On a spring day in 1972, physician Pekka Puska, 26 and fresh with ideas and vigor, blew into the far eastern province of North Karelia, Finland, like a bracing north wind. Backed by government and public health authorities anxious for improvements, the young doctor brought with him newfangled and officially sanctioned but unproven plans about what to do for the people of the region. Many provincial citizens were women widowed by a cardiovascular assassin that had torn away their husbands and left fatherless children who smoked by the time they reached middle school.

Puska arrived as head of the North Karelia Project, by way of a petition from Esa Timonen, the regional governor. Seeing his constituents weathering early death after early death, the governor lobbied vigorously for something to be done. Puska and his team were the something, and what Puska wanted was to overhaul how residents of North Karelia lived, ate and drank. The guiding framework for the project, given the blessing of the Finnish government and the World Health Organization, was to go after three targets — hypertension, cholesterol and smoking — to prevent cardiovascular disease rather than waiting for it to develop and kill.

A North Karelian citizen has his blood pressure checked in 1972, as part of a baseline health assessment of the province’s population.

CREDIT: NORTH KARELIA PROJECT

Puska and his band of self-described “radicals” saw many routes to these targets, and they tried every one — media campaigns, community meetings, chats in people’s kitchens, carrots and sticks for farmers and food producers — up to and including village-versus-village competitions over cutting back on smoking or reducing cholesterol counts. The tactics even included one of the earliest reality TV shows, a sort of “Biggest Loser” from the late 1970s called “Keys to Health.” Hugely popular, it featured occasionally wretched-looking Finns willing to have their cholesterol levels and smoking habits tracked on national television.

A crucial winning weapon for Puska and his team was in the home. Men largely ran the government and the health programs, but women in the 1970s still ran the kitchen, controlling what came in and what made it out to the table. In general, they liked Puska’s message. Sick of losing husbands too soon, weary of widowhood and fatherless children, they took the mantra of lower salt, lower fat and more vegetables to heart, and brought the Puska plan to individual family tables.

The numbers coming out of the project, now grown into a model endeavor in its 45th year, show, as of 2012, an 82 percent reduction since inception in deaths from coronary disease among middle-aged men locally. The project went national in its fifth year, as planned, and Finland saw an 80 percent drop in such deaths countrywide by 2012. The changes are largely credited to Puska, now a member of the Finnish Parliament, and the government that facilitated his work. The effort has spawned more than 1,100 related scientific publications and 65 dissertations.

Yet questions, perhaps unanswerable, remain. The project was not — could not easily have been — a completely controlled experiment. Scholars say it’s difficult to tease out which tactics of the North Karelia Project definitively helped to reduce rates of heart disease and related deaths, and to what extent — information necessary for applying the approach elsewhere. Some researchers note that the world did not sit still as the Finnish experiment barreled forward and that changes not explicitly related to the effort could also have helped heal Finland’s hearts.

Still, there is broad agreement that the North Karelia Project blazed a trail as a populist public health success. It took a medical issue out of the clinic and into the culture and tried to change that culture; other nations and regions, including ones in the United States, have sought to employ a similar approach, with varying payoffs. A key success of the North Karelia Project is that its tactics percolated the idea of risk factors into the public consciousness, especially lifestyle factors that people can control for themselves — a “remarkable” shift, says sociologist Glorian Sorensen of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “It was really one of the first studies of its kind,” she says. “And it was very early in thinking about how social factors may really shape health behaviors that are associated with chronic disease.”

The spoilage of war

The specter of the Second World War looms large over Finland even today. Men whose fathers fought in the war — against the Soviets at the Karelian border in the Winter War and the Nazis in the northernmost reaches of Lapland — will not fail to mention the family’s service. The war still seems to shadow the national psyche, and none were hit as hard as the men who fought in it. Returned home to a country that lost on many fronts, these men also returned to a nation and economy in flux.

The Finnish government rewarded its veterans with plots of land, but men of the borderlands were used to cutting down trees for a living. Turning to familiar ways and easy stock, they deforested the land allotted them and used it to rear cows and pigs. Where fish, game, rye bread and root vegetables once ruled the day, salt pork and dairy cream took over in the 1950s and 1960s. Where some plants had once fed humans, the stock animals got the bulk of the greens instead.

