A mother’s milk, rich in an exquisitely tailored mix of fats, proteins, vitamins and minerals, provides all the nutrition a helpless infant requires — and more. Breast milk is thought to protect against disease, set up a healthy digestive system and even influence a child’s behavior. And yet we know a lot less about this important substance than we could, says lactation researcher Katie Hinde of Arizona State University.

In a 2016 talk, Hinde noted that more studies are done on coffee, wine or tomatoes than on human breast milk. (The scholarly database Web of Science identified about 1,200 scientific articles published in 2017 for the search term “breast milk,” compared with almost 3,500 for “tomatoes.”) “Breast milk,” Hinde says, “has not been a research priority.”

But the research is picking up. Here are five mysteries about breast milk that scientists are working to understand.

Nursing sick babies

It’s well-established that human milk (as well as the fluid known as colostrum that mothers produce the first days after birth) carries protective factors such as antibodies to help a baby stave off infections. But research suggests that immune components in milk might ramp up when babies need them most. A 2013 study found that when mothers and babies both had colds, levels of white blood cells in milk jumped by a factor of 64. But even when just the babies were sick, levels of white blood cells still increased 13 times. “That’s quite a big increase,” says the study’s lead author, Foteini Kakulas (formerly Hassiotou), a cell biologist and lactation researcher at the University of Western Australia.

Research suggests that immune components in milk might ramp up when babies need them most.

A second study found that lactoferrin — an immune molecule that performs a variety of protective functions, such as puncturing the walls of harmful bacteria — was elevated in the weeks before and after an infant was sick. Once again, mothers did not report being sick, though the authors write that there was “almost certainly” underreporting of illness from moms.

How might this work? The most likely explanation is that infant saliva traveling back through the mother’s breast ducts carries a status report on the baby’s health, says Kakulas. “When baby saliva is transferred back into the breast … it’s very logical that the pathogen that is driving the sickness would be transferred too.”

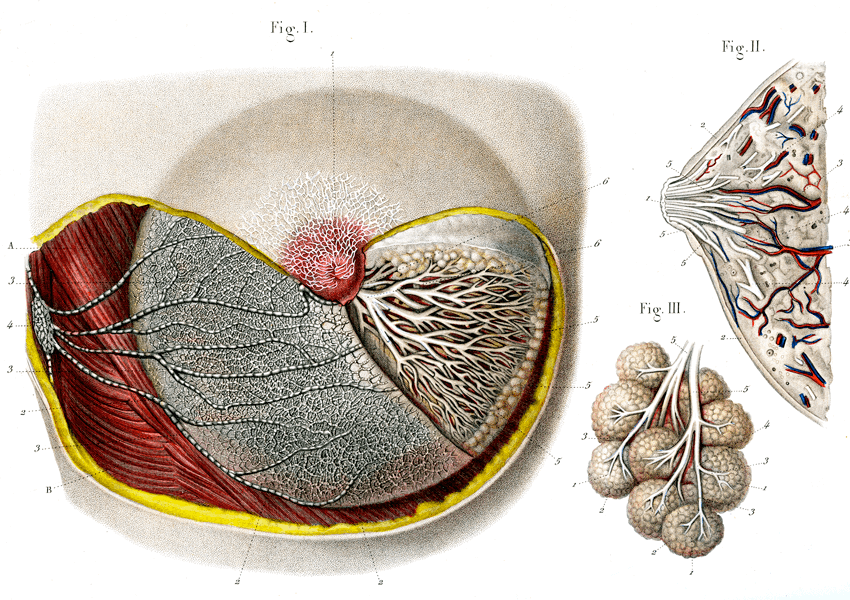

These 19th century illustrations hint at the internal workings of the breasts. Milk is made and stored in the alveoli, depicted as clumps of white spheres. Branching milk ducts carry milk from the alveoli to the nipple. Lymphatic vessels (on the left, in Figure 1) also lace through the breast tissue, carrying fluids and cells.

CREDIT: COLLECTION ABECASIS / SCIENCE SOURCE

Sleep signals in milk

As new parents know well, babies don’t come with built-in sleep schedules. Could breast milk help to set them? Both the sleep hormone, melatonin, and its precursor, tryptophan, are present in human breast milk and both seem to fluctuate on a cycle that might help babies sleep or wake. A 2016 study found that melatonin levels were, on average, nearly five times higher in breast milk produced at night than during the day.

Another report, in 2017, found that levels of the hormones cortisone and cortisol were higher in morning breast milk than in milk produced in the afternoon, evening and night. Both cortisone and cortisol are involved in the body’s stress response, and cortisol serves to kick-start our physiology when it’s time to wake.

