Most economists agree that college is a wise investment. People who complete four-year degrees typically earn more than people who only finish high school, and they report higher levels of financial well-being across their lifetimes, such as more retirement savings. Countries with more educated populations are wealthier, achieve greater innovation and have more engaged citizens.

But who should pay for college? Individuals who receive college degrees? Or the government, using income collected from taxpayers?

The United States, most of the United Kingdom and Australia are among the places that require students and their families to pay for college, while many countries in continental Europe draw more on public funds. Yet even countries like the United States rely on taxpayer dollars to support students who do not have the cash to pay tuition out of pocket, or the credit required to borrow large sums from a private lender, says Constantine Yannelis, an economist at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

There’s a strong economic argument for government investment in higher education for students from less advantaged backgrounds, who stand to benefit most from government-backed loans, Yannelis and his coauthor, Columbia University economist Greg Tracey, write in a 2022 article in the Annual Review of Financial Economics. But for complex reasons, the way that the United States has structured its student loan system has led to a massive increase in student debt over the past two decades, spiraling from $364 billion in 2004 to a balance of roughly $1.7 trillion owed today.

When an individual can’t pay that debt and defaults on a loan — technically defined as missing nine months of payments — it can damage their credit rating and make it difficult or impossible to get future financial aid or qualify for a loan to buy a house or car, which can have an outsized effect on their lives and could be a drag on the economy in the long-run.

A new policy to help struggling borrowers, the Save on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan, will go a long way to ease the financial and psychological hardships student debt imposes on the most vulnerable borrowers, says Yannelis. But more work is needed to fix the US student loan system and ensure that investing in higher education leads to greater financial health, rather than less, he says.

Knowable Magazine talked with Yannelis about the complex drivers of rising student debt, what can be learned from other countries’ approaches to supporting higher education, and what US borrowers need to know as the pandemic-driven moratorium on student debt repayment ends.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Just how big is the US student debt burden?

The outstanding student loan balance is about $1.7 trillion. That’s a massive number. It’s similar to the gross domestic product of major countries like Russia or Brazil. The typical federal student loan borrower owes almost $40,000 and there are about 45 million student loan borrowers. So this is a very large balance of debt affecting tens of millions of people. Only mortgage debt is larger in the United States.

Who is most affected by student debt in the US?

There’s a lot of heterogeneity. But the graduates of for-profit colleges — places like the University of Phoenix and the now-shuttered Kaplan University, which aren’t selective in their admissions policies and charge high tuition fees — predictably, these graduates do much worse than other student loan borrowers. They have much higher default rates, much lower earnings, and very high loan balances relative to their earnings. Minority and particularly Black borrowers tend to have higher loan balances and higher loan default rates. Women tend to default less than men, and are also starting to outperform men in terms of college completion. So, if I were to focus on groups that I am concerned about, it’d be graduates of for-profit colleges, people who drop out, Black borrowers and men.

