Bringing the hospital into the home

A movement to provide hospital-level care for sick patients in their own beds, in the comfort of familiar surroundings, is growing in the United States — a trend already embraced in some other countries

Support sound science and smart stories

Help us make scientific knowledge accessible to all

Donate today

A while back, Robert Diegelmann completed a 10-day hospital visit — in the comfort of his home.

The 81-year-old was being treated for a recurring infection at VCU Medical Center’s brick-and-mortar hospital in Richmond, Virginia, when his doctor suggested he finish his hospital stay at his home in Midlothian, some 15 miles away.

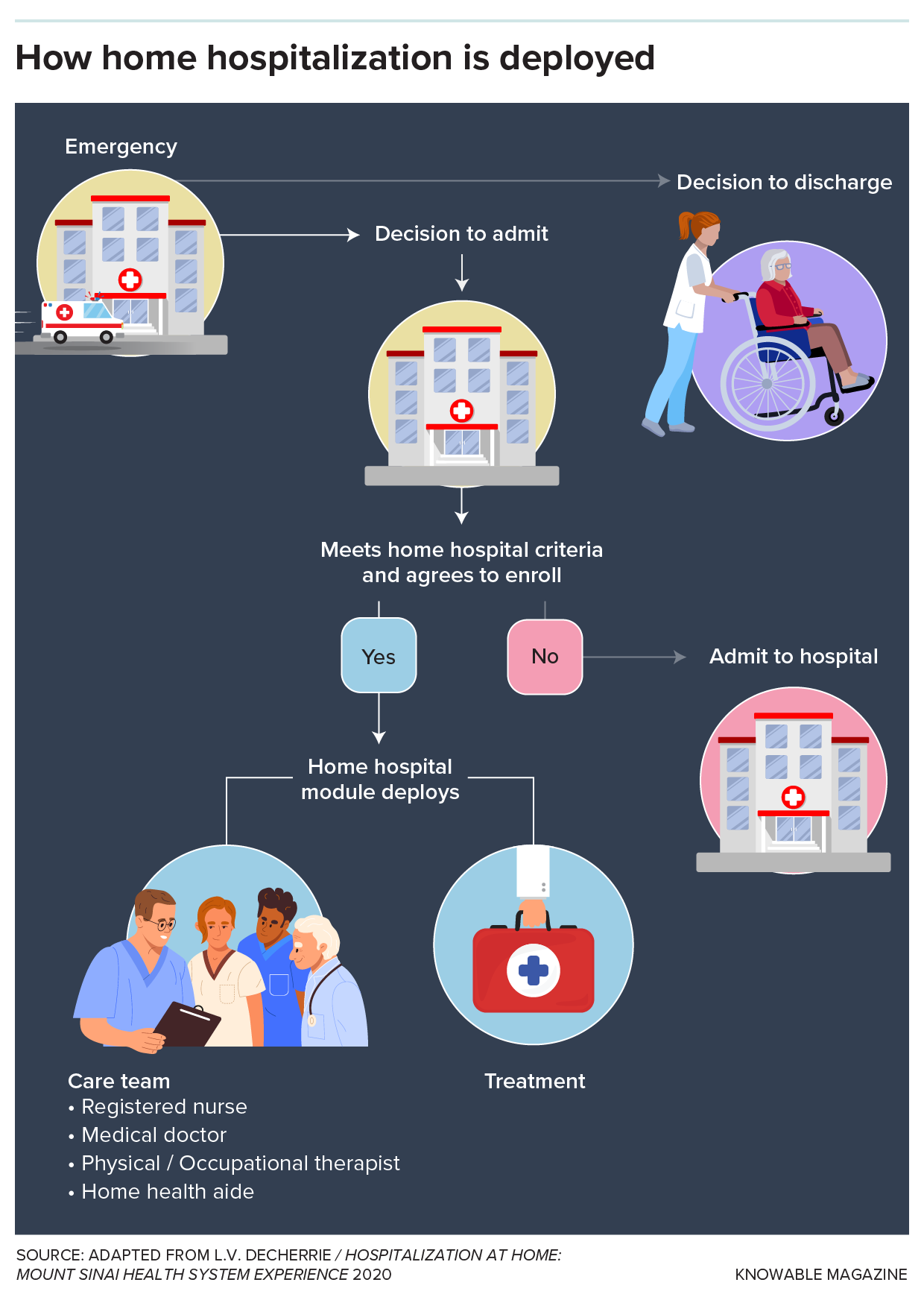

The medical center arranged his transportation home and supplied meals. Nurses visited twice a day, and twice a day by video, too. A courier delivered daily medications to his house. His vital signs were monitored remotely, and he had round-the-clock access to a clinician via phone call or text.

“Every day or so, a physician would get on the screen, and we would talk back and forth, and he would answer any questions I had,” says Diegelmann, a retired biochemistry and molecular biology professor. “It was exactly like being in the hospital, but much more comfortable.”

