Indigenous languages are founts of environmental knowledge

Peoples who live close to nature have a rich lore of plants, animals and landscapes embedded in their mother tongues — which may hold vital clues to protecting biodiversity

Support sound science and smart stories

Help us make scientific knowledge accessible to all

Donate today

Language, it is often said, is a window into the human mind. David Harrison experienced this firsthand as a young linguist in the 1990s when he traveled to the Russian republic of Tuva to spend a year with a group of herding nomads. During time with the Tuvans, he witnessed the close relationship between these Indigenous people and the animals, nature and landscapes they coexist with. That connection is deeply ingrained not only in Tuvan culture, but also in their language, from its rich vocabulary for describing their livestock and the world around them to its very sound, which can closely mimic noises of the landscape.

Harrison has since studied Indigenous languages in other parts of the world — from the Pacific islands of Vanuatu to the highlands of Vietnam — and learned that many of them are nature-centric in this way, reflecting millennia of deep observation of the natural world. Scholars increasingly recognize that many of these tongues encode much knowledge about the world’s species and ecosystems that is unknown to Western science — knowledge, Harrison argues, that may prove critical to protecting nature amid a global extinction crisis.

Harrison notes that the United Nations and other bodies have long acknowledged that Indigenous communities are usually better stewards of biodiversity than other people who are less attached to nature. “If we’re willing to be humble enough to learn from Indigenous people,” Harrison says, “what they know could help save the planet.”

Working with Indigenous communities to understand the environmental knowledge embedded in their languages is the goal of “environmental linguistics,” a line of research Harrison describes in a 2023 article in the Annual Review of Linguistics. This task is urgent, as many of the world’s thousands of Indigenous languages are threatened themselves, at risk of being replaced by more commonly spoken languages.

Harrison, who teaches at VinUniversity in Hanoi, Vietnam, spoke with Knowable Magazine about his studies of Tuvan language and what we can learn from nature-centric languages. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Generally speaking, what makes a language nature-centric?

Every language is connected to nature. But if the people who speak the language become distant from the natural world, that knowledge atrophies. In English, we used to use a lot of terms for animals that we don’t really use anymore. Now we just say “baby horse” because we don’t remember the difference between a filly and a colt. Tuvan — spoken by Siberian nomads — is especially nature-centric, though, because the majority of Tuvans still rely primarily on their animals and the landscape. They live in the middle of Siberia, one of the harshest environments on Earth, so it’s not a luxury or a hobby for them to be interested in nature; it’s a survival skill.

Tuvans also believe the landscape is sentient — that it has agency and exerts influence over their lives and their livestock. They make frequent offerings to the spirits, and build stone cairns — called ovaa — to appease the spirits that they believe reside in the landscape. They are careful to respect the landscape by not littering, by keeping seasonal campsites clean and by offering milk and food to certain consecrated sites. All of those things make their language nature-centric.

Tuvans, such as this family in Mongolia caring for their goats, have deep relationships with their livestock.

CREDIT: KELLY RICHARDSON

Tell me more about your time in Tuva. What surprised you about Tuvan culture and language?

Although Tuvans do have a writing system, they’re still a primarily oral society. I had my own bias around this. If you grow up in a literate society, you automatically believe that literacy is a superior state of human development, and people who are non-literate are deficient in some way. This gives us a considerable blind spot to the cognitive advantages of an oral society in its ability to transmit vast bodies of information without writing. It’s like weightlifting for the brain.

The Tuvan storyteller Šojdak-ool Xovalyg is literate in both Tuvan and Russian, but he relied purely on oral tradition when he memorized 10,000 lines of an epic heroine tale. It’s about a girl shamaness with magical shape-changing abilities, who sets off on a quest to bring her deceased brother back to life, guided by her wise talking horse. To complete the quest, she must win archery, footracing and wrestling contests. For those of us in literate societies, our abilities have so atrophied that that seems like magic. I personally am barely able to even memorize a telephone number. Tuvans have a lovely saying, ugaanga tönchü chok, which means “mind has no end.” They literally believe that the mind is infinite, and they demonstrate this through their memory capacity.

Every conversation we had turned to environmental concerns because that’s their life and livelihood. Tuvans are very attuned to the environment, constantly scanning the horizon and monitoring the weather and the sounds of their animals. Very subtle things that I might not notice are important to them. I could look at two goats, which both looked like brown goats to me. But to my host family, there was some subtle difference in the color or pattern that I couldn’t quite see, and that difference had a different label in their language.

If you have a label that allows you to single out individual goats from a herd of 200, that’s a survival technology. It was mind-expanding to learn that language can be connected to the environment in ways that I hadn’t really encountered before.

Is this nature-centric worldview only reflected in the vocabulary, or are there other ways in which Tuvan language encodes environmental knowledge?

