The US immigration policy that has separated more than 5,400 children from their parents had spurred psychologists and pediatricians to warn that the young people face risks ranging from psychological distress and academic problems to long-lasting emotional damage. But this represents just a tiny part of a growing global crisis of parent-child separation.

Throughout the world, wars, natural disasters, institutionalization, child-trafficking, and historic rates of domestic and international migration are splitting up millions of families. For the children involved, the harm of separation is well-documented.

Hirokazu Yoshikawa, a developmental psychologist at New York University who codirects NYU’s Global TIES for Children, recently looked into research on the impacts of parent-child separation and the efficacy of programs meant to help heal the damage. Writing in the debut issue of the Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, he and colleagues Anne Bentley Waddoups and Kendra Strouf call for an increase in mental health training for teachers, medical doctors or other frontline service providers who can help fill the gap left by the lack of mental health providers available to cope with the many millions of children affected.

Knowable Magazine recently spoke with Yoshikawa about the crisis and what can be done about it. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Are there any good estimates of the number of children throughout the world who’ve been separated from their parents?

Exact numbers are hard to pin down, especially because several of the categories involved — like child soldiers and child-trafficking — aren’t well reported. What we know for sure is that the number of people around the world being displaced from their homes is at a historically high level. In 2018, some 70.8 million individuals were forcibly displaced due to armed conflicts, wars and disasters. That’s a record, and given that these phenomena often result in family separations and that more than half of these individuals were children under the age of 18, it suggests that historic numbers of children have been separated from their parents.

Why have such family separations become more common?

Many factors are driving it, but climate change is playing an increasing role in displacement and armed conflict all over the world. Climate change reduces access to dwindling resources and contributes to natural disasters, like floods, droughts, crop failures and famine. All of this increases conflicts, drives migration and breaks up families. This is not a blip in history; it’s a trend we will have to live with for generations to come.

What’s most important to know about the damage that comes from children being separated from their parents?

There are thousands of studies on the power of disruptions of children’s early attachments to their parents to cause longstanding problems. We’re talking about cognitive, social-emotional and other mental health impacts.

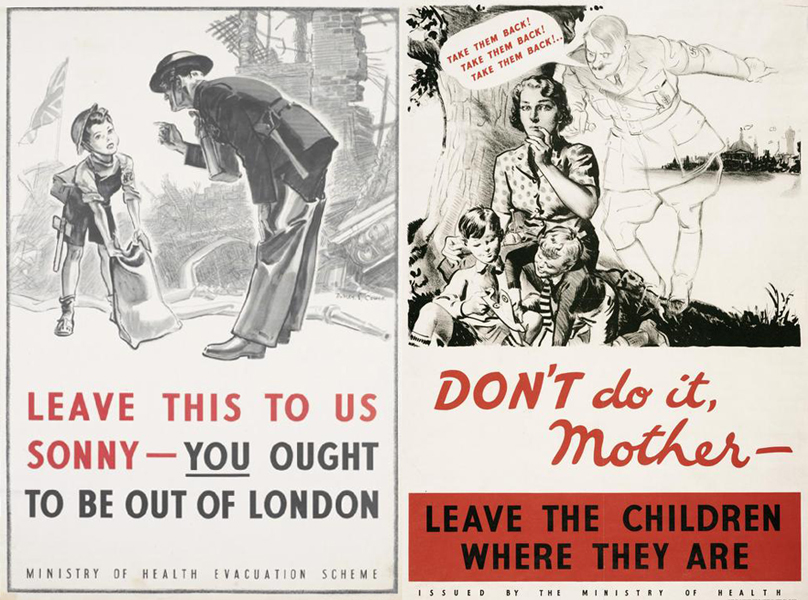

The developmental study of the mechanisms that may explain why these separations are so harmful goes back to before World War II, with the work of psychoanalysts and scholars such as Anna Freud, John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. In 1943, Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingame studied children who’d been evacuated from London and learned that in many cases being separated from their mothers was more traumatic for them than having been exposed to air raids. When families left London but stayed together, the children behaved more or less normally. But when children were separated from their mothers, they showed signs of severe trauma, such as wetting the bed and crying for long periods of time.

Later on, Bowlby and Ainsworth published their more well-known studies of how infants form attachments with their mothers, and how sensitive and responsive parenting is key to forming secure attachments both with parents and later on with others. Researchers have found that this process can be disrupted in prolonged separations — say of more than a week — before the age of 5.

