When Oregon’s first psilocybin service center opened in June 2023, allowing those over 21 to take mind-altering mushrooms in a state-licensed facility, the psychedelic revival that had been unfolding over the past two decades entered an important new phase.

Psilocybin is still illegal on the federal level. But now, as researchers explore the therapeutic potential of psilocybin and other psychedelics, including LSD and MDMA (also known as Molly or ecstasy), legal reform efforts are spreading across the country — raising tensions between state and federal laws.

As a class, psychedelic drugs were outlawed in the United States by the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. The act designated psychedelics as Schedule I drugs — the most restrictive classification, indicating a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use. That status limits research to federally approved scientific studies and restricts federal funding to research with “significant medical evidence of a therapeutic advantage.”

Despite these limitations, researchers have demonstrated the potential of psychedelics in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety and addiction. A 2020 systematic review of recent research found that psychedelics can lessen symptoms linked to a variety of mental health conditions. While that review found no serious, long-term adverse physical or psychological effects from ingesting psychedelics, more research is needed on the latter.

Today, decades after research on the effects of hallucinogens on the brain was sidelined by the act, academic and cultural interest in psychedelics is on the rise. More than 60 percent of Americans now support regulated therapeutic use of psychedelics, while nearly half support decriminalization, and nearly 45 percent support spiritual and religious use. An estimated 5.5 million US adults use psychedelics each year.

In opening psilocybin service centers where adults can buy and consume “magic mushrooms” without a doctor’s prescription, Oregon took the biggest step yet toward expanding legal psychedelic access in the United States. In the process, it joined a growing number of states and municipalities that are carving their own paths with drug laws. Colorado legalized the use and possession of hallucinogenic mushrooms and three other psychedelics in 2022 and aims to open licensed use facilities by the end of 2024. And California’s legislature passed a bill in 2023 that would have legalized adult possession of psilocybin, the related psilocin and two other hallucinogens (dimethyltryptamine, or DMT, and mescaline), although Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed it in October, asking for legislation that focuses on therapeutic uses.

In all, 20 states introduced psychedelic-related legislation in 2023, ranging from plans to establish research councils and working groups to proposals to legalize use and possession of certain drugs. Meanwhile, cities in California, Michigan and Massachusetts have stopped enforcement or otherwise decriminalized possession of some psychedelics, typically ones that are naturally found in plants and fungi. Washington, DC, the seat of the federal government, has also loosened its psychedelic laws.

Some of these reform efforts aim to revive research that might lead to badly needed mental health treatments; others are pushing back against what many deem unfair criminal punishments stemming from the “war on drugs.” The result is a growing patchwork of state and local laws that stand in conflict with the Controlled Substances Act.

What does the future hold? Robert Mikos, an expert on drug law at Vanderbilt University Law School in Tennessee, says the history of marijuana law reform may offer some indicators.

