Shared mobility: Making travel easier for all

Carshares, bikeshares and the like are a positive for the environment, though access to them isn’t equal. What can be done to give everyone more transportation options?

Support sound science and smart stories

Help us make scientific knowledge accessible to all

Donate today

Walk around most large metropolitan cities in Europe and the United States, and you’d be forgiven for thinking that we’re living in a brave new world of affordable and effortless mobility for all, with the smartphone in your pocket a portal to a cornucopia of shared e-scooters, bikes and electric cars, and an Uber or Lyft never more than five minutes away.

But if you’re disabled or elderly, living in a low-income area or — imagine! — without a smartphone or credit card, using these shared mobility services becomes a lot more difficult. They tend to cluster in more affluent urban areas, and are often inaccessible to people with reduced mobility or those traveling with young children needing child seats. In part because of these factors, users are disproportionately younger, wealthier, able-bodied, white and male.

Shared mobility could be a key part of a more sustainable transportation system. But to be most effective, it needs to include everyone. For-profit shared mobility providers have largely failed to deliver on this, but various initiatives and projects are finding creative solutions to reach underserved communities.

The potential benefits are large. On-demand shared mobility that feeds into well-developed public transportation systems could reduce the number of vehicles in some cities by 90 percent and cut transportation emissions by 50 percent — but only if it largely replaces private car use. “The car has to be a guest, not the main actor,” says Luis Martinez, lead modeler at the International Transport Forum, who coauthored a paper on shared mobility and sustainability in the 2024 Annual Review of Environment and Resources.