Separating children from their parents can cause more than temporary stress. Research suggests it can affect children’s long-term well-being, academic success and ability to form relationships. Some of the seminal work on the psychological effects of family separation comes from studies of children evacuated from London during World War II in a government effort to protect them from bombing, as publicized by posters like these.

CREDIT: MINISTRY OF HEALTH / WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

More recently — for example, in the ongoing and high-profile studies of Romanian children who were raised in abysmally low-quality orphanages — researchers have shown how children in institutional care have suffered from poorer learning and social and emotional behavior due to the lack of intellectual and emotional stimulation and the opportunity to engage in relationships with caregivers.

How seriously children are affected can depend on factors such as whether the separation was voluntary or not, how long it lasts and what kind of care exists in its wake. Permanent loss of parents can create some of the most severe consequences, while long periods of parent-child separation, even if followed by reunification, can seriously disrupt a child’s emotional health. Children are generally more vulnerable to long-term harm to their social-emotional development in early childhood, up to five or six years, but no period of development is immune.

One major problem we see is that most children who are separated from their parents have already experienced some other trauma along the way, which then makes the separation even harder. When parents are present, they can often help buffer the impact of extreme adversity from bad experiences.

What did you learn that most surprised you as you reviewed the scientific literature?

The sheer range of outcomes was surprising to me — beyond learning and achievement and mental health outcomes, they include very basic human functions like impaired memory, auditory processing and planning. They also include a range of physiological outcomes related to stress that are themselves related to long-term disease and mortality. So parent-child separation as it is currently experienced can shorten lives and increase the chances of physical disease.

International migration — a major factor in separating children from parents — is at an all-time high, according to the United Nations.

Meanwhile, something that didn’t surprise me because I’m immersed in this literature all the time, but will probably surprise your readers, is that there are now about 8 million children in the world living in institutional care. This is a problem that reflects the lack of robust foster care and capacity of governments to facilitate placement with relatives, who will generally give more stable care than strangers. As we state in our review, even in otherwise good-quality institutional care, children suffer due to the high turnover of caregivers.

What relevance does your work have for US policies that have led to many parents and children being separated at the border?

US officials should know that there’s a global consensus, expressed in the UN Convention on the Rights of Children, on how to respond to children’s needs in this context. Primarily that means avoiding separating children from parents whenever possible and, when it must happen, keeping it as short as possible. An overwhelming amount of research, going back to Bowlby, supports these guidelines.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of research findings on children separated from their parents while awaiting detention. And it doesn’t make it any easier that the Department of Homeland Security has had so much trouble keeping track of the kids involved.

Yet there are hints of the kind of negative effects you might expect to see if you look at the research on children whose parents have been detained without warning, for example in large workplace raids to arrest undocumented workers. In these cases, researchers have found that children have missed school and suffered behavior problems and depressive symptoms.

This brings up the fact that, in the United States, we’re talking about many more than 5,000 children being separated from parents. While the separations at the Mexican border have gotten a lot of media attention, millions of other children across our country are affected by the relatively recent harsher, sweeping policies resulting in more detentions and deportations of immigrants already living in the US. This has created a climate in which the threat of family separation is omnipresent.

We’re particularly concerned that many children separated from their parents stop going to school, perhaps from lack of supervision or from the need to support themselves or family members. The humanitarian sector tends to focus on basic needs and that’s understandable — they want to save lives. But from a developmental perspective, we have to focus on whether children thrive, not just survive.

Unaccompanied children who are trying to migrate are an increasing part of this global problem. What kind of special risks do they face?

It’s true that there has been a significant increase in recent years in unaccompanied minors trying to migrate internationally. At the US border, this increase has been happening since the 1990s, due to both economic crises and increases in urban violence in Mexico and in Central American countries. But the trend is now accelerating. From 2015 to 2016, there were five times as many children estimated to be migrating alone than from 2010 to 2011. In 2017, more than 90 percent of undocumented children arriving in Italy were unaccompanied.

While the overall number of children migrating to Europe fell in 2017 (compared with 2016), the proportion arriving without a parent or guardian rose to 60 percent. The vast majority of these unaccompanied children are teens, arriving in Italy, Greece, Spain and Bulgaria, having journeyed from Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Gambia, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Algeria, Morocco and elsewhere.

