Anxiety. Depression. School failure. Self-harm. Unemployment. Unplanned pregnancies. Even an increased risk of early death.

The risks and toll of suffering that can come with having attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, is huge, counted annually in billions of dollars in lost productivity and health care spending and in untold frustration and failure.

Yet despite more than a century of research and thousands of published studies, ADHD — marked by distraction, forgetfulness and impulsivity — remains largely misunderstood by the public. This is especially true when it comes to girls and women.

Over the past few decades, pediatricians, teachers and parents have gotten a lot better at spotting ADHD in girls. In the 1990s, scientists believed it was as much as nine times as common in boys, and very few girls were diagnosed. Today’s diagnosis rate has narrowed to 2.5 boys to every girl.

The diagnosis of ADHD in the United States has surged in recent years, though current numbers are probably higher than its true prevalence. Estimates suggest that worldwide, 5 to 7 percent of youth have ADHD. The higher rates of diagnosis in the United States are probably due to several factors, including shifts in educational policies that emphasize student test scores and changes in medical benefits coverage.

Still, an old problem persists. Whereas many boys with ADHD are normally more physically restless and impulsive, traits clinicians refer to as “hyperactive,” many girls with the disorder may be more introverted, dreamier and distracted — or in clinical jargon, “inattentive.” In part due to these subtler symptoms, experts suspect that many girls with ADHD are still escaping notice — and missing out on treatment.

“Who gets noticed as having ADHD?” asks Stephen Hinshaw, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, and a leading researcher on ADHD in girls. “You get referred if you’re noticeable, if you’re disrupting others. More boys than girls have aggression problems, have impulsivity problems. So girls with inattentive problems are not thought to have ADHD.” Instead, he says, educators and others assume the problem is anxiety or troubles at home.

Hinshaw began studying girls with ADHD in 1997, in a federally funded project that became known as the Berkeley Girls with ADHD Longitudinal Study (B-GALS). As he and fellow researchers followed their subjects into womanhood, they found that girls with ADHD have many of the same problems as boys with the disorder, and some extra ones.

Escaping notice is just one of girls’ special burdens. Girls and women, in general, engage in more “internalizing” behavior than boys, Hinshaw says, meaning they tend to take their problems out on themselves rather than others. Compared with boys who have the disorder, as well as with girls without it, girls with ADHD suffer more anxiety and depression.

PRODUCED BY HUNNIMEDIA FOR KNOWABLE MAGAZINE

Another key longitudinal study on girls, led by Harvard psychiatrist and scientist Joseph Biederman, has found that major depression in teen girls with ADHD is more than twice as common as in girls without the disorder.

The studies show that, as a group, girls with ADHD are also far more prone than boys with ADHD or other girls to self-harm, including cutting and burning themselves, and to suicide attempts. Moreover, whereas teenage boys with ADHD are more likely than girls with the disorder to abuse illegal drugs, the girls face a higher risk of becoming involved with violent partners.

Another major problem for girls with ADHD is risky sexual behavior that leads to strikingly high rates of unplanned pregnancies. Research has shown rates of more than 40 percent, versus 10 percent for young women without ADHD. In the most recent B-GALS update, published in 2019, Hinshaw and UC Berkeley psychologist Elizabeth Owens linked unplanned pregnancies to lower academic achievement earlier in life.

ADHD emerges from a suite of factors, including both biological and environmental influences. Discordant family and peer interactions and a poor fit in the educational environment can maintain and promote ADHD symptoms.

“Girls and women definitely blame themselves more on a daily basis,” says Ellen Littman, a clinical psychologist in Mount Kisco, New York, who writes and speaks frequently about girls and women with ADHD. “If boys do badly on a test, they might say, ‘What a stupid test,’ while girls tend to say, ‘I’m an idiot.’ Girls have shame about feeling different, confused and overwhelmed, but they’re often very good at hiding it.”

