Most languages develop through centuries of use among groups of people. But some have a different origin: They are invented, from scratch, from one individual’s mind. Familiar examples include the international language Esperanto, the Klingon language from “Star Trek” and the Elvish tongues from “The Lord of the Rings.”

The activity isn’t new — the earliest recorded invented language was by medieval nun Hildegard von Bingen — but the Internet now allows much wider sharing of such languages among the small communities of people who speak and create them.

Christine Schreyer, a linguistic anthropologist at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus in Kelowna, Canada, has studied invented languages and the people who speak them, a topic she writes about in the 2021 Annual Review of Anthropology. But Schreyer brings another skill to the table: She’s a language creator herself and has invented several languages for the movie industry: the Kryptonian language for “Man of Steel,” Eltarian for “Power Rangers,” Beama (Cro-Magnon) for “Alpha” and Atlantean for “Zack Snyder’s Justice League.”

Schreyer spoke with Knowable Magazine about her experience in this unusual world, and the practical lessons that it provides for people trying to revitalize endangered natural languages. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you come to study something as esoteric as invented languages?

I teach a course on linguistic anthropology, in which I give my students the task of creating new languages as they learn about the parts of languages. Around the time I started doing that, “Avatar” came out. The Na’vi language from that movie was very popular at the time and had made its way into many news stories about people learning the language — and doing it quickly.

My other academic research is on language revitalization, with indigenous or minority communities. One of the challenges we have is it takes people a long time to learn a language. I was interested to know what endangered-language communities could learn from these created-language fan communities, to learn languages faster. I wanted to discover who the speakers of Na’vi were, and why and how they were learning this particular created language.

In this five-minute video, a linguist explains how invented languages show the characteristics of real languages.

CREDIT: LESSON BY JOHN McWHORTER, ANIMATION BY ENJOYANIMATION

And?

When I surveyed Na’vi speakers, many said they joined because they were fans of the film and they stayed for the community. They’re very welcoming and inclusive communities. It doesn’t matter what your race is or what your gender is, though many of these fandoms tend to be more male.

But also, one of the things I saw in the Na’vi case was that individuals joined the fan community because “Avatar” was very tied to environmental rights and indigenous rights. These ideals of environmentalism are part of the language, and they picked up on that. That is part of the reason that some of them were learning the language.

What about other invented languages?

The ones that are learned most widely are those intended as an international auxiliary language, like Esperanto, meant to be shared by people around the world to promote unity and world peace. It’s supposed to be a neutral language, and it’s simplified and very easy to learn. It’s been learned by millions of people around the world. You can learn it on Duolingo!

The other ones are fan languages: Na’vi, Klingon from “Star Trek” and Dothraki from “Game of Thrones” are very popular. There were 300 Na’vi speakers when I surveyed them in 2011, everyone from beginners to very advanced — but they all considered themselves part of the community. Dothraki speakers were much fewer at the time, maybe 20. And studies have shown there are about 20 advanced Klingon speakers in the world as well. It depends on the popularity of the show at the time. If another season of “Star Trek: Discovery” comes out, you will have more people learning Klingon.

We definitely see that with Na’vi. It was very popular early on, and there are still those core members who are learning Na’vi. And with “Avatar 2,” which is supposed to be coming next year, we will likely see an increase in speakers.

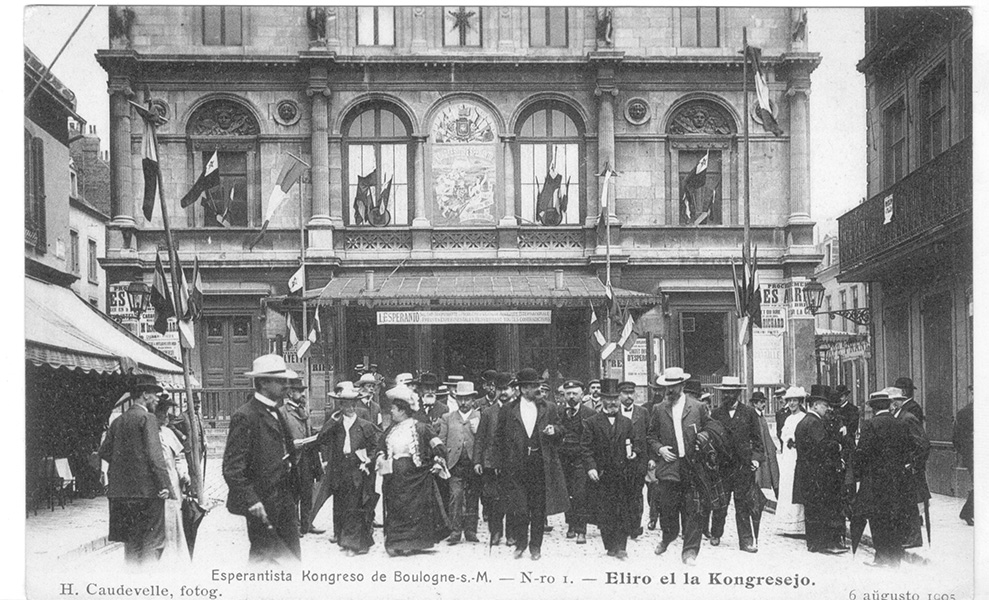

Participants at the First World Esperanto Congress in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, in 1905. Esperanto was designed by its inventor to be an international language that would unite people from all nations under a common tongue.

