Your cells are dying. All the time.

Some go gently into the night. Others die less prettily in freak accidents or deadly invasions, or after a showy display.

Support sound science and smart stories

Help us make scientific knowledge accessible to all

Donate today

Billions of cells die in your body every day. Some go out with a bang, others with a whimper.

They can die by accident if they’re injured or infected. Alternatively, should they outlive their natural lifespan or start to fail, they can carefully arrange for a desirable demise, with their remains neatly tidied away.

Originally, scientists thought those were the only two ways an animal cell could die, by accident or by that neat-and-tidy version. But over the past couple of decades, researchers have racked up many more novel cellular death scenarios, some specific to certain cell types or situations. Understanding this panoply of death modes could help scientists save good cells and kill bad ones, leading to treatments for infections, autoimmune diseases and cancer.

“There’s lots and lots of different flavors here,” says Michael Overholtzer, a cell biologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. He estimates that there are now more than 20 different names to describe cell death varieties.

Here, Knowable Magazine profiles a handful of classic and new modes by which cells kick the bucket.

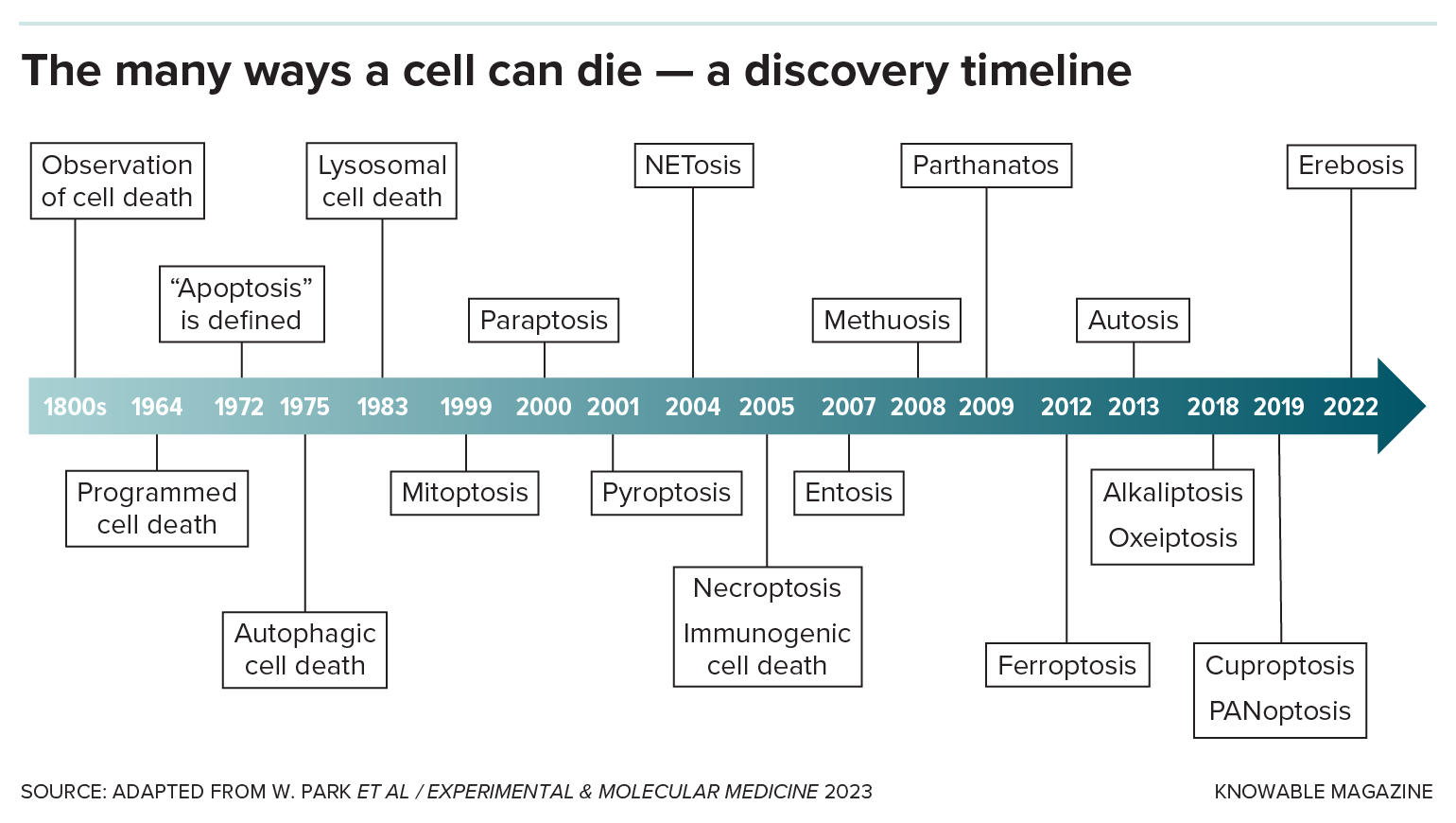

The identification of new forms of cell death has sped up in recent years.

