The tussle over cigarette warning labels, and the hazy future of vaping

Regulatory hurdles, industry objections and legal fights have gone on for decades over traditional tobacco. What’s in store for the next generation of smoking?

Support sound science and smart stories

Help us make scientific knowledge accessible to all

Donate today

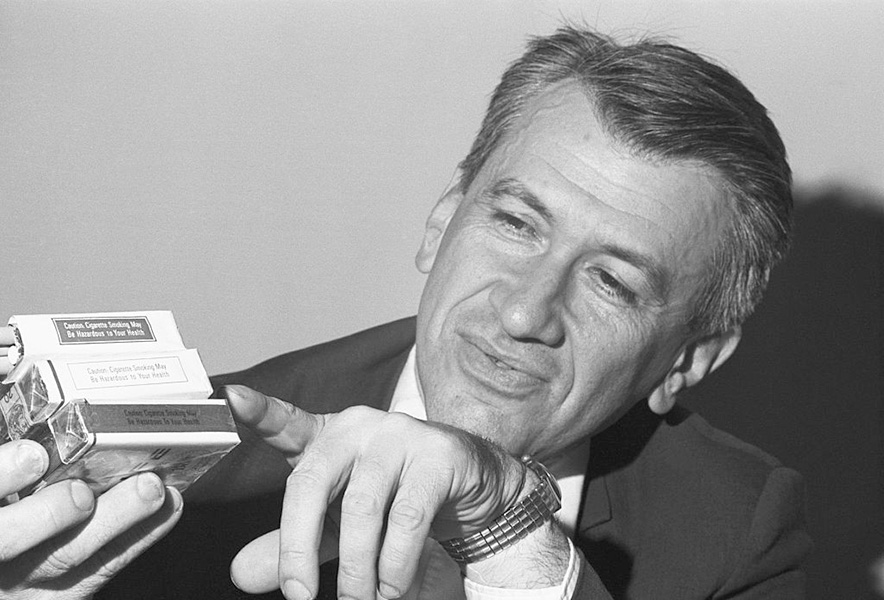

In 1966, the first warning label appeared on the side of cigarette packs in the United States. Stating “Caution: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous to Your Health,” it was also the first such warning for tobacco in the world. The message had been watered down from what was originally proposed, due to much political pressure from the tobacco industry, and the labels haven’t changed much since; they were last updated in 1984. New, more graphic designs created in 2020 have not yet been released, held up by legal challenges.

