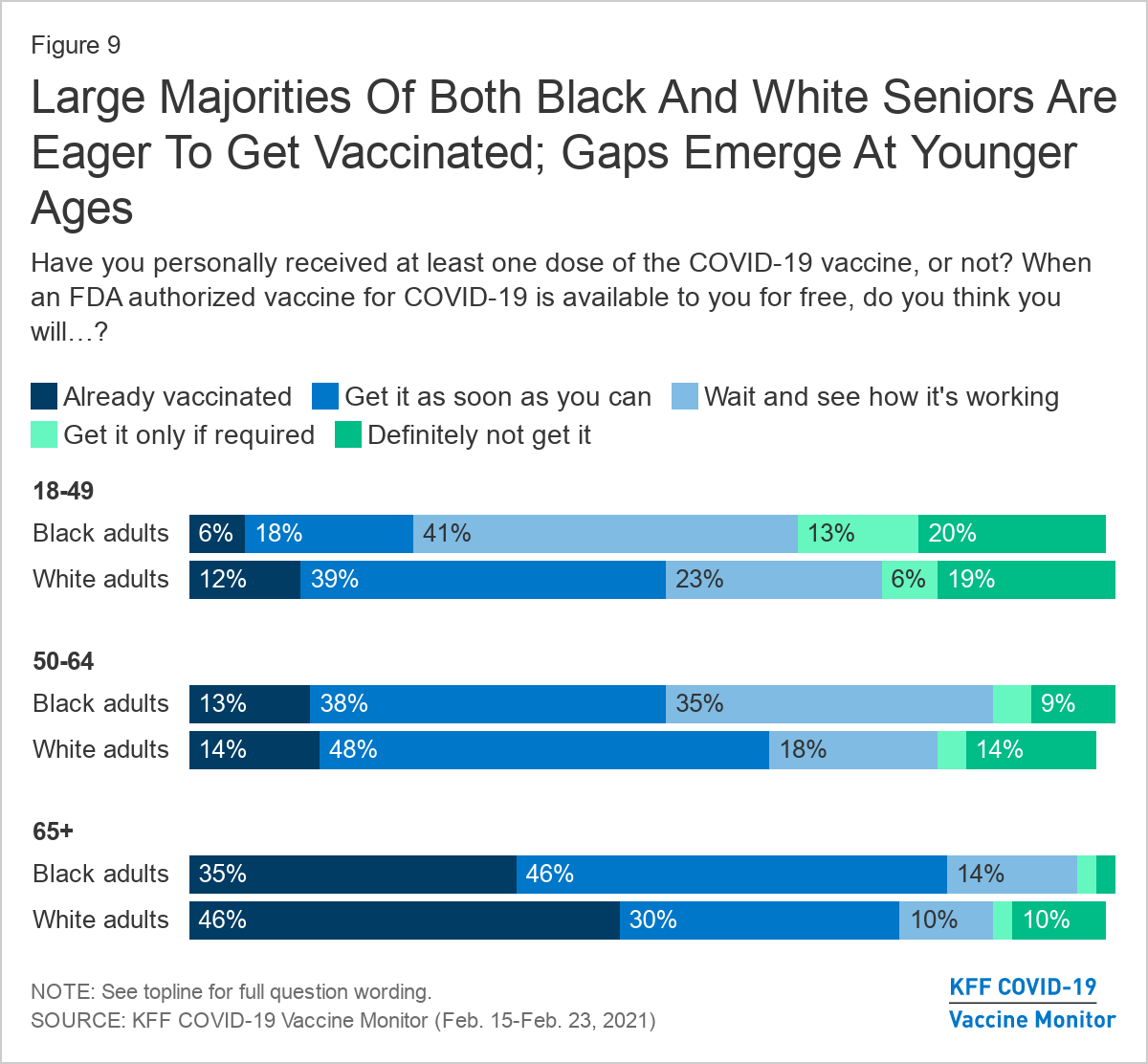

Rates of US vaccine acceptance differ between Blacks and whites and by age, as illustrated in this February 2021 survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Lessons from polio and Ebola

Other examples of successful public health campaigns hold lessons for today. In 2009, more than half of the global cases of poliomyelitis were in India, but after a public campaign filled with trusted community members who could open doors closed to others, the country was certified polio-free in 2014. The Social Mobilization Network (SMNet) established in the polio endemic states of Uttar Pradesh in 2002 and Bihar in 2005 harnessed local religious leaders, community influencers, counselors, mothers’ meetings and rallies to convert resistant families into vaccination advocates. SMNet trained more than 7,300 of these “social mobilizers,” 98 percent of them female. It also deployed mass media messages and print materials to buttress the effort.