Days were filled with the haze of cigarette smoke — a habit picked up during service — the briny smell of salted meats from the pigs, the heavy aroma of fatty cream and butter from the cows, and the eye-watering sting of alcohol numbing the psychic scars of war. It was, as one resident put it, a life burdened with the “curses of the borderland.”

At this crossroads of diet and drinking and depression, men began to die, young and suddenly, of cardiovascular disease. The rates in 1969 — 643 of 100,000 men aged 35 to 64 annually — were so striking, so high compared to the rest of the world that the public health authorities couldn’t help but take note. Finland’s death rates from coronary heart disease were two or even three times those of other European countries and Japan. And nowhere were they as high as where Finland had lost a frontier to the Soviet Union: the eastern province of North Karelia.

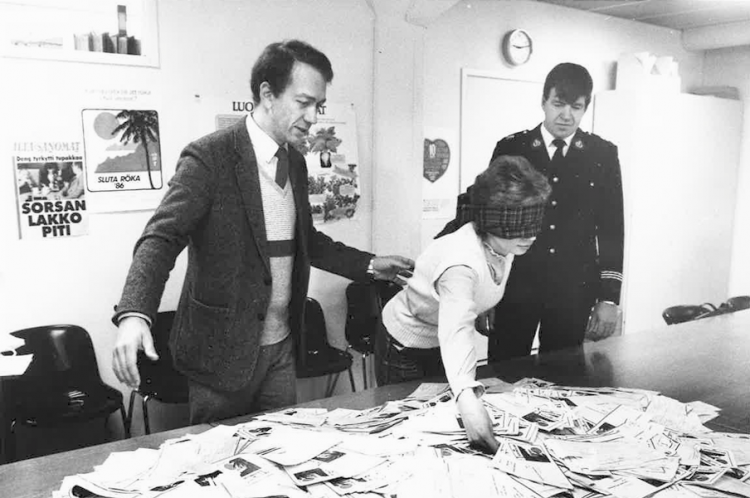

Prizewinners for a 1986 “Quit and Win” smoking cessation campaign in Finland are selected by a blindfolded volunteer, as Pekka Puska (left) looks on.

CREDIT: NORTH KARELIA PROJECT

The Seven Countries Study, a famous long-term project begun in the late 1940s, compared how dietary and other practices in different regions influence health. Finland was included in a special comparison, the East-West Study, pitting cardiovascular data for people in the province of Western Finland against those of North Karelia. Results from the late 1960s pinpointed the eastern province as ground zero for the devastation that poor diet can wreak on cardiovascular health.

The message machine

The spokes of the North Karelia Project and its expansion, with Puska’s team as the hub, touched seemingly every aspect of Finnish life. There were leaflets, posters, fireside chats at domestic hearths and community gatherings to rally citizens around reducing the province’s collective and individual cardiovascular risk. Schools, doctors and nurses joined in. Newspapers and radio carried the message throughout the province — more than 1,500 related articles were published in the first five years — with national media jumping on board when the project expanded beyond North Karelia. Regardless of the medium, the relentless messages never changed: Reduce salt to lower blood pressure. Stop smoking. Cut saturated fat to decrease blood cholesterol numbers. Eat more produce, less meat.

Puska will tell you that the people loved him and his team, and their messages. But, he notes, it wasn’t always love at first sight. Buy-in from food producers was crucial, and the dairy farmers were so opposed to the efforts to change local diet — after all, their livelihoods relied heavily on dairy fat — that ultimately they started a bitter battle over butter known as the “fat wars.” But the wars faded after peaking at the end of 1980s as the farmers, aided by legislative changes designed to promote the health endeavor, found other ways to make money from their resources, including exporting their fat to willing consumers outside of Finland.

