If the cascading upheavals of the past year have done nothing else, they’ve spurred widespread calls for reform and renewal in just about every institution we have.

A mishandled public-health response to the Covid-19 pandemic, an economic crisis, a racial reckoning, an uncommonly long string of hurricanes, wildfires and other climate-enhanced disasters — almost everything that’s happened in these tumultuous months grew out of problems that had been swept under the rug for decades, says Anita Chandra, who directs the social and economic well-being program at the RAND Corporation. “The issues around police-related violence and systemic racism were brewing,” she says. “The issues around sustainability were brewing. The widening income inequality gap was not just brewing, it was full throttle.”

The good news is that the new US administration has been trying to address these issues in a systematic way — although with results that remain to be seen, given the partisan gridlock that still prevails in Washington and elsewhere. But perhaps more heartening are the many new tools and approaches that reformers have to work with. Since at least the mid-1990s, scholars and policy makers around the world have been exploring a series of innovations that amount to a radical rethinking of the machinery of government.

It would be too much to claim that their work amounts to an organized movement. A partial list of their proposed solutions would include terms like public value, the enabling state, the well-being economy, co-governing, or — because many of the innovations are being explored at the local level — the new urban governance. But their efforts do tend to share a number of broad goals.

One goal is to foster long-term, integrated thinking across agencies, regions and different levels of government — and hopefully help officials get out in front of brewing problems before they become crises. Another is to help governments become much more responsive and evidence-driven when it comes to meeting people’s real-world needs. And still another is to make governments far more participatory and inclusive than most have been in the past.

These experiments are still works in progress. But here are some examples that give us a glimpse of what the post-pandemic world could look like.

Long-term, integrated thinking: Urban sustainability plans

After a year like the one we’ve all just been through, one conclusion seems obvious: Governments at every level need to get much, much better at practicing the policy equivalent of preventative medicine, by grappling with problems while they’re still manageable instead of waiting until they require a societal 911.

Several of the innovations try to help. One is agent-based modeling, an advanced simulation technique that researchers can use to create, monitor and experiment upon entire artificial societies running inside a computer. When calibrated with real-world data, these models can serve as an effective early warning system for festering problems. They can also find use as a test bed for potential solutions and a guide for sidestepping unintended consequences — all of which is why the models are increasingly being used for transportation planning, pandemic preparedness and economic forecasts.

But on the low-tech side, mayors around the world have also been getting a surprising amount of leverage from their local sustainability plans — wide-ranging policy blueprints that have now been adopted in hundreds, if not thousands, of cities worldwide.

The very act of creating these plans puts people into a strategic mindset, explains Mark Gold, an environmental scientist who headed the Sustainable LA Grand Challenge at the University of California, Los Angeles until 2019, and who is now the state’s deputy secretary for Oceans and Coastal Policy. “You can ensure that different programs and policies are integrated across the board,” he says, “and that the glaring gaps that a typical city would not be able to deal with get filled in, because you’re looking at a holistic perspective.”

And the reason this works is that the concept of sustainability is much broader that most people realize. When they hear the word “sustainability,” says Alicia Harley, a sustainability scholar at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, “oftentimes people think, ‘OK, that means “environment,”’ so they must just be talking about climate change, and maybe saving the ocean.”

But as she and the Kennedy School’s William Clark pointed out in the 2020 Annual Review of Environment and Resources, sustainability actually encompasses every aspect of human well-being and equity. Or as Clark puts it, sustainability is about living well today, “but in ways that don’t undermine your neighbor’s ability to improve their well-being because you’re dumping garbage in their backyard, or future generations’ ability because you’re stealing all their resources.”

This expansive definition of sustainability came to the fore in the late 1980s, notably in the landmark United Nations’ 1987 report on environment and development, Our Common Future. The report explicitly tied economic prosperity and human well-being to environmental health — a “triple bottom line” that’s often summarized as “people, planet, profit.” The three can’t be separated, the report emphasized: “A world in which poverty and inequity are endemic will always be prone to ecological and other crises.”

The modern concept of sustainability gives human well-being and economic prosperity equal weight to the environment.