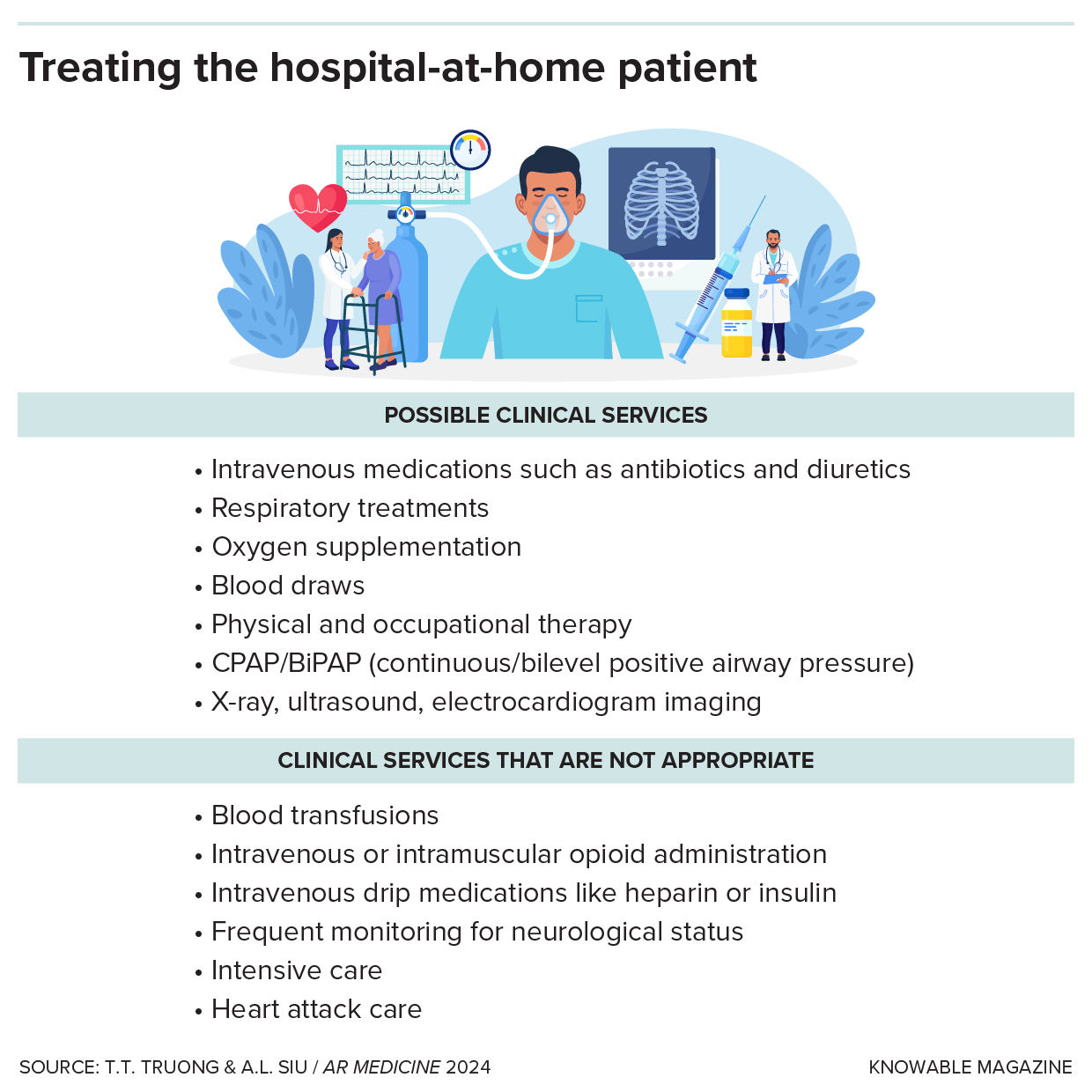

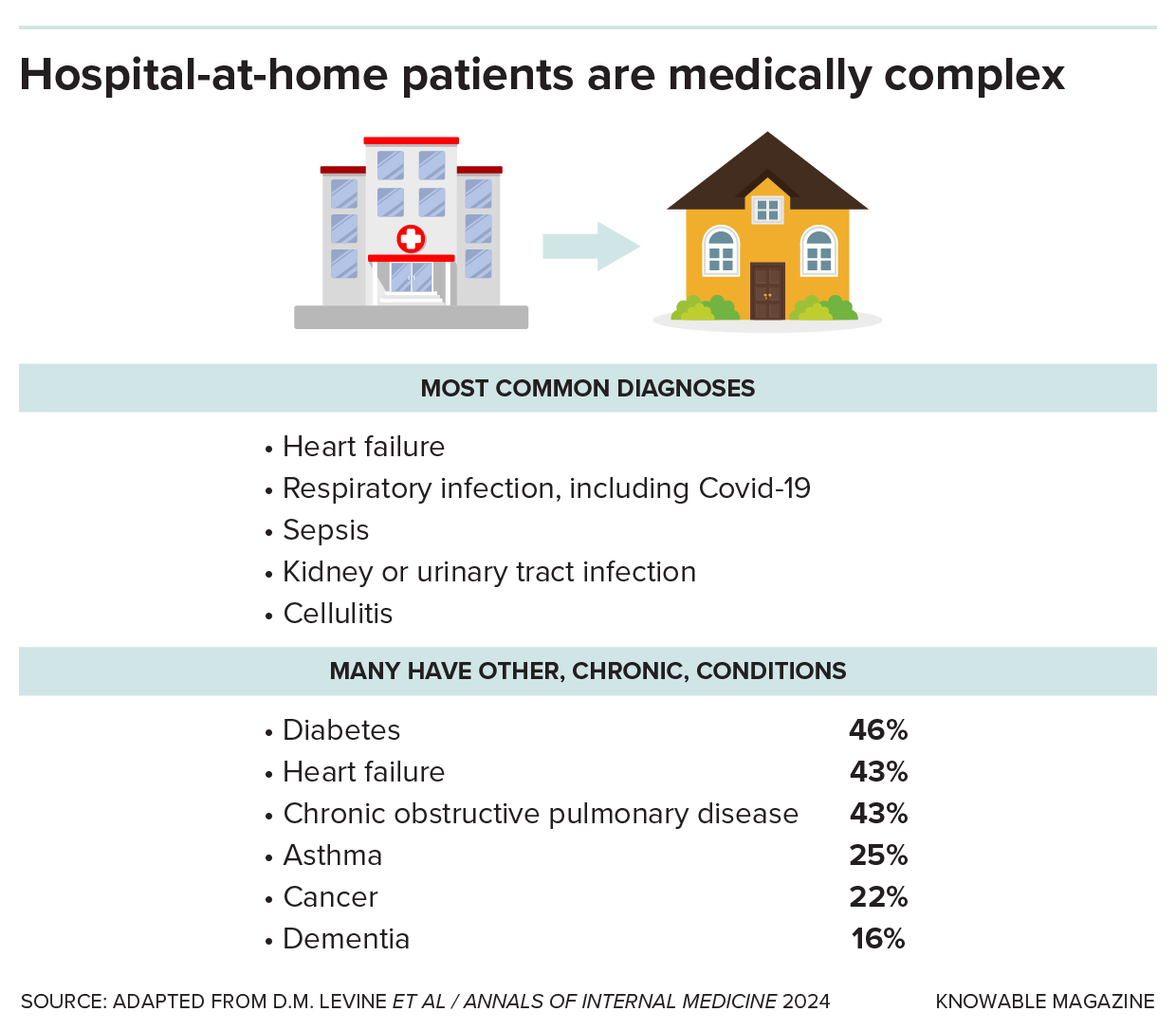

Like Diegelmann, tens of thousands of hospitalized patients across the United States have been treated in their own homes as the hospital-at-home movement, widely used in some other parts of the world, gains traction. These home hospitals provide many of the services patients get in physical hospitals: X-rays, physical therapy, respiratory therapy, intravenous treatments, blood draws for laboratory analysis and more. They provide supplies and equipment, such as hospital beds and specialized mattresses. Adults with a range of diagnoses, such as respiratory infections, heart failure, sepsis, pneumonia and pulmonary disease, are deemed eligible.

It’s a trend that took off in the 1990s in Australia and Europe, and — post-Covid — is growing in the United States. In the last four years, more than 350 hospitals have been authorized to offer hospital care at home, with more being added steadily. Some intend hospital-at-home to become a major element of their operations: Boston’s Mass General Brigham, for example, says it expects 10 percent of its inpatient care will shift to its home hospital program in the next few years.

Many — but not all — common hospital services can be delivered in the patient’s home.

“Imagine you’re in the emergency department about to get wheeled to your room and instead you’re taken to your own bed with your own clothes, family around, your dog next to you, your privacy,” says Julia Siegel Breton, co-medical director of Hospital at Home at VCU Health. “No beeping, no 4 a.m. lab draws, no people coming in and out all the time, no bright lights.”