Unplanned cell death: Necrosis

Lots of bad things can happen to cells: They get injured or burned, poisoned or starved of oxygen, infected by microbes or otherwise diseased. When a cell dies by accident, it’s called necrosis.

There are several necrosis types, none of them pretty: In the case of gangrene, when cells are starved for blood, cells rot away. In other instances, dying cells liquefy, sometimes turning into yellow goop. Lung cells damaged by tuberculosis turn smushy and white — the technical name for this type, “caseous” necrosis, literally means “cheese-like.”

Any form of death other than necrosis is considered “programmed,” meaning it’s carried out intentionally by the cell because it’s damaged or has outlived its usefulness.

A good, clean death: Apoptosis

The two main categories of programmed cell death are “silent and violent,” says Thirumala-Devi Kanneganti, an immunologist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. Apoptosis, first named in 1972, is the original silent type: It’s a neat, clean form of cell death that doesn’t wake the immune system.

That’s handy when cells are damaged or have served out their purpose. Apoptosis allows tadpoles to discard tail cells when they become frogs, for example, or human embryos to dispose of the webbing between developing fingers.

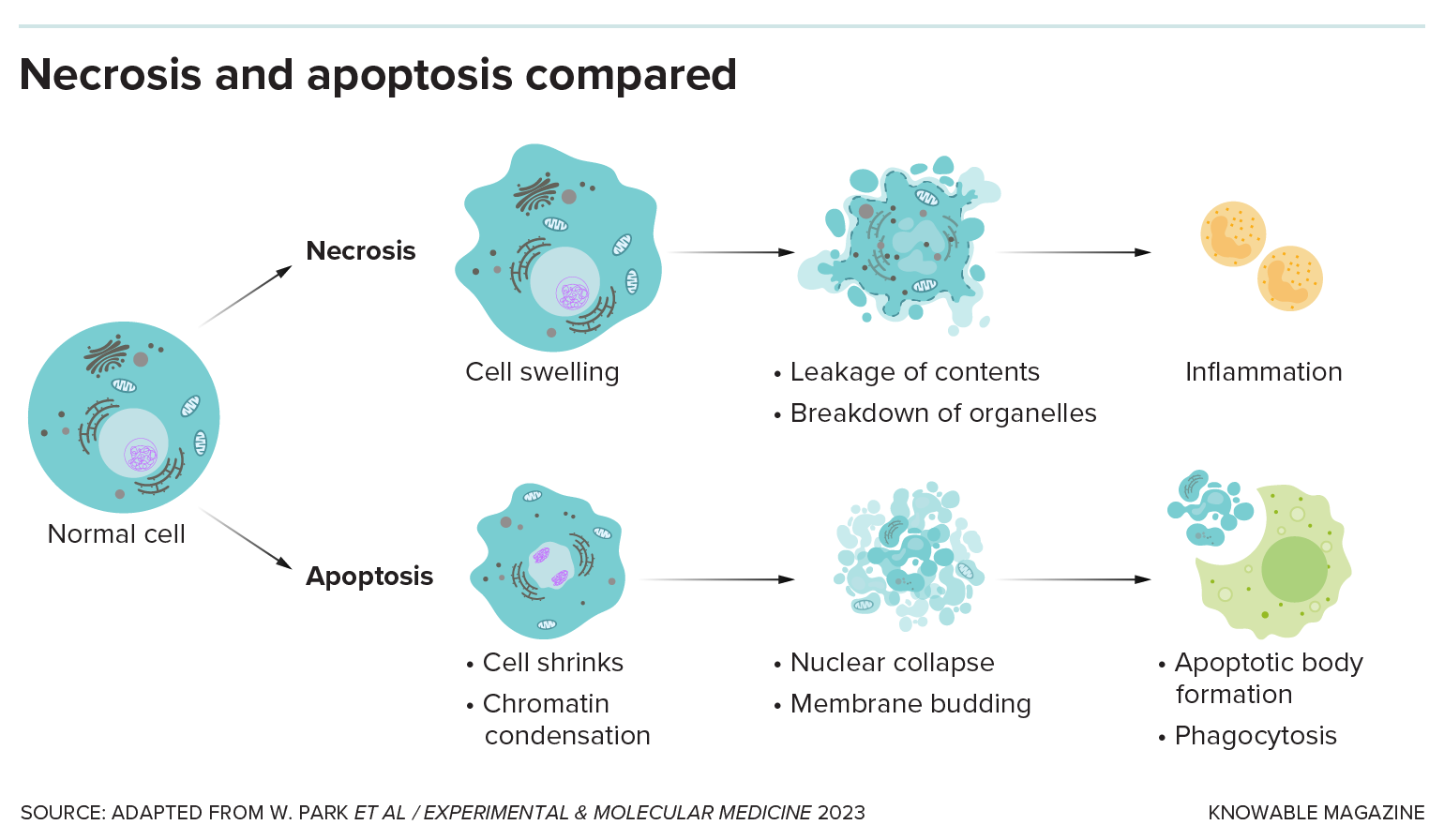

The cell shrinks and detaches from its neighbors. Genetic material in the nucleus breaks into pieces that scrunch together, and the nucleus itself fragments. The membrane bubbles and blisters, and the cell disintegrates. Other cells gobble up the bits, keeping the tissue tidy.

In necrosis, a cell dies by accident, releasing its contents and drawing immune cells to the site of damage by creating inflammation. In apoptosis, the cell collapses in on itself and the bits are cleared away without causing damaging inflammation.

Red flags: Necroptosis and pyroptosis

These are the violent kinds, and they helped expand the cell death repertoire beyond apoptosis and necrosis. They’re often engaged when cells have been hijacked by viruses or other infectious agents. Rather than be reduced to virus factories, they kill themselves. These cells go down waving big red flags, in the form of chemicals they release to alert the immune system to come in and save their neighbors.

In a 1998 study, a team disabled the ability of cells grown in dishes to undergo apoptosis, and the cells still died. But they did it in a messy way that came to be called necroptosis for its mix of apoptosis and necrosis features. As with necrosis, the cells and their organelles swell up and then the outer membrane ruptures. Necroptosis is a handy backup mechanism because some infectious agents can disable apoptosis.

Then there’s pyroptosis, first observed in 1992 among white blood cells infected with dysentery bacteria and christened in 2001. This is “the screaming, alarm-ringing pro-inflammatory death of a potentially dangerous cell,” the namers wrote. As with necroptosis, cells swell up. They activate enzymes that poke holes in the cell membrane, so their contents leak out, calling up an immune response.