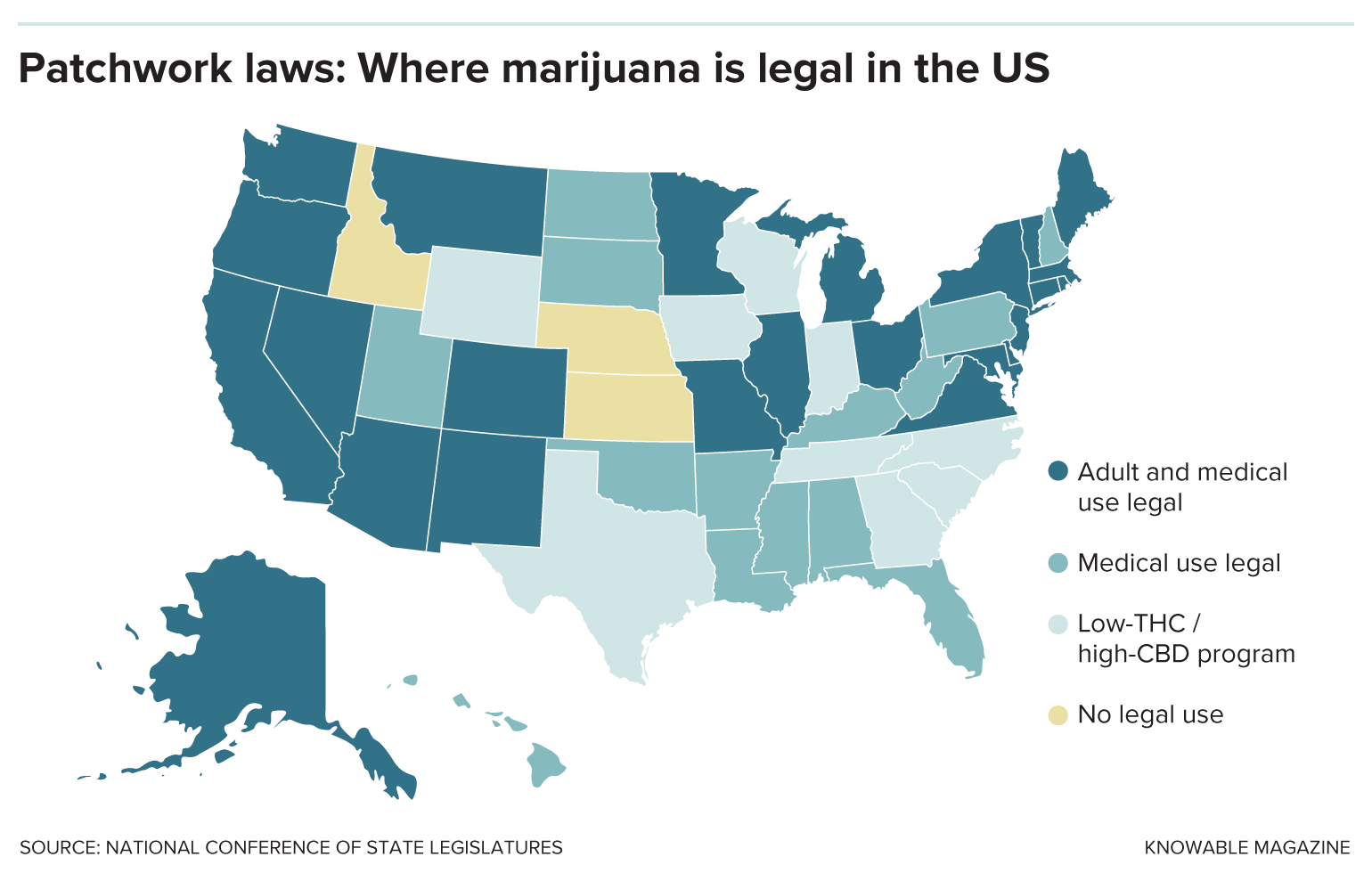

In 1996, California voters approved the medical use of marijuana, and today 38 states have medical marijuana programs, while 24 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational use. Seventy percent of Americans support marijuana legalization, up from about 25 percent when California first changed its law. And yet marijuana, which is sometimes itself considered a psychedelic, remains a Schedule I substance.

Thirty-eight states have legalized medical use of marijuana, and 24 of those now also allow adult recreational use. Other states permit sales only of low-potency cannabis.

For marijuana, too, public perception underwent dramatic shifts as research demonstrated its relative safety and effectiveness for the treatment of pain and nausea, among other maladies.

Mikos analyzed the implications of marijuana reform history for the legal future of psychedelics in the 2022 Annual Review of Law and Social Science. In an interview with Knowable Magazine, he explored the path toward rescheduling, why different types of psychedelics need to be considered separately, and the interplay between federal and state drug laws.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What have you learned from studying the history of marijuana reform in terms of what’s now happening with psychedelics?

The biggest lesson is that you don’t have to put all your eggs in one basket and get the federal government to sign on, which is extremely difficult to do. The states provide an alternate forum for pursuing reforms. We’ve seen some small changes to federal law, but in the last 26 years or so, we’ve seen the states figure out ways around all the obstacles erected by the federal government. There are some compromises and sacrifices that have to be made to work around federal law, but you can pull this off and have meaningful reform without agreement from the federal government — even with some hostility from the federal government.

Do you think the legal journey of marijuana should inform the future for psychedelics?