This kind of comprehensive, triple–bottom-line sensibility eventually found a receptive audience in city halls around the world — especially in the 2000s, as climate change became harder and harder to ignore.

Whatever a mayor’s personal politics on the subject, “the effects of climate change are coming home to roost for cities — they’re dealing with drought, wildfire, flooding basements,” says Alaina Harkness, who deals with water issues as executive director of the Chicago-based nonprofit Current. “Cities just have the pragmatic reality on their front door step every single day.”

Worse, these climate-enhanced disasters were coming as cities continued to struggle with all-too-familiar issues like crumbling infrastructure, manufacturing plant closures and the human costs of inequality, racism, poverty and pollution — systemic problems that simply cannot be solved one by one. So, what Gold calls “the overarching umbrella of a sustainable city plan” proved to be a handy way for mayors to tackle all these problems at once.

“A world in which poverty and inequity are endemic will always be prone to ecological and other crises.”

Our Common Future, UN ReportMany of them already had environmental plans to build upon. As early as 1989, for example, Irvine, California, had reacted to the slow pace of international ozone-layer protections by passing a law to restrict chlorofluorocarbon emissions in the city. And in September 1990, some 350 local officials from 43 nations had formed a mutual support group known as the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI). “Global problems” they declared, “require local solutions.”

By the 2000s and 2010s, these initiatives had begun to morph into comprehensive sustainability plans — some of which, in large cities such as New York, London and Copenhagen, became very ambitious indeed.

In 2019, for example, Los Angeles updated its four-year-old Sustainable City pLAn based on feasibility studies carried out by Gold’s UCLA team and others. Pointedly called “L.A.’s Green New Deal,” the new plan committed the city to recycling 100 percent of its wastewater by 2035, working toward 100 percent renewable electricity by 2045, making every home, store and office carbon-emissions–free by 2050 and creating 300,000 clean new jobs by 2035.

But just as often, the plans have incorporated comparatively simple, inexpensive measures that serve many goals simultaneously. While at Columbia University in New York, for example, civil engineer Patricia Culligan worked closely with the city to analyze its plan for “green infrastructure”: a network of leafy enclaves that range in size from portions of huge parks down to tiny rain gardens notched into public sidewalks.

These green spaces help absorb stormwater runoff before it swamps treatment plants and washes raw sewage into surrounding lakes and rivers, says Culligan, now at the University of Notre Dame. But they also provide shade to reduce summer temperatures and energy use, habitat for birds and other wildlife and an enhanced sense of well-being for people in the neighborhood. “These include places where people can sit, relax and walk their dogs,” she says.

A “Sponge park” (bottom) was added along the Gowanus Canal (top, before park was built) in Brooklyn, New York. Such green infrastructure can serve many sustainability goals at once, whether it’s providing a home for wildlife, enhancing visitors’ sense of well-being or absorbing stormwater before it washes sewage into the bay.

CREDIT: DLANDSTUDIO PLLC

Of course, that still leaves a lot of cities that are not addressing climate change, which is why national and international agreements remain necessary.

“There is this massive hope being placed onto cities that they’re going to save the world,” says Nuno F. da Cruz, who studies urban governance at the London School of Economics, “but they have not been given the power, the autonomy or the budget to do this.”

But that’s precisely why cities have spent the last decade and a half organizing to give themselves a global voice. A prime example is the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, which was founded in 2005 to coordinate climate activism among the world’s “megacities.” Today it comprises 97 large cities that collectively represent one in every 12 people in the planet and 25 percent of the globe’s economic output.

C40 was soon joined by a host of organizations pursuing similar goals — most of which are emblazoned in their names. The list includes Local Governments for Sustainability (the current name for ICLEI, now with more than 2,500 members worldwide), the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy (10,709 members), the Climate Mayors network (more than 470 US mayors), the Urban Sustainability Directors Network (more than 200 communities in North America), and the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance (22 cities worldwide).

With numbers like that, politicians are inclined to listen, says da Cruz. Witness the 2015 negotiations that led to the United Nations’ Paris Agreement on climate change — a promise from virtually every nation in the world to aggressively cut their greenhouse gas emissions. Mayors didn’t have a formal seat at the talks, since the United Nations has always been set up to work through member states. So instead, says Sheila Foster, who studies urban law and governance at Georgetown University, “mayors would meet right in the same city and put pressure on the nation-states to reach an agreement.”