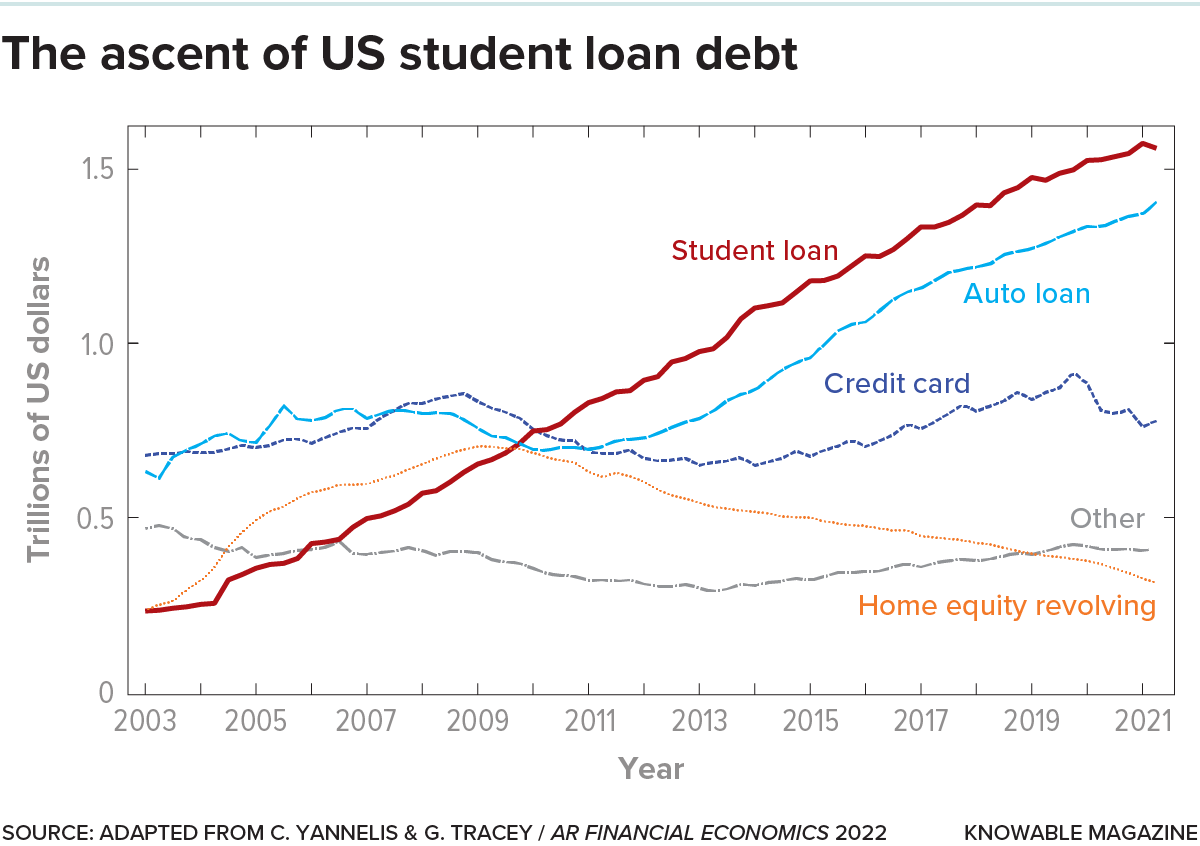

US student debt has increased more than any other form of consumer debt over the past two decades, with the exception of mortgage debt, which is not shown here.

Why do you say it’s “predictable” that graduates of for-profit colleges do worse?

You see it in the data: Certain schools have high student loan default rates year after year.

In my work with Adam Looney, we have shown that over the past 30 years, about 90 percent of the variation in loan defaults is driven by government policies expanding and contracting credit to for-profit colleges and changing the share of student enrollment at those schools.

When the government expands the amount of credit available for student loans, for-profit colleges expand enrollment and increase tuition fees. This basically drives all the variation we see in the number of people who default on their loans. For-profit colleges account for only about 10 percent of student enrollments in the US, but about a quarter of student loan borrowers and about half of loan defaults. They make up a disproportionate number of bad outcomes. The upshot of this research is that we can solve a lot of problems by focusing on a relatively small number of schools.

Are for-profit colleges responsible for the recent increase in student debt, too?

In terms of what’s driving the total load of student loan balances, there are a lot of factors. Some of them are quite negative. Others are neutral, and others are actually positive.

Unlike other types of household debt, US student loan debt has just gone up and up over the past 20 years. Since 2000, the amount that students owe has increased by more than 600 percent. We haven’t seen that at all in other forms of debt, even during the housing boom in the 2000s.

One reason is an increase in government credit: The government has raised limits on how much students can borrow, and schools have captured some of those increases by raising tuition.

You can also point to the demographics of the population: That’s changing a little bit now, as fewer people enroll in college, but over the past 20 years, we’ve had fairly large cohorts of people going to college. There were about 13 million undergrads in 2000, compared with almost 19 million today.

Another factor that’s often overlooked, which is not such a bad thing, is that over the past 15 years, the government has introduced a lot of programs that allow borrowers to essentially extend the lifetime of loans, by making smaller payments when they’re fresh out of college. That leads to higher loan balances, if people are repaying their loans over a longer period, or even not making any payments at all. But it’s less of a hardship for people if they make smaller payments as a portion of their income.

How does community college fit into the picture? Isn’t that supposed to be an affordable alternative?

Yeah, that’s one thing that I forgot to mention: Another one of the reasons for the increase in student loan balances is budget cuts. Community college is more expensive than it was in the past, and under-resourced, because unfortunately, when states run into fiscal trouble — as many did during the housing crisis — one of the first things that they cut is education spending.