It’s also built into the grammar. For example, the preferred way to say “go” in Tuvan refers to the direction of the current in the nearest river and your trajectory relative to the current. They keep track of that information as they’re moving around the landscape. When I once hosted a Tuvan friend in Manhattan, he asked me, “Where’s the river?” So I took him to the west side of Manhattan and showed him one of the rivers. And he took note of it, so he could use the Tuvan topographic verbs properly in New York City.

You can actually find environmental knowledge at every level of the language structure. For instance, Tuvans have a highly developed ability to mimic natural acoustics around them using their vocal tract. This is the basis for their world-famous art of throat singing. They’re passing on knowledge about the environment even at the level of sounds through their song.

By mimicking environmental sounds, they are in their view communicating with the spirits that inhabit the environment. But they also use this to induce favorable psychological states in their domestic animals under different scenarios. If a camel does not want to nurse her calf, they have a song that will help the camel attain a state where she will be willing to nurse her calf.

Tuvans, an Indigenous group of Siberian nomads, are well-known for their throat singing, an art through which they mimic environmental sounds.

CREDIT: MR HAPPY

What was it like to learn a nature-centric language like Tuvan? Did that change your views on our relationship with nature?

To be honest, I was initially not all that interested in the natural world. But if the majority of conversations happening around you are about the environment, you start caring about that. For example, Tuvans have a word, ий, pronounced “ee,” which means the short side of a hill. This is a very important concept, because you want to avoid the steep side of the hill if you’re walking, riding a horse, or herding your flock of goats. Once I learned the name for it, I began to look for it. But until the language provides you with this concept, you’re just oblivious to it. Learning these nature-centric concepts in the language makes you see the environment differently.

How does this nature-centric worldview shape people’s everyday lives in Tuva?

What Indigenous people have in their languages is a program for sustainability. Tuvans have limits and boundaries around the proper use of the environment — for instance, around how animals can be hunted or slaughtered, and when; which plants can be collected, when and where; to show respect for animals they hunt; as well as many conventions for how to treat domesticated animals. They believe in not taking more than what they need.

Such knowledge and behavioral norms are encoded in Tuvan language through verbs, nouns, phrases, aphorisms, songs and wise sayings. If a Tuvan says, “You should clean the sacred seasonal campsite,” that is kind of meaningless when translated into English, because we don’t have the concept of such a thing. But the Tuvan word for this, xonash, evokes a deeply emotional and sentimental response from Tuvan speakers, who are immediately aware of a whole range of beliefs and behaviors that follow from that concept. Sustainability is built into their language and worldview.

What have you learned from other Indigenous languages in terms of how they encode environmental knowledge?

They’re absolutely saturated with environmental knowledge. My recent work has been in the South Pacific island nation of Vanuatu, where I’m studying ecological calendars, which are linguistic systems used to track the time of year. They’re based on natural cycles, like the flowering or fruiting of certain plants, or the appearance of certain birds, insects or weather patterns. The Melanesians, who are Indigenous to Oceania, have been observing these patterns for so long that the patterns are completely reliable as a timekeeping method.

And here in Vietnam, I’m working with the Bahnar ethnic minority people. All of the manual arts that they produce — whether it’s basketry, architecture, canoes, textiles — are also environmental indicators. One particular basket I’m thinking of is made of four different plants, but one of those plants has become scarce recently due to deforestation and climate change, so they have to use plastic instead. So if you look at the basket, and the vocabulary used for talking about it, it’s telling a story about the current state of the environment.

The Bahnar people in Vietnam draw on their botanical knowledge and traditional skills to create intricate baskets, David Harrison explains.

CREDIT: EXPLORING CULTURES WITH PROF. DAVID HARRISON

What can we learn from the kind of environmental knowledge ingrained in Indigenous languages?

What Indigenous people know about their natural environments far surpasses what Western scientists know and is uniquely expressed in their languages. Most of the world’s plant species, for instance, have not yet been taxonomized within a Western scientific framework. But you talk to local people, and they tend to know all the plants and animals in their environment.

I remember meeting a man named Reuben Neriam in Vanuatu. I spent more than a week working with him and a team of botanists from the New York Botanical Garden, looking at photographs and specimens of plants. He was able to name more than 2,000 plants, which is astonishing. And he didn’t just name the plants, he talked about where and when they grow, when should they be harvested, how they’re processed, and what medicinal and nutritional properties they have. There’s this immense knowledge base that’s truly unappreciated and unknown to Western science.

How can this knowledge be used to help protect biodiversity?

To protect biodiversity, first we have to know how much biodiversity exists and where it exists. There are quite a few recent scientific papers debating this question of how you even measure biodiversity. Indigenous people are much closer than we are to knowing the richness of different species in their environments, how to use them for food or medicine and how they interact and behave.

For example, there’s a 2016 paper by David Fleck and Robert Voss that shows that many of the facts the Matses people of Amazonia know about armadillo behavior are unknown to Western scientists. This kind of knowledge can help us learn about biodiversity. We have to overcome our bias that Western science is superior to Indigenous ways of thinking.