There are differences here. No one even agrees on what the term psychedelics encompasses. Some people think immediately of plant-based psychedelics like psilocybin. Others would include lab-made drugs like LSD. It’s a much more diverse array of substances than marijuana. If someone wants to legalize psychedelics, they may have to pick one substance and run with it. That is a clearer path to success than saying you’re going to legalize all psychedelics. I don’t think any state would be willing to do that at this point.

Framing its use as medical helps — that was certainly true with marijuana. It’s much easier to sell the public on legalizing something for medical use rather than recreational or spiritual use. Under the Controlled Substances Act, the only lawful use of a controlled substance is medical, so there was a natural inclination to frame marijuana use as medical.

Politically, it would be easier to convince a majority of the public to support a ballot initiative to legalize some psychedelics, like psilocybin, for medical use. It would be a simpler story than saying, “Some people here want to go out and trip.”

In Oregon, psylocibin can now be taken at a state-licensed center under the guidance of people trained to facilitate users’ psychedelic experiences. Here, students in training to work as psylocibin guides wear sleep masks as part of a class exercise.

CREDIT: LIZZY ACKER / THE OREGONIAN

In 2023, the US Department of Health and Human Services, which is tasked by the Drug Enforcement Administration with reviewing the medical and scientific evidence for a drug’s scheduling, recommended reclassifying marijuana from Schedule I to Schedule III, indicating federal recognition of its accepted medical use. That move would open the door to federal approval of medical marijuana but keep it criminally controlled. Could that be a path for psychedelic reform?

If the Drug Enforcement Administration does reschedule marijuana, it would show that you could get this done at the federal level — but consider that the Controlled Substances Act was passed more than 50 years ago. Marijuana could still end up moving only one rung, to Schedule II, which is very tightly controlled — cocaine is there right now. My takeaway is: Don’t hold your breath waiting for the federal government to change its laws.

And for psychedelics, it’s more complicated. You’d need to make that same demonstration to the Food and Drug Administration — that the drug has medical uses — for each and every drug you were interested in. (The FDA evaluates a drug’s safety and medical efficacy, as well as potential for abuse, among other factors, in its analysis.)

Still, there’s at least a sign, now, that you can convince the federal government to lower the controls on some of these long-forbidden substances. But given how much time it’s taken and how limited that impact would be, it suggests you need to do something else — probably going through the states again and not the federal government.

To what extent is the Controlled Substances Act dictating the trajectory of psychedelic reform?

The Controlled Substances Act privileges medical use, which is going to frame the debate around these substances. But I think people are going to shoehorn in uses that are not genuinely medical uses of the drug.

People are trying to scientifically test these drugs, but ironically, the Controlled Substances Act makes that very difficult. If a drug is on Schedule I, to move it off you need clinical trials demonstrating that it’s effective at treating some medical condition. But conducting those medical trials is really difficult because it’s Schedule I.

The federal government wants to make sure that something someone says is going to be used in a clinical research trial is not sold on the black market. So it imposes special controls, which it could relax to make it easier for universities, hospitals and scientists to test the medical efficacy of different psychedelics.

Even though psychedelics are often discussed as an entire class of drugs, they differ in their chemistry, how they’re created and how they affect individuals who take them. How will that influence the way advocates approach reform?

At the federal level, even if you conduct mountains of research demonstrating that LSD has some accepted medical use, that won’t have any effect on whether to reschedule psilocybin. Politically, it may be difficult to form alliances in that situation between people who believe strongly in legalizing psilocybin versus those who support legalizing a different psychedelic drug.

At the state level, it could get tricky. Will there be enough people out there who are willing to support an initiative targeted at just one of these psychedelics? We don’t have much public opinion research on psychedelics in general, and certainly not on individual psychedelics, which may be the route that reformers need to take.

