In 2008, gastroenterologist Colleen Kelly had a patient with a recurring and debilitating infection of the gut with a microbe called Clostridioides difficile. Nothing Kelly did could ease the woman’s severe abdominal cramping and diarrhea.

So Kelly — at her patient’s urging — decided to try something highly experimental: transplanting a fecal sample from a healthy donor into the large intestine. And it worked.

Kelly, of Brown University School of Medicine in Providence, Rhode Island, is now one of the leading doctors performing the procedure. She has done about 300 fecal transplants in the last decade, with good success — and has even, she says, seen ICU patients with the most severe form of the infection sit up and ask for food within a day of their transplant.

Today’s data show that fecal transplants cure 80 percent to 90 percent of patients with recurrent C. diff infections — and doctors across the globe have accepted them as a legitimate medical treatment. The procedure is considered experimental (no regulatory body in the world has officially approved it outside of investigational protocols), but hospitals now perform fecal transplants for up to 10,000 cases of recurrent C. diff infections per year in the US alone. OpenBiome, a nonprofit in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that collects and rigorously tests fecal donations from volunteers, has shipped more than 48,000 such samples in the last six years.

A recent death — likely the first one caused by a fecal transplant — from an inadequately vetted sample underscores the need for scrupulous screening, experts say. That’s especially so now that researchers are assessing whether fecal transplants can effectively treat other gastrointestinal disorders, or even conditions less obviously related to the microbes that live in our guts.

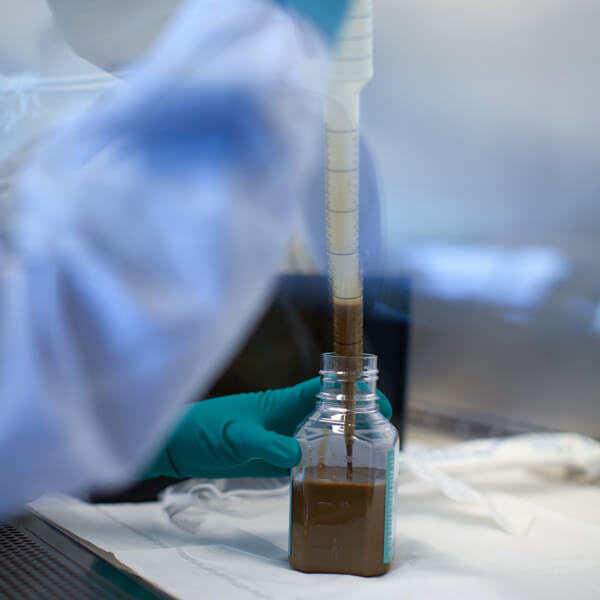

A lab technician at the OpenBiome stool bank fills a treatment bottle with a donor stool sample that has been screened for more than two dozen infectious agents and blended with a solution of saline and freezing protectant.

CREDIT: OPENBIOME – ERIK JACOBS / JACOBS PHOTOGRAPHIC

Hostile takeover

C. diff infections can take hold when the normal flora in a person’s gut — the gut microbiome, or microbiota — is disrupted in some way, usually after taking broad-spectrum antibiotics. Without a healthy bacterial community to keep it in check, C. diff can take over, causing diarrhea from the toxins it exudes, abdominal pain, inflammation and even life-threatening sepsis. Patients are usually elderly and the sickest among them, with the most severe forms of C. diff, are often on life support, and half will die. Measures to save them may include surgical removal of the colon.

Treatment with further antibiotics will often knock back C. diff growth and cure the problem in many people, but some patients have recurring bouts of infection and have found relief only after a transplant of the mix of bacteria from a healthy person’s gut.

To perform a transplant, physicians acquire a donor sample, typically from a stool bank such as the Netherlands Donor Feces Bank or OpenBiome. The samples are rigorously screened for infectious diseases: Of those submitted to OpenBiome, less than 3 percent get through, says Zain Kassam, who developed the nonprofit’s screening protocol as cofounder and former chief medical officer. The sample is then given to the patient via a stomach tube, colonoscopy, enema or, in some cases, a series of capsules.

For C. diff patients, it doesn’t seem to matter which route of administration is used or what mix of bacteria is in the donor fecal sample. Irrespective of the details, “it seems to be enough to reinstall a diverse, healthy gut microbiota,” says Josbert Keller, a gastroenterologist at the Haaglanden Medical Center in The Hague, Netherlands, who coauthored an overview of fecal transplants in the 2019 Annual Review of Medicine.

In fact, it remains unclear just how the transplants work: “We have a strong speculation that the community of bacteria matters, but we have yet to identify the key molecules and metabolites,” Kassam says. Still, he adds, that’s not so unusual — physicians have administered many drugs before fully understanding their mechanisms. “You don’t need to know how to fix the engine to drive a car,” he says.

And the transplants are surprisingly simple for hospitals to administer. “Yes, poop’s a biohazard, but we’re an endoscopy unit — we’re used to it,” Kelly says. When handling donor samples, whether fresh or frozen, she gowns up with gloves and mask as she would for handling any biological material. (She often prepares the sample “around the corner” so patients don’t have to watch.) Cleanup is no different than for any other hospital scenario involving human waste.

Many physicians now consider the procedure safe and effective, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends it for treating recurrent C. diff infections in adults and children. And though the treatment has not received formal approval from the US Food and Drug Administration, the FDA has granted a special exception for use of the transplants in recurrent C. diff cases.

Some gastroenterologists caution that fecal transplants are still experimental and considered treatments of last resort by hospitals. Indeed, in June the FDA released a safety alert after two immunocompromised patients in a clinical trial became infected by a multidrug resistant form of Escherichia coli that was traced to their fecal transplant donor sample, which had not been tested for the microbe. (Stool repositories such as OpenBiome screen samples for that specific organism.) One patient died from the infection — the first reported death attributed directly to a fecal transplant treatment.