Many who took advantage of the new economic framework flourished. Laws that had overwhelmingly favored dairy fat production (subsidies for milk fat and butter, laws that banned mixing butter-only products with vegetable oil) shifted to support other products (subsidies for protein, an end to the fat-oil mixing law). With the emphasis on lower-fat milk, cow-breeding took a turn toward animals that produced less fat. A specially cultivated version of a nontoxic rapeseed crop gained popularity for its responsiveness to Finland’s climate and proved economically viable for oils and margarine for human consumption and as an animal feed. For years, this crop took over ever-increasing acreage, especially in southern Finland, although its yields began a decline after the turn of the twenty-first century, possibly because of warming temperatures.

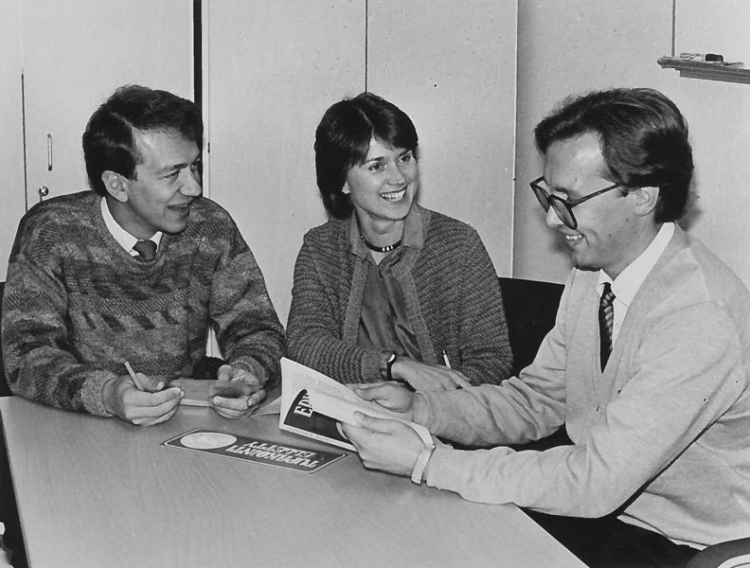

In the popular “Keys to Health” reality-TV–like show, ordinary Finns with raised risk of chronic disease were counseled to adopt healthier lifestyles and reduce their risk factors. Here, North Karelia Project Director Pekka Puska (left), nutritionist Pirjo Pietinen (center) and physician Kaj Koskela (right) are at work planning the show for the 1984-1985 series, which featured eight middle-aged, smoking North Karelians.

CREDIT: NORTH KARELIA PROJECT

The project even included an effort to turn Finns back onto the juiciest natural product of the land: its berries. An update on the “East Finland Berry and Vegetable Project,” which promoted berries and their juice to the people and motivated dairy farmers to switch to berry-growing, hasn’t been published since the 1980s. Nevertheless, the berry market in the country remains robust.

Stealth recipes

The men may have been fighting over fat or mulling the benefits of berry farming, but the women were quietly waging a new kind of war. Their role in the North Karelia Project was pivotal. Hearkening to the message of heart health shining in vegetable oil and a death threat lurking in butter, North Karelian housewives turned subversive. They mixed oil and butter, and their families apparently never knew the difference.

According to Puska and many others, women not only sneaked oil into the butter but also secretly diluted the full-fat milk they served their families. Full-fat milk in Finland is sold in red and white cartons, and North Karelian dinner tables were once laden with the “red milk.” After Puska and his team invaded the province, women began quietly thinning red milk to produce their own version of low-fat dairy.

A Finnish housewives organization known as the Marthas was a powerful force in changing the dietary habits of a nation. They liked Puska’s message and implemented it in their own homes and through educational outreach. Here, Marthas promote the healthful properties of mushrooms at the marketplace in the North Karelian town of Joensuu, in the 1970s.

CREDIT: MARTAT

Women had an existing network for disseminating their secrets: The Martat, or Marthas. The organization took its name from the biblical Martha, who worked to prepare food and lay a table when Jesus visited Martha and her sister, Mary. Biblically, Martha was busy “with many things” while Jesus spoke with Mary. The Marthas, whose symbol is a shapely, fluttering apron, have been busy since 1899 bringing the teachings of health and hearth to women.

In the 1970s, most Marthas were farmers’ wives, present in every village and municipality. Their power at the hearth was considerable, whether it was secretly adding oil to butter or slipping root vegetables into stews to make them healthier. As willing conduits of the project’s message, they “influenced eating habits and helped decrease the resistance of men,” says Vesa Korpelainen, who retired recently as head of the North Karelia Project’s successor organization, the North Karelia Center for Public Health.

