Infectious disease expert Anthony Fauci. Coronavirus response coordinator Deborah Birx. County health officials across the United States. The Covid-19 pandemic has led to the emergence of a new set of household names: those in the media spotlight who are charged with helping the public understand what is happening, what is likely to happen next, how to behave to reduce the pandemic’s spread, and why.

Through these health officials, millions have heard about social isolation, flattening the curve, mask-wearing, vaccines, antiviral drugs and more.

The footing is tricky: Downplay a threat and the public might not react strongly enough; overdo it and they might not listen next time. And how can officials remain trustworthy when scientists’ understanding of a new virus is changing by the week?

Deborah Glik, a health-communication researcher at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, has spent decades studying the art and science of informing the public during health emergencies, a topic she wrote about back in 2007 in the Annual Review of Public Health. Over the years, Glik has helped the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention develop communications plans for a wide range of health hazards, including bioterrorism agents such as botulism and plague. Knowable Magazine spoke with Glik about the key principles that guide public health officials in their messaging, with special attention to the current pandemic.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What are the goals of public health communication in a pandemic?

The goal is to get as much information as possible out to as many people as possible, as quickly as you can. That means the messages themselves have to be simple. However, in risk communication a lot of the messages are not simple — they rely on technical concepts like “flattening the curve” or “contact tracing” that some people may not understand at first. Therefore, the initial messages generally focus on what is happening, what to do, how to do it, where to find information and who’s doing what. Once that “what” is out there circulating, then the “why” can be integrated in.

We have a technique — actually, it comes out of public relations and politics but it was adapted about 20 years ago in crisis and emergency risk communication — of “talking points.” Prior to official release, a group of people in charge decide the central ideas they want to communicate to the population. Generally, the rule of thumb is, if you’re talking about basic survival issues, you want no more than three or four points at a time.

You back it up with evidence. If you’re saying to wear a mask, your evidence would be that studies have shown that people wearing masks are less likely to spread the coronavirus. If you’re saying to wash your hands, it’s that this prevents the spread of germs. The idea is, you have basic messages, but you weave in the explanations for why you’re doing it.

“Wash your hands” and “wear a mask” are simple messages. Social distancing gets a little more complicated, but it’s still reasonably simple. But now let’s get to a less simple concept, “flattening the curve.” Understanding why you would do that assumes, first of all, that you know what a curve is, so you have to use graphs and explain what they represent. Then there’s the issue of hospital surge. Unless you’re a student of public health or disasters, you wouldn’t understand what that means.

That’s why we wait on the more complex ideas until people are fully invested in the simpler ones. It’s taken a lot of energy and effort to help people understand that much of what’s being done right now, in terms of public health, not only reduces transmission and cases but also avoids overwhelming hospital systems.

“Flattening the curve,” to avoid overloading the health care system, is one of the more sophisticated concepts that health officials have had to communicate to the public during the Covid-19 pandemic. The fact that so many of us now understand its importance is a major success of coronavirus communication to date.

CREDIT: SIOUXSIE WILES AND TOBY MORRIS / WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Are pandemics different from other public health issues?

Regular risk communications generally have to do with personal health issues like smoking or things like sexually transmitted diseases or tuberculosis. Generally they are focused on reaching high-risk groups of people. So you have target audiences, you do marketing, you do outreach. Those are everyday risk communications.

Here’s the difference: In an emergency, everybody’s at risk — or at least, everybody in a certain area. Most emergencies are regional or local, but they’re collective, in the sense that a lot of people are at risk, and it’s not necessarily because of something they did or didn’t do.

And emergencies are newsworthy. Covid-19 is exceptional, however, because it co-opted all the news media all the time, which is not normal. So we didn’t have to focus on making people aware of the problem, we could focus on what they should do — to help them adopt and maintain risk-reduction behaviors such as wearing masks and social distancing.

How much advance planning goes into a pandemic communications response?

A lot of those pandemic plans were in place years ago. We were very concerned after the SARS epidemic in 2002-03 that we were not ready for a global pandemic. A lot of messaging was developed, particularly around hygiene — stay home if you’re sick, wash your hands, get the flu shot. We imagined shelter-in-place a little bit: Certainly, Mexico City did a shelter-in-place order during the first weeks of the 2009 swine flu epidemic. But we were thinking two weeks! That’s what’s very different about this. It’s a much longer, much more widespread threat.

Do you have to scare people to get them to take action?

There was a debate for years about whether to use fear in health communication. The consensus is, it depends on the threat and how imminent it is. In everyday risk communication about things like smoking or overeating, you don’t overhype the fear — there’s a concern you can make it so fearsome that nobody wants to listen to you.

You don’t have that issue in emergencies that are life-threatening right now. The large majority of people are eager to learn. They’re open to information, as long as it’s chunked out in a way that doesn’t overwhelm them. And that’s why you parcel it out. You can’t tell everybody everything all at once. But if you guide people along and educate them, not patronize them, the large majority of people will in fact listen. That’s exactly what we’ve seen.

