Adolescence is often portrayed as a period of struggle and friction, filled to the brim with exhilarating ups and depressing downs. Young people’s behavior tends to be stereotyped as self-absorbed and impulsive. But how accurate is this picture, and what might explain it?

Developmental neuroscientist Eveline Crone, based at Erasmus University Rotterdam, has studied adolescents, defined by researchers as people aged 10 to 24, for more than 20 years. She has gradually expanded her interest from the study of the many changes happening in adolescent brains to include her study subjects’ own views and experiences. This has helped to enrich her earlier findings on how young brains learn, produce emotions, process rewards and account for the perspectives of other people. It also provides new inspiration for adults trying to help them.

To study adolescents, Crone visualizes their brain activity while they are engaged in various tasks and games on computer screens: ones designed to assess behaviors and attitudes toward things like risk and reward, how they think about and are influenced by others, and more. She supplements these studies with other methods such as surveys and youth panels — and, these days, consults young people for their input from the moment the study is designed.

In an article in the 2020 Annual Review of Psychology, Crone and her colleague Andrew Fuligni of the University of California, Los Angeles, explore how adolescents feel and think about themselves and others, and stress that far from being either/or, both are inextricably intertwined. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get interested in studying adolescents, and how have your views evolved over time?

When I started to study psychology, I was interested in the way people think and make decisions, and I started to realize that you can answer these questions if you understand how they got there. That is how I got interested in development: I wanted to understand the pathways to becoming an adult.

Nowadays, I am much more interested in adolescence because of the promise of a new generation — I find it intriguing how every new generation of adolescents reinvents itself and society. Initially, my participants were really my subject, something I studied to understand the mechanism, but that has completely changed. From what I’ve learned, I feel I’ve become an advocate for young people.

When you started your research career, your own adolescence was a recent memory. Now it is rather more distant. How do you think that has affected your views on this phase of life?

We know from history that there has always been this view of adolescents as troublemakers. I am at an age now where I really start to see the differences between generations, and I do sometimes find myself rolling my eyes as well. But then I catch myself and think: OK, this is just how young people think or respond.

A recent example during the pandemic was that students would never put on their cameras when I was teaching. That was not nice for me, but then I have had to rethink and remind myself of research by Harvard psychologist Leah Somerville showing that in mid-adolescence, people are more embarrassed when they have to look at themselves on a screen, or if they have the idea that others are looking at them. So there are explanations for how they behave.

But — and this is what I also tell people when I give talks for a general audience — it may be good to know that some patterns of behavior are the same for everybody. Still, I’m not saying that means adolescence is easy, either for adolescents or parents!

Many people have found themselves wondering what is going on in adolescent brains. But how do you actually study it?

I originally trained as an experimental psychologist, so I was trained to develop experimental approaches that tap into certain mental processes. We ask people of various ages to perform a certain task — they respond to questions presented on a screen — and, using a brain imaging tool called fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging), we can look at activity patterns in the brain.

For example, you could think of a task where you make a choice alone or while friends are watching you, and we can look at the patterns of activity in the brain during each scenario and compare them. Using such an approach, we have explored a range of behaviors and responses — what happens when adolescents have to wait before receiving a reward, are thinking about themselves or others, or deciding whether or not cooperate, share with or give to others.

Because our experiments are designed to investigate very specific behaviors, it becomes less realistic, but it allows us to disentangle particular processes. Then we try to understand the same process by using surveys, talking to youth panels and using interventions to see if we can change a behavior. The idea is that if you approach the question in all these different ways, the advantages of one method compensate for the disadvantages of another.