After many years of affiliation with the project, Korpelainen is a trove of information, with a stack of local and national statistics at his fingertips. A big stack. By 1992, follow-up surveys for the effort showed that nationally, mortality from heart disease associated with blocked arteries had declined by almost 60 percent since 1972 — beating the decline predicted for successfully targeting all three risk factors. Cholesterol levels in middle-aged men fell by a fifth from 1972 to 2007 in North Karelia, and similarly elsewhere.

National saturated fat intake dropped by almost half from 1982 to 2007, and smoking prevalence fell from more than 50 percent among men in the 1960s to 17 percent in 2014. From 1971 to 2012, life expectancy for men increased by 11.6 years, from 65.9 to 77.5. And the countrywide 80 percent reduction in death rates from coronary heart disease between 1973 and 2013 rode down the steepest slope of all. Korpelainen notes that improved blood cholesterol probably explains about 40 percent of the decreased cardiovascular mortality in the province. By any measure, this would seem to be a war that Puska’s team had won.

On the eastern front

Korpelainen, who’s worked for decades in the former province (which, like all provinces in Finland, was abolished in 2010), readily spends a weekend day guiding a one-person tour of local homes, stores and farms to illustrate the positive consequences of Pekka Puska’s efforts. As his modest and well-used subcompact rattles its way down slushy main roads and frost-covered back lanes, Korpelainen points out the municipal healthcare centers in each town, centers that were established around the same time the North Karelia Project took off. One treasure from his information trove: This province in eastern Finland may be one of the few places on Earth where McDonald’s went to die. He proudly relates that the fast food franchise didn’t do well enough to stay open.

Shelves of low-fat “blue” milk and full-fat “red” milk in a North Karelia supermarket speak to the altered habits of Finns, who once favored the full-fat variety.

CREDIT: EMILY WILLINGHAM

Meanwhile, the supermarkets thrive, and the influences of the North Karelia Project are visually obvious. In the dairy section of one store, and in the filled shopping carts, “red milk” is clearly not the popular choice. The shelves of the low-fat “blue” milk stand almost empty next to full rows of red and white cartons. Finland’s Dairy Nutrition Council says that only 10 percent of milk consumed in the country in 2015 was whole milk.

But behind that clear visual lie some possibly ineradicable human predilections for fat and salt. A visit to the bakery shows wavering commitment to healthy whole-grain baked goods. Side by side with grain-laden, low-salt offerings are trays and trays of Karelian pie, a popular Finnish pastry packed with fat-saturated rice pudding or egg butter.

Out on store shelves, low-salt and low-fat offerings enjoy uneven success. Part of Finland’s campaign to improve heart health continues with package labeling. Consumers understand the meaning of a government-approved symbol of a red heart inside an incomplete red circle: Items bearing this logo promise food that is low-salt, reduced-fat, OK for the heart. Cheese packaging sports large-font numbers that reveal salt content. The shelves — some close to empty, some well-stocked — seem to communicate that people in Finland, despite messaging and heart symbols, may still like their cheese and bread a little salty (with the bread at least a little whole-grainy).

The statistics give a broader view. Finns are definitely eating more cheese, with consumption climbing by more than 60 percent from 2000 to 2016. That said, they are doing pretty well with their salt. The salt-reduction effort targeting both producers and consumers was yet another spoke of the North Karelia Project wheel and yielded a national average consumption decline of 40 percent by 2008.

Those reductions are another factor in the reduced hypertension rates in Finland: In the decades since this effort began, as salt intake fell, blood pressure dropped, too, by 10 mmHg, on average. Messaging alone wouldn’t have done it, researchers have concluded. The campaign needed what Puska included in the North Karelia Project: buy-in from a huge variety of stakeholders, including messages flogged in the news media.

And the butter? Now that the practice has long been legal, butter admixed with vegetable oil is a staple, and a popular one. National statistics show that Finland’s margarine or butter–oil mixture consumption outpaces butter intake by about three to one. What began with housewives secretly mixing oil into butter in the privacy of their kitchens is now a national practice.