Medicare, the biggest insurer in the United States, has been paying health systems for hospital-at-home care since the pandemic, but without a promise to continue indefinitely. Advocates are hopeful that Congress will extend support for such programs for another five years and believe this will trigger the robust research that’s needed to make hospital-at-home commonplace in the United States.

Easing the load on hospitals

Some of the first hospital-at-home programs started in Australia, where patients with certain medical conditions have been hospitalized at home since 1994, when the Victoria state government was under financial stress.

“Some smaller hospitals were being closed,” says Michael Montalto, who served as the first medical director for a hospital-at-home service in Australia. “And this was seen rightly as a kind of pressure release valve that might allow hospitals to respond to demand without the necessity of bricks and mortar, which they couldn’t afford to build.”

In the decades since, hospital-at-home has spread across the country, and Montalto estimates it now accounts for almost 4 percent of admissions at Australia’s major hospitals. The idea has caught on in several other countries, including the United Kingdom, Spain, France and Israel, from a push to increase capacity to treat patients without building new hospital wings.

In hospitals that offer at-home care, patients are offered the option if they meet certain criteria, such as living within 30 minutes of the hospital and having a condition that can be managed in their home.

The first hospital-at-home trial in the United States, also in the 1990s, had different motivations. Geriatrician Bruce Leff and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore sought to improve treatment for homebound older adults struggling with health problems — people who needed hospital care but risked deteriorating in regular hospitals. It was a tiny pilot program serving 17 patients, but the research team’s analysis concluded it was “safe, feasible, highly satisfactory and cost-effective for certain acutely ill older persons.”

Other small experiments followed but, because Medicare and most private health insurance plans did not cover home hospitalization, the idea did not gain broad traction — until Covid-19. As the pandemic overwhelmed hospitals, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced in 2020 it would pay for home hospitalizations for two years. That was the break that hospital-at-home pioneers needed.

In New York, for example, the Mount Sinai Health System had launched its home hospital program in 2014, but until Medicare jumped in, growth had been slow. In 2024, the program treated about 1,000 patients for asthma, heart failure, pneumonia, dehydration, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and more. It plans to double that number in 2025, says Tuyet-Trinh (Trini) Truong, the program’s chief medical officer.