Some 400 of them gathered in Paris as the pact was being finalized, in what was essentially a public declaration that global problems were no longer above cities’ pay grade — a sentiment underscored by the fact that the fraction of the human race living in cities passed 50 percent in 2007 and is headed beyond two-thirds by 2050. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon was supportive; once the deal was done he announced that in future UN negotiations, cities most definitely would have a seat at the table.

United Nations officials celebrating the adoption of the Paris Climate Accords in 2015. Cities from around the world organized themselves to have a say in the outcome.

CREDIT: ARNAUD BOUISSOU, COP PARIS / FLICKR

Responsive, evidence-driven action: Measuring what matters

“What gets measured, gets managed,” goes the old saying — or, as it’s sometimes expressed, “We measure what we value, and value what we measure.”

Either way, this thought captures the many concerns people have about that ubiquitous metric known as GDP, the gross domestic product. GDP is a fine measure of a country’s economic activity: It’s just the nation’s total output of goods and services over a given time period. As such, it’s been a fixture in policy-making circles since 1934, when its ancestor, the “national income,” was developed as a way for Congress to track the US economy’s recovery from the Great Depression. Today the GDP is used by the White House and Congress in preparing the federal budget (and seeking to score political points), by the Federal Reserve in setting monetary policy, by Wall Street, by businesses, by the World Bank — on and on.

Along the way, though, GDP has also become a widely used proxy for public well-being, health and a host of other noneconomic factors. And that’s the concern. Yes, a country’s GDP per capita does have a strong correlation with quality-of-life issues such as education levels, life expectancy and infant mortality. But, as critics have been pointing out since at least the 1970s, using GDP as the only measure of well-being can seriously distort the choice of what gets measured and managed.

GDP ignores anything that doesn’t generate money, like leisure time or relationships. It assigns a value of zero to the environment, while assigning a positive value to the billions of dollars spent on cleaning up, say, an oil spill. It celebrates economic growth in the here and now, while downplaying threats to future growth like climate change. And it reinforces the illusion that everyone is doing well when the GDP numbers are good — no matter what kinds of degradation or injustice people face on the ground.

The obvious solution is to supplement the economic numbers with good metrics for well-being, environmental health and all the rest. And plenty of people have tried. But as late as 1999, “our efforts to get alternative metrics were a total train wreck,” says Harvard’s Clark, who cochaired a report on sustainability science that year for the National Research Council. Not only was there no agreement at the time, he says, but also “everyone’s preferred set of metrics was completely ad hoc. It was just the five things they cared a lot about, while ignoring the 10 things they didn’t happen to care much about.”

Happily, says Clark, these efforts began to get much more comprehensive and rigorous in the 2000s. And then, he says, one of the big pushes was a blue-ribbon panel of 25 economists and behavioral scientists that then-French President Nicolas Sarkozy commissioned in February 2008, when the world’s financial system was already collapsing toward the Great Recession. Sarkozy’s basic message to the group was that the world had walked itself into a trap by following GDP. Could they find a better way?

They could. Led by a trio of eminent economists that included two Nobel laureates, Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia and Amartya Sen of Harvard, as well as France’s Jean-Paul Fitoussi, the commissioners spent the next year and a half poring through decades of research on the metrics. And they came to two broad conclusions.

The first was that yes, it was time to start measuring human well-being directly. This was admittedly tricky, given that well-being is a complex, multifaceted, know-it-when-you-see-it quality that’s impossible to capture in a single number. But a growing body of research had greatly clarified the issue. For example, many studies showed that well-being is not just the subjective experience of happiness or satisfaction, although that is clearly a part of it.

Well-being also arises from the connections people feel with their families, friends and communities. And it is deeply intertwined with their sense of purpose, agency and opportunity — their pursuit of happiness, so to speak. “Just making sure people are fed and clothed and have a house is insufficient,” says Harvard’s Harley. In addition, she says, “people need the capacity to pursue their own vision of the good life.”