Members of the housewife’s organization known as the Marthas, seen here in 1977. Unbeknownst to their families, Marthas would mix full-fat and low-fat milk to reduce their loved ones’ intake of saturated fat.

CREDIT: NORTH KARELIA PROJECT

One little pill

One stop on Korpelainen’s tour is the living room of the impeccably clean, light-filled home of the Riikonens in the forested municipality of Tohmajärvi. The Riikonen household was one of many in 1970s North Karelia that took Puska’s plan to their kitchen and table. Although Veikko worked in civil service for decades and Eila was a teacher, they have remained, like many Finns, quite close to the land. They offer koivunmahla, their distillation of sap and water collected from dripping birch trees, locally respected as healthy and curative. Also on hand is honey, harvested from bees that Veikko keeps, and although snow now blankets the land around the house, berries will burst forth with the spring.

Eila and Veikko were young parents when the project began, and they remember the “fat war” tensions. “The milk producers felt that their work was not valued,” Veikko says through an interpreter. “But it changed quite rapidly and even the farmers accepted the message.” The couple’s son, the current mayor of Tohmajärvi, experienced as a child the initial changes related to the North Karelia Project. He was not a fan, Eila says, of the sudden shift to low-fat milk.

Still, Eila and Veikko were ready adherents to the suggested dietary changes that they learned about from newspapers and radio, and they “tried to make changes and do as much as possible at home,” she says. They participated in one of the health surveys related to the project. They and their friends would talk among themselves about the program. Just as Puska and his colleagues desired, people were discussing cardiovascular health with friends and family, and in terms of prevention, not just cure.

And their children absorbed these discussions. When their son the current mayor was 5, his spontaneous greeting for a long-ago mayor, a smoker who was visiting their home, was, “By the way, you are not allowed to smoke here.”

Both Eila and Veikko seem convinced that these changes benefited them, too. Veikko’s father died at age 74 of a heart attack. Veikko, 75 at the time of the visit, says his own health is great. As proof, he takes out a copy of a recent medical report showing blood results. The numbers are good from a metabolic and cardiovascular perspective, and both Eila and Veikko seem fit, healthy and happy. His only struggle with food is to remember to eat it at regular intervals, a lifelong problem. His wife, it seems, is tired of reminding him, so he’s set alarms on his smartphone for midday reminders to eat lunch, which he proudly demonstrates.

And what does he eat? “Men want to eat meat,” Eila says. Veikko still does. His reasoning is that with all of his physical activity — beekeeping, chopping wood — he needs the dense caloric energy meat provides. His doctors, Veikko reports, say his health is like that of a 50-year-old.

But tucked away in his medical record is another note that might help explain Veikko's good cardiovascular health. On the back of his report is a list of pharmaceuticals he takes — just two. One is a statin, and the indication, according to the handwritten note, is “hypercholesterolemia,” or high blood cholesterol.

The cause-and-effect conundrum

That brief note in Veikko’s medical record represents one of the big challenges in definitively assessing the effects of the Finnish experiment so that the framework can translate into successes elsewhere: Changes unconnected to the project were also in play. After the war, those municipal health centers opened in the provinces, giving people greater access to care. The passing years also ushered in a new era of cardiovascular health, including the introduction of statins like Veikko’s in the 1990s, blood pressure drugs that had fewer side effects than older versions, and improved medical support to help people quit smoking.

Other factors outside of the project efforts were the social and technological conditions of the population of North Karelia in the postwar years and their gradual resolution, says Mikko Jauho, a sociologist at the University of Helsinki’s Consumer Society Research Center. The landscape changed in the borderlands after the war. It was a countryside in crisis on all fronts at the time, with an exodus of those who could leave — “The young people leave, the old stay,” Jauho says — and a sense of fatalism among those left behind, still nursing the nation’s battle scars.

You do not need to understand Finnish to savor the flavor of this early reality TV show, “Keys to Health,” that tried to steer regular Finns toward better lifestyle habits. The series may lack the energy of “Amazing Race,” the backbiting of “Real Housewives,” but there is vintage charm to these 1980s-era clips of Pekka Puska, fellow counselors and the volunteers, who jog through snow, sample nutritious meals, practice relaxation techniques and good-naturedly receive (a lot of!) advice.