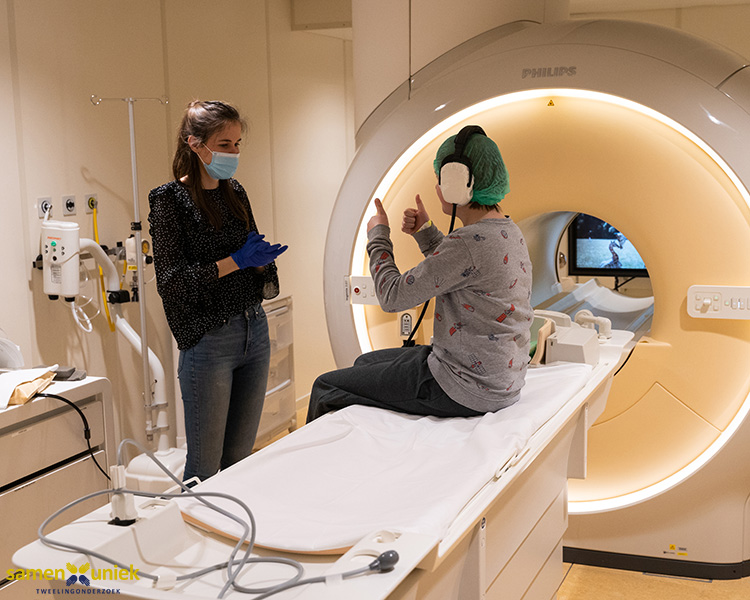

PhD student Simone Dobbelaar talks with an adolescent about to go into the MRI scanner. In psychological experiments, the scanner images their brain while they perform a series of tasks.

CREDITS: LEIDEN CONSORTIUM ON INDIVIDUAL DEVELOPMENT

Which brain regions have been found to change in adolescence, and what is the result?

I have always been intrigued by the prefrontal cortex, one of the latest brain regions to evolve as well as one of the last to develop as we grow up. It is important for rational thought, working memory, future planning and reasoning. Studying this region for more than 20 years using fMRI brain scans, we’ve observed that the maturation of the prefrontal cortex underlies key cognitive milestones that are important for reasoning.

Reasoning develops while we are growing up. Young children are a bit more focused on explorative trial-and-error learning. But the older we get, the more we consider strategic motives, and think about the consequences of our actions for ourselves and others, now and in the future. We rely more on cognitive strategies; we are far more inclined to rationalize — we can’t even control it. The primary emotions speak less, because adults more easily control their emotions.

Our team has studied the role of a certain reward region in the brain, the ventral striatum, in relation to risk-taking behavior, often using an online gambling task in which participants could win or lose money for themselves, their best friend or a disliked person. While only a small percentage of adolescents gets in trouble through extreme risk-taking, we see that the ventral striatum becomes more active for all adolescents when a risky choice — for example, a risky bet that will yield a lot of money if they win — results in rewards for themselves, or when risky choices are made in the presence of friends.

We also discovered that this response is seen for rewards that benefit their friends, their parents or other people that are close to them, suggesting adolescents are also sensitive to benefits for others.

The activity of these regions peaks in mid-adolescence and decreases when we get older. But that finding is very sensitive to how we design the experiment, so it is not always found. To me, that is a supercool scientific puzzle: Why is it that sometimes, adolescents do not show this peak in sensitivity to things that are rewarding, whether it’s risk-taking or helping others? I like variance, because it suggests you can make changes to give young people the opportunity to grow up successfully. Adolescence may be a time in life when social experiences really matter and have long-lasting effects on people’s kindness and how they feel connected to others.

An overview of the main brain regions involved in thinking about ourselves and others.

To many people, adolescent behavior seems unnecessarily impulsive. Do you think this has an important function, or could it be simply a side effect of some necessary steps in brain development?

Usually, I think this is beneficial to young people. It can really help adolescents to go out there and seek new experiences. It’s a huge transition from being a child and being totally dependent on your parents, to all of a sudden distancing yourself from the rules of the house to find your way out there. There must be a kind of trigger for that. But of course, some risk-taking is too dangerous, and that, I think, is a side effect of the helpful, adaptive function of risk-taking that propels teens into adulthood.

In your review, you focus on the parts of the brain that allow us to think about ourselves and others. It turns out these are largely the same ones — was this a surprise to you?

The social brain network, four regions in the brain that are consistently active when you think of social situations, is very robustly found across hundreds of studies. One of these areas, the medial prefrontal cortex, is also strongly engaged when you think about yourself, so this region appears to be involved in both.

We really expected that self- and other-processing could be separated. But it turned out that every time, the same region of the brain was activated whether adolescents got an assignment to think about their own traits, to think about others or to think about what other people think of them — it was the same area over and over again.

Now I don’t think that they can be disentangled anymore. You constantly reflect on yourself when you interact with others, and when you interact with others, it has an effect on how you feel about yourself.