Whether from pyroptosis or necroptosis, that immune response is needed to activate the body’s defenses against infection, such as the fever that cooks invaders, says Kanneganti, who coauthored an article about molecules involved in cell death in the 2020 Annual Review of Immunology. But if too many cells die or the immune system gets stuck in the “on” position, that can lead to ongoing inflammation or autoimmune disease.

Mix and match: PANoptosis

Immune cells, too, may need to die in the case of infection, inflammation or even cancer. As Kanneganti’s group investigated this process, they noticed an alternate mode of death that incorporated elements of apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis. Using the first letter of each classic type, they dubbed it PANoptosis. Since then, researchers have found this hybrid death method in other kinds of cells, too.

In PANoptosis, the cell assembles a big protein machine called the PANoptosome. This activates enzymes to puncture the cell’s membranes. As it dies, the cell releases red-flag molecules that tell other immune cells there’s a problem.

Why do cells need so many ways to achieve the same fatal end? Cells probably evolved these different options during an arms race with disease-causing microbes, Kanneganti surmises. The microbes, aiming to survive, may try to turn off cell death. But if the cell has a wide menu of death mechanisms, it can commit suicide in another manner, sacrificing itself to thwart the pathogen.

Kamikaze killing: NETosis

Immune cells may sacrifice themselves even more dramatically, in a kamikaze action that takes out surrounding pathogens too. This sensational act is the purview of white blood cells called neutrophils, which patrol areas of infection and swallow invaders.

But sometimes the infectious agents are too large, or too numerous, to devour. The neutrophils switch tactics and vomit their own DNA over the pathogen, ensnaring the invaders in a kind of genomic net. It’s called NETosis (for neutrophil extracellular traps). Other cells then dispose of the entangled pathogens.

On occasion, the net-throwing cell is already dying or dead as this takes place, making it a zombie cell committing one final, altruistic act, says immunologist Ben Croker, who studies the phenomenon at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine.

Death metal: Cuproptosis and ferroptosis

While cancer cells seem ominous, they are, in fact, quite vulnerable to death, says Todd Golub, a cancer biologist at the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “The key,” he adds, “is to find the right triggers.”

Golub’s group found a trigger in drugs that ferry copper into cells. The team is still working out how that makes the cells croak in a process they christened cuproptosis in 2022.