CREDIT: YLE

Jauho has pored over hundreds of letters people wrote to project leaders in response to surveys, publishing his findings in a pair of papers. What led to the cardiac crisis in the eastern province? “People felt strongly that it wasn’t the fat, or it might be the fat, too, but it was structural change and all of the problems after the war,” he says. One correspondent expressed his own idea about what would solve the problem: “Give people work, and blood pressure will sink.”

North Karelia residents who were children at the time recall other changes to everyday life. Take one small, Finnish-language ethnographic study of 12 men who were boys when the project began. They are now middle-aged, and all but one of their fathers are dead, half from heart disease. A big shift they recall is the introduction of freezers into their homes, says study author and social epidemiologist Anne Kouvonen of the University of Helsinki. Freezers, she says, made it possible to preserve meats without salting them to death, and people could keep vegetables longer as well.

One strong skeptic of the methods of the North Karelia Project is Shah Ebrahim, an epidemiologist associated with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. In a 2001 editorial coauthored with clinical epidemiologist George Davey Smith of the University of Bristol, he essentially asked if the improvements were really attributable to the intervention. The pair noted that even as cardiovascular death rates declined from 643 to 118 per 100,000 men ages 35 to 64 in North Karelia, they also dropped like a stone from 1970 to 1985 in the comparison province, Kuopio, where no intervention was being conducted during the early phase. The decline in Kuopio was even steeper than in North Karelia, and rates also fell nationally. And, Shah says, “Other countries that did not invest in this sort of program experienced falls in cardiovascular deaths.”

Spreadable margarine in a North Karelia supermarket bears a heart-healthy logo. Finnish laws and economic incentives used to favor butter — but that has changed, along with citizens’ preferences.

CREDIT: EMILY WILLINGHAM

When the North Karelia Project was on the drawing board, some experts had argued for a more rigorous design, says Evelyne de Leeuw, a professor of public health at the University of New South Wales in Australia. Their idea was something closer to a randomized controlled trial in which researchers attempt to winnow down anything that affects an outcome to a handful of variables. It may be that those experts had a point. Later community interventions examining the effectiveness of similar programs, some of them randomized controlled studies, failed to yield the anticipated reductions in cardiovascular diseases, Shah says. Instead, the only groups in these studies that saw a decline were those at highest risk — people who had high blood pressure or a high risk of type 2 diabetes, he says, and he strongly suspects that medications made the difference there.

Nevertheless, Shah calls the North Karelia Project “a milestone in the history of efforts to prevent cardiovascular disease,” noting that when it began, cholesterol-lowering drugs were unavailable, antihypertensives had deterrent side effects and even doctors smoked. Puska’s multi-pronged approach, says Shah, was “innovative and bold and paved the way for community action for the prevention of other diseases,” such as HIV/AIDS.

“It absolutely stands up as an international landmark,” says de Leeuw. “The Finns started the North Karelia Project from a socially and politically deeply felt need to deal with a significant burden of cardiovascular disease, but they managed to let it evolve into a much more substantial … natural experiment.”

Indeed, says Jauho, a key legacy of one of public health’s most famous community-based efforts was the introduction of the concept of “risk factors” into everyday language.

From public health maverick to parliamentarian

Puska, now a member of Finland’s Parliament, takes on the question of how much these changes are the result of his project without batting an eye. He discusses the issue while sitting in the cafeteria of Finland’s “little Parliament,” across the street from the more imposing and governmental-looking real Parliament, where MPs like Puska can settle when they’re not in session. He’s heard the criticism many times since the first critical salvo fired in 1973, an editorial in a scholarly medical journal that characterized the plans for North Karelia as a sort of “throw it at the wall, see what sticks” approach.

But he doesn’t find the question of which factors directly led to beneficial change terribly relevant. Puska notes that an international team worked on the effort’s meticulous planning, which, he says, belies any charge of a “kitchen sink approach.”