The reasons mirror those of Australia: Although the pandemic is over, America’s hospital capacity problem is not. For decades, hospitals have ratcheted down bed numbers as health care shifted to outpatient clinics. Now an aging population and high levels of chronic disease are creating demand for beds that no longer exist. In many cities, emergency department boarding — patients held in hallways for hours, even more than a day, while waiting for a bed — has become increasingly common.

“Just like any other big health system, especially in the city, we are always very, very stretched for beds,” says Truong, who wrote about the hospital-at-home movement in the 2024 Annual Review of Medicine. “And we are now part of the strategy to create more beds.”

The alternative, expanding or building new hospitals, is expensive. Major hospital projects routinely cost more than $1 billion, and one estimate puts the average cost of hospital construction at $500,000 to $1.5 million per bed.

Advocates say that home hospitals are particularly beneficial for some patients. Breton of VCU Health says that immunocompromised patients, such as people with cancer or transplanted organs, aren’t exposed to infections common in traditional hospitals. And patients with dementia may avert delirium, a common problem when routines are disrupted in traditional hospital stays.

For all these reasons, many American health systems are eager to get in on the hospital-at-home trend — yet are reluctant to take the leap. While more than 350 hospitals have been authorized to treat patients at home, some have not launched their programs, waiting for more clarity on how to proceed.

Patients hospitalized at home typically have serious chronic conditions in addition to the acute problem that requires hospital-level care.

What works best?

Despite the fledgling status of the hospital-at-home movement in the United States, there have been dozens of studies about it as US health systems and policymakers try to understand whether it is a good idea. But definitive answers to important questions remain: Is the care equal to that in traditional hospitals? Do home hospitals cost less? That’s because studies to date have been small, and programs differ from one another. “There is not yet a strict definition of ‘the best home hospital,’” Montalto says. “In fact, there isn’t any study comparing one home hospital model to another.”

The broadest research so far suggests that patients treated in home hospitals fare well compared to those treated in regular hospitals, and costs for home treatment may be lower. When the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reviewed the performance of 332 home hospitals authorized to treat Medicare patients, it found that home hospital patients had lower rates of mortality and hospital-acquired problems such as bedsores and urinary tract infections than similar patients treated in traditional hospitals. Feedback from patients, family members and caregivers was “overwhelmingly positive,” according to the government report.

Separately, researchers at Mass General Brigham, Harvard Medical School and Johns Hopkins University reviewed outcomes for more than 5,000 Medicare patients treated in home hospitals between July 1, 2022, and June 30, 2023, and found that, after discharge, they had low rates of mortality, relatively few hospital readmissions within 30 days, and limited use of nursing homes.

Studies of individual hospital-at-home programs have found that the care costs less than that in traditional hospitals. When researchers compared costs (including nonphysician labor, supplies, monitoring equipment, medications, laboratory orders, radiology studies and transportation) for 43 home hospital patients to those for 48 similar patients treated in regular hospitals, they found that the average cost for home hospital patients was 38 percent lower.

Not everyone’s on board

Despite the enthusiasm from health system leaders, some need more convincing. The AARP, an advocacy organization for older adults, stresses that the programs should consider the burden of hospital-at-home on family members. “When you’re at home, things like changing and bathing do shift onto the caregiver,” says Megan O’Reilly a vice president in AARP’s government affairs unit. “These unpaid, informal family caregivers are increasingly taking on new tasks.”

And the Center for Economic and Policy Research notes that the government has not developed regulations for home hospitals equal to those that apply to regular hospitals. Its analysts question the reliance on telemedicine and remote monitoring, among other things.

With Medicare now throwing its weight behind home hospitalization, Montalto expects to see more definitive studies. But even then, hospital-at-home programs must win over patients, who have a choice between traditional and home treatment.

Many still balk at the unfamiliar choice. “Some days, we have so many patients who want to be transferred to us, some other days, no one,” Truong says. “We have a lot more work to do with convincing our patients that this is safe and effective.”

10.1146/knowable-012925-2

TAKE A DEEPER DIVE | Explore Related Scholarly Articles