Iron, too, can be deadly to cancer cells, as chemical biologist Brent Stockwell at Columbia University in New York discovered. In addition to tumors, normal cells in the brain, liver and kidneys appear to be particularly susceptible to this form of cell death, which he named ferroptosis in 2012. Researchers have also observed ferroptosis in a wide range of organisms, even yeast and plants, says Stockwell, who cowrote a description of the key features of ferroptosis in the 2019 Annual Review of Cancer Biology.

Stockwell and other researchers are working to identify drugs or special diets that would activate ferroptosis to combat cancer, or block it to protect cells from dying in diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

Eat me: Entosis

Overholtzer, while studying breast cancer cells in the early 2000s, noticed something weird: cancer cells burrowing into other cells. He and his lab supervisor dubbed the phenomenon entosis in 2007.

The invading cell winds up enclosed in a big, membranous bubble. It may starve and undergo apoptosis, or be killed by the surrounding cell. Then the outer cell digests its remains.

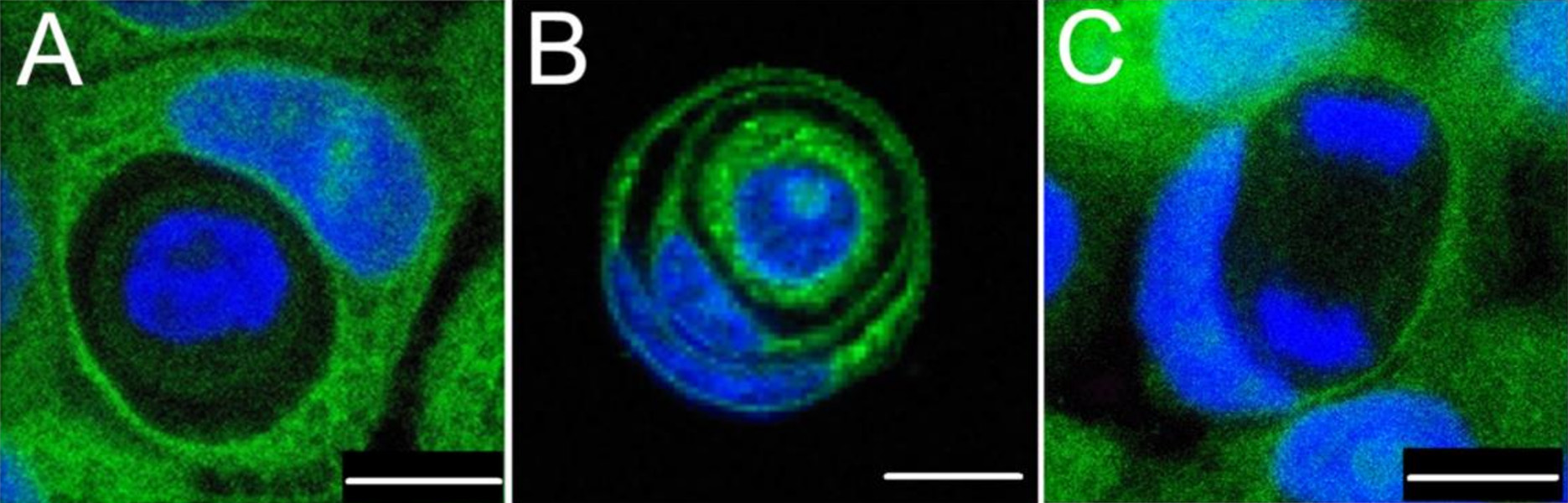

During entosis, one cell inserts itself within another. In these images, blue indicates cellular DNA and green indicates the cytoplasm, a cell’s gelatinous interior. One cell may exist within another cell (A); a cell may exist within a cell within yet another cell (B); and an inner cell may undergo DNA division (C).

CREDIT: I. MLYNARCZUK-BIALY ET AL / CANCERS 2020

But sometimes, weirdly, it survives and pops out of the cell to live independently again. Noting this, some researchers have proposed that entosis gives cancer cells a way to temporarily hide out from the immune system or cancer drugs.

There’s still plenty to learn about cell deaths, and there are probably death modes still awaiting discovery, Golub speculates.

Ultimately, the study of life requires the investigation of cell death. As the Japanese author Haruki Murakami wrote, “Death exists, not as the opposite but as a part of life.”

Editor’s note: On September 24, 2024, the graphic titled “The many ways a cell can die — a discovery timeline” was updated to add PANoptosis, a type of cell death that had been omitted in the earlier version.

10.1146/knowable-092324-1

TAKE A DEEPER DIVE | Explore Related Scholarly Articles