Is ongoing hostility in your marriage making you stressed or depressed? Do you have a good relationship, but your partner has a chronic disorder? In either case, watch out. Though married people, on average, have better health than others, partners in these two situations can face an increased risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease and other conditions. The risks vary, of course, but take note: If one spouse is obese, the other person’s risk for that condition doubles.

Janice K. Kiecolt-Glaser, director of the Institute for Behavioral Medicine Research at Ohio State University, and Stephanie J. Wilson, a postdoctoral researcher in Kiecolt-Glaser’s lab,study the health effects of intimate relationships and recently reviewed the topic in “Lovesick: How Couples’ Relationships Influence Health” in the Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. Here, they explain some of the more intriguing findings. The interview has been edited for clarity.

Is it true that, overall, being married is good for you?

JKG: A bunch of different studies show that marriage, on average, is beneficial for rates of disease, recovery from surgery, cancer risk — most of the things you can look at. The effects of being single are similar in magnitude to the health risks of smoking, high blood pressure, obesity or a sedentary lifestyle.

SW: A recent meta-analysis showed that the effect of a quality marriage on physical health was about equivalent to that of daily exercise or a healthy diet. Maybe over a short time span the effects are not large, but over the course of longer periods, the benefits of a satisfying marriage add up.

Now the flip side. Studies show that the risks for obesity-related conditions rise dramatically in a person if a partner has the condition — risk doubles in the case of obesity itself and rises by more than 25 percent for diabetes and metabolic syndrome. What explains this “contagion”?

JKG: If your partner has less healthy behaviors, it gives you license, and perhaps subtle social pressure, to adopt them as well.

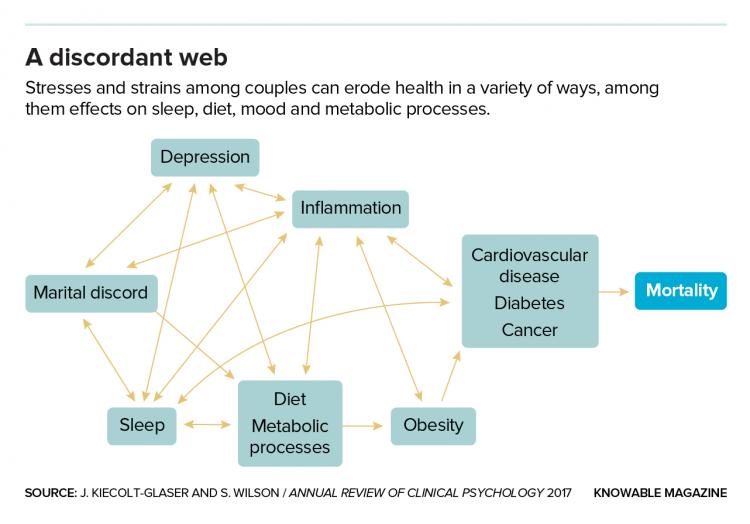

Being stressed by ongoing marital discord also aligns with poor health. What are common effects?

JKG:Cardiovascular disease has been well described, hypertension has been described in a variety of cases — the whole metabolic syndrome group of diseases. Marital discord doubles the risk for metabolic syndrome.

SW: A lot of the chronic illnesses that develop at higher rates in couples who are unhappy than in satisfied couples may be caused in part by inflammation. Beyond that, once a person has vulnerability to a disease, its severity can be exacerbated by marital discord. I am thinking of certain pain conditions that may not be rooted in inflammation or stress per se but, once they arise, might escalate more quickly in someone who is in a poor marriage.

Also, marital distress and depression are strong fellow travelers. An unhappy marriage is really, really fertile ground for depression, and depression has very well documented health consequences. And it goes back and forth. People who are depressed are more likely to have marital troubles, because it’s not fun to be around someone who is depressed.

It sounds as if most roads lead through inflammation.

JKG: It’s one of the central pathways we know the most about these days, although there are certainly others. Inflammation is associated with a variety of different diseases. And psychological stress can promote inflammation.

What is the biological route from stress to inflammation?

JKG: When you are stressed, stress hormones respond. For instance, norepinephrine, otherwise known as noradrenaline, is clearly very stress-responsive, and it is also a hormone that is important on the pathway to inflammation.

“If your partner has less healthy behaviors, it gives you license, and perhaps subtle social pressure, to adopt them as well.”

Janice Kiecolt-GlaserBehaviors also change as a result of marital stress. How do they link to ill health?