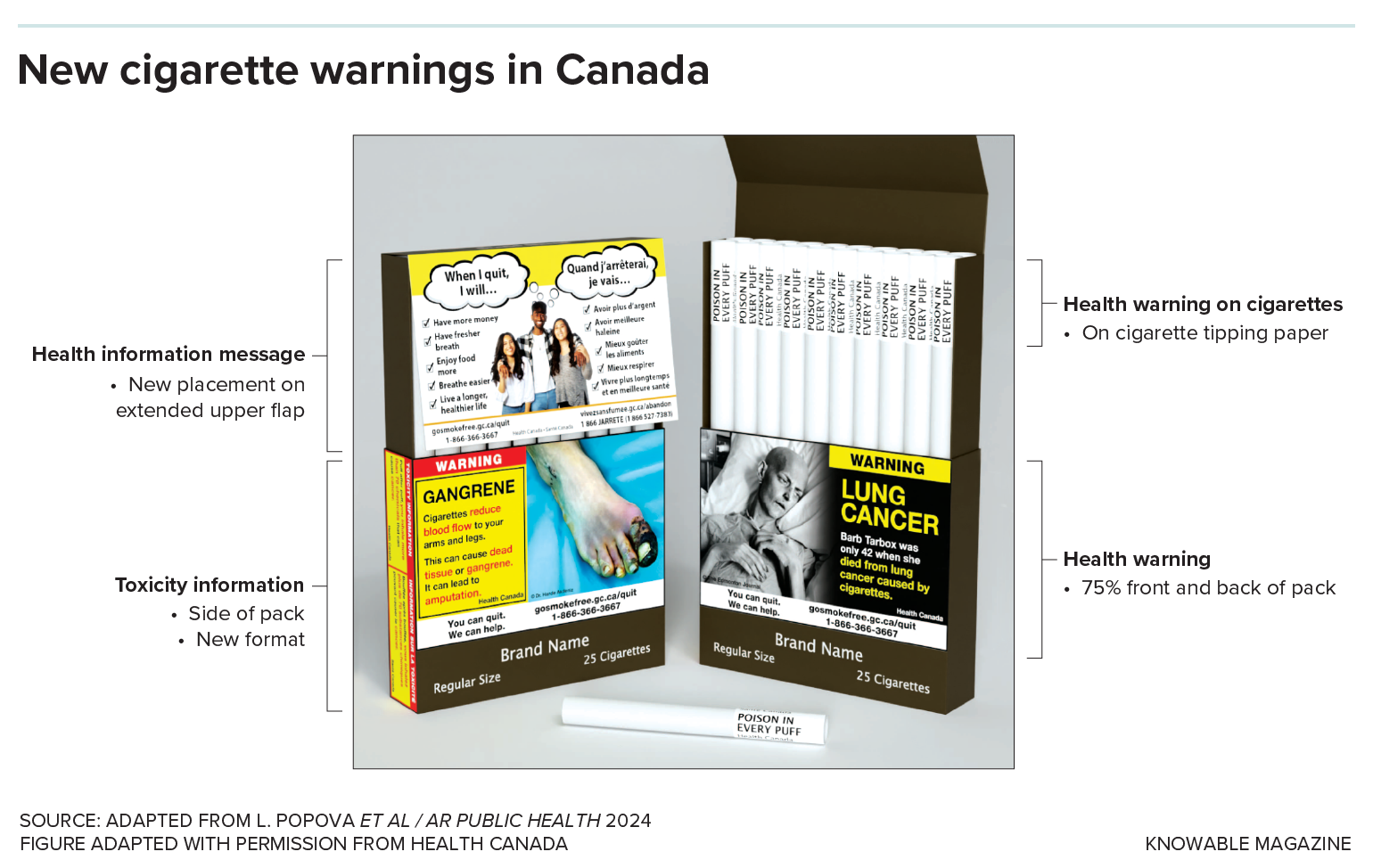

Many other countries have gone on to add graphic, full-color warning images, for instance of decaying teeth, gangrenous toes and patients dying of lung cancer, to cigarette packets, as well as explicit statements around the negative health effects. Countries have also enlarged those labels so they now mostly cover cigarette packs, added toll-free quit-line numbers to connect smokers to support services, and moved to plain, branding-free packaging. In April, Canada became the first country to put health warnings on individual cigarettes.

Despite these warning disparities, smoking rates have steadily dropped around the world since the 1990s due to a raft of tobacco control policies — not just warning labels but other measures too, such as tobacco taxes and bans on smoking indoors or in public places. As recently as 2021, 11.5 percent of Americans aged 18 and older smoked cigarettes, as well as 11 percent of Canadians aged 15 and older. It’s difficult for researchers to disentangle the real-world effects of cigarette warning labels because tobacco-control policies are often introduced as a whole package.