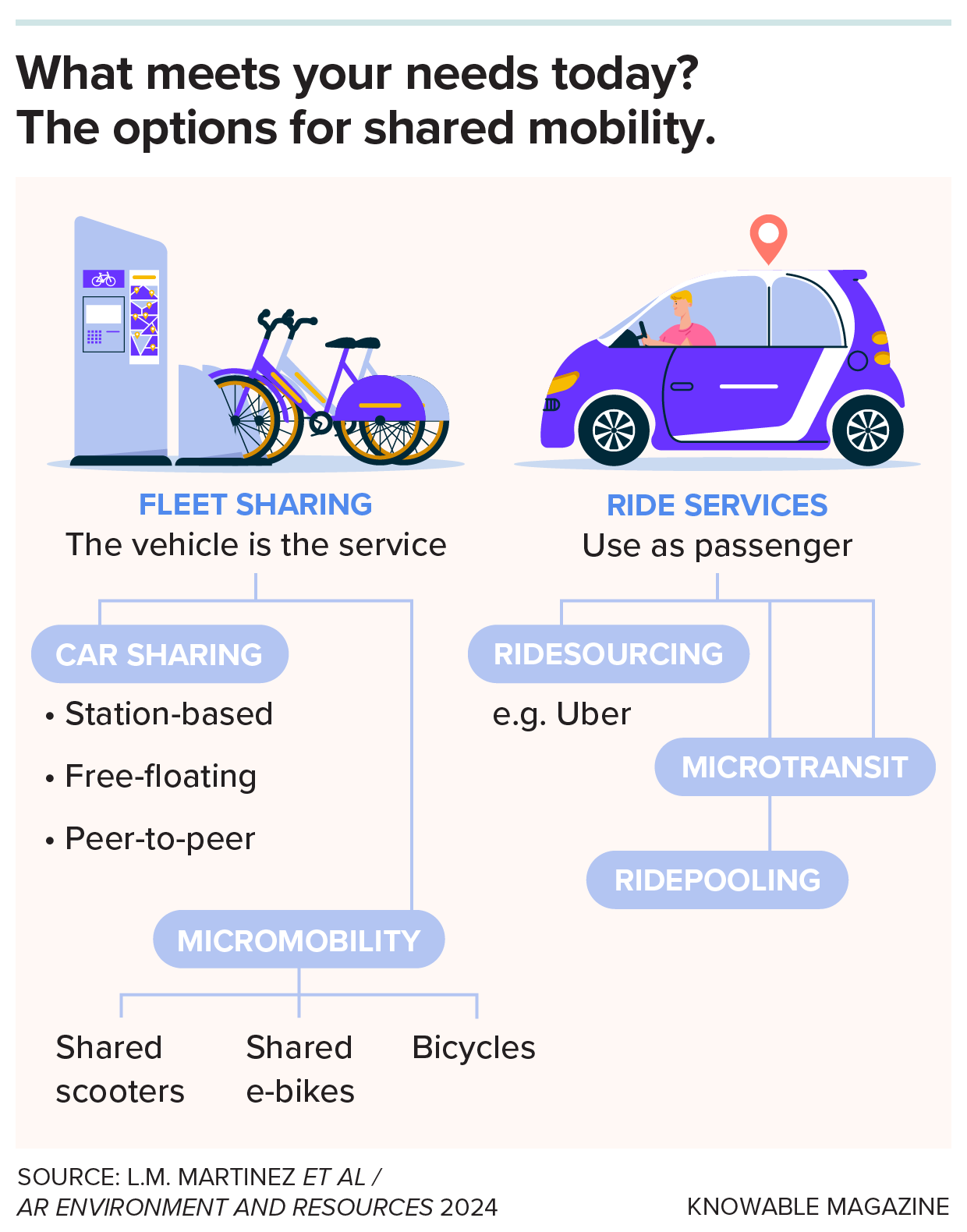

Today’s on-demand shared mobility includes a variety of vehicles and service models.

Achieving that goal will be challenging, especially in the Global North, where people choose private cars for 61 percent of the kilometers they travel. To move more people away from private vehicles to shared ones, expanding access to a wider share of the population is an important first step, researchers say, because a lot of people are left out today.

A 2019 study of 10 US cities, for example, showed that white Americans have access to almost three times as many carshare locations and two times as many bikeshare locations within a half-mile radius as African Americans. When hailing rides from their home, African Americans also wait up to 22 percent longer for the ride to arrive.