JKG: Most of us don’t tend to eat more broccoli when we’re stressed, or all the things our mothers told us to do: eat healthily, exercise, drink moderately. Those are all behaviors that, with stress, get worse.

SW: Sleep is particularly important for health, too, and is disrupted by marital stress.

Can these effects contribute to inflammation?

JKG: All the behaviors we’ve been talking about are also lovely for inflammation. When you are eating a high-fat, unhealthy diet, it’s inflammation-producing. Drinking heavily, smoking, sedentary behavior — they are all associated with inflammation. Depressive symptoms have inflammatory consequences, too.

SW: Sleep disorders are also associated with much higher levels of inflammation and predispose you to a range of chronic illnesses, but we have also found that just a night or two of less sleep primes couples to have a larger inflammatory response to conflict than couples who had more sleep in the past two nights.

How does one go about showing that marital discord affects physiology?

JKG: In the earlier studies in our lab, we would bring couples in and put a catheter in their arm and ask them to discuss a disagreement, and we could watch stress hormones in the blood respond to the quality of the disagreement. When people were more nasty or hostile, we would see much larger increases in stress hormones. You could actually watch the biological consequences related to the quality of the discussion.

“So we have a triad of really unhealthy things happening associated with depression and couples’ negativity or discord.”

Janice Kiecolt-GlaserHow do you get people to have disagreements in the lab?

JKG: We have people fill out an “areas of disagreement” questionnaire, where they rate the intensity and chronicity of common marital problems — in-laws, finances, sex. Then they are asked to resolve problems they have identified as current issues, such as, “What are you going to do about Mrs. Jones’s mother who keeps dropping by unexpectedly?” We videotape that discussion and then code what the partners are doing.

What do you look for, specifically?

JKG: Bad marriages often have the same kinds of symptoms. One classic signature of distress is the demand-withdraw pattern, where one person will be saying they want a change in something and the other person doesn’t want to discuss it. Another signature is negative escalation: One person says something negative, the other person responds in kind, and it goes up and up and up.

Jan, you did a study showing that marital distress can alter metabolism in ways that promote weight gain. How did you make that discovery?

JKG: We were trying to mimic the amount of fat and calories in fast-food meals — the things that people would turn to when stressed. We brought couples into the laboratory and we fed them one of two high-fat meals (one with a healthier fat, high oleic sunflower oil, and one with a saturated fat). Both were 60 percent fat and 930 calories. We drew blood and made metabolic measurements at baseline and every two hours after the meal throughout the day, including one and four hours after the disagreement discussion.

We found a whole series of things, for both meals. When a person had a history of depression and the conflict was nastier, they had higher and more sustained rises in triglycerides, and their metabolic rate was lower: Energy expenditure went down by 128 calories. That’s not a big deal for an afternoon, but it could add more than 7 pounds of weight a year for someone with continuous stress over time. There was also higher insulin production, which is a way of telling cells to store fat.

So we have a triad of really unhealthy things happening associated with depression and couples’ negativity or discord.

Do you see gender differences in responses to marital distress?

JKG: I would argue that it’s more the woman who gets affected. A meta-analysis by a former grad student did not find that, but they did not look at the kinds of laboratory studies we do (they are costly and intense and not commonly done). In those, we clearly see that women are responding more physiologically.

There is a large psychological literature, too, showing that women remember both positive and negative events in much more detail than men; women ruminate or think about those relationship events much more than men. So it would be surprising if there were not greater health effects for women. In our laboratory studies where we had the catheter in the arm and were drawing blood during the conversation, we could really see the differences in how the women were responding compared to the men.

Research also shows that, at the other end of the spectrum, having a really good relationship can put a person at risk for health problems if the partner is ill. What goes on there?

JKG: Some of the best evidence comes from the extreme case of spouses caring for partners with Alzheimer’s disease. Years ago, we showed that the spouses’ immune systems were less likely to respond to vaccination as they should; spouses healed wounds more slowly; they had higher levels of inflammation. That’s the more extreme case, but there is now good evidence across less-dramatic illnesses that a spouse’s illness matters. And it appears to matter more in a better-quality relationship — because it affects you more directly, in some ways.

SW: Another type of lab study brings in a couple where one person has a chronic pain condition, such as knee osteoarthritis that affects the ability to get around. The pain patient would be asked to do a painful task and would be video-recorded. That video would be shown to the spouse. Spouses react with greater blood pressure increases to watching the patient in pain compared to somebody they don’t know, and beyond that, spouses who are in happy marriages show even more exaggerated effects.