Community colleges do better than for-profit colleges in terms of the amount of debt their students take on and how often they default on their student loans. But community college is also more expensive than it was in the past, and there’s overcrowding. Community colleges are not deliberately predatory: They’re not thinking about maximizing revenue at the expense of students. They just have very limited resources and many other constraints.

You mentioned that as government support for student loans increases, tuitions tend to rise too. How should policymakers tackle that?

The core of the student loan problem is that borrowers borrow from the government, and then pay tuition to schools. So if schools are behaving in a predatory way — like for-profit schools — their incentive is to sign up warm bodies, get them to take out government loans, and then, if the borrowers default, it’s the taxpayer’s problem. It’s not the school’s problem.

To fix this, policymakers could make schools’ payments contingent on outcomes. Brazil did this in 2017, essentially giving schools skin in the game and making them pay a fee for high dropout and default rates.

I’m studying the effects of this reform now, and it’s not yet clear whether this policy is desirable or not: The big concern is that schools might improve their outcomes simply by taking fewer borrowers that come from more challenging backgrounds. And that, of course, would be a terrible thing. We want to be very careful to make sure that schools are incentivized to improve quality, but not punished for taking on students from challenging backgrounds.

Let’s talk about the pause on student loan repayments in the US which began in March 2020. How did that affect borrowers?

I’ve studied that question with Michael Dinerstein, who’s in the University of Chicago economics department, and a great graduate student here at Chicago Booth, Ching-Tse Chen. We wanted to know how the student loan payment moratorium in 2020 affected borrowing and consumption outcomes.

To study this, we used an institutional quirk in the ownership of loans. Some federal loans are owned by the government. Others are owned by private banks and guaranteed — meaning that the government would pay the banks if the loans were to default.

For arcane legal reasons, only the loans owned by the government saw a freeze in 2020, so you had something that approximated a natural experiment, with some people still paying on their loans and others not.

We used this feature to generate quasi-experimental variations. And we found something that surprised me, at least. We saw that individuals included in the payment freeze ended up borrowing more in other types of debt: mortgage loans, credit cards and auto loans. We also found no effect on other loan defaults — meaning that people defaulted just as much on other types of loans as they did before the pause — which was also surprising.

Our findings are generally consistent with people having more cash on hand and being able to make down payments. It also suggests that policies like loan moratoria can have perverse effects, and lead to more debt in the long run.

What you’re describing sounds like an economic stimulus, if people were spending more on things like houses and cars.

Exactly. So in terms of the policy implications of that finding, there’s a glass-half-empty and a glass-half-full way of looking at it.

The glass-half-empty way is that these households will have more debt in the long term, which could depress consumption several years later. The glass half-full way is exactly as you mentioned: This is a very cheap way of doing stimulus.

If you look at writing stimulus checks directly, or other policies we tried during the pandemic, those are costly because the government pays directly. Whereas if we freeze debt payments, most of those dollars will be repaid later. So as a cheap way of doing stimulus, the policy worked.

Are you worried about what will happen as US student loan repayments start up again?

I’m less concerned about the resumption of student loan payments than I was six months ago. I was really concerned that this payment resumption would be a disaster, but I think that the government took some steps that were quite sensible to alleviate potential concerns.

One is something that the government is calling an “on-ramp” in terms of student loan repayment. It means that borrowers don’t actually have to make payments for a year — or to put that more precisely, if they don’t make payments within that first year, it won’t damage their credit scores and the loans won’t go into default.

What will happen is that interest will accrue. So, there’s some cost to not making payments during this period, but it’s not a catastrophic cost. I think that’s important, because we’ve had a lot of people who have not been making payments for three years. Now they’ve lost touch with their loan servicers, they may have moved during the pandemic. Many major loan services, like Navient, exited federal student loan servicing, so those loans were transferred to other companies. People may think it’s a scam if some company they’ve never heard of tells them that they owe student loan payments. I think it’s fantastic that this on-ramp is occurring — it will give people time to get their lives in order.

Another good thing that’s happening is that a new income-driven repayment plan was introduced, the Save on a Valuable Education plan. Income-driven repayment plans link the amount of borrowers’ payments to their incomes. The way they work is that people pay a fraction of their income above the federal poverty line.

This new plan increases the threshold of the federal poverty line above which borrowers must pay. So, if you’re fairly low-income — earning $32,800 or less for individual borrowers, and $67,500 for borrowers with a family of four — you don’t pay at all. Low-income borrowers will make very small or no payments under this plan, and for many people loan balances will be forgiven after a decade.