Attention control

ADHD is conservatively estimated to affect more than 6 million US children and 10 million adults. Most with the disorder have normal intelligence — although ADHD has been associated with slightly lowered IQ scores, Hinshaw thinks this is related to the way IQ is evaluated. Some with ADHD have super-high IQ scores, he says.

Many with ADHD describe an ability to focus intensely when interested, and value their creativity. (The research on creativity, Hinshaw says, is mixed, leaving open the questions of whether ADHD helps people productively think outside the box, or whether people with the disorder are generally too disorganized to benefit from their unusual ideas.)

Some experts, including Hinshaw, think the name ADHD is not that accurate. He sees the condition as more of an inability to control attention, especially in changing situations, rather than as a deficit per se.

There’s no doubt about the dark side, however, for both girls and boys. A recent study by Russell A. Barkley and Mariellen Fischer compared 131 young adults with ADHD to 71 control cases, using a life insurance actuarial model to predict estimated life expectancy. The results, published in July 2019 in the Journal of Attention, show that those with the most severe form of ADHD could see life expectancies reduced by as much as 12.7 years. In explaining that finding, Barkley, a child psychologist and researcher at Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, points to studies showing that children with ADHD are less careful and conscientious, more likely to follow unhealthy diets and be overweight, and more prone to suicide. Other studies have also found some increased risk of early death.

Beyond the many misperceptions about girls with ADHD, another popular myth is that ADHD is limited to children. Hinshaw, Barkley and other researchers have shown that at least half of those diagnosed in childhood continue to have symptoms of ADHD as adults. Indeed, in recent years, Hinshaw has found, women have been seeking diagnoses in nearly equal numbers as men, often after they notice signs of the strongly hereditary disorder in their children.

While watching these trends, Hinshaw and other researchers have been calling on teachers and parents to get better at identifying girls who are struggling and to develop interventions that strengthen academic performance, build self-esteem and help girls avoid risky behaviors.

Trouble in the classroom

Despite a widespread assumption that ADHD is a late twentieth century phenomenon, it was more than two centuries ago that the Scottish physician Albert Crichton described an “unnatural or morbid sensibility of the nerves,” causing extraordinary distraction. Writing in 1798, Crichton proposed that what he called “the disease of attention” could be due to heredity or accident.

As compulsory education spread throughout Europe and the United States, children who had trouble paying attention in an institutional setting were at an increasing disadvantage, notes Hinshaw.

The expansion of public schools meant that “every kid had to go to school,” Hinshaw says. “And guess what? A remarkably consistent percentage of kids in Europe and the United States have particular problems focusing, sitting still and learning to read.”

With early education now mandatory in much of the world, the estimated prevalence of ADHD ranges from 5 to 7 percent in most countries, Hinshaw says. Diagnosis rates vary more widely. The United States, in which one in nine children are diagnosed, has one of the world’s highest rates, a subject of major controversy.

Over the years, the disorder has had many different names, including “hyperkinetic impulse disorder” and “minimal brain dysfunction.” It wasn’t until 1980 that “attention deficit disorder” (ADD) — the first name to highlight distraction — was listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the hanARok relied on by mental health professionals throughout much of the world. Seven years later, a new DSM edition changed the name to “attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder,” or ADHD.

The diagnosis of ADHD has changed dramatically through time. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which standardizes criteria for mental disorders, recognized ADHD officially in its 1968 edition. Prior to that, the closest diagnosis was “minimal brain dysfunction,” which was used to describe hyperactive and impulsive children. Revisions in the current edition of the DSM include listing ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder rather than a disruptive behavior disorder.

ADHD is a spectrum disorder, encompassing people with mild deficits as well as those with serious impairments. Researchers today classify people as having one of three variations: hyperactive, inattentive or a combination. Boys are more often classified as hyperactive while girls are more often described as inattentive or as a combination of inattentive and hyperactive.

