Born in thin air: Overcoming the challenges of pregnancy at high elevation

In people not adapted to life at altitude, the sparse oxygen can impair fetal growth, causing problems that can last a lifetime. Researchers are searching for remedies.

Support sound science and smart stories

Help us make scientific knowledge accessible to all

Donate today

In 1545, Spanish colonizers greedy for precious metals established a mining town named Potosí in current-day Bolivia, more than 4,000 meters high (over 13,000 feet), at the foot of a mountain that was rumored to be made of silver. Those newcomers who settled at these heights didn’t exactly thrive: While Indigenous people were raising families, not a single child conceived by couples of European descent was born in the area for decades.

That’s because the thin air at high elevation contains less of the oxygen that fetuses need to fuel their development. Only about one-seventh of the oxygen the mother inhales is redirected to the placenta, which itself consumes 40 percent of it, passing on the rest to the fetus. Pioneering physiologist Joseph Barcroft famously compared the oxygen levels any fetus receives to Everest in utero — Everest in the uterus. At high elevation, that challenge steepens.

A growing number of scientists are now treading in Barcroft’s footsteps to better understand these issues. At a recent meeting in Cambridge, England, researchers convened to talk about what they’ve learned about the physiology and genetics of pregnancy at high elevation, and to exchange ideas on what might be done to help pregnant women whose bodies are struggling to provide enough oxygen to the fetus — be it at high elevation or low.

Low birth weight

One of the problems with pregnancy at high elevation is that mothers not genetically adapted to high-altitude living may not get enough blood flow redirected toward the placenta. Researchers have observed, for example, that Indigenous Bolivian women living at over 3,600 m (11,800 feet) had higher blood flow and babies of higher birth weight compared with people of European descent at similar altitudes.

Observations go back a long way, says Lorna Moore, an anthropologist and physiologist at the University of Colorado, who has studied this issue for more than 50 years and coauthored an early review of the field in the 1983 Annual Review of Anthropology. In Leadville, a Colorado mining town at 3,100 m (over 10,000 feet), scientists observed in the 1950s that babies of European descent had significantly lower birth weight than they did in nearby Denver (at 1,600 m or 5,250 feet). Moore and colleagues later found that blood flow to the uterus is about 30 percent lower in Leadville, even before fetal growth slows down.

Smaller babies face problems not only in the short term — an 8- to 20-fold greater risk of death in infancy — but often for the rest of their lives. People who were small at birth, researchers have learned over the past two decades, are at higher risk for a host of diseases later in life, from diabetes to hypertension and sudden cardiac death.

At 10,200 feet, the mining town of Leadville, Colorado, is the highest incorporated city in the United States. Researchers at the nearby University of Colorado have conducted studies there for decades to understand why pregnancy complications are more common at this height, and what might be done to prevent them.

CREDIT: ISTOCK.COM / CHAPIN31

Identifying the genetics behind people’s adaptations to high elevation may offer medically important clues. One area of focus is a protein called AMPK which, among other things, gauges the amount of energy available to the cell and helps to conserve and free up energy when necessary. A 2014 study led by physiologist Colleen Julian, also of the University of Colorado, found that at high altitude, Bolivian women possessing two copies of a certain variant of the gene coding for part of AMPK gave birth to babies that were about 20 percent heavier.

Reactive oxygen

Researchers are also looking more closely at mitochondria, the organelles in our cells that convert the energy found in fats and sugars into a form our cells can more easily use. The biochemical reactions inside mitochondria are a big source of reactive oxygen species, chemically reactive waste products that can damage our tissues. When oxygen is lacking, the mitochondria shift gears and churn out greater amounts of these molecules — which could partly explain long-term damage to the fetus.

The thin air at high elevation contains less of the oxygen developing fetuses need to fuel their development.

Giving antioxidants like vitamin C to pregnant rats has been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular issues in offspring born from low-oxygen pregnancies. But directly applying this insight to human pregnancies may have unintended consequences, says Kim Botting, a physiologist at University College London, because reactive oxygen species also play a role in increasing blood flow to the fetal brain when oxygen levels are low. Antioxidants might interfere with this helpful response.

Lovely wool

This is why Botting and colleagues at the University of Cambridge have turned to an antioxidant called MitoQ that was designed to be taken up specifically by the mitochondria. Once inside, it reduces the production of specific reactive oxygen species believed to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease in later life but does not interfere with reactive oxygen species produced elsewhere in the cell when there is a lack of oxygen.

