A devastating nerve disease stalks a mountain village

Neurologists have grappled with a cluster of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cases in France, where a fondness for a toxic wild mushroom may hold the answer

Support sound science and smart stories

Help us make scientific knowledge accessible to all

Donate today

The road switches back and forth again and again as it climbs into Montchavin, perched in the French Alps at 4,100 feet above sea level. The once-sleepy mountainside village, developed into a ski resort in the 1970s, is dotted with wooden chalet-style condo buildings and situated in the midst of a vast downhill complex known as Paradiski, one of the world’s largest.

Well known to skiers and alpinistes, Montchavin also has grabbed the attention of medical researchers as the site of a highly unusual cluster of a devastating neurological disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

ALS, brought about by the progressive loss of nerve function in the brain, spinal cord and motor neurons in the limbs and chest, leading to paralysis and death, is both rare and rather evenly distributed across the globe: It afflicts two to three new people out of 100,000 per year. Though Montchavin is flooded with visitors in winter and summer, the year-round resident population is only a couple hundred, and neighboring villages aren’t much bigger, so the odds are strongly against finding more than just a few ALS patients in the immediate area. Yet physicians have reported 14.

In the countryside around Montchavin, false morel mushrooms emerge in the springtime. Locals involved in the ALS cluster would seek them out for their flavor and supposed rejuvenating properties.

CREDIT: HENK MONSTER / WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The first of the village patients to arouse suspicion in Emmeline Lagrange, the neurologist who has led the investigation into the problem, was a woman in her late thirties, a ski instructor and ski lift ticket-checker originally from Poland who worked in the offseason at the local tourism office. It was 2009. A physician in Montchavin had referred the woman to Lagrange, who practices at Grenoble University Hospital, 84 miles southwest of the village. Lagrange diagnosed ALS and recalls phoning the Montchavin physician to explain the consequences: “The first thing she said was, ‘I certainly know what it is. It’s the fourth case in the village. My neighbor died of ALS 20 years ago and two friends of hers are still victims of the disease.’”

Lagrange didn’t expect to find other ALS cases in the vicinity. But a newspaper story about efforts to raise money for a man who needed a wheelchair led her to one patient. A pharmacist helped her to find another. Lagrange recalls being “very afraid” as the cases added up: another in 2009, three in 2010, two in 2012, one each in 2013, 2014, 2015, the last in 2019. Ultimately, she identified 16 ALS cases, though only nine men and five women agreed to be further studied. Lagrange herself examined 13 of them. Their age at diagnosis ranged from 39 to 75.

Most had spent at least a decade in Montchavin, some their entire lives. Most were French natives, but they also hailed from Poland, Turkey, Canada and the United Kingdom. There was a married couple — he was a ski instructor and an offseason lumberjack, a Montchavin native, and was diagnosed in 2005 at age 63; she worked in a restaurant and was diagnosed eight years later at age 67. In keeping with the mountain lifestyle, all but one had been very physically active. Some were year-round residents, others were seasonal.

A remarkable thing about ALS is the mystery surrounding the underlying cause or causes of most cases. To some extent, the disease runs in families, making up as much as 10 to 15 percent of the toll, and scientists have pinpointed numerous genes that drive these familial cases. Beyond those, medical researchers have variously found that exposure to cigarette smoke, air pollution and some industrial chemicals is associated with an increased risk of ALS. And US military veterans also have a 50 percent higher risk of ALS than nonveterans. Still, no definitive cause and effect has been established.

None of the Montchavin patients, Lagrange learned, had a family history of ALS, and of the 12 whose blood was tested, none was positive for an ALS susceptibility gene. So she and her colleagues turned to the environment. They tested drinking water and garden soil for toxic substances. They considered a compound that ski resorts add to the water that’s blasted out of the snowmaking machines. They tested for lead, given the presence of a long-closed lead mine in the vicinity. They measured household levels of radon, a radioactive gas emanating from soil and stone. Clues surfaced here and there, but the researchers hadn’t discovered any single, obvious risk factor that all the patients had in common.

A remarkable thing about ALS is the mystery surrounding the underlying cause or causes of most cases.

In 2017, Lagrange and five colleagues summarized their findings in an abstract, “A high-incidence cluster of ALS in the French Alps: common environment and multiple exposures,” making clear that, after eight years, there was no real answer. “Patients are neighbours and share many exposures, some of them being known for their toxicity.… Other factors are more exploratory,” the scientists wrote. Meanwhile, officials with the French health agency released their own analysis, saying they had found no evidence of a common risk factor and that the ALS cluster was “probably linked to the random distribution of cases.”