CREDIT: HENRI CAUDEVELLE / PUBLIC DOMAIN

How do you construct a language?

I personally always start with sound systems, because the backstory has usually been developed for me. We know who Superman is, we know what planet he’s from, and there were already a few words, like Jor-El and Kal-el, Krypton. I took those words and developed a sound system, the sounds of the Kryptonian language. From there, I decided how words would be put together and how they’re broken into their individual parts, like suffixes and prefixes, that tell you if something is biological or technological, plural — all those pieces.

I also had to figure out how sentences are put together, and whether nouns come after adjectives or adjectives come after nouns. And I developed irregular changes to the language which mirror natural language. For example, in English we have sounds that become more nasalized, where the air is going into your nose when a nasal sound appears after. If you say “beet” versus “bean,” you can hear that the vowel is becoming nasalized in “bean,” because you’re getting ready for the N.

Many natural languages have this, so I did similar things, where sounds would change depending on if they were at the end of a word or if a sound is coming after them. In “Alpha,” another movie I worked on, I made a regional dialect. Even if people don’t notice it, it helps create the authenticity of the language, which is what a lot of film production companies are interested in.

That’s a lot of work. I would have thought that production companies would be interested in the cheapest option.

That’s the “Star Wars” way! “Star Wars” has been critiqued for just making random sounds. It’s gibberish — there’s nothing behind it, just sounds. Movie producers very rarely would want to do that anymore, because viewers are so much more discerning.

And that’s what led you to films — tell us how that happened.

When I completed my survey of Na’vi speakers, there was a newspaper story about me and my work and how it tied to endangered languages. Alex McDowell, who was the production designer for “Man of Steel,” read it while flying from Chicago to Vancouver. They were in the middle of filming, and they knew they wanted to have a written Kryptonian language all over the set, but they hadn’t considered that it had to be an actual language. As soon as he read the article about Na’vi, he realized that he was going to have gibberish, and that’s not OK. So when he landed, he had his assistant email me, and I was there within the week.

Are there other reasons people invent languages?

People who invent languages are hugely diverse. There are people who start making languages when they’re 8 or 9 and start building worlds in their imagination. The writer J.R.R. Tolkien was famously known for making languages and then writing “The Lord of the Rings” to put his languages in. There are people who want to see the world in different ways. People who want to promote a language that is used instead of a colonial language, like Esperanto was used to be a language for the world. There are people like me who make them for pop culture, or there are people who make them to play with language, because they’re just really fascinated with linguistic structures. Some people try to make a language with only verbs. Some try to avoid adjectives.

One very simple invented language is Toki Pona. It has 123 words. The idea is that you can just learn this set of words and anything you want to say can be said by combinations of those 123 words. Then we have very complex languages like Ithkuil that were invented to avoid the ambiguity in most real languages.

In 2018, the Royal Albert Hall in London announced that people who spoke Klingon when booking tickets to “Star Trek in Concert” could win free tickets. This forced the call center to make sure they had Klingon-speaking staff, such as those shown here.

CREDIT: JOE PEPLER / WENN RIGHTS LTD / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

English, for example, doesn’t specify how we know a piece of information. If I say I know it’s cold out, how do I know that? Is it because I saw it on my thermometer? Did I feel it with my body? Did someone tell me? Some other languages, natural languages, make this distinction with what are called evidentials. You add something to your verb that says I know it because I felt it with my body, or whatever. Navajo does that. This is what some of these ultraprecise invented languages do, on even bigger scales.

You started down this path looking for lessons you could apply to your other academic work, on endangered languages. How do invented languages compare with endangered ones?

I would say that they are endangered languages. Endangered languages are ones that are not being taught intergenerationally by parents to children. They have small numbers of speakers, they are low in prestige, they often don’t have writing systems, they’re not official.

I was interested in looking at these individuals from fan communities that are learning languages quite quickly. What were they doing? How were they learning the languages? They would often have members of the community make online dictionaries, and post lessons, and do other things that are innovative to help people learn. I looked at that to see how endangered-language communities might be able to model the learning processes of these fandoms.

Did you learn anything useful for the conservation of endangered languages?

Around the same time I was working on the Na’vi study, I was working with the Taku River Tlingit First Nation in British Columbia. We were developing an online database to document place names throughout their territory and provide a space for individuals to learn those names. One of the things I learned from the Na’vi community is the importance of having audio files and imagery, a place for people to talk to each other, linking it to social media. Having a welcoming phrase at the beginning of the website. On the “Learn Na’vi” forum, it says “kaltxì” —which means “welcome to our community.” We brought a lot of these things into the Taku River Tlingit place-names website.

What’s the easiest invented language to learn?

Ooh! Ones that are meant to be simple are probably the easiest. I might say Esperanto. People also vote for Toki Pona.

But it depends on who you are. If you’re a fan of “Star Trek,” you might have that passion and drive to learn Klingon, so that might be easiest for you, despite the fact that it’s a very hard language.