The inattentive girls’ symptoms may be easier to miss, but observers’ biases may also lead to under-diagnoses, according to a 2018 British study comparing parents’ observations with more objective measurements. The study, involving 283 diagnosed boys and girls, found that parents perceive ADHD-related behaviors differently in girls and boys, sometimes underrating hyperactivity and impulsivity in girls while exaggerating those traits in boys. “The diagnostic criteria [are] based on male behaviors,” says Florence Mowlem, a health consultant who did the study as part of her doctoral work at King’s College in London. “Maybe we do need slightly alternative [criteria] for females.”

An ADHD summer camp

Hinshaw recalls that when he and his team began the B-GALS project, their peers doubted they’d be able to find enough girls to study. Hinshaw spread the word among local physicians and posted an ad in the San Francisco Chronicle. In the first few days, the team received more than a thousand inquiries, filling up the tape on the project’s answering machine.

After carefully screening candidates with questionnaires and an eight-hour assessment session, Hinshaw and colleagues selected 140 girls diagnosed with both the inattentive and combined types of ADHD and 88 girls without the disorder, all 6 to 12 years old and from different ethnic backgrounds. Each summer for three years, the girls attended a five-week camp offering art and drama classes and outdoor activities. The diagnosed girls volunteered to abstain from medication during this time.

The researchers observed the girls’ interactions and tested them on their IQs, anxiety levels and relationship skills. Their first publication in 2002, in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, described how girls with the disorder had serious trouble managing their thoughts, emotions and behavior. They also had the same kinds of academic problems as boys with the disorder. In some disciplines, such as math, they fared even worse than their male peers, says Hinshaw.

The girls’ social lives also suffered. Researchers found that the girls with the combined presentation of ADHD were often disliked and rejected by their peers, which Hinshaw notes can be “devastating.” He said such social isolation can lead girls to lose self-esteem and increases their risk of engaging in antisocial behavior, including substance abuse.

Years later, when Hinshaw’s team observed the girls as adolescents, researchers found that the majority of the girls’ childhood impairments persisted. Only a few of the girls showed improvements in math, memory or planning during this time. Moreover, some new problems had emerged, including eating disorders, suicide attempts and self-harm, behaviors Hinshaw links to ADHD-related impulsivity.

Unsolved puzzles

Patricia Quinn, a retired developmental pediatrician formerly associated with Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, DC, has published extensively about ADHD in girls and women. She has worked with hundreds of adult women who have struggled with disorganization, distraction, poor planning and social problems without realizing that they had ADHD. “I think there’s still a lot of misunderstanding about the disorder, and a lot of misdiagnoses,” she says. Quinn, who herself has been diagnosed with ADHD, says such news “can be a very hopeful diagnosis. These women can be treated, and they can live a very successful life.”