Looking back, Lagrange says in an interview, “We were at a stop. We had no more ideas.”

Yet the abstract contained one phrase that would prove pivotal: Six of the patients, it said, “used to eat local mushrooms.”

An island of suspect seeds

The notion that something in food might cause ALS does not come out of the blue. It comes from Guam, where US medical researchers, near the end of World War II, documented an epidemic of neurological disease among the island’s native Chamorro people that has by now largely disappeared. At its peak, the epidemic was so severe, with a prevalence more than 100 times the norm, and so complex, incorporating a second neurological disorder known as parkinsonism-dementia, that the National Institutes of Health opened a research station on the island to study the disease, known as Western Pacific ALS-PDC.

A long series of researchers has proposed different causal explanations for ALS-PDC, from aluminum in the soil, to viruses, to genetics, to abnormal, misfolded proteins called prions. Debate still flares up. But perhaps the most widely received theory centers on the seeds of cycad trees that once grew wild on the island in abundance. Historically, Chamorro people consumed the plum-sized, starchy seeds or incorporated them into medicines. Because they are poisonous, a traditional cooking technique was to soak chopped seeds in multiple changes of water before grinding the material into paste or flour. Still, the processing protocol did not necessarily remove all the toxins, and therein lies the danger.

The leading proponent of the cycad hypothesis — that exposure to cycad seed toxins can eventually lead to ALS-PDC — is the environmental neuroscientist Peter Spencer of the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. For nearly four decades, he and his coworkers have pursued the question in the field, the clinic and the laboratory. Today, they view the origin of Western Pacific ALS-PDC as a train of events similar to that of chemical carcinogenesis, with a key difference: Instead of a chemical insult altering the DNA of a dividing cell and initiating the growth of a tumor, it alters the DNA of a nerve cell, which is nondividing, and kills it.

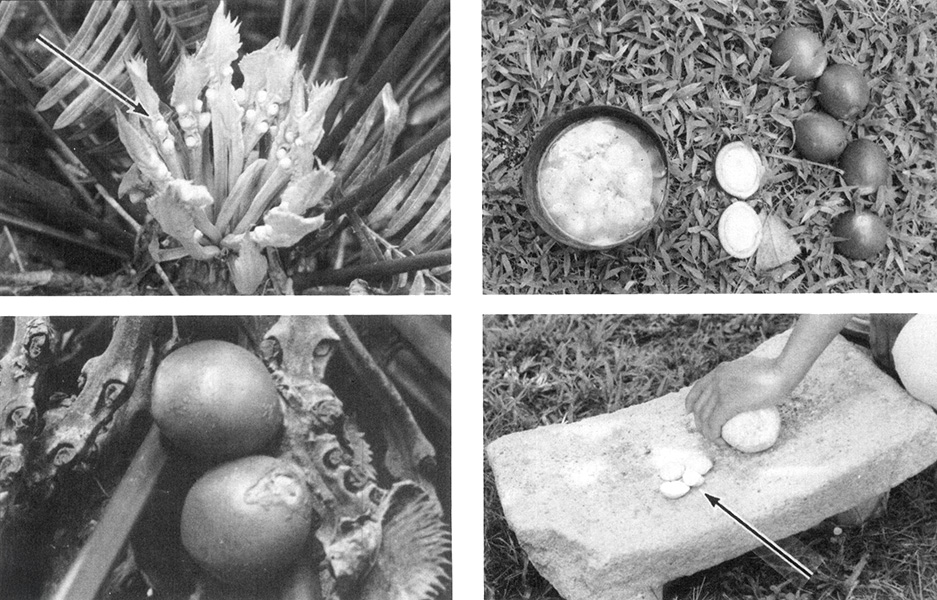

Cycad seeds contain toxins; these were linked to an outbreak of cases of ALS on the island of Guam after World War II. In this image, top left shows the Immature seeds of Cycas circinalis; lower left shows mature seeds; upper right shows a seed split open and its starchy center being soaked in water to remove toxic chemicals. Finally, lower right shows the traditional method for grinding the treated and dried material to make flour for food. Problems arise when the treatment is inadequate and toxins remain in the flour.

CREDIT: P.S. SPENCER / THE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGICAL SCIENCES 1987

Spencer and colleagues focus in particular on a compound in cycad seed called cycasin. In the body, an enzyme converts cycasin into methylazoxymethanol, or MAM, a highly reactive substance that also happens to be formed when the body metabolizes hydrazine, a volatile chemical used in rocket fuels and industrial applications. Experiments show that MAM can alter DNA (by attaching damaging, reactive methyl groups to the DNA component guanine). Though the body is also equipped with an enzyme capable of repairing the damage, “the adult human brain often has very low levels of this critically important DNA-repair enzyme,” Spencer wrote in the journal Frontiers in Neurology in 2019, in an article laying out his latest thinking about Western Pacific ALS-PDC. “DNA damage accrues and activates cell signal pathways associated with human neurodegeneration.”

