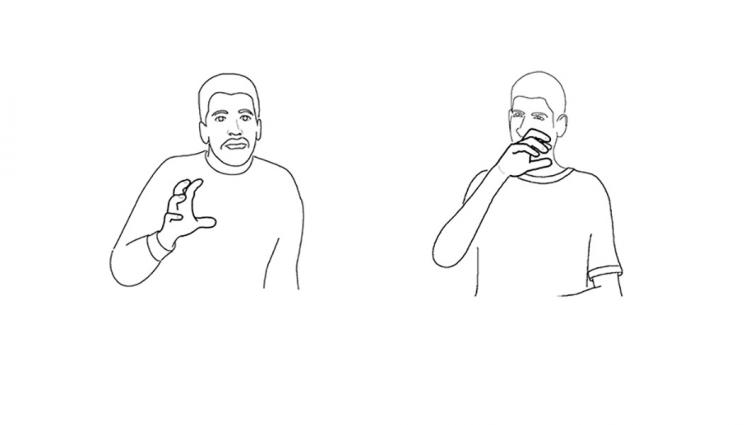

Men in the town of Al-Sayyid, Israel, use different signs for the word ‘dog’.

CREDIT: SIGN LANGUAGE LINGUISTICS LAB/UNIVERSITY OF HAIFA

Two men from the same little village in the Negev Desert sign the word dog — with quite different gestures. On the left, the gesturing hand is in front of the torso, and the fingers open and shut to indicate the bark of a dog. On the right, the hand is near the face, and the hands bend more slightly and rapidly in a flutter — again, to indicate that dog mouth. To a linguist, that difference signifies a young language on its way to maturity.

Both signs are in use in the Bedouin town of Al-Sayyid, in the Negev Desert of Israel. About 150 of the 4,000 residents are deaf, descendants of a hearing family to whom four deaf children were born more than 80 years ago. That’s 50 times the proportion of deaf to hearing individuals in most populations. As relatives intermarried, deafness spread and a brand-new language evolved: Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language.

Eighty years is just a blink of an eye for evolution of a language, so Wendy Sandler, a theoretical linguist at the University of Haifa, saw in Al-Sayyid an opportunity to learn more about the birth and blooming of a new sign language. The language had taken root among deaf and hearing people alike in the village, where both day-to-day and complex topics are discussed with ease — dreams, wedding plans, folk remedies, matters of finance.

Linguists have long been fascinated by sign languages, and curious to know whether these silent languages develop with the same kinds of rules that spoken languages share. All spoken languages, for example, have two levels of structure. One is the basic palette of vowels, syllables and other speech sounds that themselves bear no meaning — what’s called the tongue’s phonology. Level two is the meaningful words made by mixing and matching those sounds. That mix-and-match ability enables impressive vocabularies: English, for instance, has about 40 sounds that combine to form hundreds of thousands of words.

“It looked very fluent, although completely unintelligible to us.”

Wendy SandlerLinguists once debated whether signed languages had the same type of phonological structure, and thus the same large-vocabulary power. “If you look at a sign, it very often looks like what it means,” Sandler says. (The American Sign Language sign for book looks like a book being opened, for example.) The matter was settled in the 1960s: Yes, sign languages do have that expansive structure. But what about when a language first begins? Is complexity there from the start? Such a question can never be answered for spoken languages, which are either very old or descended from old tongues. But sign languages can emerge at any time. Al-Sayyid presented a tantalizing chance for Sandler to find out.

She fully expected complex phonology and conventionalized vocabulary at Al-Sayyid, because all languages have those traits. Languages, as a rule, are far more similar than different, as if certain structural elements of language are innate to human beings. And deafness was widespread in the community, so children had adults and older kids to learn from at a young age. Kids are rapid, adept language-learners.

“It looked very fluent, although completely unintelligible to us,” Sandler says of an early visit to the town. But it soon became clear that the language in many ways still lacked full structure and formality. There was, for example, a lack of uniformity in signs used by different families — as in the case for egg or dog. Another notable feature about dog: Height of the hand didn’t seem to carry additional meaning. Hand placement is very important in more-established sign languages: Just like a vowel or consonant in a spoken tongue, two different placements can totally alter the meaning of a word.

“It’s been fascinating, the extent to which we’ve been able to see a new language emerge with very little outside influence.”

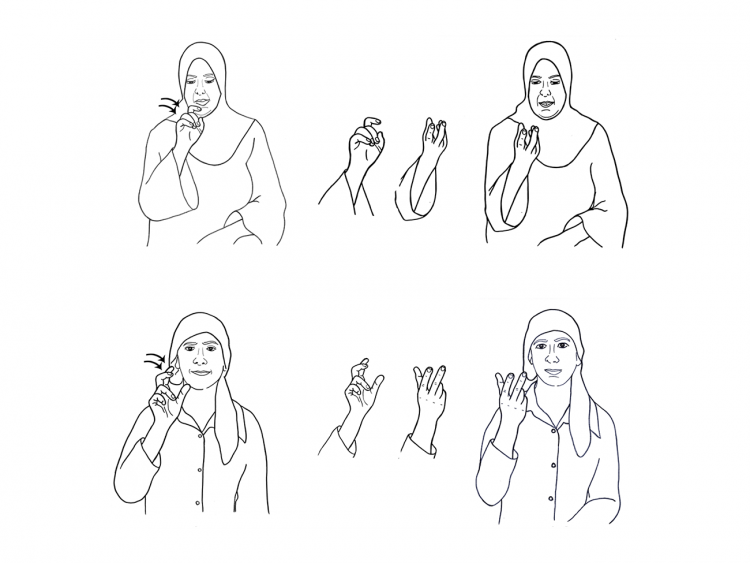

Wendy SandlerSandler and colleagues also documented the language’s developing complexity. Over time and in younger generations, signs lost their need to look like the object they were naming. Egg, for example, was signed by most of the community in two parts: first, a crooked index finger pecking downward — the sign for a chicken — then the hand flipped over with three fingers cupping an oval object. But one family had changed the first part of the sign to three pecking fingers. That’s far less like a chicken beak, but it flows more easily to the second part of the sign.

The two-part sign for ‘egg’ also varies in Al-Sayyid. Some (lower) use three pecking fingers for the first part of the sign.

CREDIT: SIGN LANGUAGE LINGUISTICS LAB/UNIVERSITY OF HAIFA

Younger generations also added movement — even meaningless movements — to their signs. Movement is a core feature of American Sign Language and Israeli Sign Language — of all established sign languages, in fact. It’s thought to make speech more fluid and easy to perceive.

“It’s been fascinating, the extent to which we’ve been able to see a new language emerge with very little outside influence,” Sandler says. That has changed: Schoolteachers hired from outside the village have introduced ISL to the community. And some of the deaf men work outside the village, while occasionally a deaf woman has left to marry in another part of Israel. A not yet fully formed language is now morphing, and with that comes new linguistic questions about how Al-Sayyid’s youth will incorporate ISL into their native tongue. “There’s lots of work to be done,” Sandler says.