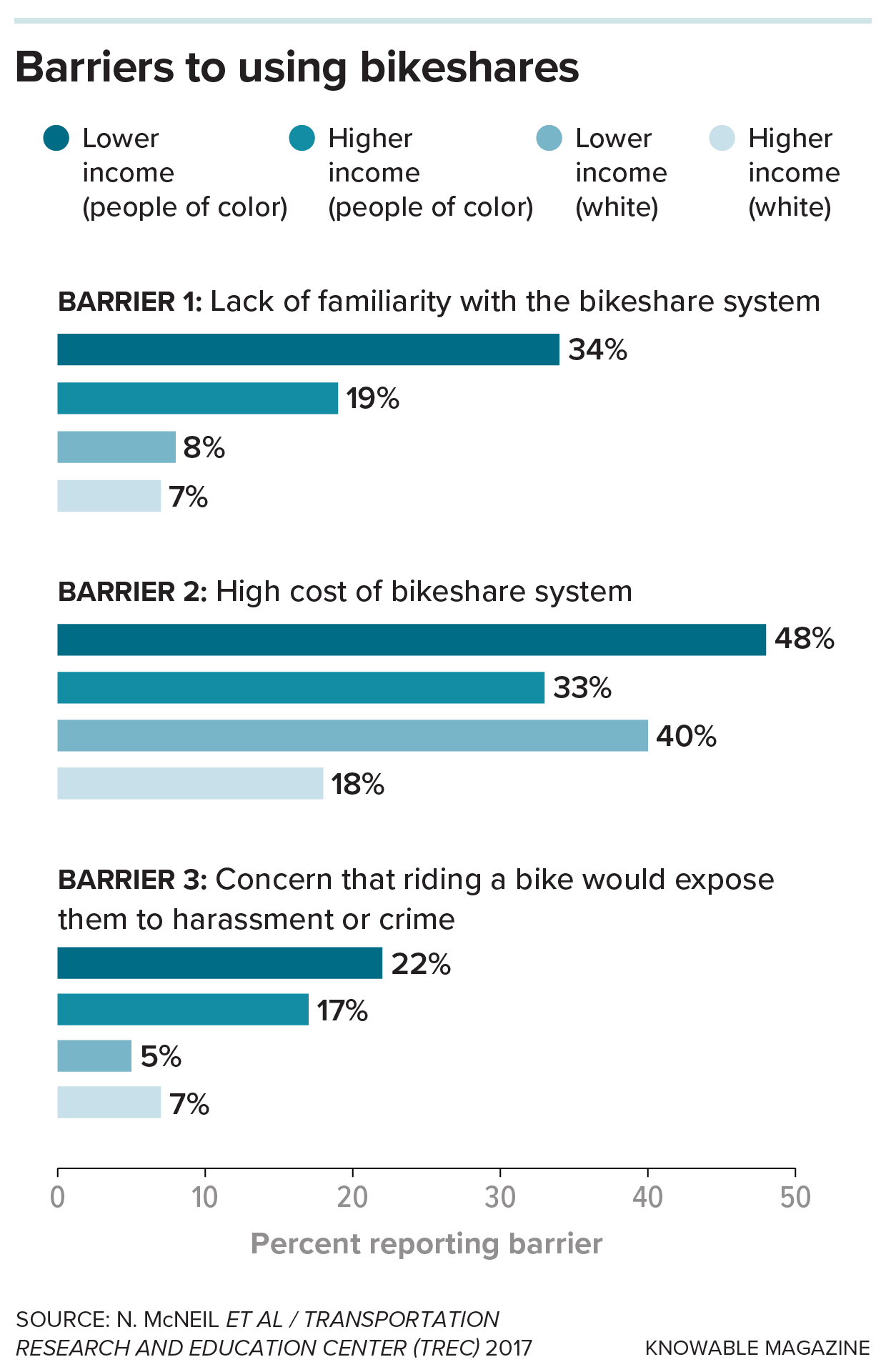

But even when efforts are made to expand services to underserved areas of a city, other hurdles persist. A fifth of low-income Americans still don’t have a smartphone and almost a quarter don’t have a bank account — both prerequisites for using most such services. A 2017 survey in Philadelphia, Chicago and Brooklyn showed that low-income people of color are just as interested in bikesharing as other groups, but less likely to use such a system: While 10 percent of higher-income white residents and five percent of higher-income residents of color were members of a bikeshare system, only two percent of lower-income residents were.

Forty-eight percent of lower-income residents of color cited cost as a big barrier. In addition, lack of familiarity with the bikeshare system was holding a third of people back.

How to bridge the accessibility gap? A fundamental problem, Martinez says, is that “private businesses will always go where the money is.” Unsurprisingly, then, public agencies are the ones stepping in. A handful of cities in the United States, for example, have launched subsidy programs for low-income residents, which have shown promise in increasing the use of shared mobility while decreasing the use of personal vehicles. In 2024, a survey of almost 250 bike- and e-scooter-share programs in the US found that 70 percent had taken steps to reach underserved groups, with measures like cash payment and non-smartphone options being among the most popular.

People of color, especially those with lower incomes, face a number of barriers to using bikeshares, according to a 2017 survey in Philadelphia, Chicago and Brooklyn.

Nongovernmental organizations are also filling the gap. One example is a program by nonprofit Shared Mobility Inc. in Buffalo, New York. In the summer of 2020, it suddenly found itself in possession of 3,000 electric bikes, part of the fleet Uber scrapped when selling the bikesharing arm of its business earlier that year.

“The E-Bike Library model was born from that,” explains Shane Paul, who oversees the initiative, helping community-based organizations set up e-bike libraries for underserved populations. At their first location in a transit desert on Buffalo’s East Side, 71 percent of members were first-time e-bike riders and 84 percent identified as people of color.