Any neurologist grappling with a surprisingly large number of ALS cases in a small area during a defined period is likely to think about the cases in Guam. So Lagrange was excited for her research partner, the neurologist William Camu, to meet Spencer at a 2017 conference in Strasbourg, France. She was not disappointed.

Spencer, for his part, remembers the summary prepared by Lagrange and Camu (published as an abstract), which Camu presented at the meeting. “I noted that among the foodstuffs they reported were mushrooms,” Spencer recalls. “And I asked them what type of mushrooms, because one particular type contains poisons associated with the Guam problem.”

Lagrange, at this point collaborating with Spencer and his close colleague and spouse Valerie Palmer, a neurology researcher also affiliated with Oregon Health & Science University, renewed the investigation in the Alps, meeting some patients and their loved ones and asking questions. And she found that all of the patients had eaten false morels, which emerge in spring in forests in Europe, North America and Asia. False morels are so poisonous it is illegal to sell them in France.

Lagrange and coworkers learned that the ALS patients had deliberately sought out false morels for their supposed “rejuvenating” properties as well as their flavor. Indeed, the ALS patients knew one another and actively shared information about where to find the fungi. “They are always in a group, a secret group, a social network, and they eat the mushrooms,” a village elder explained to Lagrange. “And they all knew that it’s forbidden.”

Significantly, half of the French ALS patients had previously become acutely ill after consuming what they described as morels.

A true morel Morchella esculenta (left) and false morel Gyromitra esculenta (right). The mushrooms superficially resemble each other, which might lead to confusion by foragers. However, some people deliberately harvest G. esculenta and treat it before consumption to try to remove the toxins it contains.

CREDIT: LEFT: KATHINKADALSEG, RIGHT: NINA FILIPPOVA / iNATURALIST

To show that the consumption of false morels and the development of ALS in this group was more than a mere coincidence, the researchers broadened their study to include a control group: 48 people from the same area who were roughly the same ages. Control subjects also ate wild mushrooms — but not false morels. There are plenty of species of false morel, but the best known and most poisonous is Gyromitra esculenta, one of the types collected and consumed by patients in the Montchavin ALS cluster.

“Since no other significant chemical or physical exposure was found,” Lagrange et al wrote in a 2021 paper in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences, “the primary risk factor for ALS in this community appears to be repeated ingestion of these neurotoxic fungi.... Indeed, this is the discriminating element between ALS-affected and control inhabitants.”

Some researchers are skeptical. Jeffrey D. Rothstein, a clinician and neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine specializing in ALS, says he is not convinced that the cases in the French Alps have a shared cause; rather, the grouping may just be coincidence. “There’s always that chance event that things can happen,” he says, and notes that other ALS clusters have been reported in the past that later turned out to be random. Though he does support the cycad hypothesis, he says he has little confidence in most theories positing that dietary or environmental chemicals trigger ALS. He tends to believe that even sporadic ALS, in the end, will turn out to be a largely genetic problem.

Still, his mind isn’t totally closed to the cluster in France. “Could there be something here? Sure. But somebody needs to do more than this sort of loose association study to prove it.”

Others are more convinced of the study’s importance. Evelyn Talbott, an environmental epidemiologist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, who coauthored the chapter on ALS epidemiology in the 2016 Handbook of Clinical Neurology, says she thinks the study was “strong.” She was struck, she adds, by the case of the husband and wife who both ate false morels and developed ALS. So-called conjugal ALS cases are exceptionally rare. The study’s conclusion “raises a red flag,” she adds, and wonders why the World Health Organization hadn’t issued a warning about consuming false morels.

Carmel Armon, a neurologist at Loma Linda University in California and an expert on ALS epidemiology, says the French cluster is “well researched and credible.” And the underlying pathogenic explanation, he says, “makes perfect sense to me.”

That explanation, laid out by Lagrange, Spencer and coworkers in several papers, goes like this: Gyromitra esculenta, whose very name hints at humans’ curious fondness for it — esculenta means “edible” — has long been known to cause sickness and even death. Traditionally, foragers boiled or dried the fungi to remove the toxins before eating. In 1968, scientists isolated the main toxin and called it gyromitrin. The chemical has been extensively studied. It is a carcinogen as well as a toxin. In the human body, gyromitrin is converted to monomethylhydrazine, MMH, which can cross the blood-brain barrier and damage DNA.