But it still isn’t clear whether these signals actually allow a mother’s daily rhythm to shape her baby’s sleep-wake cycle, says Hinde. Also unclear is what a lack of these chemicals might mean for formula-fed babies, or what may happen to sleep patterns if babies drink milk pumped at another time of day. “We know that babies have the receptors for these hormones in their bodies, that the hormones coming from the mother are binding to receptors in the baby,” she says. “But what does it mean if they aren’t getting that signal? We don’t know.”

Eating for the gut microbiome

Breast milk isn’t food just for babies — it’s food for trillions of microbes that set up camp in their digestive systems, a community dubbed the human gut microbiome. Recent research suggests that breast milk may have evolved to promote the growth of microbes that help keep babies healthy.

Breast milk isn’t food just for babies — it’s food for trillions of microbes that set up camp in their digestive systems

“The third-largest constituent in breast milk is not there to feed the babies — it’s there to feed the microbes,” says microbiologist David Mills of the University of California, Davis. He’s referring to human milk oligosaccharides, complex chains of sugars found in breast milk. (Mills has established a probiotic company based on his research.) These complex sugars bolster the kinds of intestinal bacteria that can digest the compounds into short-chain fatty acids — ones that babies need to thrive.

It’s not yet clear what defines a healthy infant gut microbiome, or how that system changes as babies develop. And scientists disagree on how the microbiome is set up to begin with: Are key microbes delivered to the newborn’s uncolonized gut via breast milk, or do they come in from other sources such as amniotic fluid or the mother’s skin?

Variations in milk

All breast milk is not created equal: It can vary in levels of proteins, fats, sugars, hormones and other components. But breast milk doesn’t just differ from mother to mother. It can also differ when the same mother nurses different babies, and across the span of an infant’s development.

It also may shift depending on a baby’s sex. Working with rhesus monkeys, Hinde found that that mothers make more milk for female offspring, but milk richer in fat for male offspring. She saw similar sex differences when she pored over the lactation records of more than a million cows.

If these kinds of differences translate to human milk, understanding them could help optimize formula or donor milk for babies who don’t have access to their own mother’s milk, Hinde says. But scientists have only begun to characterize this variation and the factors that drive it.

A dash of stem cells

In 2007, scientists discovered an unexpected ingredient in human breast milk: stem cells. These cells retain flexibility that most adult cells have lost and can form a broad variety of tissues. In a 2014 study, scientists tracked individual stem cells from the mammaries of nursing mice. They found that the cells crossed the pups’ stomach walls into circulation and lodged themselves into developing tissues throughout their bodies. When the baby mice grew up, the mothers’ cells were still there and had turned into mature tissues alongside the babies’ own cells.

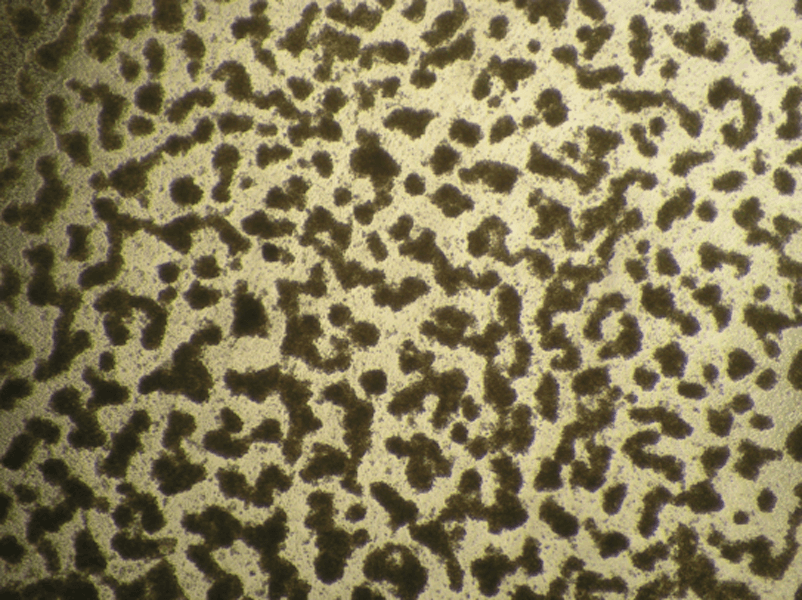

Stem cells extracted from breast milk take on their own life in the laboratory, forming organ-like blobs reminiscent of the breast’s milk-producing alveoli. Like alveoli, these lab-grown organoids can make milk.

CREDIT: F. KAKULAS / INFANT JOURNAL 2015

In a lab dish, scientists have grown stem cells extracted from human breast milk and coaxed them to form organ-like blobs that have spherical endings reminiscent of the alveoli that make up the mammary glands. These organoids could even produce milk.

No one yet knows how these cells affect infant development or what happens to babies who don’t get them — another mystery to add to the things-we’d-like-to-know list.