Is the mechanism similar to what happens when partners have marital discord?

SW: The stressors and experiences are likely to be different — empathic processes and the stresses of care-giving, rather than noxious conflictual patterns. But the physiological pathways might be the same.

JKG: What happens in partner illness, too, is that the ill person is typically less available, so the partner loses many of the positives of marriage, such as the give and take of conversation and shared experiences.

Elderly couples in a happy marriage face a greater health risk than younger people do when a partner is ill. Why?

JKG: Older couples have longer, more intense relationships. Also, the older someone is, the more vulnerable they are physiologically. Stress for someone in their 20s is not likely to make them sick or have huge health effects, but we know that when someone is 65 or 70, noticeable declines in the immune response begin, and age-related increases in inflammation. So you’re adding stress onto physiology that is already functioning more poorly. But there is also a psychological explanation.

SW: In general, as people age, there is a decrease in the size of the social network, a greater emphasis on relationships that are emotionally meaningful. Because of that, psychological weight is placed on the marital relationship.

“Over the course of longer periods, the benefits of a satisfying marriage add up.”

Stephanie WilsonWhat about the health effects of stress on gay couples or people who cohabitate?

SW: Most of the studies only recruit heterosexual married couples, and that’s the only group we can strongly generalize to. But the existing data don’t show marked differences in the process in cohabitating or homosexual couples.

Is there a particularly good way to protect health when couples have marital problems?

JKG: There is some evidence that marital problems are going to be most responsive to marital therapy (as opposed to individual therapy). It can address the utility, or lack of utility, of the way couples are thinking about particular problems.

SW: And it can encourage making an effort to take the other person’s perspective and to approach problems as a team. We only have a few studies to look to. But they’ve shown that, regardless of the specific approach, if the therapy is effective at reducing marital problems, we see a reduction in stress hormone reactivity.

To limit marital tension when one partner is ill, the advice to a spouse seems to be “Be supportive.” But how do you do that without seeming to be a nag or too critical?

SW: A lot of this work has shown that supporting the person in their independence — essentially saying, “I believe in you; this is a challenge, but you can do this” — can build a partner’s self-confidence, which is often going to be beneficial. Being empathic has also been shown to be effective — listening actively when the partner wants to share, to show that you are there as a support, and being generally loving and warm.

CREDIT: MARMAX/PIXABAY (CC0)

In your own relationships, have you used anything you’ve learned from the research?

JKG: Yes — the idea that you pay attention to your relationship; that it matters how you talk about it and think about it. And it matters that you take good care of yourself, as well as attending to your partner, when your partner is ill.

My husband has Alzheimer’s disease. When he was first diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, I saw the train coming down the tracks. Ours is a case where our lives were very much intertwined. He was my primary research collaborator and we had a really good relationship and a closeness. So I tried to make sure that I had my own life aside from the marriage, in terms of friendships — not just couple friendships — and I tried very hard to take care of my own health. I knew all too well what happened when people didn’t take care of themselves.

Don’t breakups cause all kinds of anxiety, depression and stress too? And then there is loneliness. Which is worse for one’s health — staying in a non-ideal relationship or going it alone?

SW: The evidence is mixed. One study found that singles had lower resting blood pressure than unhappily married people but a study of people with rheumatoid arthritis found that singles and the unhappily married were in an equal amount of pain. In both cases, happily married people fared best. As for divorce, most people cope well and recover quickly post-marriage, but a consistent minority (10-15 percent) do struggle and face heightened health risks as a result. As for loneliness, it is possible to feel lonely in a marriage; surrounding oneself with other friends and family seems to be especially important for staving off loneliness in the unmarried.

Where is your research heading now?

JKG: Stephanie and I are working on a microbiome project. We are recruiting couples and getting fecal samples to look at how marital quality and marital stress are reflected in the mix of bacteria in the gut.

What would you do with that information?

JKG: The microbiome may well be an important conduit to inflammation. With what’s called a “leaky gut,” you have endotoxin, a bacterial toxin from certain bacteria, leaking across the gut barrier. That fuels inflammation. We can look at how a person’s diet affects their microbiome, whether dietary interventions might be useful for reducing inflammation in people experiencing stress in their marriage — a variety of things. So the research offers the possibility for finding interventions that we might not otherwise have thought about.