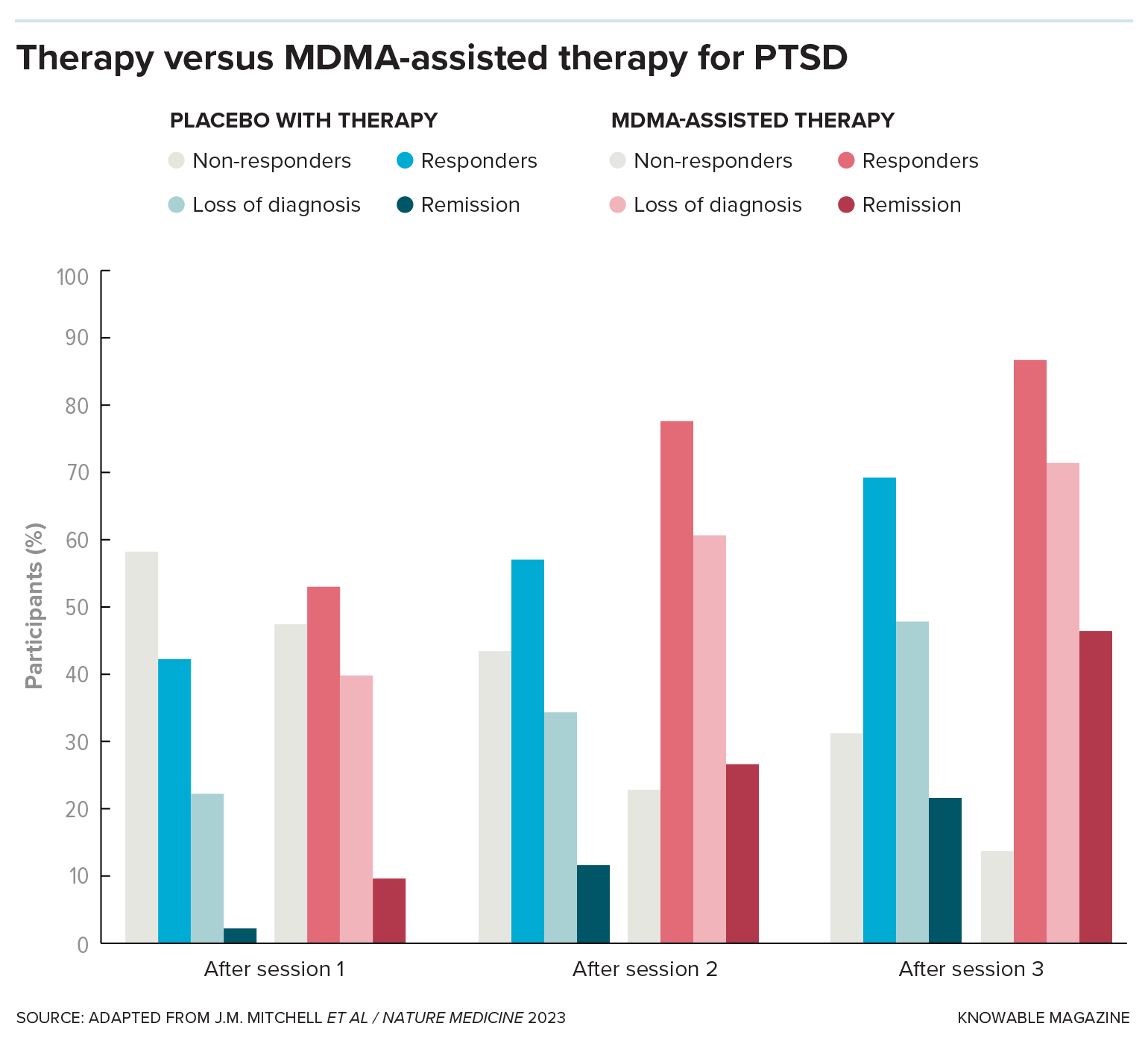

MDMA was granted “breakthrough therapy” status in order to be studied as part of treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder, and the completion of a Phase 3 trial in fall 2023 means it could be approved by the FDA for this use as early as 2024. Would that require the drug to be rescheduled? And how would that change the trajectory for psychedelics overall at the federal level?

It would necessitate rescheduling. You can’t keep a drug on Schedule I if it has accepted medical use. Which other schedule it falls on depends on the relative harms and likelihood of abuse. But I’m not sure there are broader ramifications. The Controlled Substances Act calls for the scheduling of individual substances, rather than classes of substances, so the scheduling of MDMA has no implications for the scheduling of psilocybin.