Pekka Puska, now a parliamentarian in his 70s, hews to a healthy lifestyle. This shot was taken in 2015.

CREDIT: LEHTIKUVA / MARKKU ULANDER

Now matured from young maverick physician into a sort of Nordic ideal of an elder statesman, Puska gestures at a pile of studies on the table, stacks of papers he has authored or coauthored, describing successful outcomes from the project. He readily notes that the project was not a randomized controlled trial and never could have been, so whittling away all influences to a single or a few critical factors is almost impossible.

Sure, he acknowledges, other elements may have played a role in the improvements his project tracked. But he’s convinced his team’s tactics were effective. Statistical analyses, he notes, indicate that two-thirds of those outcomes can be traced to changes in people’s cholesterol, hypertension and smoking habits, the exact three targets of the campaign. Beyond that, he says, “you can forever debate on the causality.”

The MP tells a favorite story: A bus driver in Helsinki, decades after the project began, stopped his bus when he recognized Puska about to get off. “Come here!” the driver shouted. The parliamentarian continues: “He said, ‘When I saw you I decided I’ll give up this,’ and he crushed a packet of Marlboros in his hand.” Puska’s passion beyond the project is obviously the people, and he seems to hold a special place for North Karelians.

“North Karelians are on the lively side,” he says, smiling. “We had a lot of fun.”

In the bright land of berries

In the middle of the fun were some farmers who needed pacifying. When full-fat dairy became a watchword for bad health and the dairy farmers initially rebelled, one substitute market suggested for them was berry growing. Once a staple on Finnish tables, the berry — lots of different kinds of berries — experienced a newfound popularity, resulting in the 100 or so berry farms that now dot the country’s landscape. And perhaps no one in Finland knows more about berries (or is happier to promote them) than Ismo Ruutiainen. He owns one of those farms, in Kitee, in what was North Karelia, and is a retired adviser to agricultural industry in the province.

Berries may seem like just another spoke in the rolling wheel of the North Karelia Project, but they’re a matter of national pride in Finland. Australia’s de Leeuw points out that this pride isn’t just an odd Finnish obsession. The refocus on berries “indicates a broad societal commitment to a culture of health,” she says, “that has inspired many others around the world.”

Sitting in his warm home full of visiting family and friends, Ruutiainen beams with that pride as he uses his laptop to show image after image of a luscious variety of the deeply colored berries that his homeland produces. His graphs and charts suggest a longstanding commitment to berry production in Finland, across a variety of crops, including strawberries, raspberries, blueberries and blackberries. Land area devoted to berry production seems to have peaked in Finland in the mid-1990s and early 2000s, but levels still remain well above where they were in the mid-1980s, when the Berry and Vegetable Project was launched.

Ruutiainen has just returned from a trip to the United States to visit berry farms up and down the Pacific Coast. The farms were fun, but he’s come back unimpressed with US food offerings in general. “No vegetables,” he says, “and so much meat.”

While Ruutiainen talks, his son Lassi is busy in the open kitchen, making beelines from stove to counter and back. And then the group is gathered around the dining table, eyeing a bright, autumn-colored array of foods the young man has made. Pumpkin and squash with pureed fruit and fresh herbs. A hearty salad of grain, greens and cherry tomatoes with a light creamy dressing. A mashed spring-pea spread for the homemade, whole-grain flatbreads. And of course, for dessert, berry mascarpone with a rich blackberry pastry. Even a carnivorous housecat, stuck outside in the snow, clamors to come in and partake.

Not satisfied with this presentation of Finnish food and hospitality, Eeva Ruutiainen, the young man’s mother, calls for a small bowl of Arctic berries, poster fruit for the nation, for their American visitor to try. The obliging chef brings the golden seedy sour berries to the table, having warmed a frozen sample in the microwave. He’s clearly in charge of this kitchen, knowledgeable and savvy about seasonal flavors and the satisfying presentation of the healthy, meat-free meal he’s prepared for the assembled guests.

And his mother, Eeva? Rather than cooking, she sits and enjoys the food with everyone else. After all, she’s been busy all week waging war against cardiovascular disease at the North Karelia Center for Public Health, the successor to the project Pekka Puska began more than four decades ago.