The commission was partially influenced by the capability approach that Sen had pioneered in the 1980s, and that had then been elaborated by philosopher Martha Nussbaum at the University of Chicago. The idea is that the right to vote, say, means little if people don’t have the relevant capabilities, like being able to register and get to the polls. Likewise for nutrition, which requires the capability to access quality foods; for health, which requires the capability to access medical care; for education; and for a long list of others. Poverty and oppression, in this view, are tantamount to capability deprivation.

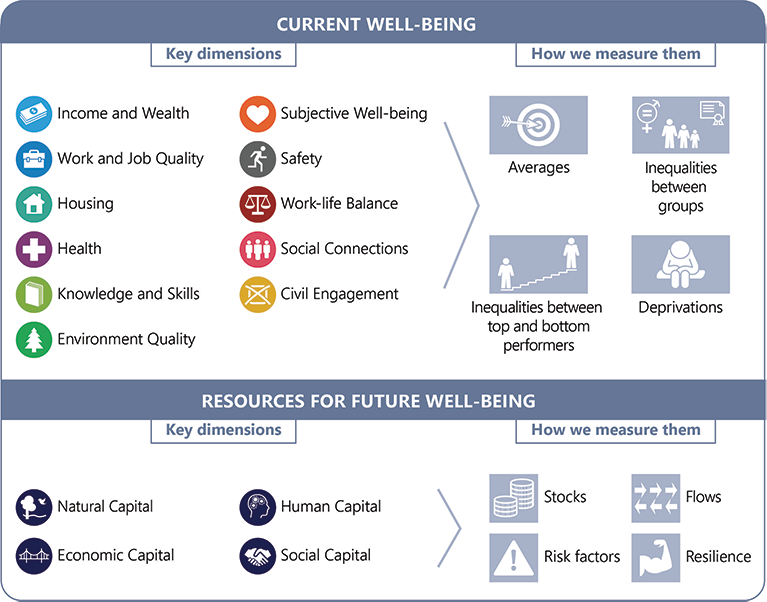

In the end, the commissioners used the research literature to identify at least eight dimensions of well-being: material living standards, health, education, work and personal activities, political voice, social connections, environment, and physical and economic security (or the lack of it). They also emphasized that each dimension has to be measured separately, using both objective and subjective data.

“Just making sure people are fed and clothed and have a house is insufficient. People need the capacity to pursue their own vision of the good life.”

Alicia HarleyBut the commission’s second major conclusion added an important caveat: We shouldn’t confuse measures of current well-being with measures of sustainability, which (in their definition) is our ability to maintain today’s levels of well-being into the future. For the latter task, said the commissioners, the right metrics are found in the “inclusive wealth” framework that had gained traction with the larger community only in the 2000s.

What inclusive wealth does, says Clark, is to take the classic economic concept of capital “and remorselessly expand that to include all the stocks of resources that you and I could call on to build our well-being.” Not everyone defines these stocks in the same way, but it’s common to list four: manufactured capital (money, infrastructure, buildings and machinery), human capital (experience, education and know-how), social capital (the institutions and relationships that keep society functioning) and natural capital (resources like oil or timber, plus ecosystem services such as flood control or pollination). The payoff is that the ebb and flow in each of these forms of capital can be quantified with hard data, allowing officials to monitor whether a given sector is moving in a sustainable direction or not.

When the commission released its final report in September 2009, its stellar authorship alone drew widespread attention. Besides, whatever Sarkozy’s later legal troubles — a French court convicted him of corruption in March 2021 — he was hardly alone in his disillusionment with GDP. If nothing else, having better metrics might give officials a little more warning before societal problems become crises — not to mention helping citizens hold their governments accountable for solutions.

In Paris, for example, the intergovernmental Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) began using a slightly expanded version of the commission's framework in 2011 to measure human well-being and progress in nations around the world. Both the World Bank and the United Nations are now gauging the sustainability of nations via the inclusive wealth approach. In March 2021, in fact, the UN Statistical Commission strongly endorsed the natural-capital measures of inclusive wealth as a way to quantify environmental issues.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is using a slightly expanded version of the Sarkozy commission’s metrics to measure well-being and sustainable development in nations around the world.