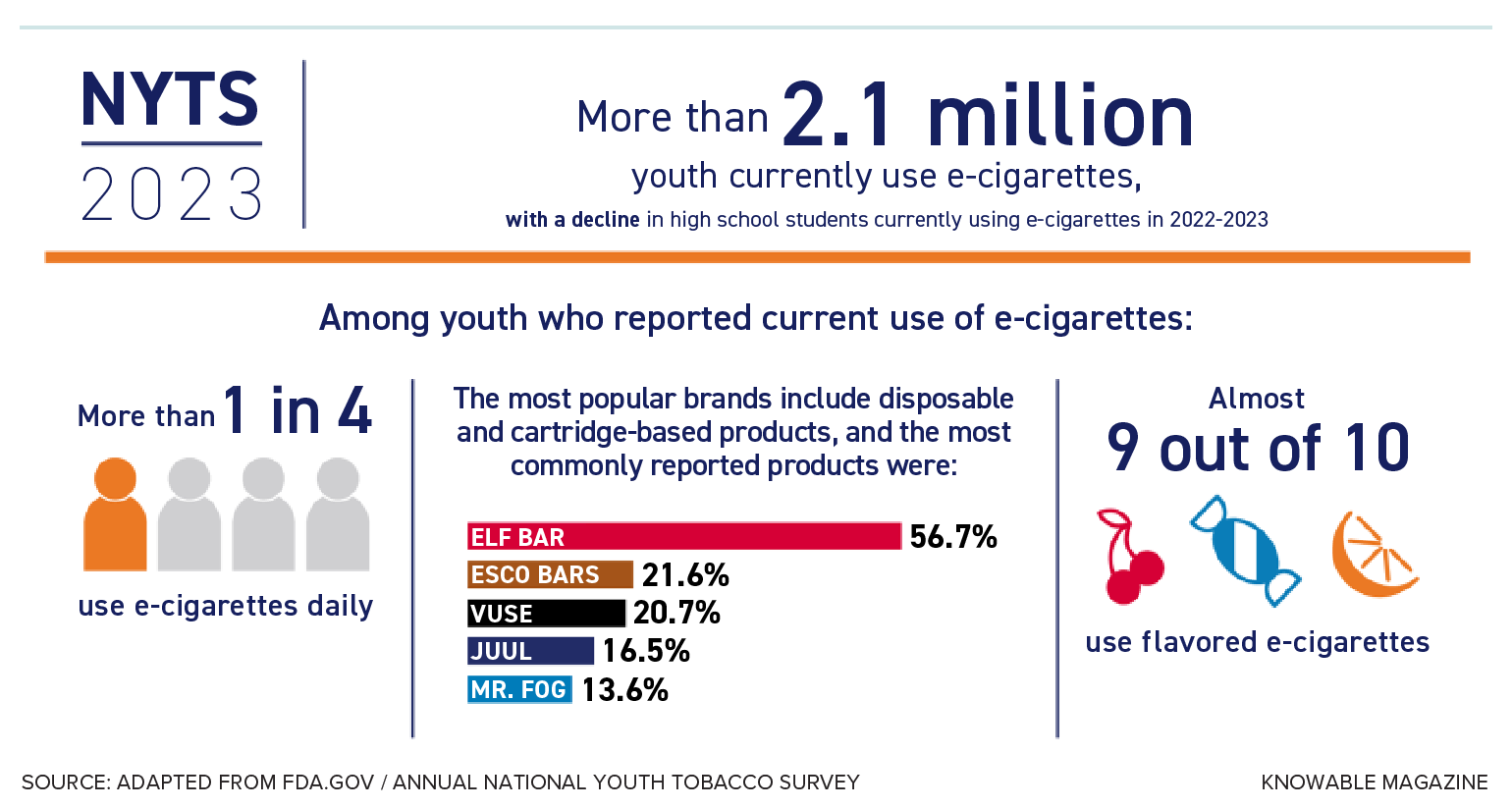

Over the last decade or so, a new public health challenge has emerged: e-cigarettes. Marketed as tools to help smokers quit, these devices aerosolize often-flavored liquids along with nicotine. Evidence around the short- and long-term health effects of vaping is still evolving but, concerningly, data suggest that youth who vape are more likely to start smoking. More than 40 countries have banned the sale of e-cigarettes, and many more restrict their use and regulate sales, especially to minors.

So far, the only warning labels introduced for e-cigarettes warn of nicotine’s addictiveness. But increasing e-cigarette use has health-policy analysts, behavioral scientists, epidemiologists and communications researchers asking whether warning labels could help to curb vaping.