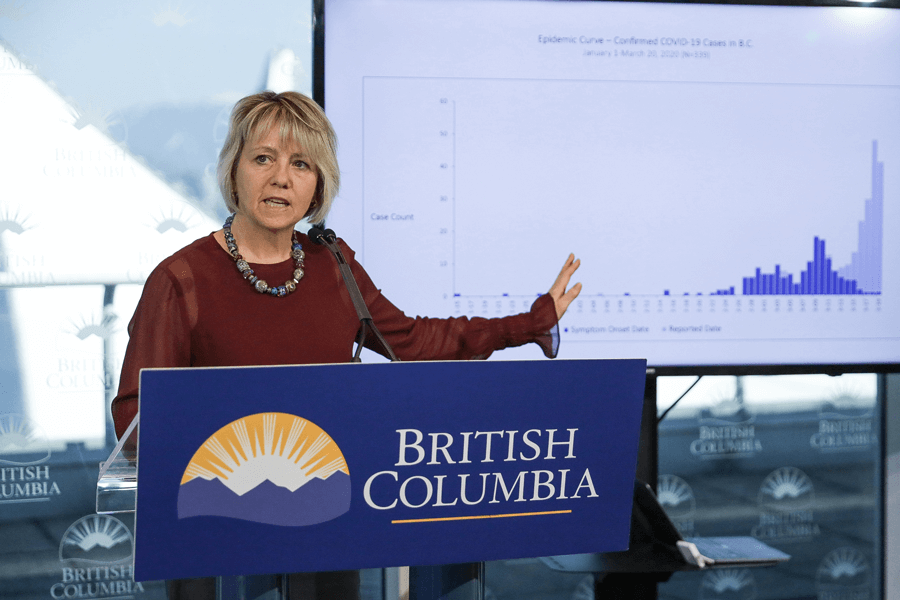

Bonnie Henry, chief health officer of the Canadian province of British Columbia, has won widespread praise for her clear, honest and compassionate leadership in that province’s so-far successful effort to control Covid-19.

CREDIT: PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA / FLICKR

How much should you tailor messages for different audiences?

What we find in public health messaging is, the more you can tailor it to a person’s specific life situation, the better. But it’s very hard for a health department to tailor messages for everybody. Ideally, we have partners — schools, universities, community-based organizations, faith-based organizations — who take our messages, think about their population and say, this is how it applies to us, here’s what we’re going to do. In my university, we’ve been hearing very specific messaging for months now about issues like how to come to your office if you need to: making sure you wipe down the door handles, not staying too long, staggering arrival times, those kinds of things.

These targeted messages are important as businesses open up: Here’s what our employees need to do, here’s what our customers need to do, we’re not letting customers in without masks, there have to be partitions. Part of this is a learning curve. We’re making this up as we go along. We did pandemic planning for years, after SARS and H1N1 flu, but nobody got down to many of the practical issues that we’re dealing with now, because we didn’t think that far ahead.

How do you deal with disinformation and misinformation? Should you just ignore it to avoid making it more salient?

You don’t keep quiet if myths and misinformation are being promoted. You absolutely push back. And you do it in a way that’s smart and consistent. After the anti-vaxxer movement became vocal in the late 1990s, public health people started, over time, to be more consistent, more forceful and more evidence-based. They kept pushing, and although there still is an anti-vaxxer movement, the threat has been minimized.

Covid-19 has had a lot of misinformation, and it was backed up by the White House: that it was a hoax, that it was never going to come to America, that we were prepared, that hydroxychloroquine was a cure, and of course the bleach and disinfectant. But there was a big pushback. In California, the mayor of Los Angeles, the governor and public health officials put out messages that “This is the real thing, we have to social distance, we have to avoid hospital surge.”

Public health officials depend on partners such as schools, churches and businesses to apply general guidelines to their own audiences and circumstances. Here, a church in Tulsa, Oklahoma, reinforces one of the basic health messages of the pandemic.

CREDIT: JOHN CLANTON / TULSA WORLD

But what if the conflicting messages reflect our evolving knowledge? First we heard that face masks weren’t effective, then we heard that they were ….

You have to walk things back and say, “You know what, in February we didn’t know about face mask efficacy, now we do.” A better thing to have said in February might be, “We don’t know how effective masks are; we’ll make a decision when we have the data.” If you listen to great emergency risk communicators, they tell you only what they know. If you don’t know something, you don’t make stuff up. You say: “We’re working on that, we don’t know, we will get that information to you as soon as we have it.”

Can you point to examples of Covid-19 communications that were done especially poorly?

Any kind of inconsistent messaging is bad. If you’re hesitant about the seriousness of this threat, or say one thing at one point and another thing at another point, that is inconsistent messaging, and it erodes trust and credibility.

With the federal government there was a lot of conflict, a lot of inconsistency, and there was some lying and making things up. I think Fauci and Birx, as White House advisors, did well enough under the circumstances. But our President has had opportunity after opportunity to show that he can communicate in a way that’s responsible, consistent, credible, empathetic. This was his big test, and he flunked.

And on the bright side, who’s done well?

If you look at the best communication after an emergency, it usually comes from local officials and people with expertise on the issue. They know the community and the topic. In Los Angeles, our county health director, Barbara Ferrer, has given excellent, very calm, very consoling advice and ideas and instruction on a regular basis. Governors, mayors, public health directors, epidemiologists and medical personnel have stepped up and been the mainstays. This makes total sense from a risk communication perspective.

This article is part of Reset: The Science of Crisis & Recovery, an ongoing series exploring how the world is navigating the coronavirus pandemic, its consequences and the way forward. Reset is supported by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.