CREDIT: OECD (2020), “THE OECD WELL-BEING FRAMEWORK”, IN HOW'S LIFE? 2020: MEASURING WELL-BEING, OECD PUBLISHING, PARIS.

In 2018, meanwhile, Scotland, Iceland and New Zealand (later joined by Wales and Finland) formed Wellbeing Economy Governments, a coalition of national and regional authorities that pledge to recenter their economies around well-being. And a long list of other countries have begun to incorporate at least some consideration of well-being into their policy making.

But of course, says Stephen Polasky, an economist at the University of Minnesota who wrote about the inclusive wealth approach in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources, these measures by themselves are only the first step. “Being able to measure and count doesn’t mean that you’ve actually done anything on incentive” — getting those numbers into day-to-day decision making, he says.

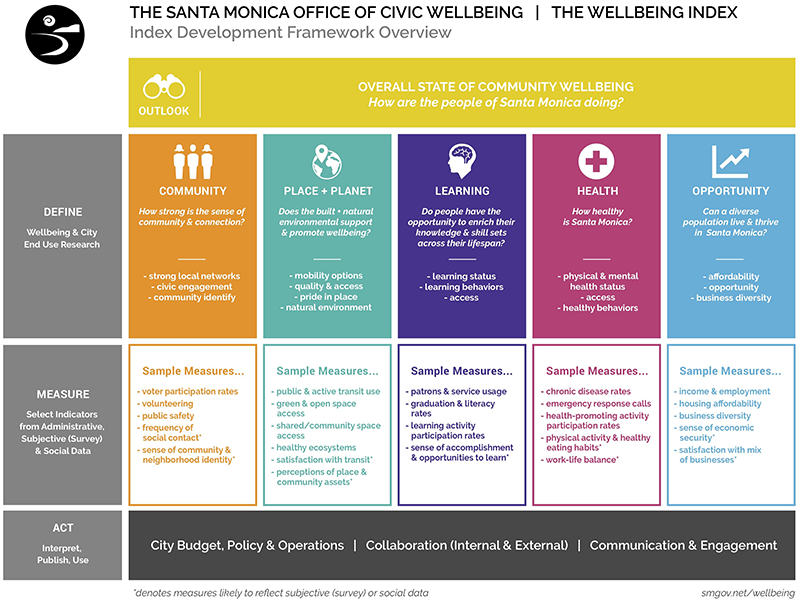

At least some cities have started taking the lead, by adapting these national-scale metrics into urban-scale frameworks that can map out problems and inequities all the way down to the neighborhood level. One closely watched example: Santa Monica’s well-being project, which was launched in 2014 using well-being metrics developed in collaboration with Chandra’s group at RAND and the New Economics Foundation in London, and informed in part by the OECD framework.

Cities such as Santa Monica, California, have begun to go beyond conventional economic measures of success, and are instead using multiple quantitative and subjective metrics to get a more complete picture of their citizens’ well-being.

CREDIT: santamonicawellbeing.org

“Our index uses data from three sources,” says Julie Rusk, who spearheaded the project as head of Santa Monica’s office of civic well-being. The first source is traditional, comprising hard-number data on population, unemployment, crime rates, graduation rates, tree canopy, voter rates and so on — the kind of administrative statistics that most cities collect as a matter of routine. The second is new to this project: a researcher-designed survey that tries to gauge respondents’ life satisfaction, sense of purpose and subjective well-being. And the third is experimental, including sentiment analysis, geographic location and other insights mined from social media. “It’s what the private sector does all the time for marketing,” says Rusk. “We’re using it for the public good.”

The index organizes these data around six dimensions of well-being: outlook (how people feel about their lives), community (how connected they are), place and planet (their environment), learning, health, and economic opportunity. And the findings, in turn, have informed priorities for budgets and policies in every city agency, with a special emphasis on racial equity. “Santa Monica really took it to the next level in terms of government use,” says Chandra.

Indeed, the metrics have continued to play that role even in the depths of the Covid-19 crisis, which forced the city to close Rusk’s well-being office last year in the face of massive budget shortfalls. She quickly reconstituted her group as a nonprofit, Civic Wellbeing Partners, that has continued to promote the office’s well-being framework, index findings and equity work while also helping other cities do what Santa Monica did.