To learn how effective cigarette warning labels have been in helping to reduce smoking, and what measures are likely needed to curb the epidemic of youth vaping, Knowable Magazine spoke with health communications researcher Lucy Popova of Georgia State University, coauthor of an article about warning labels in the 2024 Annual Review of Public Health. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start by talking about cigarette warning labels. Why does the US lag so far behind the rest of the world in its implementation of stronger, larger warning labels for cigarettes?

Originally, the US did try to go for the most striking images, like the rest of the world. This is how warning labels work. You show alarming pictures depicting the health harms of cigarettes on the packs, and smokers are more likely to notice them, think about them and remember them.

But a legal saga that’s been going on since 2009 has delayed their implementation in the US. In 2009, Congress gave the US Food and Drug Administration a directive to create pictorial warnings for cigarettes. Those were supposed to come into effect in 2012, but tobacco companies sued. In one case, the judge ruled that pictorial warnings weren’t purely factual; that the images were emotional, and people could misinterpret their meaning.

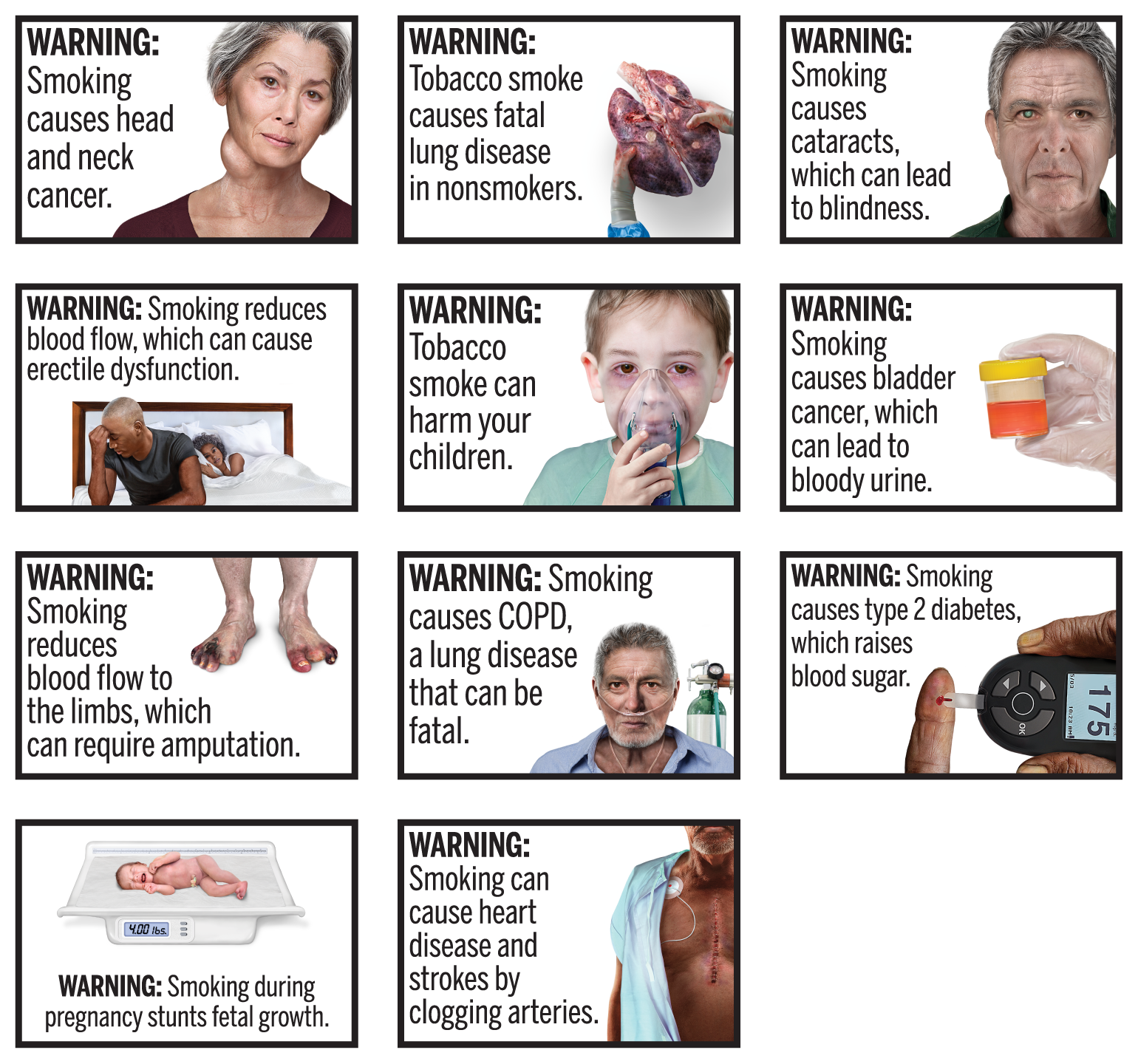

Graphic warning labels are designed to communicate information in a memorable way, and you cannot divorce information and emotion when you talk about smoking causing cancer. Still, the FDA agreed and said they would come up with more factual pictures. It took them eight years, but in 2020 they finally did. Those new warnings, a set of 11 labels, were slated to appear on cigarette packs in 2021, but again, tobacco companies sued, arguing that the First Amendment means the US government cannot compel companies to say things they don’t want to say.

In March this year, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that the FDA’s labels are, in fact, consistent with the First Amendment and can be mandated. These labels include colorful images showing the harms of smoking, and would bring the US in line with many other countries.

But when the new labels will appear on cigarette packs is uncertain. There are a few pending legal claims that the court still needs to decide on, and the eventual rulings will likely be appealed. So we’re still in the same holding pattern to see if cigarette warnings will finally be updated in the US for the first time in 40 years.

Cigarette warning labels in the United States have not changed since 1984. Legal challenges by the tobacco industry have held up the implementation of new graphic designs created in 2020, shown here, but a recent court ruling may bring their rollout closer.

CREDIT: FDA.GOV

What about other countries? Has the tobacco industry had the same influence there?