Compared with refugee children who flee with their families, unaccompanied children are at greater risk for trauma and mental illness. One study of refugee children attending a clinic in the Netherlands found that the unaccompanied children were significantly more likely than those traveling with their families to have been victim to four or more traumatic events in their lives, including during their travels. They also had a higher rate of depressive symptoms and even of psychosis than refugee children living with their families.

What are some of the best ways that governments and nonprofit organizations can help these children?

Whatever can be done to avoid the separation from parents in the first place and to avoid detention and institutionalization of children whenever possible is in the children’s best interests. (That’s the guidance from the Global Compact for Refugees, Article 9 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and other global rights documents.) After that, it’s a matter of limiting the time away from parents or other caring adults as much as possible. The earlier and younger that children leave institutional care for stable foster care or adoption, the better it is for them.

You can see this in some of the follow-ups of the study of children in Romanian orphanages. Children who left the orphanages for foster care by 15 months of age had trouble speaking and understanding in early childhood, but not later. Children placed before 30 months showed growth in learning and memory so as to be indistinguishable from other children by age 16. So recovery from early institutionalization is possible, but it may take longer if a child spent more time in the orphanage.

What kinds of programs for children, if any, can help lessen the impacts of being separated from their parents?

In general, programs that help equip children for their daily lives can be useful. That includes education in decision-making, problem-solving, communication and stress management.

Teachers and doctors can play a major role, at minimum by identifying children who need mental health services and directing them to programs. The fact is we’ll never have enough mental health providers, so it makes sense to train members of the education and basic health systems that are already in place.

In the review, we describe a few of these efforts. One that stood out for us took place in two schools in London where children on average aged 12 to 13 had been separated from one or both parents due to war or migration. They came from Kosovo, Sierra Leone, Turkey, Afghanistan and Somalia. Teachers identified children who needed services, and who then spent one hour a week for six weeks with a clinical psychology trainee doing cognitive behavioral therapy. The treatment helped reduce PTSD symptoms, and the children’s teachers later reported that the children were behaving better in the classroom.

Granted, this was a very small study with no longer-term follow-up, so you can’t draw very strong conclusions, but it hints that even such a short-term intervention can be helpful in addressing children’s traumas. Studies have shown that even as few as 12 sessions of counseling from people trained in cognitive behavioral principles can help many people.

Family separation can cause problems for children of all ages but can be particularly traumatic for younger children. In 2017, most children migrating to Europe without a parent were young adults (aged 15 to 17), but a substantial portion (23 percent in Bulgaria and 17 percent in Greece) of arrivals were 14 or under.

Do we have any idea of how many kids are being helped by these sorts of interventions? Are we still mostly talking about small experiments?

We’re not anywhere close to meeting the need for services. Unfortunately, health systems worldwide continue to overlook all kinds of mental health needs, particularly in low-income countries, even as depression and other mental illnesses take an economic toll, leading to reduced lifespans and reduced economic activity. The economic costs of mental health problems are huge, yet this may be one of the most underinvested areas in terms of health care.

The largest program you describe is in China, which isn’t that surprising, given how many internal immigrants China has.

Yes, there are potentially tens of millions of Chinese children and youth whose parents travel to cities to work and leave them behind, in the care of grandparents or other relatives. Between one-third and 40 percent of children in rural areas of China are in this situation. And there’s a lot of research documenting that these children are doing less well than children who are being raised by parents.

We describe one community-based program involving 213 rural villages with nearly 1,200 left-behind children. For three years, each village designated a space for after-school activities for the youth and hired a full-time employee to provide welfare services. The findings suggest the approach helped reduce disparities between the left-behind and non-left-behind groups.

What if anything gives you hope that this situation may improve?

The outcry over the US policies has increased awareness about a very vulnerable population of children. That could be a silver lining of the crisis. These parent-child separations are going on not only at the border, but also all over the country. The hope is that the attention will increase support for organizations, such as the national Protecting Immigrant Families Coalition, that are working to make a difference.

When it comes to children throughout the world who’ve been separated from their parents, we need a lot more people to be aware and concerned so as to provide the attention, stimulation and care that can help them recover.

Editor's note: This article was updated on January 24, 2020, to clarify that in addition to teachers and medical doctors, Dr. Yoshikawa and his colleagues also recommend mental health training for all frontline service providers.