“It’s clear to me that this work is going to continue,” says Rusk. “It is continuing in other places. We’re just figuring out exactly what form it will take once we get through this transition.”

Participatory, inclusive government: Citizens’ assemblies

US politics has been polarized and gridlocked for so long that for many people it’s come to seem like the natural order of things.

But then, Ireland seemed to be headed in that same direction a decade ago, when the Irish economy was still reeling from the Great Recession, the Irish public was feeling deeply mistrustful of its government, and the country’s 1937 constitution was in dire need of an update to the 21st century. The difference is that in 2012, the legislature in Dublin decided that it should try something that wasn’t just business as usual. It called a Convention on the Constitution to evaluate eight areas that were ripe for change — including the hot-button issue of same-sex marriage — but didn’t just fill the convention with the same old politicians. Two-thirds of the 100-member group would consist of ordinary citizens selected at random.

Ireland’s inspiration for this move was the citizens’ assembly, a structure that British Columbia pioneered in 2004 when voters in the Canadian province demanded electoral reform. (The assembly ended up recommending a variant on ranked-choice voting that narrowly missed being approved by referendum in 2005.) But British Columbia’s idea was itself inspired by earlier experiments in participatory democracy. Among its many antecedents were consensus conferences, first used in the 1960s to give citizens a chance to publicly question experts on biomedical technologies; citizens’ juries, developed in the 1970s to allow nonpoliticians to weigh in on policy issues; and Deliberative Polling, the trademarked name for a technique developed in the 1980s to foster informed, engaged policy debate among hundreds of citizens at a time.

These deliberative-democracy mechanisms and their relatives vary considerably in terms of size, cost and time frame, says Simone Chambers, a political scientist at the University of California, Irvine, who surveyed this movement for the 2003 Annual Review of Political Science. But what they share is a goal — giving the public a voice that goes beyond voting every few years — and an approach.

Citizens’ assemblies, like this one in Birmingham, England, held in January 2020, ask ordinary people to grapple with controversial issues such as climate change.

CREDIT: PA IMAGES / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

First, says Chambers, “a defining characteristic is that citizens are chosen by lot.” Typically, in fact, they’re chosen with a statistical distribution of gender, ethnicity, political affiliation and so on that matches the populace at large. If the group is large enough, this can ensure that the discussions represent the entire range of public opinion — and, not incidentally, can keep the debate from being taken over by officials who are pushing their own agenda, or the kind of self-selected activists who dominate conventional politics.

Next, however, the citizen-participants aren’t just asked to give opinions on topics they’ve barely thought about, which is what tends to happen in standard polls. Instead, they are allowed plenty of time to educate themselves — complete with data, explanatory readings and Q&A sessions with experts in the field.

And finally, the participants break out into small face-to-face groups that try to reach mutual understanding and at least some agreement on ways to move forward. It’s deliberation, not a debate, says John Dryzek, a political scientist at the University of Canberra who has written extensively about deliberative democracy (including in the 2012 Annual Review of Political Science). “In a debate, you’re trying to score points off the other side,” he says. “In a deliberation, it’s much more oriented to mutual understanding, communicating in ways that can reach people who might be from a different ideology, a different religious background, a different nationality — who do not have the same starting point as you do.”

Although there are many variations on deliberative democracy, the basic idea is the same: Choose a representative sample of citizens, ask them to tackle a knotty public issue like abortion or same-sex marriage, give them time to deliberate among themselves and query experts, and then ask them to produce an informed opinion.

Having observed lots of these events, adds Dryzek, he finds it striking that the citizen-participants are actually quite good at this kind of reach-across-the-divide deliberation — and at seeing right through BS. “They know when they’re being fooled” by advocates on one side or another, he says, “and they can make good judgments about what sorts of arguments stand up, and what sorts of arguments don’t.”

“We have good empirical evidence that citizens do a really amazing job when they’re given enough time and information,” agrees Chambers. Furthermore, she says, there is evidence that the public at large tends to trust the conclusions of a citizens’ assembly much more than the information they get from partisans on either side.