Basically, any efforts to strengthen cigarette warning labels have been met with legal challenges from the tobacco industry. So far, most countries have succeeded in defeating those challenges. Unfortunately, even the threat of legal action creates delays, because lawmakers might take longer to prepare their policies to make sure those policies can withstand challenges in court. That was the case with the FDA; that’s why they took eight years to come up with a second set of warning labels. In the meantime, tobacco companies continue selling their products.

What evidence do we have that warning labels actually work to deter smokers or curb smoking rates?

There’s quite a substantial body of evidence, ranging from lab studies to observational, population-level studies. Lab studies are controlled experiments that randomize people into groups and show them different warnings, or give smokers cigarette packs with or without warning labels. If we see a difference between the groups, we can be quite confident in attributing this difference to our intervention, the warning labels, because people are randomized.

What’s missing from those studies, however, is how those labels impact behavior in the real world.

We do have a lot of studies, though, where researchers looked at the effects of policy changes. So when countries such as Canada introduce larger or more colorful warning labels and other countries like the US don’t, we can do cross-country comparisons and find that, yes, indeed, warning labels work — in most cases.

Occasionally, those studies don’t find effects. But as a whole, research shows that when smokers see cigarette warning labels, they think more about harms, perceive cigarettes as more harmful, think more about quitting, and it does change behavior; they do try to quit. Or, they might put out a cigarette earlier because they’re looking at the pack and thinking, “I’m damaging my lungs right now.” And that can eventually lead to smoking cessation.

New warning labels on cigarette packs and individual cigarettes in Canada. They began coming into effect in 2024, for king-size cigarettes. The rollout will continue in 2025.

It’s much harder to find data on initiation rates, on people who would’ve otherwise started smoking but didn’t. And it’s hard to argue that the reductions we see in smoking rates is because of warning labels. Countries usually pass a whole package of policies — not just warning labels: increasing taxes and strengthening policies on smoke-free places at the same time. They might run education campaigns about how harmful smoking is. Or individual provinces in Canada, for example, passed their own laws to ban flavors such as menthol before the federal government did. And you do see smoking rates going down but you don’t know what measures were the cause. In total, the evidence indicates warnings on cigarette packs are effective when used with other policies, and all the policies working together is definitely better than one.