The procedures are not covered by most insurance, leaving the cost — which runs to several thousand dollars — to hospitals or patients. Some patients have resorted to do-it-yourself fecal transplants using a family member’s stool, a blender and an enema bottle, but physicians strongly discourage this due to the risk of unknown infections.

Fecal transplants for other disorders?

Given the relative success and strong safety record to date, researchers are now branching out to test whether fecal transplantation might be helpful for other diseases beyond C. diff. One possibility is end-stage liver disease, when the gut microbiota often contains an excess of ammonia-producing microbes. That leads to a “leaky gut” that allows toxins that build up in these patients to seep into their bloodstream. As the molecules hit their brains, these patients experience episodes of dementia-like confusion and other cognitive and motor impairments, a condition known as hepatic encephalopathy.

Jasmohan Bajaj, a liver transplant physician at Virginia Commonwealth University and McGuire Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Richmond wondered with his colleagues whether a fecal transplant could help in such cases and reduce the number of episodes of confusion. The team gave standard treatment — antibiotics along with laxatives, to flush toxins — to 20 patients, half of whom received a fecal transplant. The donor sample was selected for a high abundance of two types of bacteria that are depleted in hepatic encephalopathy.

During the next year, the patients receiving fecal transplants had only one new episode of encephalopathy, compared with 10 episodes in the control group, the team reported this year in Gastroenterology. No adverse side effects related to the transplant were reported. Bajaj’s team soon will be enrolling 100 patients through the Richmond VA system for a more extensive trial.

Researchers are particularly keen to test whether fecal transplants could be used to treat inflammatory bowel conditions such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, which also involve a loss of microbial diversity in the gut.

A handful of clinical trials have tried fecal transplants for ulcerative colitis, and early results have been promising. A 2017 meta-analysis of four trials involving 277 patients with mild or moderate symptoms found that 28 percent of those who received a transplant experienced remission from blood in the stool, diarrhea, and fecal urgency, compared with 9 percent of those who received standard care. Kassam says results from some of these studies are as good as for other new drugs that have recently been approved for ulcerative colitis.

As research into fecal transplants has increased over time, so has the number of disorders being tested with the treatment. A survey of 246 clinical trials found that in 2010 and 2011, fecal transplant studies were focused on fighting C. difficile infections and inflammatory bowel disease. By 2018, the research landscape had expanded to testing fecal transplants for numerous health conditions, including gut-brain axis disorders, diseases of the liver or pancreas, irritable bowel syndrome, infectious diseases, metabolic diseases and infections by multidrug-resistant organisms.

But that’s not yet enough to convince him to prescribe the experimental treatment for his father, an ulcerative colitis patient. For one thing, these preliminary studies hinted that fecal transplants are helpful only for some ulcerative colitis patients and that some donor samples work better than others. Researchers also haven’t yet worked out whether patients should receive immune-suppressing steroids too, or whether they will need repeated, maintenance transplants to stay healthy.

Kassam can envision a more precise microbiota treatment for ulcerative colitis in the future. He co-founded a company — Finch Therapeutics in Somerville, Massachusetts, where he is now executive vice president for clinical development and translational medicine — that aims to identify the bacteria, or the byproducts they make, that are causing success in patients and package just those elements into capsules. By sequencing all of the bacterial genes present in fecal samples and cross-referencing them to successful transplants, researchers could winnow down the list of helpful elements and toss out parts of the sample that are truly waste. This might deliver more targeted treatments.

Other medical conditions also involve changes to the gut microbiota, including surprising ones such as the cluster of conditions linked to obesity and inactivity known as metabolic syndrome, as well as autism spectrum disorder and multiple sclerosis. Though very tentative, some studies suggest that fecal transplants may be helpful — for example, in one study of 18 children with autism who all received fecal transplants, all showed improvements in gastrointestinal and behavioral symptoms compared with baseline scores before treatment. Changes persisted two years later, at which point recipients retained at least some bacteria from the donor stool. But this was not a randomized, controlled trial — the gold standard for determining if a treatment is effective — and others like it are preliminary, small and far from conclusive, so experts say it’s too early to make much of them.

Kelly, for her part, describes herself as a “big believer” in the use of fecal transplants to treat C. diff, but she’s much more cautious about using them for these other disorders. She and others worry that for some people with inflammatory bowel diseases, fecal transplants could make their condition worse.

And they note that fecal transplants have been in widespread use for only a decade, so their longer-range consequences are unknown. Could they introduce hidden pathogens, or cause rare but serious side effects that show up later? That may not be an issue for older people, “but for younger people it makes sense to think about the long term,” Kelly says.

To get at the potential side effects, the American Gastroenterological Association has set up the Fecal Microbiota Transplantation National Registry, which Kelly spearheads, to track 4,000 fecal transplant patients of any kind in the US. The registry will collect baseline data about the patient and donor, how the transplant was done, whether it worked and any adverse events, then follow up regularly for 10 years.

Keller agrees that doctors should proceed cautiously until potential downsides of the treatment are better understood. “If we are trying to treat patients with multiple sclerosis, ulcerative colitis, Parkinson’s disease or autism with fecal transplants and altering their microbiota, then we should also be very careful that we do not induce other disorders,” he says.

He adds that he frequently gets emails from people requesting fecal transplants for their children with severe autism. “I can understand how desperate parents are,” he says. “But I don’t believe the time is right yet. This is still completely experimental.”

Editor’s note: On July 26, 2019, the credit for the OpenBiome chart on fecal transplant studies was amended to note the publication source and date.