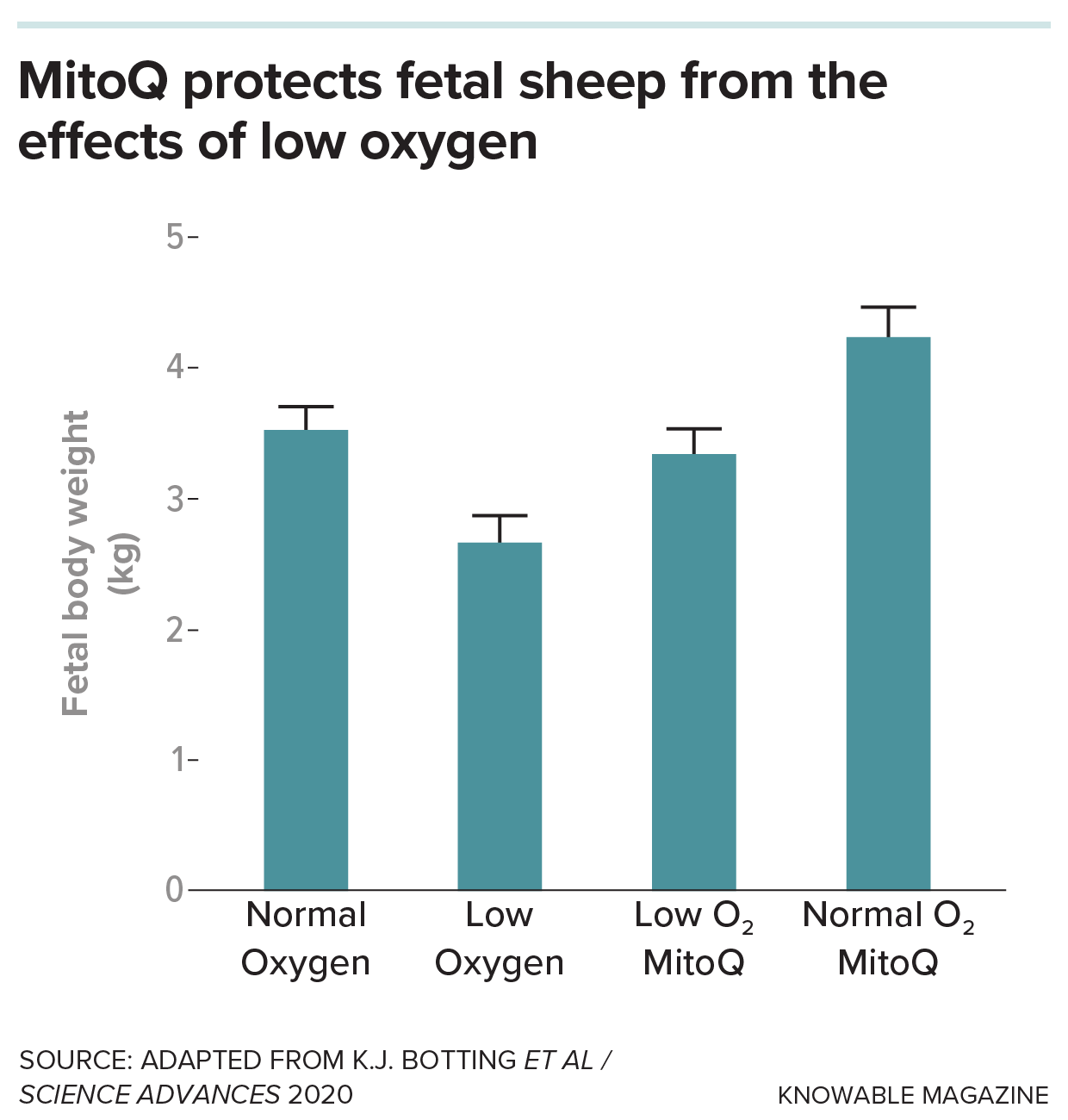

Researchers hoped that this would help to prevent the damage caused by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species without compromising the fetus’s ability to increase blood flow to the brain. And in experiments with sheep, it did: Birth weight of lambs born from ewes kept under low-oxygen conditions and treated with MitoQ was indistinguishable from that of ewes kept under normal conditions. (“They also have lovely wool,” says Botting. “We don’t know why yet.”)

The brain also looked normal, whereas low-oxygen lambs not treated with MitoQ had heavier brains relative to their body weight. Treated lambs also didn’t have the elevated blood pressure at nine months of age that is typical of lambs from low-oxygen pregnancies, suggesting that the treatment may prevent at least part of the cardiovascular issues resulting from lack of oxygen.

“We’d suggest that MitoQ may be an appropriate clinical intervention to diminish hypoxia-induced cardiovascular disease,” Botting said at the meeting. (One of Botting’s coauthors is a co-creator of MitoQ and consults for the company that produces it.)

Researchers gave the antioxidant MitoQ, which specifically targets the mitochondria of cells, to pregnant ewes held at low-oxygen levels and at normal levels. MitoQ, they found, prevents the decrease in birth weight usually seen in lambs exposed to low oxygen levels in utero. It also increases the size of lambs of ewes kept at normal oxygen levels.

Handle with care

The researchers plan to apply for funding to translate this work into a clinical trial soon. MitoQ is currently for sale as a dietary supplement, and the compound has already been tested in human clinical trials involving people with cardiovascular and neurological disease. But careful clinical studies will be required before the compound can be prescribed or recommended for pregnant women, and Botting certainly does not think anyone should use the product without the supervision of their doctor. “You wouldn’t want to be giving healthy pregnancies these sorts of drugs,” she says.

Further study of what goes wrong in pregnancy at high elevation or when the oxygen levels reaching the fetus are low hopefully will reveal new indications of when to intervene. These findings might be equally useful in treating fetal growth restriction and other disorders linked to impaired placental function or blood flow that can limit oxygen delivery to the developing fetus even at low elevation.

Doing such studies will always be difficult in people, Moore remarked at the Cambridge meeting, as studies involving pregnant women have to be done with utmost care. “But collaborations among us may be a way to make some headway. So let’s go, let’s begin.”

10.1146/knowable-031025-1

TAKE A DEEPER DIVE | Explore Related Scholarly Articles