What happens to the effect of warning labels over time? Does their effect wane and if so, what have countries done to counteract this?

It definitely does wane. People get desensitized. You see an image again and again, and after a while, it no longer bothers you. So countries develop whole series of graphic warnings and the World Health Organization recommends rotating them. But tobacco companies argue that they can’t rotate them quickly, that it’s not economical to change their packaging.

Confronting people with scary images about health harms isn’t the only way warning labels work, though. Putting large warning labels on cigarette packs also makes the product less attractive. Some countries, such as Turkey, Benin and Nepal, have warnings that cover 90 percent or more of cigarette packs. So from the standpoint of making the pack less appealing, bigger warnings do serve that purpose.

In the case of Canada adding warnings on individual cigarettes, the idea is to keep reminding smokers each time they pull out a cigarette of the harms of smoking. The more exposures you have to the message, the more it’s going to sink in.

If countries have to keep revising their warning labels so they remain effective, will this continue until warning labels cover practically the whole pack and every cigarette? Will warning labels eventually reach their limit — and what happens then?

That’s why warning labels are just one of the many policies that work towards what scientists and policymakers call “the end game” — that is, having less than 5 percent of all groups and the population smoking tobacco. Warning labels are not the only thing that’s going to get us there; it’s a bunch of other policies.

New Zealand, for example, passed laws in 2022 to raise the legal purchasing age of cigarettes annually, which would have led to the first smoke-free generation. Those laws were meant to take effect in 2027 and the age limit would have risen each year so that some people simply never reach the age where they can legally buy cigarettes, and after a time, it becomes illegal for everyone. But the new government repealed those laws earlier this year. The UK passed a similar bill in April 2024.

New Zealand was also looking at reducing the amount of nicotine in cigarettes to non-addictive levels so it’s easier for people to quit and harder for them to get addicted. That would have been quite a game-changer, and we’ll see if that happens in other countries. The US has been considering this policy; it’s been on the FDA’s docket for two years.

Again, cigarette warning labels will help along the way. They de-normalize tobacco, reminding people of the long-term health effects and that this is not a safe product — it kills half the people who don’t quit.

What does the history of cigarette warning labels tell us about health warnings for e-cigarettes? What are the challenges you foresee there?

In the 1960s, when the first cigarette warning labels were introduced in the US, we had a really big body of evidence showing all the negative health effects of cigarettes, such as the fact that smoking causes cancer. And even then, with all that evidence, we weren’t able to put strong messaging on the packs.

The first health warning on a cigarette pack was rolled out in 1966, in the United States. In this historic photo, Dr. Daniel Horn, director of the Public Health Service’s National Clearinghouse for Smoking and Health, shows off the new warning. Horn’s research had linked cigarette use to cancer.

CREDIT: BETTMANN / GETTY IMAGES

With e-cigarettes, because they’ve been around for only a short time, we don’t have this overwhelming body of evidence showing their negative health effects. We know they irritate the lungs and affect the cardiovascular system, and that they contain nicotine and harmful chemicals — sometimes at higher levels than in cigarettes.

Most countries — probably with one eye towards potential legal challenges — have so far put warnings on e-cigarettes that just deal with the nicotine, informing people that these products contain nicotine and nicotine is addictive. We haven’t seen much resistance from tobacco companies about the warning labels on e-cigarettes, mostly because it’s hard to come up with something more benign than “nicotine is an addictive chemical.”

Communicating addiction is much harder than communicating about harms, because people don’t think it applies to them. Most people, when they start smoking, think they are only going to smoke a bit. Our research shows that people generally recognize the harms of smoking and appreciate they might get cancer. But when you ask them about addiction, they say, “I’m not going to get addicted. I’m the one in control.” So this warning, that e-cigarettes contain nicotine and it’s addictive, doesn’t dissuade people from vaping. And that’s partly why we haven’t seen much pushback from tobacco companies.