That’s restricted to undergraduate borrowers, right? If you have debt for graduate school, nothing changes?

Yeah, exactly. Something to keep in mind is that on average, people who go to graduate school earn more than people who don’t. If you plot incomes by student loan balances, it’s the people with big student loan balances who are earning the most. People like doctors, lawyers, a lot of professionals who have MBAs, many of them have high student loan balances, but they also earn a lot of money.

Student debt is the only debt where people with lower loan balances default at higher rates than people with higher loan balances. And that’s because there are a lot of people, like people who drop out of college, or people who only get two-year associate degrees, whose debt levels may not be as high as other people, but whose earnings are also very low, and they’re really struggling.

How do other countries finance college? Is there anything that the US could learn from different systems?

Broadly, there are two models of financing higher education. There’s a model that’s seen in continental Europe and in a lot of Asia, where education is funded by taxpayers. People often call this “free” college. But it’s not free, because professors still have to be paid, you have to build buildings. So somebody’s paying for it. It’s financed by all taxpayers rather than the people who go to college.

A problem with the taxpayer-financed systems where people don’t pay is that, in many European countries, for example, you have so-called students for life, or eternal students, who are spending far too long getting a degree. There’s interesting work from Italy in which one prestigious Italian business school introduced very small tuition fees. That led to people speeding up their graduation, because they had to pay something that was nominal.

The other model is the one that you see in many English-speaking countries. The UK, Canada and Australia have a similar model to the one in the US, where students pay directly, but with a bit more government subsidy than we have here. These countries all have government-backed student loan programs as well.

There are a few things these countries do quite well relative to the US, especially in terms of income-driven repayment programs. In the UK and Australia, for example, everyone is automatically enrolled in an income-driven repayment plan that is administered by government tax authorities, and that automatically takes student loan payments out of their paychecks. This is a very progressive way of doing things compared to the continental European model, because you only pay if you go to college. If you went to graduate school, and you earn more, then you pay more.

It’s progressive because you don’t end up levying certain taxes — payroll taxes for example — on people who didn’t go to college, and earn less, on average. The fact that these programs are administered through the country’s tax authorities means that the administration is very easy, and you don’t have all these problems like loan defaults, and people destroying their credit scores and not getting in touch with their servicer.

One low-hanging fruit for improving the system we have already in the US would be to enroll everyone in income-driven payment plans and administer the payments through the IRS. That would eliminate problems related to loan default and provide a lot of forgiveness to low-income people without spending tens or hundreds of billions of dollars helping high earners like MBAs and doctors.

Some argue that blanket loan forgiveness plans like the one that the Biden Administration proposed — which would have canceled $10,000 in debt for those earning less than $125,000 per year — would help alleviate racial inequality. Do you agree?

It would lower racial wealth inequality, but the benefits would be minimal. According to my calculations, forgiving all $1.7 trillion in student debt would lower the racial wealth gap by about 3 percent. Currently the median Black household in the US has around $24,000 in savings, investments, home equity and other kinds of wealth. The median white household has around $189,000 — nearly eight times the wealth of a median Black household. We want to close the racial wealth gap as a society, but I think we’ll all be quite unhappy if it’s only closed by 3 percent. The racial wealth gap is largely driven by differences in income and real estate value, not student loan burden. So, if we want to spend $1.7 trillion, we should be thinking about things like early childhood education or investing in poor, Black neighborhoods to increase property values.

Beyond not doing enough to close the racial wealth gap, blanket student loan forgiveness is just a very regressive policy. In my work with Sylvain Catherine at the Wharton Business School, we found that individuals in the top fifth of the earnings distribution would receive five times as much debt relief as people in the bottom 20 percent of the earnings distribution. There are much more effective ways to target the racial wealth gap without this huge problem of making big transfers to higher-income people.

What advice do you have for prospective students — and their families — considering whether to take out a loan?

College students should be asking themselves whether the degree they are considering enrolling in will pay off in income. There are a lot of great resources, like the Department of Education’s College Scorecard, that people can look at to get a sense of what their realistic earnings are likely to be.

Editor’s note: This article was updated on October 11, 2023, to correct a statement about how the United Kingdom funds undergraduate education. Unlike other parts of the United Kingdom, Scotland generally pays undergraduate tuition fees for residents.