A Phase 3 clinical trial found that MDMA-assisted therapy reduced participants’ symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and functional impairment better than placebo — a major advancement in efforts to show the therapeutic potential of psychedelics.

What does the tension between state and federal psychedelics law look like?

It’s a bit like a chess match. The states can liberalize their laws and allow people to use, manufacture and distribute some psychedelics, such as psilocybin in Oregon, without fear of arrest from the state government.

The federal government could try to counter the states by making it very difficult for the states to regulate psychedelics. This was true in the early days of state marijuana law reforms. The states wanted to create a safe and heavily state-regulated supply system, but the federal government was threatening to crack down on suppliers, so states didn’t try to set up regulated supply systems. In California, for example, people set up enormous collectives that served tens of thousands of patients, but those suppliers weren’t regulated to the same degree they are now.

You saw state regulation take off only around 2009 when the Obama administration announced it would stop raiding medical marijuana distributors. But that was more than 12 years into state marijuana reforms. Prior to that, states said, “We’re going to call your bluff.… We’re not going to arrest patients. Instead, we’re going to tell patients to grow it themselves, get it from a friend or the black market.”

That’s less than ideal. The states didn’t want some 70-year-old terminal cancer patient having to grow their own medicine, but they said that’s better than threatening to arrest that patient. You might see a similar tit-for-tat in the psychedelics realm.

Oregon has tried to jump the gun a little bit with psilocybin. What they’re envisioning is a tightly regulated state supply system. You can’t buy it and use it at home at your leisure — you have to use it at a state-licensed psilocybin service center.

The problem with that is that it’s much easier for the federal government to shut down state-regulated suppliers because you’ve got a list of them, so it puts those suppliers in harm’s way. They can be arrested, prosecuted, thrown in prison for long terms and have their assets seized.

But if the federal government cracks down on those psilocybin service centers, Oregon might just lift its prohibition on making and distributing this drug. And then the federal government might come back to the table, as it eventually did with medical marijuana.

It’s a back-and-forth between the states and the federal government to figure out how much the federal government will tolerate.

A marijuana dispensary in New Orleans, Louisiana, one of 38 states that have legalized medical use of the drug.

CREDIT: WILLIAM A. MORGAN / SHUTTERSTOCK

What lessons have we learned from the early stages of psychedelic law reform?

Oregon passed Measure 109 back in fall 2020. It took three years for the first psilocybin service center to open. It takes time to figure out how to do this, especially for early adopters. Can we actually have a system where the state is looking over your shoulder while you’re taking this drug? Or is that going to backfire and is the federal government going to use that to crack down on these centers?

As long as the sky doesn’t fall and you don’t see some disasters from these early adopters, I think other states will warm to it. But the first few years are going to be slow going.

Are there indications yet about whether psychedelics will be able to gather the same kind of political backing that helped push marijuana reform?

I am deeply skeptical. If you look at marijuana, we’ve had the majority of Americans support legalization for recreational or adult use for 10 years and we’re just now getting some tepid indications that somewhere down the line the Biden administration might change federal law governing marijuana to allow for medical use.

It’s going to take a while before you get that sort of public support for psychedelics reform, if you ever get it, and you’d need that before whoever is in federal office 10 to 20 years from now actually embraces this.

The forecast at the federal level doesn’t sound favorable for reform advocates, but at the state level, do you think psychedelic reform is inevitable at this point?

Not necessarily. Psychedelics aren’t nearly as popular or familiar to the general public as marijuana is, so advocates of reforms will have a bigger job educating the public and convincing them that legalization is a good idea.

I don’t think we’re going to see a sudden rush to embrace psychedelics. You might see it in a few states like Oregon and California. Other states will wait on the sidelines and see how it works: Did they figure this out? Is it safe? Is it effective? Were they able to control it? Once you see that demonstration you might see some momentum pick up, especially if public support for psychedelics grows.

A decade from now, maybe seven or eight states will have legalized one psychedelic, probably psilocybin, ostensibly for therapeutic use but, in reality, for any use, as Oregon has done. And then maybe the federal government will reschedule one of these psychedelics. But this took 25 years for marijuana. It will probably be similar for psychedelics.