To Spencer, the parallel between the ALS clusters in Guam and around Montchavin is inescapable: a poisonous natural foodstuff ... a toxin consisting of a hydrazine or hydrazine metabolite that chemically alters DNA ... eventual neurological disorder. He has authored or coauthored several papers arguing that the Guam findings support the French findings and that both, in turn, illuminate the broad importance of “genotoxicity” in not just cancer but also neurological disease: Compounds damage genes in specific ways and set events in motion that cause disorders months, years or decades later. “The mechanisms underlying cancer are probably pretty close to the mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative disease,” he says.

As far as Lagrange and coauthors are concerned, the risk of eating G. esculenta is clear. “It would be prudent to inform the public worldwide of the association with ALS,” they wrote in their 2021 paper, “and to recommend that False Morels (gyromitres) pose not only a short- but also possibly a long-term danger to health and life and, as such, they should never be consumed.”

Tasty but risky

While selling false morels is prohibited in Denmark as well as France, it’s allowed in Finland — and Finns relish the mushrooms. Markets sell freshly gathered false morels in springtime. Gyromitra esculenta was featured on a 1974 postage stamp. The Finnish Food Authority endorses the practice and instructs cooks to repeatedly boil and rinse fresh or dried specimens before eating.

In Finland, despite the hazards, some are fans of false morels, as this video describes.

CREDIT: DW FOOD

“It looks like something from an alien movie, but it’s delicious,” Kim Mikkola, then the chef of a Michelin-starred restaurant in Helsinki, said in a 2020 video that showed him collecting and preparing false morels. He says the fungi do contain neurotoxins and demonstrates the detoxification process. “If treated right it’s very good, acidic and a bit nutty. It has that kind of forest mushroom flavor ... a very elegant delicacy.”

In North America, false morels also have appeal, at least among a subset of foragers. “It may surprise you that Gyromitra esculenta is considered a delicacy in parts of the United States and in parts of Scandinavia,” one blogger notes. But a physician writing in the US-based magazine Fungi in 2020 cautioned that people who persist in eating false morels are merely “winning in a game of Russian roulette.”

The danger also applies to those who eat the fungi by mistake, thinking they are enjoying the true morel, Morchella esculenta, which bears a superficial resemblance to its more poisonous cousin. The risk has been amply documented in Michigan, where morel foraging is so popular the annual National Morel Mushroom Festival takes place in Boyne City.

In a study published in Toxicon in June 2024, researchers led by Varun Vohra, a clinical pharmacologist at Wayne State University School of Medicine and senior director of the Michigan Poison & Drug Information Center, documented 118 cases of false morel poisoning reported to the center between 2002 and 2020. In 90 percent of cases, the culprit was identified as Gyromitra esculenta. Gastrointestinal symptoms — vomiting, diarrhea, stomach pain — were most common. Over a dozen people experienced liver damage, one sustained kidney injury, and others reported neurological symptoms such as headache and dizziness.

The Michigan researchers, to be sure, were well aware of the French ALS cluster. In fact, one of the paper’s coauthors, Alden Dirks, a University of Michigan-trained mycologist who has closely studied gyromitrin-containing mushrooms, had provided the definitive identification of the false morels consumed by the patients in France.

A “growing body of literature has evoked concern regarding an insidious, chronic toxicity associated with gyromitrin exposure and a potential link to neurodegenerative disease,” the Michigan team wrote in their paper. “Future research is needed to explicate the nature of these associations, especially considering the high prevalence of ALS in the Midwest US and the regional popularity of [morel] consumption.” In its most recent analysis of ALS in the population, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranked Michigan as No. 6 in the United States, with an age-adjusted prevalence of 5.3 cases per 100,000 population (the US average was 4.4).

The challenge of establishing cause and effect in neurodegenerative disease is steeper than the winding road into Montchavin. Spencer and others realize the difficulty, particularly with all the years stretching between exposure and disease onset. And retrospective evidence seldom convinces everyone. As a clinical neurologist, Lagrange acknowledges that she isn’t equipped to perform the kinds of cell culture, animal modeling and genetic studies that would take the argument to the next level. Her colleague Camu, however, has started testing their ideas in lab mice.

For now, she says in a Zoom interview, “I think I did the job. I’m just a little doctor” — she holds her thumb and forefinger about an inch apart — “worried about the possibility of new cases in the village.”

And there have been no new cases of ALS, she says. “Hopefully, there’s no more.”

10.1146/knowable-121724-1

TAKE A DEEPER DIVE | Explore Related Scholarly Articles