Another notable example of social mobilization occurred during the 2014-16 Ebola epidemic in West Africa. Governments and international aid agencies initially emphasized Ebola’s deadliness in their messaging. Frightened people hid from authorities and avoided seeking medical care. Many were angry that they were not allowed to bury their dead in traditional ways. “The public health experts came in with a disease-centered approach to the response and not a human-centered approach,” says Sharon Abramowitz, a medical anthropologist with UNICEF. “They wasted months chasing microbes in people rather than working with people to prevent the spread of microbes.”

Anthropologists and other social scientists argued that West African communities would be more likely to cooperate with authorities if they were listened to and engaged with respect, Abramowitz related in a 2017 article in the Annual Review of Anthropology. Eventually, aid organizations and governments reversed course and coordinated thousands of volunteers, employees and Ebola survivors as social mobilizers to help develop local, community-driven epidemic action plans.

In the Kono District in Eastern Sierra Leone, for example, 14 chiefdoms developed Ebola task forces to advise local people on safe funeral practices and coordinate infection-control efforts with aid organizations. More than 300 local contact tracers and supervisors were hired and trained to identify and track cases.

Convincing the community

Social and behavioral scientists have identified various messaging tactics that should be borne in mind when crafting effective campaigns. “Most of the messages hinge not only on protecting yourself but also helping other people,” says Jay Van Bavel, a social neuroscientist at New York University who cowrote an April 2020 Nature Human Behavior article on how to apply behavioral science to the Covid pandemic.

A standard public health statement aimed at everyone won’t cut it, Van Bavel says. Instead, you have to think about what motivates a certain population and target a message focusing on that. A message for young people might emphasize protecting vulnerable parents and grandparents, for example. A message for devout audiences could be delivered by clergy, emphasizing religious or moral norms.

Friends, family, neighbors and even acquaintances who face similar experiences or problems can be among the strongest vaccine influencers. “For new parents trying to determine the credibility and safety of vaccines, the opinions of other parents are often seen as more relevant than the opinions of expert epidemiologists,” writes Damon Centola, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania, in his 2021 book Change: How to Make Big Things Happen.

If you hope to change someone’s mind, bring plenty of backup. As Centola writes, “People need to receive reinforcement (or ‘social proof’) from multiple adopters to be convinced — and for the new behavior to propagate.”