Certainly that was the case in Ireland. The Convention on the Constitution met on 10 weekends spaced out from December 2012 through March 2014, earning high marks for its transparency. Its meetings were live-streamed, and garnered news coverage that sparked national debate. The convention ended up sending evaluations to the legislature on each of the eight proposed amendments — including a strong recommendation by 79 percent of participants to allow same-sex marriage. The legislature accordingly put the amendment to a national referendum; it passed in May 2015.

The participants also recommended unanimously that there be a second convention. The Irish Citizens’ Assembly duly met over 12 weekends between 2016 and 2018 (this time without politician-members) and tackled several other contested issues — of which by far the most sensitive in that heavily Catholic country was the move to repeal amendment eight, which effectively banned abortion. As with same-sex marriage, says Dryzek, the Church was strongly opposed to reform. “These had been regarded as issues that government shouldn’t touch,” he says. But the citizens’ assembly recommended repeal, which seemed to have a strong effect on public opinion. The government put the repeal to a referendum — which resoundingly passed in May 2018.

The success of that process was an amazing result all by itself, says Chambers. “The outcomes of the citizen assembly produced this national conversation that wasn’t all that polarized,” she says, “even though the questions on the ballots were gay marriage and abortion.”

But more than that, says Dryzek, the convention and assembly process improved the quality of deliberation throughout the political system. “It was a way of ensuring that good arguments are sorted from the bad ones,” he says, “and that the good arguments then prevailed in government more broadly.” Indeed, he adds, citizens’ assemblies have become a part of the accepted political landscape in Ireland. In 2019, the country decided to examine issues of gender equity with a new assembly, which delivered its recommendations in April 2021.

So — do Ireland’s constitutional convention and citizens’ assembly provide an example for others to follow as we recover from the tumult of 2020?

Maybe. Although the Irish experience is often cited as the most successful example of participatory democracy to date, it also showed why these events can be tough to pull off. One challenge is retention: Ireland asked participants to serve multiple weekends without pay, or — in the case of the Constitutional Convention — without even childcare costs. Just 61 out of the 99 original participants in Ireland’s citizens’ assembly remained after all 12 meetings. The obvious solution is to pay the participants, but that gets expensive.

Another challenge is to ensure that the selection of participants is really random. The citizens’ assembly had to dismiss seven replacement members in early 2018 after it was discovered that one of the recruiters had simply been calling up friends. Still another is to keep the powers that be from manipulating the results by, say, providing the assembly with a slanted group of experts. That wasn’t a problem in Ireland, says Dryzek, but it is why some assemblies are given the power to call any experts they want.

And finally, of course, there is the eternal challenge of getting governments to listen. Although the same-sex marriage and abortion amendments were put to a vote in Ireland, many of the groups’ other recommendations went nowhere.

Yet none of these challenges have stopped people from trying, says Dryzek. The movement for deliberative innovations has exploded, especially over the last decade or so. In 2019, for example, Scotland convened a citizens’ assembly to discuss issues such as Brexit and, starting last year, the region’s response to Covid-19. The German-speaking region of Belgium has created a citizens’ assembly to be a permanent part of its government. Oregon has taken to convening a 24-member Citizens’ Initiative Review to evaluate proposed ballot measures; prior to the election, the state then includes the panel’s report in each voter’s information packet. The Latinno project has compiled a comprehensive database of hundreds of participatory projects across 18 countries in Latin America. The OECD has synthesized best practices for these efforts.

The numbers are growing so fast that it’s hard to keep count, says Dryzek: “I’m continually surprised to find that something has happened in a country that I knew nothing about.”

Of course, it could easily be a decade or more before we know whether any of the fixes described here can really make a difference. But if nothing else, they remind us that there are other ways to do things. That we’re not doomed to endlessly keep slamming our heads against the same proverbial stone walls. That fundamental resets are possible — and that maybe, just maybe, the shock of the pandemic year will goad us into trying.

This article is part of Reset: The Science of Crisis & Recovery, an ongoing Knowable Magazine series exploring how the world is navigating the coronavirus pandemic, its consequences and the way forward. Reset is supported by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.