Do you see any signs that Western science in general is beginning to recognize the environmental knowledge that Indigenous communities hold?

There are fields like ethnobotany, which is entirely devoted to Indigenous knowledge. Linguistics is moving in that direction, I would argue. But unfortunately, in some fields of science, there’s still this colonial, false discovery paradigm. For instance, in 2023 the World Wildlife Fund announced hundreds of new species discoveries here in Vietnam. What they didn’t do is ask local Indigenous people, “What do you call this animal?” Local people would have told them not only their name for the animal, but also stories and legends about it, why it’s important and what its lifecycle is.

But, you know, we can all get there. We just need to respect Indigenous people and treat them as our equals and teachers on biodiversity. And we’re at a critical juncture in history. We need to do it now before we lose the biodiversity that people used to know about.

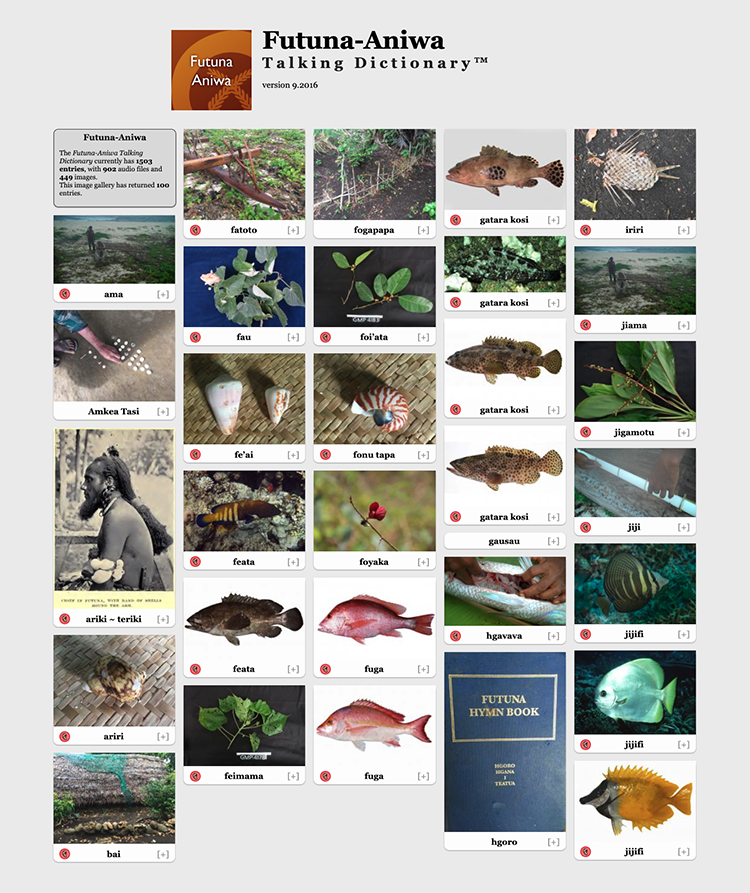

The Talking Dictionary database is a global repository of environmental knowledge from more than 200 languages, including Futuna-Aniwa, spoken in parts of Vanuatu.

CREDIT: DAVID HARRISON AND SWARTHMORE COLLEGE

Of the roughly 7,000 identified languages, nearly half are considered endangered. What can be done to preserve them and the cultural and environmental knowledge many of them contain?

Indigenous languages are under enormous pressure from global languages like English and Chinese, or from neglect or outright oppression of Indigenous communities. And the environmental knowledge they contain is not easily translated to other languages, so much of it would definitely be lost if the language stops being spoken, even if it were documented. So there’s a lot of different types of efforts underway, including documenting languages and revitalizing them.

I created an online platform called the Talking Dictionaries, which curates Indigenous knowledge about the environment through words, translations, audio recordings and photographs of species, and is hosted by Swarthmore College. For instance, the Talking Dictionary for Aneityum, spoken on the southernmost island of Vanuatu, contains a lot of Reuben’s botanical expertise. We’ve created more than 200 of those talking dictionaries, and they’re the intellectual property of the communities.

More recently, in my current job here in Vietnam, I’m helping to launch VinUniversity’s Center for Environmental Intelligence, which includes many different disciplines on environmentally sustainable development, including my anthropological research on environmental linguistics.

Crucially, it includes Indigenous experts as equal partners and custodians of knowledge about biodiversity. For instance, the Bahnar and other experts I am working with decide what knowledge they choose to record and share and are named as coauthors on the Bahnar Talking Dictionary and on peer-reviewed papers we publish. They are employed as paid expert consultants by my project and by the center, and we also provide them with training and technology so they can carry out independent projects.

By treating them as equals and not research subjects, we can elevate their culture and knowledge and contribute to their survival.

10.1146/knowable-012524-2

TAKE A DEEPER DIVE | Explore Related Scholarly Articles