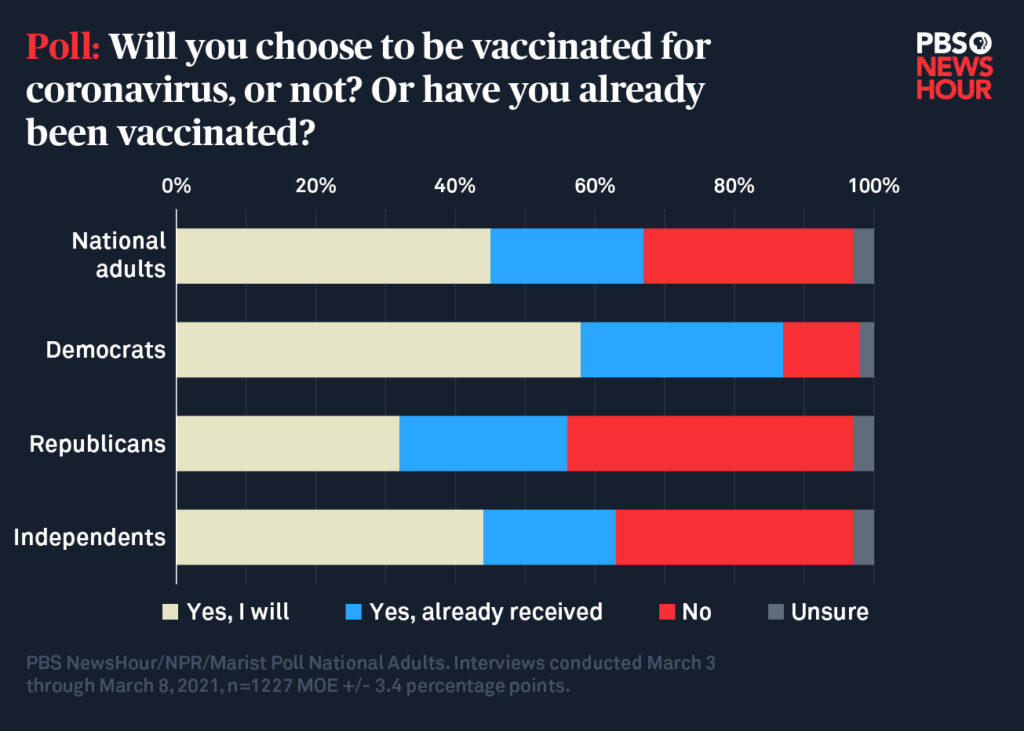

Vaccine acceptance rates differ starkly along political lines, according to this March 2021 PBS NewsHour/NPR/Marist poll.

What about eradicating all the misinformation that’s spreading virally online? Vaccination campaigns have always been challenged by false rumors and fantasies of harm, notes Heidi J. Larson, an anthropologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and author of a 2020 book, Stuck: How Vaccine Rumors Start — and Why They Don’t Go Away. Especially in these days of viral social media, quashing all the rumors and conspiracy theories is a tall order, she holds. In any case, she says, “the bigger issue is the underlying distrust, the feeling of being disenfranchised and not heard.”

And that takes community engagement. Here, says Abramowitz, some low- and moderate-income countries might eventually do it better than richer nations because they have built local outreach into their health programs. The Sindh province of Pakistan, for example, crushed its 2020 Covid outbreak by reaching out to communities with informational campaigns and sanitation measures.

When people are faced with difficult choices that involve risk, they want direct, face-to-face discussions with health experts, according to Abramowitz. People need more detailed, accurate and precise information in times of uncertainty, not less, and community engagement at a person-to-person level is the best way to provide that. But the United States has been reluctant to invest in its frontline public health workforce.

Some local health programs are starting to turn that around, forging partnerships with clergy and other leaders of vulnerable groups that have been less likely to receive vaccinations because of both hesitancy and lack of access.

Surveys also find that vaccine hesitancy is especially strong among younger Republicans and conservatives, another obstacle to reaching herd immunity. Pollsters are working to understand what messaging would help to change their minds. In recently reported results of a small focus group of vaccine-hesitant Republicans, participants said they were unpersuaded by appeals from politicians and instead were swayed far more by nonpartisan vaccine facts and personal stories.

There are reasons to hope that Covid vaccine hesitancy will erode to some extent as time goes on. Already, 69 percent of the public has received a vaccine or intends to get one. That’s up from November, when 60 percent said they planned to get vaccinated. Right now, chronically underfunded local health agencies are sharply focused on administering vaccines as quickly as they can. But researchers hope that when local officials have more capacity, they will turn to tackle hesitancy and might visit personally and repeatedly with community leaders and other influencers to encourage acceptance, as was done for measles vaccinations in the Minnesota Somali community.

And as more people get vaccinated, more and more people will know people who’ve gotten their shots. That will help — because if you know someone who has been vaccinated, you’re more likely to get a shot yourself, the January Kaiser Family Foundation survey found.

Covid could be with us for many years, and we need to be prepared for future pandemics and sporadic outbreaks of familiar infectious diseases. For that inevitability, Stinchfield says, public health authorities should prepare by building longer-term trust among local people. “Clinics should be driven by and for the community that they’re serving,” she says. “We should not expect people to travel long distances to come to big metro medical centers. We need to bring more of those services out to where people live and work.

“And we need to listen first, asking, ‘What is it that you need? Is it a school-based clinic, services to your pharmacy in your town, or having a nurse practitioner that makes house calls?’ We need to be more creative than having one model of expecting everybody to come to us.”

This article is part of Reset: The Science of Crisis & Recovery, an ongoing Knowable Magazine series exploring how the world is navigating the coronavirus pandemic, its consequences and the way forward. Reset is supported by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.