The medial prefrontal cortex is more active in adolescents than in adults, and some studies even show a peak in activity. The big question is why. We think it might reflect an increased use of strategizing which, as I’ve explained, the prefrontal cortex is involved in. But it’s also possible that there is more introspection, that adolescents spend more time thinking about themselves.

Another brain area that is part of the social brain network, the temporoparietal junction, specifically becomes active when you switch your perspective between yourself and others. We did some research in adolescents with a history of delinquent behavior and found that the temporoparietal junction showed less variation in activity across different social situations in adolescents with a history of delinquency, compared with others. One potential explanation is that they are not as successful in switching from their own perspective to others’. But there are many other reasons this could be, so it is good to be modest in this respect.

That, to me, was somehow a hopeful message: This is something we can possibly train people to be better at — you can learn to take the perspective of others. Well-adjusted people tend to do that automatically.

How might your research help us to reduce frictions between adolescents and adults?

My research has made me rethink the assumption of adolescents being troublemakers, because it just didn’t fit the data. We have demonstrated such a strong feeling of purpose and meaning in adolescents. They feel a fundamental need to contribute in a positive way.

I no longer think it should be our goal to always have complete understanding between generations. I don’t think it’s possible. And I think that’s a good thing. Historically, we have seen many examples where the younger generation shapes society in ways that may not always align with the norms of previous generations. But this planet is theirs for the future, so they should have a say in what they find important.

The climate debate is a good example; young people have very different ideas about sustainability and take part in demonstrations for a healthier planet. I believe their voice is important here, even when it is uncomfortable for the older generations.

For interventions, research shows that ones thought up by adults to help adolescents often don’t work. Young people should have the space to develop new ideas and put them in practice themselves. That is something I have also learned over time — if adolescents can invent their own approach, it is much more likely to work.

So the question for adults is: How can we provide optimal opportunities for young people to develop and become socially engaged individuals? The way you do it is very important. You should engage young people when designing programs and take their opinions seriously.

Many adolescents are impatient for the world to become a better place, and eager to help make that happen. Developmental neuroscientist Evelyn Crone says that her studies on the adolescent brain have altered her own perspective: “We have demonstrated such a strong feeling of purpose and meaning in adolescents. They feel a fundamental need to contribute in a positive way.”

CREDIT: JULIAN MEEHAN / FLICKR

How might this research inspire parents, for whom this is often also a complicated time?

Research has shown that being too strict or too loose is not helpful. Adolescents need guidance as well as opportunities to explore. That is not my own research, but I think it makes a lot of sense. The important thing is that we know from brain imaging that brain activity can change, and that it matters what you do as parents. Because the brain is especially plastic in adolescence, there is a window of opportunity to provide support and help adolescents grow into the best versions of themselves. Young people still find the opinions of their parents very important.

How do adolescents themselves tend to respond to your research, and how might it help them?

Young people are intrigued by seeing the brain in action — it makes them excited about science. But it depends on what story you tell: When you say to adolescents that their brains are more receptive to risk-taking, that might become a self-fulfilling prophecy. But I always hope that with my work, they’ll feel empowered.

It’s good to understand where your emotions or thoughts are coming from, to know that you can use this period to find out who you are, and that it’s OK if this takes time and if it’s difficult sometimes. If you know that this is a time of larger fluctuations in mood, it can help you to understand that this is part of growing up, that it can be useful, and that it will get better.

We’ve followed adolescents during the pandemic, and we see that negative feelings kept increasing, even when regulations were loosened, and positive feelings kept decreasing. One explanation was that they couldn’t imagine their futures — having a dot on the horizon and knowing where you are going — because everything was so unpredictable, no one knew how long the pandemic would last. Some have suffered immensely.

Adolescents made a big sacrifice to help the older generations, and I think for a good reason. But I do believe that when we get older, we don’t remember just how important that time of your life is — how it may impact how you’ll live your life, how you feel connected to other people and whether you feel the government is there for you. During the pandemic and the resulting restrictions, many young people felt they were not being taken seriously.

If they say that they find it important to have a safe space to talk about their mental health, we should support that. I hope my research will help adults to see the opportunities of adolescence. Young people are the future — we should invest in them, to help them to become caring and responsible citizens.