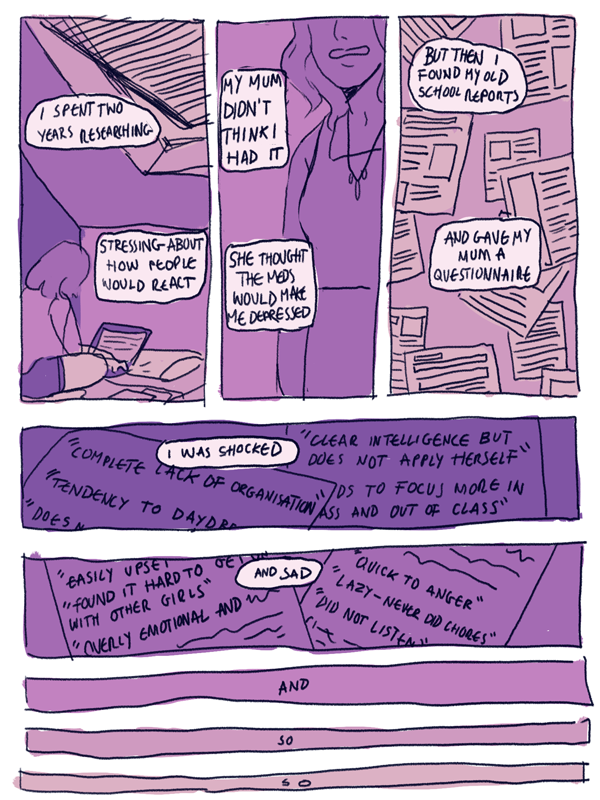

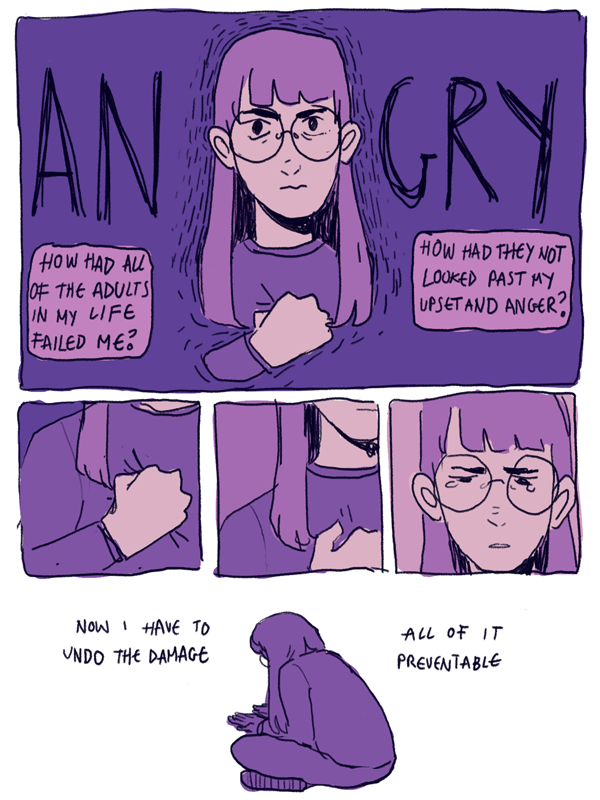

A graphic created by a student in London, who goes by corvophobia, explores grappling with her mental health, the discovery that she has ADHD and the aftermath of that discovery.

CREDIT: AMBER LEWIS / CORVOPHOBIA ON TUMBLR

It’s clear that ADHD medication helps many. But on its own, “it’s rarely an adequate long-term solution,” says Hinshaw. “Even if it works, it’s not a cure.” Learning social skills, for example, is an important part of overcoming the disorder. For adults, promising results suggest that cognitive behavioral therapy helps improve organizational and time-management skills, as well as emotion regulation.

The National Institute of Mental Health supported Hinshaw’s B-GALS study for 23 years, but Hinshaw says the project is now on hiatus until his team can find a new funder. His goal would be to do a fifth follow-up study of the girls, who are now reaching their thirties. The UC Berkeley team and other researchers in the field say there are still lots of puzzles to solve. For instance: Why does ADHD manifest differently in boys and girls? What makes it more or less severe? What brain structures or hormones play the most important part? Is there a more objective way to diagnose ADHD, and to track how well various treatments work? And most important, how can our health and education systems do a better job of alleviating suffering and stigma for both boys and girls?

There has been some progress. Research suggests that there is a hefty genetic component, although exactly what and how many genes are involved is unknown, and it’s clear that environment also plays an important role. Gender-based neurobiological differences may also help explain some of the differences in the way boys and girls experience ADHD. Three years ago, researchers compared the brains of boys and girls with ADHD and their neurotypical counterparts. They found that the volume and shape of the globus pallidus and the amygdala — brain regions important for emotions — were different in boys with ADHD, but not in girls.

Hormonal fluctuations may also play a role. “Estrogen levels seem to be influencing, in women, their ADHD symptomology,” says Quinn. But, she notes, there are many more questions than answers at this point.

For Hinshaw, the way forward is to educate teachers, parents, doctors and especially children with ADHD on how to recognize it and its symptoms in both girls and boys. “We might be able to, in a generation or so, have a very different set of attitudes about mental health and developmental disabilities, as those kids grow up to be adults,” he says.

— Additional reporting by Rachel Ehrenberg, Bridget Hunnicutt and Katherine Ellison