One of the other challenges is the debate over whether we should be careful in communicating about the harms of e-cigarettes because e-cigarettes might be an “off-ramp” for adult smokers who cannot otherwise quit, helping them switch to less harmful products. But from what we’ve seen so far, e-cigarettes have had such an oversized impact on youths, as opposed to helping smokers quit.

Statistics from the United States’ National Youth Tobacco Survey from 2023. Vaping and other tobacco use decreased from 2022-2023 among high school students, but a similar decrease was not observed among middle-school students. Overall, 7.7 percent of youth (2.13 million) use e-cigarettes.

Some smokers do switch to e-cigarettes and that might be good for them, but a lot don’t, and many people become dual users. Researchers find that in controlled lab studies, e-cigarettes help smokers quit, but this is a tightly controlled environment where smokers also get behavioral therapy and receive support.

In the real world, most studies show that e-cigarettes don’t help people quit smoking. And now we’re faced with this epidemic of kids vaping. With e-cigarettes, people just carry them in their pocket, they use them all the time, and that creates way higher levels of addiction. So some people find them harder to quit than cigarettes.

Another challenge is lobbying. Tobacco companies tell governments e-cigarettes help smokers quit — even though none of them applied for that approval pathway, in the US at least. In the US, companies can apply for any product to be considered a smoking cessation tool if they can show evidence that they do in fact help in that way. But despite the industry’s lobbying messages, no company has gone down that route yet.

Can warning labels on vapes really be effective if we don’t fully know what the long-term health impacts are?

As the evidence evolves, governments, guided by health advisory bodies, will have to decide at what point we have enough information to put warning labels on e-cigarettes, about specific health effects. And they might not even be needed. Research shows messaging about harmful chemicals in a product is very effective too, because people are really good at connecting the dots. When they hear about harmful chemicals in e-cigarettes — like formaldehyde — they jump straight to thinking it’s going to badly affect them, and they don’t want to use those products. So that might be the way to move forward with more effective warnings earlier on.

But there are so many ways to address the problem of youth e-cigarette use. The US has mostly been running educational campaigns, such as the Real Cost campaign. When we talk to kids in our studies, they tell us they see those ads, they remember them, and they recognize vaping has all these harms. So warning labels aren’t the only thing that will work.

And from a cost-benefit perspective, it takes a lot of effort to put a new warning label on a product. It’s definitely worth doing, but at the same time, resources might be better spent on very effective educational campaigns.

This short video from the FDA’s Real Cost Campaign aims to deter youth from vaping by informing them that cigarettes contain formaldehyde.

CREDIT: THE REAL COST

Are you optimistic that these policies, educational campaigns and possibly warning labels for e-cigarettes, will work?

It’s easy to be pessimistic when you see the resistance from the tobacco industry to public health policies. But at the same time, you have to remember how far we’ve come. I remember people smoking on airplanes, when smoking was much more accepted, whereas today smoking rates are under 10 percent in countries such as Australia, Peru and Sweden. So we are getting there. The tobacco industry is not going away; it will probably morph into something else. But I am optimistic that smoking rates will continue to drop.

As for e-cigarettes, the future will show us how effective policies are.

If you were in charge, what strategies aside from warning labels would you recommend to reduce the harms of vaping?

One thing is to actually regulate the production, distribution and sales of e-cigarettes, because we don’t know what’s in them. And getting rid of all the flavored tobacco, and flavored e-cigarettes, that would be a big step. If there were no flavors, there would be a lot less smoking and vaping.

We could also use influencers on social media to promote being tobacco-free, in the same way that tobacco companies have used influencers to promote their products. We know that works; they influence kids. We need to stay one step ahead of the tobacco industry on e-cigarettes — or, at least, not fall too far behind.

10.1146/knowable-082124-1

TAKE A DEEPER DIVE | Explore Related Scholarly Articles