Shared e-bikes are a particularly promising substitute for cars in urban areas, with one report estimating that a shift to e-bikes could take 8 million cars off US roads. E-bike libraries address a number of barriers: The bikes are free, and the libraries are hosted by places that are already an important part of the community. In addition to maintaining the bikes, the programs also organize training, group rides and educational events to familiarize people with cycling culture and safety.

“It can be something as simple as making sure you lock your bike,” says Paul. "These types of programs create a space for people to learn these skills.”

The nonprofit Shared Mobility Inc. in Buffalo, New York, is helping community-based organizations across western New York set up e-bike libraries for underserved populations. In addition to providing the e-bikes free of charge, the libraries also organize group rides and educational events to familiarize people with cycling culture and safety.

CREDIT: PAT CRAY

Personal interactions and affordability are also important for Mobitwin, a social transportation service for elderly people and those with reduced mobility. Founded by the Belgian mobility nongovernmental organization Mpact, it lets elderly people request a ride from a volunteer for a nominal fee. The program, which has been running since the 1980s, currently serves around 40,000 people in Belgium.

Being able to get out and about is a crucial part of participating in society, and reduced mobility in old age goes hand in hand with social isolation and loneliness, says Esen Köse, project manager at Mpact. “We want to make sure that people who are often not in the societal cycle of going to work or going to school, who are actually often left out, that they still have an option to get out of the house and do the simple daily things, like going to the grocery store, going to the hairdresser, seeing families.”

The booking process still primarily operates through a phone call — a recent attempt to switch to an app proved ill-suited to older users and was never implemented. A lack of digital literacy was one problem, but members also don’t want to give up the social connection that comes from calling up an operator and requesting a ride, says Köse. Devising programs that work isn’t just about the latest technology or trends in shared mobility options, she adds. “It’s really starting from, ‘OK, what are the needs of the people?’”

Tim, a carsharing service run by the Austrian city of Graz, also maintains an email- and phone-based booking system in addition to its app. “Senior citizens are often also good with phones,” says Katharina Mayer, head of the service. “But some are not, so we offer the necessary support.”

The service has also recently added a wheelchair-friendly vehicle to the fleet, and it is focused on optimizing the service for women. In 2024, only 39 percent of tim's carsharing users were women, and customer satisfaction surveys showed that a lack of car seats for children was one of the reasons. This led tim to include booster seats in all its cars, with seats for younger children available upon request free of charge. A survey planned for later this year will measure the impact of this change, but already, Mayer says, new customers call to inquire whether child seats are available.

The mobility patterns of women also differ from those of men, in part because women tend to combine multiple short trips into one journey, for example to buy groceries and pick up children on the way home from work. “That makes their mobility a lot more complex,” says Lina Mosshammer, founder and CEO of the Austrian mobility consulting company Point&. Since shared mobility solutions are usually priced by duration, distance or both, trip-chaining makes them more expensive, and most services aren’t designed with small children in mind.

Small tweaks like adapting the handle design on e-scooters for women’s hands, which are often smaller, and offering family accounts or cheaper fares for breaks in travel can help to accommodate caregivers’ needs, says Mosshammer. Free helmets and SOS buttons on bikes and e-scooters could also help address their concerns for personal safety. When mobility companies have more women in management and other positions, they also tend to have more women as users, she adds. “You tend to plan for what you know. That’s why it’s so important to bring in different perspectives in the development of mobility.”

Station-based systems — where cars are picked up and dropped off at fixed locations such as train stations, rather than left on the street as is the case with free-floating systems — can also make it easier for women to plan for their complex transportation needs. “Let’s say you have to bring your kid to violin lessons every Thursday. You can book a car for every Thursday between 2 p.m. and 4 p.m. a month in advance, and you know the car will be there,” says Mayer.

There is another reason that the city of Graz opted for this model: A free-floating system competes with public transport, while a station-based one complements it. “Our big goal is for people in Graz to sell their cars,” says Mayer. “Our vehicles must offer enough options to facilitate this shift.”

10.1146/knowable-041425-1

TAKE A DEEPER DIVE | Explore Related Scholarly Articles